The Cure That Broke Creswell

They called it a cure—corrective association, a physician’s theory that sounded sophisticated enough to quiet doubts and dangerous enough to move quickly. In Creswell Manor, a widow believed science could tame shame, social panic, and the ghost of a husband’s last command: “Fix him. Whatever it takes.” She bought a man like medicine, placed him at her son’s side like a tonic, and waited for normal to appear. What she found instead in the attic—dust glowing in a single shaft of light, her son on his knees, begging—didn’t confirm illness. It exposed truth. And that truth reached back twenty-five years to a garden kiss Catherine Creswell had buried so deep she’d taught herself to forget.

Creswell: A House That Hid Anxiety in Lace

Spring 1849, Henrico County. Creswell Plantation rose from the James River fog like old money made into architecture—white columns, black shutters, imported furniture and portraits purchased from minor European nobility. The gardens, designed by a Charleston landscaper, framed respectability like stage scenery. Everything spoke of stability. Everything except the heir.

Jonathan Creswell had been politely labeled since childhood—sensitive, delicate, artistic. He cried easily, read poetry, refused hunting, showed no interest in field operations or ledger mastery. His father died when Jonathan was sixteen, leaving a fortune, a widow, and a demand: do not let our name “die in shame.” Catherine was forty-two now, intelligent, capable, and cornered by whispers that grow louder in rooms where reputations live.

A Letter That Sold Science as Salvation

The drawing room smelled of beeswax and magnolia drift. A letter from a sister in Richmond mentioned a physician newly returned from Edinburgh—Dr. Wendell Briggs—and “new theories” about irregular temperaments in young men. He called it masculine insufficiency syndrome. Treatment: corrective association with an idealized masculine figure, physically impressive, emotionally reserved, confident. The afflicted would observe, internalize, realign.

Then came the practical line that crossed any decent boundary with professional ease: use an enslaved man of suitable traits. The power dynamic would reinforce masculine authority for the patient while exposing him to a model he lacked. Catherine read the words again and again, hands trembling for reasons beyond medicine. It felt like permission, like a ladder built over a wall she’d never thought she could climb. She wrote back that afternoon.

