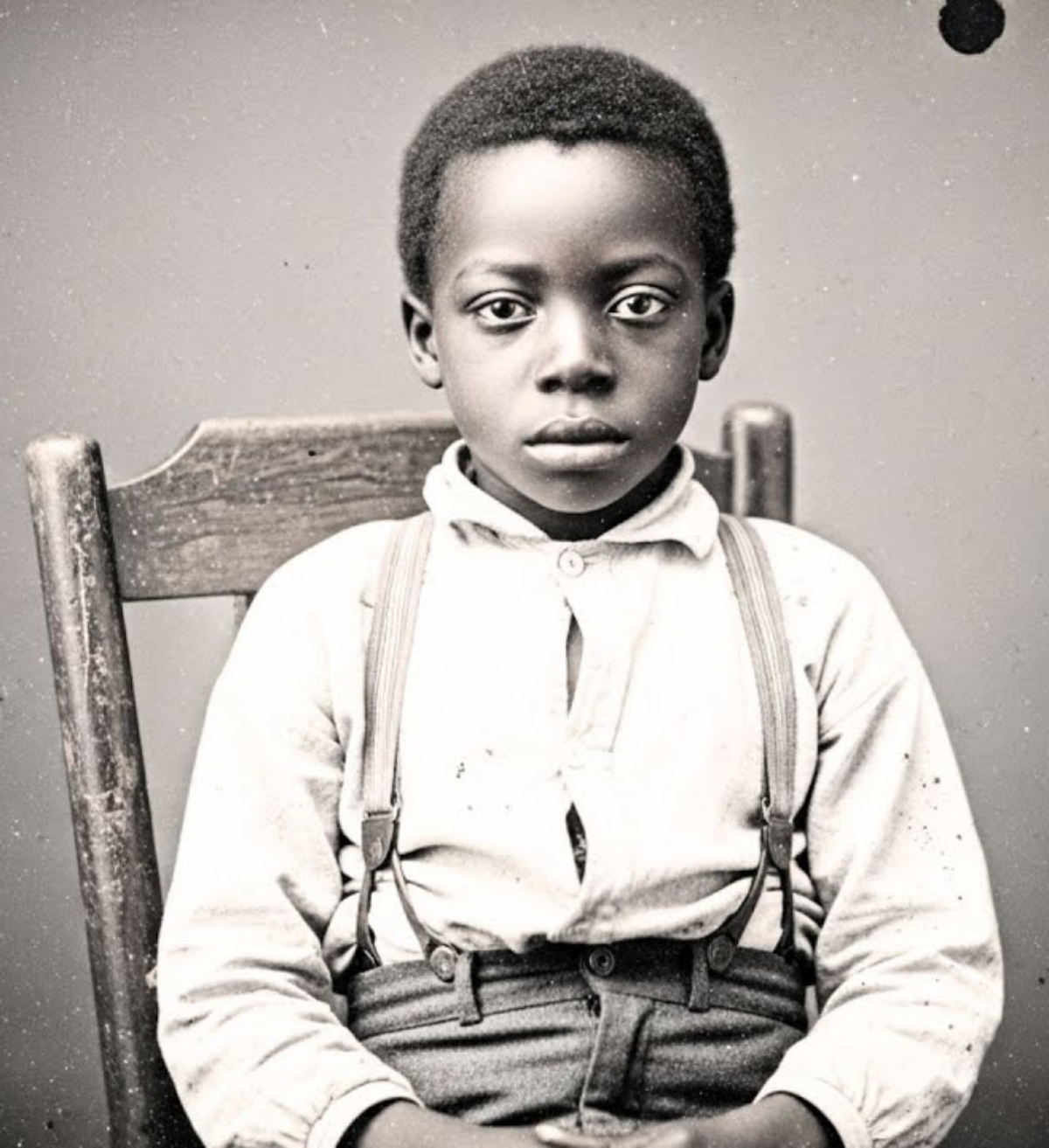

In the suffocating autumn of 1859, in the isolated village of Meow Creek, Louisiana, a seven-year-old Black boy named Samuel Carter became the center of one of the most bewildering and terrifying medical cases documented in the American South before the Civil War. Dr. Elizabeth Monroe, the only formally trained physician in a region dominated by folk healers and midwives, filled two leatherbound journals with observations. The child’s capabilities defied every known law of human nature. At first glance he seemed ordinary—small, frail, dark eyes that rarely blinked, skin like rich Mississippi soil. Yet behind that appearance dwelled an intelligence science could not classify or comprehend.

