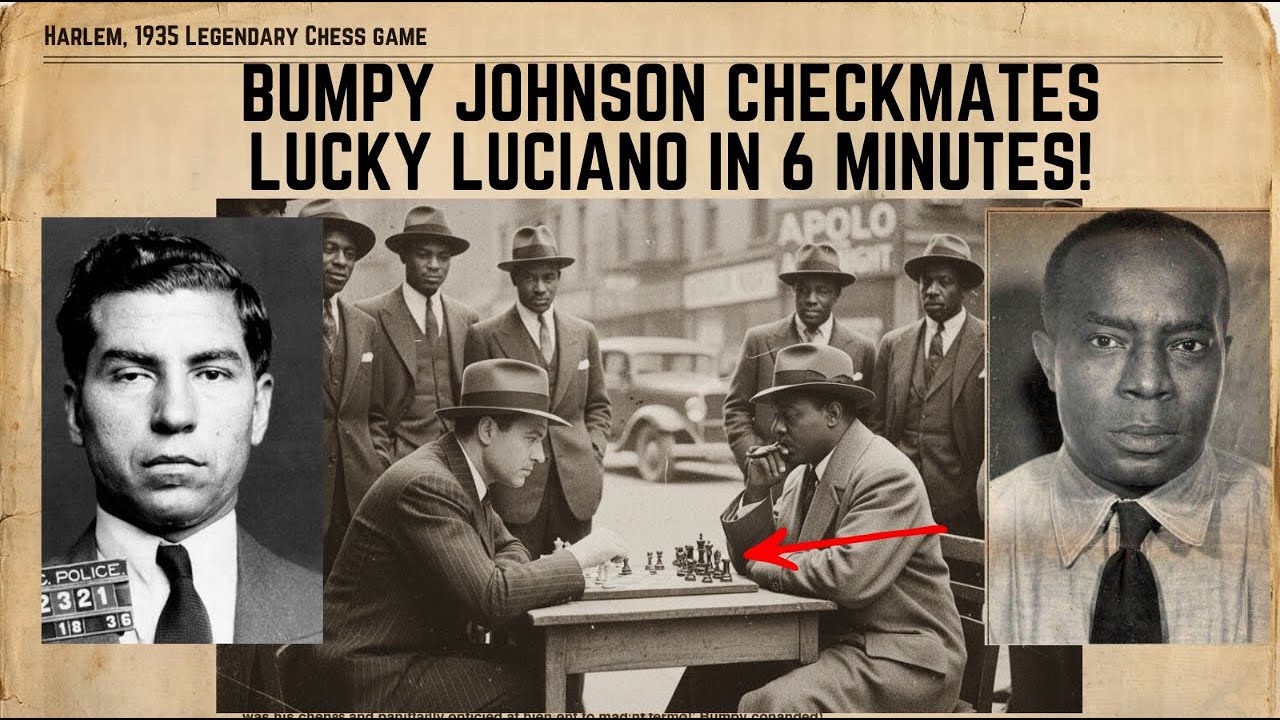

Harlem, New York. On Friday evening, September 20th, 1935, Charles “Lucky” Luciano walked into the back room of the Exclusive Club on 142nd Street, carrying a chess set that had belonged to his mentor, Arnold Rothstein. He was 37 years old, the most powerful organized crime boss in New York, the man who’d reorganized the Italian‑American Mafia into the modern Commission system. Under his leadership, chaotic gang warfare of the 1920s had been replaced with order and structure.

Sitting across the table waiting for him was Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, 30 years old, Stephanie St. Clair’s chief enforcer and strategist. Johnson was rapidly building a reputation as someone who understood strategy at levels that transcended simple violence or intimidation. He was not just muscle; he was a thinker.

The challenge had been issued three days earlier through intermediaries. Luciano wanted to play chess with Johnson, just the two of them and witnesses. No business discussions unless both parties agreed afterward.

On the surface, it was just a game—to see who thought better, who understood strategy, who deserved respect based on demonstrated intelligence rather than sheer power or established status. But everyone in Harlem’s criminal underworld understood what it really meant.

This was Luciano testing whether Johnson deserved to be treated as an equal. Whether a 30‑year‑old Black man from Harlem could match wits with the white mob boss who ran New York’s entire criminal underworld.

