If Patton hadn’t moved in time, the 101st Airborne wouldn’t have been captured or forced to surrender. They would have been wiped out. December 1944: the Screaming Eagles were surrounded at Bastogne—ammunition nearly gone, medical supplies exhausted, German tanks closing from all sides. Hitler personally ordered their complete destruction. The weather was so bad Allied air support couldn’t fly. No one was coming—except one man refused to accept that reality.

This is the moment Eisenhower realized Patton might be the only general who could save the war—and what he said when Patton actually pulled it off. A story of impossible odds, desperate men, and the phone call that changed everything. Four days—that’s all the 101st had left. Here’s what happened next.

December 19, 1944. The situation room at SHAEF was silent except for grim voices delivering bad news. German forces had punched through American lines in the Ardennes, sowing chaos across a 50-mile front. Worst of all was Bastogne, a small Belgian town nobody had heard of a week earlier, now the most critical position in Europe. The 101st Airborne—plus elements of other units—was surrounded.

Over 10,000 American soldiers were trapped with no clear escape. German forces outnumbered them nearly three to one. Worse, weather grounded Allied aircraft—no resupply and no close air support. Eisenhower stood before the map, studying the bulge in Allied lines, face drawn from lack of sleep. Intelligence updates grew darker: ammo rationed to ten rounds per rifle, artillery shells nearly gone, medical supplies exhausted, wounded packed into freezing cellars, and German attacks intensifying.

“How long can they hold?” Ike asked. The intelligence officer hesitated. “Sir, realistically, four to five days—maybe a week if they’re lucky. After that, they’ll be out of ammunition and supplies. The Germans will overrun them.” Eisenhower’s jaw clenched. Losing an entire elite division would be catastrophic—militarily and psychologically. These were the men of D-Day and Market Garden. Their annihilation at Bastogne would shatter morale.

“What are our options for relief?” he demanded. Staff laid out grim reality. Montgomery contained the northern shoulder but couldn’t attack south quickly. Other U.S. units were locked in desperate defense. Nobody had the strength or position to launch immediate relief—nobody except Third Army, fighting 100 miles south in the Saar. That meant Patton. It always came back to Patton.

Eisenhower had spent years managing Patton’s brilliance, ego, and insubordination. Exhausting. But staring at 10,000 surrounded Americans, he realized something uncomfortable: Patton might be the only general capable of the impossible maneuver required. “Get me Patton,” Eisenhower ordered. “Verdun tomorrow—emergency conference. Tell him to bring plans for offensive operations. He’ll know what that means.”

After staff left, Ike stood alone. Aide Harry Butcher would later record a whisper: “George, for once in this goddamn war, do exactly what I need you to do. Those paratroopers are counting on you. America is counting on you. I’m counting on you. Don’t let me down.” December 19, 1944—the Verdun meeting has become legend—the moment Patton made the promise that changed everything. Often overlooked are Eisenhower’s words—and the weight of his decision.

The atmosphere in Verdun HQ was tense. Eisenhower opened with forced optimism: “The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity, not disaster.” Everyone knew it was the worst crisis since D-Day. Then Ike asked the room to think—really think—how quickly could a relief operation reach Bastogne? Most generals began calculating logistics. Patton spoke first: “I can attack on the 22nd with three divisions.”

Silence. Glances exchanged. Was he serious—or grandstanding? Disengaging from combat, rotating 90 degrees, moving 100 miles in winter, and attacking in 72 hours was beyond anything attempted. Eisenhower locked onto Patton. His response—recorded by multiple witnesses—was measured and deadly serious: “George, I’m not asking for optimism. I’m asking what you can actually accomplish. The lives of 10,000 Americans depend on your answer.”

“The men of the 101st are surrounded, outnumbered, running out of everything. If you say you’ll be there and you’re not, they die—all of them. So I’ll ask again. Can you attack on December 22?” Patton didn’t hesitate. “Ike, I already have three plans prepared. My staff anticipated this meeting. We war-gamed the contingencies. On December 22, Fourth Armored will attack north toward Bastogne. This isn’t a promise. It’s a fact.”