Over seven terrifying months, nine people died under inexplicable circumstances after interacting with Samuel. All were found with eyes wide open, as if they had witnessed something beyond comprehension. The boy claimed to hear voices from the swamp—whispers of secrets, hidden truths, and imminent deaths. He knew precise anatomical details, predicted diseases before symptoms, and spoke of intimate dreams no one had shared. His existence challenged what white society believed, and his fate reflected the silencing of brilliant Black minds deemed too extraordinary to be allowed.

Official records were partially destroyed during the Civil War, but Dr. Monroe’s journals survived—hidden in her attic for over a century. They reveal a story that challenges the limits of the human mind and raises disturbing questions about abilities science still cannot explain. This is a story of a Black child whose gifts terrified white society and threatened a system built on claims of Black inferiority. It is a reminder of the cost of brilliance in a world intent on erasing it.

Samuel Carter was born in spring 1852 on the Whitmore plantation, a large cotton operation in Ascension Parish. His mother, Esther, a house servant, learned to read despite laws forbidding literacy among enslaved people. She traced letters in the dirt behind the kitchen house, teaching Samuel in whispers and stolen moments. His father’s name never appeared in records; he was sold before Samuel’s second birthday. Esther would sometimes sit by the window crying, staring into the darkness beyond the quarters.

At four, Esther developed a persistent cough. Plantation owner Robert Whitmore refused to call a doctor, forcing her to continue working as she deteriorated. Samuel sat beside her at night, clutching her hand, and spoke words that frightened her—of sickness blooming like a flower with roots spreading through her chest, and voices in the swamp warning she would die before cotton bloomed again. Esther died three months later in February 1856, coughing blood into rags Samuel tried to keep clean. He did not cry at the funeral.

He stood still while spirituals rose over the unmarked graves reserved for enslaved people. When asked why he didn’t weep, Samuel said, “She’s still here. She talks to me now like the others in the swamp. She says she’s finally free.” Fear spread among the enslaved community. Something in his eyes felt old and knowing—unsettling in a child. Old Jeremiah said Samuel was born with a caul, able to see both the living and the dead.

“The boy got the sight,” Jeremiah warned. “He knows things not meant for the living.” Robert Whitmore noticed Samuel’s strangeness, too, but his fear took another form. The boy was too smart, observant, and articulate for an uneducated slave child. At five, Whitmore caught him drawing in the dirt—detailed anatomical sketches of a human heart with labeled parts in careful script. “Where did you learn to write?” Whitmore demanded.

“The voices teach me,” Samuel replied. “They show me things I draw in the dirt. The body is just a house, and when the house breaks, the person inside has to leave.” The idea that a Black child could possess superior knowledge and intelligence terrified Whitmore. Samuel’s existence challenged the foundation of racial hierarchy—proof that claims of Black inferiority were a lie. In summer 1856, Whitmore sold Samuel to a trader passing through the parish.

Samuel was separated from his community and sent north along the Mississippi River. The trader, Cyrus Blackwood, saw profit in the boy’s intelligence and strangeness—thinking wealthy families or medical institutions would pay for such a curiosity. But Samuel never reached auction. During a stop in Meow Creek, Blackwood fell violently ill—convulsing, bleeding from nose and ears, dying within hours. Samuel watched calmly from a corner.

“He hurt children,” Samuel said when authorities questioned him. “The voices told me. They said his time was finished.” Investigations revealed a pattern: enslaved children in Blackwood’s custody had died or disappeared under suspicious circumstances. With no guardian and no papers, Samuel was technically free—though such freedom meant little for a Black child in Louisiana. Orphanages refused him; local families avoided him; he was too young to work and too strange to ignore.