The outcome of this chess game would determine how the Italian families treated Harlem’s independent operators going forward. Would they be treated with respect as equals—or pressured to surrender as subordinates?

The back room of the club was packed with approximately 50 witnesses, 25 invited by Luciano, 25 by Johnson. The atmosphere was electric with tension. Nobody was talking. Everyone watched as these two men, representing different races, backgrounds, and organizations, sat down to decide through pure strategic thinking who deserved respect and who would be forced into submission.

Luciano sat down and began arranging the chess pieces with practiced efficiency. He was dressed impeccably: an expensive suit custom‑tailored in Italy, a silk tie that cost more than most working men earned in a month, a diamond ring sparkling under the room’s lights. He carried himself with absolute confidence—the confidence of someone who’d never lost at anything that truly mattered.

He clearly expected to win this chess game as easily as he’d won control of New York’s criminal underworld. Johnson entered at 8:15 p.m., accompanied by Stephanie St. Clair, who greeted Luciano politely before taking a seat among the witnesses. Johnson was well‑dressed but simple: dark suit, white shirt, no jewelry, no ostentation.

He carried himself with a quiet confidence that contrasted sharply with Luciano’s more obvious swagger. Where Luciano projected power and wealth, Johnson projected intelligence and focus.

“Mr. Luciano,” Johnson said as he sat down across the table. “Thank you for the invitation. I’ve been looking forward to this.”

Luciano smiled—a condescending smile that suggested he expected to beat Johnson easily and was already rehearsing how gracious he’d be in victory.

“I’ve heard you’re good at chess, Bumpy,” Luciano said. “I’ve heard you think several moves ahead, that you understand strategy beyond just knowing the rules. Let’s see if that’s true. Let’s see if you can actually compete with someone who learned chess from Arnold Rothstein himself.”

Johnson nodded toward the board, ignoring the implied insult. “Your move, Mr. Luciano. Let’s find out.”

**The six‑minute game that changed New York was about to begin.**

The game started at exactly 8:17 p.m. Luciano opened with the King’s Pawn, moving his pawn from e2 to e4— a classical, aggressive opening favored by players who want to control the center quickly and create immediate pressure. It was the opening chess masters had used for centuries, and one Luciano had used successfully hundreds of times.

Johnson responded immediately and without hesitation with the Sicilian Defense, moving his pawn from c7 to c5. It was one of the most aggressive and complex responses to 1.e4, creating immediate imbalance and inviting tactical complications.

It was also, as many in the room silently noted, a defense literally named after Sicily—Luciano’s ancestral homeland.

The room was absolutely silent, except for the soft click of chess pieces on wood. They played rapidly, pieces moving back and forth with increasing speed as the position developed. Luciano played aggressively, developing his knights and bishops quickly, trying to dominate the center and create early pressure against Johnson’s position.

He was confident, moving fast, clearly a man who’d played thousands of games and trusted his instincts. Johnson, by contrast, was calm, deliberate, each move precise and purposeful. He wasn’t trying to match Luciano’s aggression; he was building something deeper.

He was creating a structure, a trap that wasn’t obvious yet, one that would only reveal itself when it was too late for Luciano to escape.

By the fourth minute of the game, Luciano appeared to control more territory on the board. His pieces were actively placed, creating multiple threats and forcing Johnson to respond defensively.

Luciano was smiling, clearly convinced that his aggressive opening was working exactly as he’d planned, that Johnson was being pushed back, that victory was near. The witnesses on Luciano’s side of the room were smiling too—confident their boss was proving his superiority over this upstart from Harlem.

On Johnson’s side, faces were tense. His supporters worried their champion was being overwhelmed by Luciano’s relentless attack.

Then, at approximately the four‑and‑a‑half‑minute mark, Johnson made a move that drew gasps from several knowledgeable observers. He moved his queen forward aggressively, seemingly exposing his most powerful piece to capture.

It looked like a terrible mistake—the kind of blunder amateurs make when nervous or desperate, the kind of move professional players almost never make. Luciano’s smile widened immediately. His eyes lit up as he recognized what he believed was a fatal error.

He reached for his rook without hesitation, ready to capture Johnson’s exposed queen and essentially win the game in the opening phase.