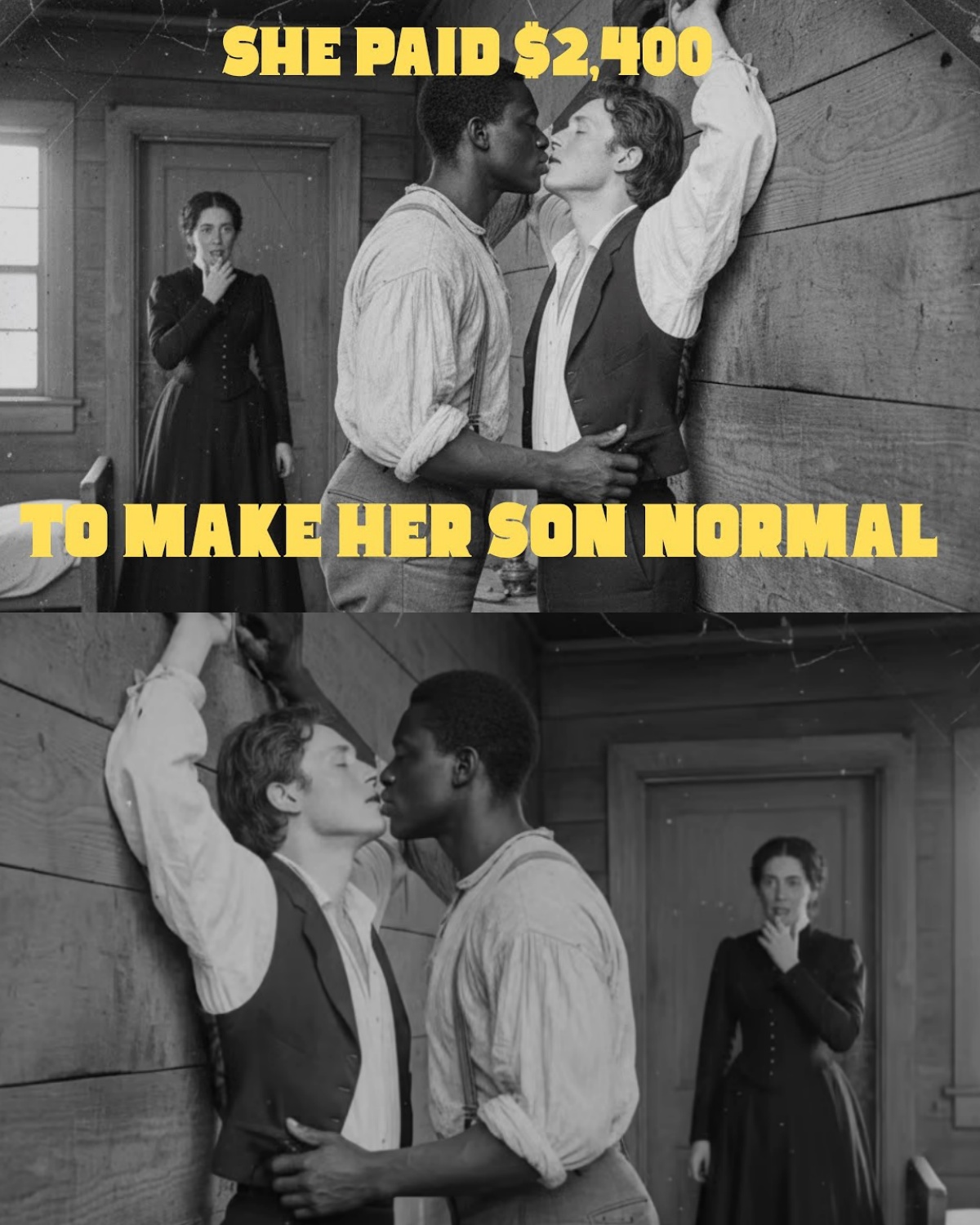

Buying a “Cure”

The overseer returned from Richmond’s auction houses with a man named Elijah—six-foot-two, deliberate, a presence that felt larger than his body. Dark mahogany skin flashed intelligence in spring light, eyes reading rooms. He had been a house servant for a Richmond merchant, could read and write, carried himself with studied calm.

In the service hall’s cooler air, Catherine confronted the unsettling detail that most enslaved people displayed fear in owners’ presence. Elijah did not. His submission looked performed, a posture rather than a feeling. “You understand why you were purchased?” she asked. “No, ma’am,” he said, voice precise. She explained the assignment: be a companion, a teacher; harden Jonathan; make him practical; model masculinity. “If I fail?” he asked—with a tone that wasn’t fear so much as assessment. “You’ll be sold south,” she replied. “I paid $2,400. I expect results.” He said, softly, almost to himself: “Results. That’s what everyone expects.”

Silas led him to a cottage behind the stables, isolated by oaks. Catherine scheduled four o’clock. She felt like she had started something she could not stop—because she had.

The First Meeting: Recognition Wearing Panic

The study still held the smell of old pipe tobacco from a man eight years gone. Jonathan—poetry in hand, orbs of auburn hair catching light—stood behind his father’s desk like furniture might shield him. When Elijah entered, Jonathan’s body betrayed him: flushed face, shallow breaths, hands fumbling a pen, chair scraping, sitting-standing-sitting. Catherine saw it—recognition, the kind that rewrites a room in one glance. It was the reaction she had had at seventeen when she saw Elizabeth Thornton by a rose hedge and understood something she’d been taught to erase.

“Say hello properly,” Catherine prompted. “Hello,” Jonathan managed. Elijah nodded, gentle voice: “I look forward to working with you.” “Working with you” landed in the room with implications neither could say aloud. Catherine left, fighting the sense that the plan had already slipped.

Two Hours That Changed the Plan Without Admitting It

Behind the closed door, awkward silence turned into literature. Elijah quoted Keats and discussed Romantic poetry with ease. Jonathan lit up—animated, bright, alive in a way Catherine hadn’t seen in years. He confessed uselessness in practical matters. Elijah described learning to read in secret, becoming what owners needed to survive. They spoke like two people who had found water in a dry place.

Catherine checked in and saw them comfortable—too equal. Elijah’s expression wasn’t the defensive blankness enslaved people wore; it was genuine interest. Catherine went to bed unsettled—not by failure, but by success of the wrong kind.

Corrective Association Becomes Conversation

A routine formed. 8:00 a.m.—Elijah in the study. Ostensible topics: accounts, tobacco cultivation, operations. Real topics: grief, loneliness, survival, ideas. Catherine observed from a distance: Jonathan stood straighter, spoke with confidence, even accepted a Richmond invitation briefly. The physician’s theory seemed to be working in public. In private, the work of being human had begun.