Dr. Elizabeth Monroe took Samuel in. A woman trained in Philadelphia, she practiced medicine in the South despite stigma and barriers. Independent and quietly opposed to slavery, she felt an immediate mix of fascination and fear upon meeting the boy. She sensed he needed protection from a world eager to destroy him. “What is your name?” she asked when the sheriff brought him.

“Samuel Carter,” he said. “Mama said Samuel means ‘God has heard.’ She said I was born to hear things others couldn’t—know what others didn’t. The voices started talking before I could talk back.” Monroe trusted observation over superstition, but Samuel challenged her rationalism. He spoke with impossible clarity for an illiterate child. He described anatomy better than many medical students. And when he talked about the voices, there was no madness—only calm acceptance.

Monroe proposed a bargain: he could stay as a subject of medical study, treated with dignity and respect. She would provide food, shelter, and education in exchange for cooperation. “If you ever wish to leave,” she promised, “I will help you.” Samuel considered and agreed—but warned her. “The people who come near me—those who carry darkness—they don’t live long. I don’t kill them. I just know when death is coming. Sometimes the voices make sure it happens faster.”

Instead of fear, Monroe’s curiosity deepened. She had studied unusual minds: prodigious memory, instant calculation, perfect musical reproduction. But Samuel was different—bridging exceptional cognition and something beyond her scientific framework. He knew things he couldn’t have learned. He didn’t just intuit; he seemed to receive. Monroe began systematic study in August 1856—documenting statements, behaviors, and predictions.

Samuel described internal organs with perfect accuracy despite never seeing an anatomy text. He predicted illness weeks before symptoms and knew intimate details about strangers—their fears, their secrets, their sins. “How do you know?” Monroe asked. “The voices tell me,” Samuel said. “They come from the swamp—from the dead who don’t rest. People with unfinished business, truths to tell. They use me because I can hear. Mama said it runs in our family.”

The first death after Samuel arrived occurred in September 1856. Marcus Thornton, a wealthy plantation owner, visited Monroe for stomach pain. Samuel recoiled—eyes wide with recognition and horror. “You shouldn’t be here,” he said. “You killed three children—two boys and a girl. You buried them in the old cemetery among unmarked slave graves. Their mothers still search for them.” Thornton blanched, then raged—demanding punishment for “insolence.”

Monroe defended Samuel and expelled Thornton. Three days later, Thornton was found dead in his carriage—officially “heart failure.” His eyes were frozen in terror; his mouth open as if screaming. Marks on his neck looked like finger impressions, though he was alone. Monroe told Samuel. “The voices said the children were waiting on the road,” he replied. “It was time for him to answer.”

Authorities searched Thornton’s cemetery—and found the children’s remains. The enslaved community told of disappearances, screams from his quarters, and a monster masquerading as a gentleman. Samuel had known the details instantly. This was not coincidence. It was something Monroe could not explain. The second death came in October. Reverend Silas Jameson preached charity while profiting from the slave trade.

At the general store, Jameson praised Monroe’s “charity” but warned against “educating these people beyond their station.” Samuel stared at him and spoke: “You don’t believe in God. You sold a woman and her baby to different buyers. She killed herself; the baby died a month later. You hear her crying every night. You drink to sleep.” Jameson turned pale and fled—calling the boy “possessed.”

Two weeks later, Jameson was found dead—slumped over his desk with an empty laudanum bottle. Officially suicide. His eyes held the same terror; unfinished letters apologized to “Sarah” for selling her and her infant. Samuel explained: “He couldn’t live with it anymore. The voices followed him—showed him what happened to the baby.” Monroe warned Samuel: people feared him, and the pattern was becoming obvious. She might not be able to protect him.

Samuel understood but insisted: “Sometimes silence feels like being part of the evil.” The pattern continued. William Drake, a slave catcher known for cruelty, died when his horse bolted and broke his neck—just as Samuel predicted. Catherine Bellamy, who ran a boarding house where enslaved people were held before sale, died in her sleep with a frozen scream. Samuel had said she poisoned food to force silence—and would die of poison “from fear that eats from the inside.”