“That was a mistake, Bumpy,” Luciano said confidently, his hand closing around the rook. “You can’t expose your queen like that against a strong player. You just lost this game.”

Johnson leaned back slightly in his chair, completely calm, and answered with absolute confidence. “Take it,” he said, “and see what happens.”

Luciano captured Johnson’s queen with his rook, removing Johnson’s most powerful piece from the board. The witnesses on Luciano’s side began smiling and nodding, certain the game was effectively over.

On Johnson’s side, the mood shifted to despair. They believed he’d thrown away any chance of victory with a catastrophic blunder.

And then Johnson moved his knight.

The knight landed on a square that accomplished three devastating things at once. It put Luciano’s king in check, forcing an immediate response. It attacked Luciano’s queen, threatening his most powerful piece. And it unleashed a discovered attack from Johnson’s bishop on Luciano’s rook—the very piece that had just captured Johnson’s queen.

Luciano’s smile vanished, replaced by shock and dawning horror. He stared at the board, his hand frozen midair, suddenly understanding what had just happened. Johnson hadn’t blundered at all.

He had sacrificed his queen intentionally—deliberately, brilliantly—to lure Luciano’s rook into a trap and to create multiple simultaneous threats that Luciano could not defend against. The room erupted in whispers and exclamations as witnesses on both sides grasped what they were seeing.

This wasn’t a mistake. This was genius. It was strategic thinking that transcended ordinary chess and entered the realm of art.

Luciano was forced to move his king to escape the knight’s check. But by moving his king, he exposed his queen to capture and left his rook— the one that had taken Johnson’s queen—hopelessly trapped by Johnson’s bishop.

In a single combination, Johnson had turned what looked like a catastrophic loss into an overwhelming advantage. Luciano had effectively traded his queen and rook—worth 9 + 5 = 14 points—for Johnson’s queen worth 9 points.

Johnson was now ahead by five points of material, an advantage that is usually insurmountable at high levels of play.

Worse than the material deficit was the positional disaster. Luciano’s king now stood exposed in the center of the board with too few defensive pieces remaining.

Johnson’s forces—two rooks, a bishop, a knight, and several advanced pawns—were perfectly coordinated, ready to launch a decisive attack. Luciano tried to mount a defense, moving his pieces frantically, trying to shelter his king, to create counterplay, to find any way to survive.

But it was hopeless. Johnson’s pieces worked together like a perfectly tuned machine, each move generating multiple new threats, each threat forcing Luciano into passive, defensive responses.

Exactly six minutes after Luciano had made his first move—at 8:23 p.m. on September 20th, 1935—Johnson slid his rook to the back rank, placing Luciano’s king in check. Luciano studied the board desperately for about 30 seconds, searching for any move that would save his king, any escape route from the trap.

There was none. Every square the king could move to was controlled by Johnson’s pieces. Every piece that might block the check was pinned or would leave the king in check from another angle.

Checkmate.

The room remained absolutely silent for several seconds as everyone processed what they’d just witnessed. Then the silence broke—first in murmurs, then in applause—from Johnson’s supporters, who had just watched their champion dismantle New York’s most powerful mobster through pure strategic brilliance.

Luciano stared at the board in disbelief, his mouth slightly open, his confidence shattered. Six minutes. He’d been destroyed in six minutes.

The most powerful white mobster in New York had been demolished by a 30‑year‑old Black man from Harlem, using the Sicilian Defense—an opening named after Luciano’s own ancestral homeland.

Johnson leaned forward slightly, studying the board where Luciano’s king lay trapped with no escape. Then, with a slight smile witnesses would remember for decades, he delivered the line that became legend.

“The Sicilian Defense, Lucky,” he said. “Guess I’m more Italian than you are.”

The room erupted in laughter. Nervous laughter from Luciano’s men, unsure how their boss would react to being mocked after such a defeat. Genuine, delighted laughter from Johnson’s side, who appreciated the perfect timing and sting of the joke.

The remark worked on multiple levels at once. Johnson had just beaten a Sicilian mob boss using a chess opening named after Sicily, outmaneuvering a man who considered himself America’s most strategic criminal mind.

The joke referenced the opening, playfully suggested that Johnson understood “Italian” strategy better than an actual Italian, and wrapped a sharp insult in enough humor that even Luciano couldn’t reasonably take offense.