Eisenhower studied Patton’s face—searching for bravado. He found cold certainty. Patton had prepared before the meeting. That level of foresight impressed even Ike. “All right, George. You’ve got your mission. Relieve Bastogne. You have operational freedom to execute.” Then his voice dropped—a tone his staff rarely heard. “Understand this: if you fail—if those paratroopers are lost because you couldn’t deliver—I will personally see that you never command troops again. Not just relief of Third Army. End of career. Am I clear?” “Crystal clear, sir. I won’t fail.”

Afterward, Ike pulled aside his chief of staff, Walter Bedell Smith. Smith’s diary records it. “The boss asked if I thought George could do it. I said it seemed impossible. Ike said, ‘That’s why I’m sending Patton. Impossible is what he does.’” December 20–25, 1944. While Third Army pivoted north, Eisenhower endured the most stressful week of his command. Bastogne situation reports arrived every few hours—each grimmer than the last.

December 21: German artillery pounding continuously; casualties mounting. McAuliffe sends his famous reply to German surrender demand—“Nuts.” Ike allowed a brief smile: “At least their spirit isn’t broken.” December 22: Patton’s forces attacked as promised, but progress was slow—winter, terrain, determined resistance. Bastogne ammunition critical—some units down to five rounds per rifle—medical supplies nearly exhausted—wounded dying for lack of treatment. Eisenhower messaged McAuliffe: “Hold at all costs. Relief is coming.” Privately, in his diary: “I gave George the green light because I had no choice. Now I’m watching the clock and praying.”

December 23: Weather cleared for air resupply. C-47s dropped ammunition, medical supplies, food—buying time, but not much. German attacks intensified; perimeter shrank; some positions overrun; hand-to-hand fighting in streets. Reports indicated a major assault coming—Hitler had ordered the town’s capture at any cost. Ike sent Patton an urgent message: “George, I need maximum effort. The 101st can’t hold much longer. Whatever you’re doing, do it faster.”

December 24, Christmas Eve. Ike spent the night in his office, unable to rest. Staff said he looked ten years older than a week ago. Reports showed Third Army still fighting miles short. At current pace, they might not arrive in time. Ike drafted letters to families of the 101st—notes he would send if the division was lost—to McAuliffe’s wife, to the chaplain’s family, to families of men he had spoken with. An aide found him late—surrounded by unfinished condolence letters. “I hope I don’t have to send these,” he said.

December 25, Christmas Day. Still no breakthrough. Ike attended chapel but couldn’t focus—checking messages every fifteen minutes. Nothing. The 101st still surrounded; Third Army still fighting to reach them; time running out. December 26, 1944, 4:50 p.m.—the phone rang. Ike’s aide answered, turned pale. “Sir, it’s General Patton. Urgent.” Eisenhower grabbed the phone. “George—” “Ike, we’re through. Fourth Armored made contact with the 101st at 1650 hours. The corridor is narrow, but open. We’re pushing supplies and reinforcements now. Bastogne is relieved.”

For several seconds, Ike couldn’t speak. His hand gripped the phone until his knuckles whitened. Staff saw the tension leave his shoulders; his eyes closed briefly. “George—say that again.” “We’re through to Bastogne. The Screaming Eagles are safe. They’re battered to hell, but they held. We got there in time.” Ike’s voice cracked. “George—thank God. Thank you. You did it. You saved them.”

Patton, uncomfortable with sentiment, replied gruffly. “Just doing my job, Ike. Those paratroopers did the real work. We just knocked on the door.” “No, George—don’t diminish this. You moved an army 90 degrees in a blizzard and broke through in four days. That’s not just doing your job. That’s why you’re invaluable. Despite everything, all our conflicts—this is why.”

After hanging up, Ike turned to his staff—eyes wet, tears he didn’t hide. “Gentlemen, General Patton has accomplished something I will remember for the rest of my life. He saved 10,000 Americans who were hours, maybe minutes, from annihilation. He did what I asked when I asked—against odds everyone said were impossible. George S. Patton is the most difficult subordinate I’ve ever commanded—and without question one of the finest battlefield commanders America has produced.”