Each death had a plausible cause, but the pattern was clear. Samuel seemed like a conduit for justice—a vessel for ancestral rage and truth. Monroe’s journals captured her struggle. She tested Samuel’s observation and memory, but his knowledge exceeded any natural explanation. He knew what he could not have witnessed; he predicted outcomes no deduction could reach. “I am forced to conclude,” she wrote, “that Samuel either possesses extrasensory perception or is in contact with something beyond our material world.”

The community’s reactions diverged. White residents whispered “curse,” “evil,” and blamed Monroe for harboring danger. Enslaved people saw Samuel as an avenging angel—a prophet or spirit made flesh—bringing justice where none existed. Old Jeremiah found Samuel at the swamp in February 1857. He spoke of the old ways—African traditions carried across the ocean, kept alive in whispers and warnings.

He explained the sight, walking between worlds, hearing ancestors. Samuel’s gift was not a curse but an ancient connection. Yet Jeremiah warned: white society feared Black power and would come for those who showed too much light. “Learn when to hide,” he said. Samuel knew hiding would soon be impossible. The voices grew louder—showing visions of war, rivers of blood, emancipation, reconstruction, and generations fighting evolving forms of oppression.

He saw Lincoln’s documents and joy followed by terror. He saw future battles where justice remained just out of reach. Exhausted and haunted, Samuel told Monroe: “They’re showing me too much.” He said slavery would end, but new systems would replace it—holding Black people down through law and violence. “Sometimes I wish I was deaf to them,” he confessed.

The turning point came in March 1857 with Benjamin Cole, a slave trader dying of cancer. Cole had the gift too—using it to exploit and break people for profit. When Cole came for treatment, Samuel trembled; the voices screamed warnings. Cole recognized Samuel immediately. “We’re both cursed,” he said. “You pass judgment; I make a living.” Samuel denied the comparison—calling Cole’s use a perversion of the gift.

Cole laughed, claiming the gift “just is”—a tool used based on intent. The confrontation shook Samuel—raising doubts about justice versus vengeance. Monroe told him intent mattered. Cole used the gift to harm; Samuel used his to expose harm already done. Cole died in May 1857, but sent Monroe a confession—detailing the psychological torture he inflicted, listing names and destinations, and asking that the records go to abolitionists.

“Tell the boy he was right,” Cole wrote. “Tell him to never become what I became.” Monroe copied the documents and sent them north to Underground Railroad contacts. Samuel’s doubts remained—questioning redemption and whether remorse mattered to the voices. He kept learning—reading medicine, philosophy, and science—while the voices showed him past and future with relentless intensity.

In September 1857, the ninth and final death forced Monroe to act. Judge Albert Crane, a powerful parish judge, upheld slavery through careful legal opinions and harsh sentences. At a social gathering, Samuel confronted him—reciting the names and numbers of those Crane had condemned and describing a father hanged for protecting his daughter from a rapist overseer. “They’re all waiting,” Samuel said. “Your judgment is coming.”

Crane demanded punishment; men moved to harm Samuel. Monroe shielded him and fled. She told Samuel he had to leave that night; Crane would send men for him. Samuel agreed—saying Crane would die within three days regardless. Monroe arranged for conductors to carry Samuel north along secret routes—giving him documents, money, and letters of introduction. “Will I see you again?” she asked.

“In some futures, yes,” Samuel said. “In all of them, I remember you as the one who saw me as human first.” Samuel disappeared into the night. Three days later, Judge Crane was found dead—apparently of a massive stroke. His eyes were wide, mouth open in a silent scream. Witnesses in the courthouse reported hearing many voices speaking at once. The enslaved whispered the ghosts had come to collect their debt.

Monroe continued her practice until the Civil War. In 1862, she volunteered to treat wounded soldiers, Union and Confederate alike. Her journals theorized Samuel as an evolutionary adaptation—a survival mechanism in oppressed people, a way to identify threats and protect themselves. But she could not dismiss the possibility that Samuel’s voices were exactly what he claimed—communications from the dead.

Monroe died in 1891, arranging for her journals to be sealed for fifty years and donated to a Philadelphia medical college. She wanted to protect Samuel from becoming a curiosity, yet believed future generations could learn from her documentation. Opened in 1941, the journals drew interest from psychology, neurology, and parapsychology. They offered meticulous records—without definitive explanations.