For several tense seconds, no one knew how Luciano would respond. Would he be furious? Would he lash out at being mocked in front of 50 witnesses? Would a moment of humor spill into violence?

Then Luciano leaned back slowly, rubbing his eyes as if he still couldn’t believe what had happened. When he finally looked up at Johnson, his expression had shifted—from shock to genuine respect mixed with appreciation for Johnson’s wit.

Luciano began to laugh. Not forced or angry laughter, but genuine amusement that acknowledged both Johnson’s chess brilliance and his perfect punchline.

“You know what, Bumpy? You’re right,” Luciano said. “You just proved you’re more Sicilian in your strategic thinking than I am. That queen sacrifice—making me think I was winning when I was actually walking into a trap—that’s exactly the kind of strategic deception Sicilians are supposed to be famous for. And you executed it perfectly, while I fell for it completely.”

Luciano stood up slowly, still glancing at the board as if hoping it would reveal where he’d gone wrong. When he finally looked directly at Johnson, his face showed genuine, unforced respect—respect that crossed the racial and ethnic barriers that dominated 1930s America.

“Six minutes,” Luciano said quietly, his voice carrying a mix of disbelief and admiration. “You beat me in six minutes. I’ve played chess for 20 years. Arnold Rothstein taught me personally. I’ve beaten some of the best players in New York, legitimate chess masters who study the game professionally. And you just destroyed me in six minutes, using a strategy that made me look like an amateur.”

He extended his hand across the table.

“You earned my respect tonight, Bumpy,” Luciano continued. “You didn’t just beat me at chess. You demonstrated intelligence at a level I rarely encounter. You think strategically. You plan ahead. You understand psychology well enough to manipulate your opponent into making mistakes.

“That queen sacrifice—I thought you’d blundered. I thought I was winning when I captured your queen. But you were setting a trap, making me overconfident so I’d play less carefully. Then you destroyed me with pieces I’d thought were less important than the queen I’d taken. That’s brilliant strategic thinking that goes beyond just knowing chess. That’s understanding human psychology and using it as a weapon.”

Johnson stood and shook Luciano’s hand firmly.

The room watched intently. Two men from completely different worlds—Italian and Black, downtown and Harlem, Commission boss and street strategist—shook hands with genuine mutual respect after a six‑minute chess game that had transcended race, hierarchy, and expectation.

Then Johnson spoke five words that would be quoted in criminal circles, prisons, books, and movies for the next 80 years. Five words that perfectly encapsulated his philosophy of life and competition.

“I don’t play to lose.”

The room fell silent again. Everyone there understood they had just heard something bigger than a post‑game boast.

“I don’t play to lose” was not just an explanation of why Johnson had won. It was a statement about how he approached every challenge, every contest, every situation where outcome depended on preparation and strategy rather than luck.

Luciano regarded Johnson for a long moment and then laughed again—the real laugh of a man recognizing a truth that resonated deeply. “No,” he said, still smiling. “I guess you don’t. And I respect that more than anything.”

“You didn’t come here hoping to win or trying not to embarrass yourself,” Luciano continued. “You came here prepared to win, confident you would win, and you executed your strategy perfectly. That’s the mindset that separates successful people from failures in any business—legitimate or criminal. You don’t play to lose. Neither do I, usually—though tonight, you proved I should have prepared better.”

Luciano then turned to address the entire room, raising his voice so all 50 witnesses could hear. “Everyone here just watched Bumpy Johnson beat me at chess in six minutes using the Sicilian Defense, which is perfect, because he just proved he’s more Sicilian in his strategic thinking than I am.”

“That wasn’t luck. That wasn’t a fluke. That was superior intelligence and superior strategic preparation.”

“I want everyone in this room to understand something important,” Luciano said. “Bumpy Johnson isn’t just some street enforcer who takes orders. He’s a strategist who thinks several moves ahead, who sets traps you don’t see until you’ve already walked into them, who understands psychology and uses it to make opponents commit fatal mistakes.”

“He deserves respect as an intellectual equal—not just from me personally, but from every person and every organization I influence or control.”

Luciano paused and looked directly at the witnesses on his side—Italian mobsters, politicians under his thumb, businessmen tied to his operations.