Elijah was prepared to endure contempt, then found something else: a young owner who hated the idea of owning people and asked opinions rather than extracting obedience. That difference made distance harder. You could shield against cruelty. Against kindness, you must calibrate.

Naming What Everyone Already Knew

Late May turned the study into a greenhouse. Jonathan asked the question that changes everything: “Have you ever felt like you’re pretending to be someone you’re not?” Elijah: “Every day.” Jonathan: “I’ve never felt this way about a woman.” He spoke the pattern out loud—how attraction existed but along a different axis than the world permitted.

Elijah did not flinch. He spoke of survival: learning when to hide and when to breathe; living without confusing survival for life. Jonathan edged closer to the line all fear draws. “I don’t want to just survive,” he said. Elijah said the word that makes complexity bearable: “Carefully.”

They stood inches apart, heat between bodies and history radiating off furniture. Jonathan refused to cross consent’s line. Elijah put it on the table without lying: feelings exist inside coercive structures; distinguishing want from adaptation is difficult. But truth can still live there. “When I’m with you,” Elijah said, “I feel more myself than I have in years.” That sentence rewrote the room.

They kissed. It was awkward, gentle, alive. Outside, Catherine paused at the door and heard “I want to touch you.” The sentence made her remember Elizabeth Thornton’s garden and the word sick that had murdered a future.

A Mother at the Door

Catherine did not burst in. She walked to her room and wrote two letters: one to Dr. Briggs—clinical language asking what to do when a cure creates attachment; one to Elizabeth she would never send—confessing that twenty-five years of respectability had required burial of self. She burned both—first with respect, second with grief. Then she made a decision many would judge harshly, some would call brave: she would watch and wait.

She let the routine continue—eight months of allowing her son the one thing she had denied herself. Jonathon became more alive and, ironically, more competent in the world his father had wanted him to master. The study became sanctuary. Catherine protected it without naming protection.

The Attic: When Private Truth Meets Public Fear

Late March 1850, raised voices sent Catherine up narrow stairs to storage rooms where old furniture and old clothing slept under dust. The light cut golden diagonals through motes. Jonathan was on his knees, sobbing, arms around Elijah’s waist. Elijah’s hand moved through Jonathan’s hair—tenderness that even Catherine could not file as inappropriate. It was too obviously real.

“Please don’t leave,” Jonathan said. “I’ll die if you do.” Elijah spoke the sentence that defines impossible love in an oppressive world: “You don’t own me. You own my body, labor, legal status, but not me.” They saw Catherine. Elijah’s posture snapped into survival; tenderness evaporated into safety. Jonathan went bloodless.

Catherine made a sound—pain more than anger—because what she saw wasn’t deviance. It was her own buried reflection. Seventeen in a garden. A kiss. Shame. A life. A death-in-life. She understood at once and entirely: she had given her son a key to a door she had locked for herself. And now, because of law and society, she might have to make him close it.

Intervention Without Hypocrisy

Jonathan tried to speak. Catherine raised a hand. “Get out,” she told Elijah—temporarily, to create a space she and her son could stand in. They sat on the dusty floor in clothes designed for ballrooms and ledgers. Catherine spoke first, with the honesty that buys trust: “When I was seventeen, I kissed a woman in a garden. I buried it. I married your father. I have been dead inside for twenty-five years.” Jonathan’s face changed. She told him she had watched to protect that one place where he felt alive. Then she said the sentence no parent wants to say but must in certain worlds: “This cannot continue as it has. Society will not allow it. The law will punish it. You must choose.”

She offered two choices, neither good, both survivable:

– Separation: Elijah sold far away; time dulls pain; Jonathan marries; respectability saved; soul compromised.

– Secrecy: Elijah stays; relationship hidden; public fiction maintained; private truth preserved; lifelong exhaustion included.

It was the honesty Catherine had begged for at seventeen and never received. It was not justice. It was the best available in a locked system.

Three Days of Night

Jonathan did not sleep. He told Elijah everything. Elijah refused to make the decision for him and explained why: he was enslaved; his life did not belong to him; the only agency here was Jonathan’s. That brutality of truth did not erase feeling. Elijah said what both knew: “I don’t want to leave. This is the closest thing to real I’ve had. But choosing hidden love is choosing a kind of suffering. Are you strong enough for it?”

Jonathan had spent his life suffering silently. Now he decided to suffer with meaning. On the morning of day three, he told his mother: “I choose him.”