Samuel’s story did not end in Meow Creek. Reports of a Black boy with uncanny abilities appeared in northern states—diagnosing illnesses in Pennsylvania, locating murder victims in Massachusetts, guiding Underground Railroad routes in Ohio. Whether all these accounts were Samuel or proof that his gift was not unique remains unclear. During the Civil War, stories emerged of a Black scout predicting troop movements and identifying spies with uncanny accuracy.

Soldiers described a young man standing on battlefields after the fighting—tears streaming as he spoke to the dead. He recorded final words and names so families could be notified. Union officers wrote of a remarkable Black man named Samuel whose intelligence exceeded anything they had seen. Official records remain incomplete and contradictory.

After the war, sightings became rarer but more disturbing. Samuel appeared where racial violence erupted—lynchings, massacres, riots. Survivors described a thin Black man with ancient eyes documenting names of the dead—bearing witness where history tried to erase. In Colfax, Louisiana, after the 1873 massacre, a survivor said Samuel walked among the bodies speaking to them and recording names “for a record that couldn’t be destroyed.”

The last detailed sighting was in 1899 in Wilmington, North Carolina, after a white supremacist coup and mass murder. Journalist Alexander Manley wrote of a man “in his late 40s, thin and worn,” documenting the massacre “for a record that would outlast the lies.” When asked his name, the man replied, “Samuel—my mother’s name for me. It means God has heard.” After 1899, the sightings ceased.

Samuel became a folk figure in Black communities—sometimes a warning, sometimes hope. Some said he died, finally free of the voices. Others believed he silenced them and lived under a new name. Still others insisted he continued walking among the dead, recording names and stories that otherwise would be erased. Monroe’s journals end with a reflection on meaning rather than mechanics.

She wrote that Samuel was proof of Black intelligence and capability denied by society. Proof that suffering refines the human spirit into something extraordinary. Proof that justice finds unexpected channels when institutions deny it. Whether his voices were literal or metaphor, the results were the same: truths revealed and crimes exposed by a child who should have been crushed but became a force for remembrance.

The story challenges us to confront genius, gifts beyond normal capacity, and society’s response when such gifts appear in those deemed inferior. How many other Samuel Carters existed—brilliant children destroyed before their potential could manifest? How many voices silenced, gifts crushed, possibilities erased by systems designed to deny humanity? Samuel was exceptional, but the conditions shaping him were not.

Every Black child born into slavery faced existential threat and suppression of potential. Samuel survived because some people—his mother, Monroe, conductors—saw him as human and protected him when they could. For every Samuel who found protection, thousands did not. Their stories are lost; their names forgotten; their gifts never realized.

The mystery is not whether Samuel’s voices were real. It is what it means to be human with gifts and intelligence in a world that denies your personhood. How genius survives oppression. How truth finds voice when speaking it is dangerous. How justice asserts itself when institutions deny it. Samuel may have heard the dead—or may have been so attuned to suffering that he sensed injustice like weather.

Either way, he terrified the architects of white supremacy—proof that racial hierarchy was built on lies. His intelligence and gifts challenged every justification for slavery. That is why his story was buried, records destroyed, journals sealed. Samuel Carter was dangerous not because people died around him, but because his life proved Black humanity and potential cannot be erased.

What do you think of this story? Did Samuel truly hear voices from the dead, or was his gift a form of human perception we don’t yet understand? Have you heard family stories of ancestors who knew things they shouldn’t—gifts beyond explanation? Share your thoughts below. If this story moved you, subscribe for more untold histories of extraordinary Black people whose brilliance endured in the darkest circumstances.

Remember: the stories they tried to erase are the ones we must tell loudest. The voices they tried to silence are the ones we must amplify. The lives reduced to property and statistics were full of intelligence, gifts, and humanity that changed the world—even when the world refused to acknowledge it. See you in the next video as we continue uncovering the hidden history of our people.

News

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but…

U.S Nurse Treated a Japanese POW Woman in 1944 and Never Saw Her Again. 40 Years Later, 4 Officers

The rain hammered against the tin roof of the naval hospital on Saipan like bullets. July 1944. Eleanor Hartwell wiped…

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory on Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

End of content

No more pages to load