“Harlem’s operations—Stephanie St. Clair’s operations, Bumpy Johnson’s operations—are not going to be pressured by my organization anymore,” he declared. “They’ve earned autonomy through demonstrated intelligence.

“And anyone who works for me, or who wants my support, needs to understand that underestimating Bumpy Johnson because he’s young, or Black, or less established than me, is a mistake that will cost you everything. Respect intelligence wherever you encounter it, regardless of what package it comes in. That’s a lesson I just learned the hard way—and it’s a lesson I want everyone here to learn from what you just saw.”

The witnesses on Luciano’s side nodded, understanding their boss had just fundamentally reshaped the relationship between Italian families and Harlem’s operators. On Johnson’s side, people smiled, realizing their champion had won something far more valuable than a single chess game.

He had earned respect that would translate into operational freedom for Harlem’s independent operators.

From her seat among the witnesses, Stephanie St. Clair smiled with quiet satisfaction. She had sent Johnson to this chess game knowing intelligence would be tested, knowing the result would determine Harlem’s future relationship with the Italian families.

Johnson had delivered perfectly. He had demonstrated such overwhelming intelligence that even Lucky Luciano couldn’t deny it, earning respect that would give Harlem the freedom to operate autonomously without constant pressure from the Italian mobs.

**The second game: one week later.**

The story of how Bumpy Johnson beat Lucky Luciano at chess in six minutes spread through New York’s criminal underworld with incredible speed. By the next morning, everyone—Italian families, Irish gangs, Jewish operators, Black independents—had heard about the game and about Luciano’s public acknowledgment that Johnson deserved respect as an intellectual equal.

The story resonated especially powerfully in Harlem, where it became a source of pride and validation.

Here was proof, witnessed by 50 people including top Italian mobsters, that Black intelligence was equal to white intelligence. Proof that Harlem operators could compete strategically with the most powerful white criminals in America. Proof that respect could be earned through demonstrated capability rather than demanded through violence alone.

Five days after the first game, on September 25th, 1935, Johnson received a message from Luciano through intermediaries.

“Mr. Luciano requests another game. Friday evening, same place, same time,” the message read. “He says he studied the Sicilian Defense and wants a rematch. He also wants to discuss potential business cooperation after the game, if Mr. Johnson is interested.”

Johnson accepted immediately. He understood what the rematch request meant. Luciano wasn’t satisfied with being beaten once and leaving their relationship at that. He wanted to test himself again, to see if he could adapt to Johnson’s style, to continue the intellectual rivalry the first game had sparked.

The second game took place on Friday, September 27th, 1935, at the Exclusive Club.

This time there were fewer witnesses—only about 20, 10 from each side—because both men wanted less spectacle and more genuine competition. The second game lasted much longer than the first: 45 minutes instead of six.

The play was more cautious on both sides. Luciano had clearly studied the Sicilian Defense in the intervening week, learning to respond more effectively and avoiding the overconfidence that had doomed him in the first game.

But Johnson won again—this time with a completely different approach.

Where the first game had been decided by a brilliant tactical blow, the second was a masterclass in strategic patience. Johnson gradually accumulated small advantages, giving Luciano no chance to create complications or counterplay.

Move by move, he tightened the noose. Eventually, Luciano’s position became impossible to defend, and resignation was the only reasonable option.

After the game, Luciano said something that would define their relationship going forward. “Bumpy, you’re not just good at chess,” he told him. “You’re good at strategic thinking in general.”

“You won the first game through brilliant tactics—that queen sacrifice that trapped my rook,” Luciano continued. “You won this game through patient strategy, slowly building advantages I couldn’t counter.

“That versatility—being able to win in different ways depending on what the situation requires—that’s the mark of true intelligence. You think like someone who should be running major operations, not just enforcing someone else’s. And I respect that more than I can express.”

Then Luciano made a proposal that surprised everyone listening.

“Bumpy,” he said, “I’d like to meet with you regularly to play chess. Not as adversaries testing each other, but as two people who enjoy strategic thinking and can learn from competing against each other. Maybe once a month—sometimes in Harlem, sometimes in my territory. Just chess and conversation about how we both operate, how we both think about the business.

“No negotiations, no pressure, no hidden agenda—just two strategists enjoying intellectual competition. What do you say?”

Johnson agreed immediately.