Ike sent official messages: congratulations to the 101st for heroic defense; commendations to Third Army for relief; a report to the War Department announcing Bastogne’s relief. He also sent a personal telegram to Patton: “George, words cannot adequately express my gratitude and admiration. You gave your word you would be there. You kept it. In doing so, you saved not just 10,000 soldiers, but possibly the entire Ardennes campaign. ‘Well done’ does not cover it. This operation will be studied for generations. I am proud to have you under my command. —Ike.”

That evening, Ike’s aide found him staring at the map showing the narrow corridor into Bastogne. “Four more hours,” Ike said quietly. “That’s all George had. Four more hours and the 101st would have been overrun. He made it with four hours to spare—four hours between salvation and annihilation.” In the days and years after, Ike’s words about Patton evolved—from immediate gratitude to historical assessment—shaping how both men would be remembered.

December 27, 1944—official statement: “The relief of Bastogne by elements of Lt. Gen. Patton’s Third Army represents one of the war’s outstanding achievements. The speed and coordination in disengaging from the Saar, pivoting north, and attacking through difficult weather and determined resistance demonstrates the highest operational art. The defenders of Bastogne and their relievers have written a new chapter in American military history.”

To General Marshall, Ike was blunt: “George Patton just saved my command. If Bastogne had fallen with an airborne division lost, the psychological impact would have been catastrophic—raising questions about Allied strategy, American competence, and my leadership. Patton prevented that disaster. Whatever frustrations I’ve had with him—and they are many—this operation justifies every difficult decision to keep him in command.”

To Montgomery, Ike wrote: “Patton’s relief of Bastogne demonstrates American operational capability at its finest. I know there were concerns about U.S. effectiveness. Bastogne should put those to rest.” In his diary, Ike admitted the emotional weight: “I have spent years managing George’s ego and insubordination. Times I wanted to fire him. Bastogne answered whether he was worth the trouble. He is—because when it mattered most, when 10,000 Americans faced annihilation, George delivered—exactly when and how he promised. That’s a great commander.”

On January 2, 1945, Ike sent Patton a follow-up: “George, reflecting on Bastogne—what you accomplished goes beyond tactical brilliance. You gave those paratroopers hope when they had none. You proved Americans can execute complex operations under impossible conditions. You changed how Germans view American capability. Most importantly, you saved lives—literally. Every man of the 101st who came home owes that to your speed and aggression. That legacy is worth more than medals or promotions.”

In Crusade in Europe, Ike wrote: “Patton’s relief operation stands as one of the war’s pivotal moments. The rapid movement of three divisions, the coordination required, and the aggressive execution under terrible conditions showcased American excellence. History will debate many aspects of the war; Bastogne’s relief is beyond debate—operational genius.” In 1964, asked about his hardest decisions, Ike replied: “Trusting Patton to relieve Bastogne was agonizing. I was betting everything—10,000 lives and our position—on a difficult subordinate. But George was the only one who could do it. When he succeeded, I felt relief and gratitude beyond words. ‘We’re through to Bastogne’—those four words may be the most important I heard during the entire war.”

His final assessment in 1965: “History will remember many generals, but few for saving an entire division from annihilation through pure operational brilliance. That was George S. Patton at Bastogne. Whatever else he was—difficult, controversial, flawed—he was the man who refused to accept those paratroopers were doomed. He promised to save them—and he did.” Bastogne wasn’t just a military operation. It was the moment Eisenhower realized that genius—however hard to manage—is worth every frustration when it delivers miracles.

If this story of impossible odds, desperate decisions, and the words that define legends moved you, subscribe now. We’re bringing untold moments, private words, and the human drama behind history’s greatest battles. Hit the bell, drop a comment on leadership under pressure, and share with anyone who needs to hear what’s possible when someone refuses to accept defeat. Remember: sometimes the most difficult people achieve the most extraordinary results.

News

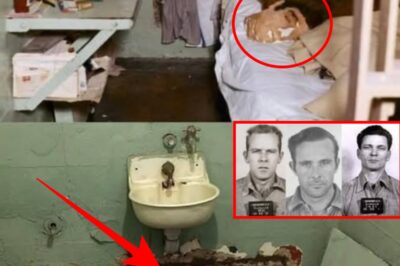

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

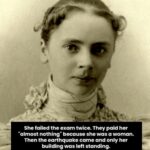

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid….

End of content

No more pages to load