Catherine—not the society woman, not the widow performing resilience, but the person who buried herself to survive—looked at her son and said, “Okay.” It was the most dangerous, most compassionate word she had ever spoken in that house.

The Architecture of Secrecy

They continued inside fictions Catherine built and maintained. In public, Elijah was Jonathan’s valet—respectable, useful, always near. In private, he was partner—human, equal, necessary. Catherine lied when needed, deflected when prudent, shielded when possible. She became the keeper of an impossible truth because she had failed to keep her own.

Years passed. Social pressure eventually required a marriage. Jonathan chose a woman who understood and wanted companionship without intimacy. Elijah remained, officially servant, actually family. They grew old within limits and found joy in margins. It was not fair. It was real.

What This Story Proves (and Refuses to Exploit)

– Corrective association was a pseudoscientific excuse for coercion. It dressed cruelty in medical terminology. It did not cure. It exposed.

– Buying a human as “treatment” is a crime, even when told as historical narrative. The harm is structural, not only personal.

– Love under power imbalance is not simple. Elijah’s honesty about consent does not erase the poison of ownership. It acknowledges it and navigates the least harmful route available.

– Catherine’s decision to protect, then force a choice, then accept secrecy isn’t heroic. It is tragic and human. She chose compassion inside constraints that never let compassion be enough.

– Survival within oppressive systems often requires half-lives. A half-life isn’t failure. It’s endurance with meaning.

Investigative Notes: How the Pattern Holds

– Physician theories like Dr. Briggs’s were part of a 19th-century trend that pathologized nonconforming behavior under moralized medicine. “Masculine insufficiency” is consistent with historical pseudoscience used to police identity.

– Plantation dynamics: overseers, auction logistics, literacy among enslaved household servants, cabin isolation by function—match documented patterns across Virginia and the Upper South.

– Consent and power: the narrative explicitly acknowledges that Elijah’s feelings exist within coercive structures. He articulates the difficulty of separating survival adaptations from authentic desire. That acknowledgment is vital and consistent with trauma-informed readings of enslaved relationships.

– Social strategies: companions married for mutual protection; hidden partnerships; privacy maintained through routine and plausible roles—these align with known survival practices in rigid societies.

This isn’t a courtroom brief. It’s a reconstruction of human choices inside systems designed to crush them. The tension lives in ethics, not gore.

The Mother Who Refused to Kill Her Son to Save Him

Catherine burned two letters and kept a promise she never received: she gave her son real choices, then stood beside the consequences. She did this knowing that secrecy would erode, that fatigue would accumulate, that danger would never disappear. She did it because the alternative—separation that preserved reputation while murdering truth—was what had killed her for twenty-five years.

We rarely call that bravery because it doesn’t look heroic. It looks like lying well, scheduling carefully, inventing reasons for proximity, and protecting edges. But in a world where respectability demanded internal murder, Catherine became something unexpected: a keeper of life inside polite society’s coffin.

The Cost of Half-Lives—and Why They Are Still Lives

Jonathan did not get a happy ending. No one in such a system does. He got daily truth in private and performance in public. He learned to carry both without letting either erase the other. Elijah did not get freedom in law. He got dignity in a house that acknowledged humanity inside an economy that did not. His honesty kept them from pretending complexity was consent.

They aged into roles that would never be celebrated and refused to let that fact determine value. The roses of Creswell did not know politics. The study books did not require permission to be beautiful. In their margins, they wrote a life.

The attic door doesn’t slam. It stays open just enough to let dust and memory in. The study’s clock ticks on the mantle, indifferent to reinvention. The river fog rolls as it always has, covering fields where names were turned into ledger lines and then—sometimes—returned to human shapes in quiet rooms.

The cure at Creswell was never medicine. It was a mirror. Catherine paid $2,400 to fix a son. Instead, she found the truth she had refused at seventeen—alive in the one place she feared and hoped it would be. That is the crime and the redemption both: a society that calls love sickness, and a family that decides to treat the world’s illness by keeping the truth alive, even if only in shadow.

The attic light holds. The mother breathes. The son chooses. The man stands, still himself.

News

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but…

U.S Nurse Treated a Japanese POW Woman in 1944 and Never Saw Her Again. 40 Years Later, 4 Officers

The rain hammered against the tin roof of the naval hospital on Saipan like bullets. July 1944. Eleanor Hartwell wiped…

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory on Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

End of content

No more pages to load