He understood that Luciano was offering something valuable: ongoing contact that would allow them to build genuine mutual understanding, a relationship based on respect for intelligence rather than power dynamics or racial lines.

**The monthly chess games: building a friendship (late 1935–early 1936).**

From October 1935 through mid‑1936, Lucky Luciano and Bumpy Johnson met approximately once a month to play chess. Sometimes they met at the Exclusive Club in Harlem. Sometimes at Italian restaurants or social clubs in Little Italy. Occasionally at neutral locations elsewhere in Manhattan.

They always played with only a few trusted associates present—people who understood that these games were important both symbolically and practically. The ongoing matches signaled to New York’s underworld that peace existed between the Italian families and Harlem operators.

The games themselves varied in length and result. Johnson won most of them—probably around 70%. Luciano, however, did win occasionally, which kept the competition interesting for both men.

Sometimes the games were quick tactical battles decided by brilliant combinations. Other times, they were long strategic struggles lasting two or three hours before one player forced resignation.

Yet more important than the wins and losses were the conversations between moves—the discussions about operations, strategy, and psychology that unfolded over the board.

Luciano would ask Johnson’s opinion about problems he faced: how to deal with a difficult operator, how to structure a mutually beneficial deal, how to respond to law enforcement pressure without escalating conflict.

Johnson gave thoughtful advice, analyzing situations like chess positions—identifying weaknesses, suggesting strategies, predicting how different players would respond to various approaches.

Luciano treated those chess sessions like strategy consultations. As Theodore Greene later recalled, “He’d present Bumpy with problems he was facing, and Bumpy would analyze them like they were positions on the board. Lucky would actually implement some of Bumpy’s suggestions—and he’d credit Bumpy when those strategies worked.”

It was remarkable watching their relationship evolve—from Luciano testing whether Bumpy deserved respect, to Luciano genuinely valuing Bumpy’s strategic thinking and actively seeking it out.

The chess games became famous throughout New York’s underworld.

When people heard, “Lucky and Bumpy are playing chess tonight,” they understood it meant several things at once. It meant the peace between the Italian families and Harlem operators remained intact. It meant cooperation continued to benefit both sides. It meant Harlem’s independence remained secure.

Those games, one observer noted, were diplomacy. As long as Lucky and Bumpy were playing chess together, there was peace.

Young criminals on both sides—Italian and Black—watched those games and learned that intelligence mattered more than race. Respect earned through capability proved more valuable than fear imposed through violence.

**October 1935: the Dutch Schultz problem.**

While Luciano and Johnson were beginning their monthly chess sessions, Dutch Schultz remained a major problem for everyone in New York’s underworld. Schultz had spent years trying to violently take over Harlem’s policy operations, using extreme brutality against operators, killing those who refused to surrender, terrorizing entire communities, and refusing to negotiate.

Luciano had already decided that Schultz needed to be eliminated—not because he cared about Harlem operators specifically, but because Schultz’s tactics were drawing far too much law enforcement attention. Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey was building cases against multiple mob bosses, and Schultz’s violence made Dewey’s job easier by creating public pressure.

Still, Luciano needed to understand Harlem’s situation fully before acting.

He needed to know what would happen in Harlem after Schultz was gone. Would independent operators maintain peaceful control, or would his elimination create a power vacuum and chaos that might attract even more law enforcement scrutiny?

On October 15th, 1935, Luciano invited Johnson to dinner at an Italian restaurant in Midtown Manhattan. They ate, talked casually, and then played chess. Johnson won in 22 minutes, using another queen sacrifice that Luciano fell into despite having seen such tactics before.

After the game, Luciano got directly to the point.

“Bumpy, I want your honest strategic assessment of a situation,” Luciano said. “Dutch Schultz is a problem for everyone—for Harlem operators he terrorizes, for my operations because his violence attracts law enforcement, and for the entire Commission because he refuses to follow the rules we’ve established about limiting violence.

“I’m going to the Commission next week to get approval to eliminate Schultz. He’s become too dangerous to leave alive. But before I do that, I need to understand what happens to Harlem after he’s gone. Tell me honestly: can you and Stephanie control Harlem’s policy operations peacefully, or will his elimination create chaos?”

Johnson appreciated Luciano’s directness and answered just as bluntly.

“If Schultz disappears, Harlem becomes peaceful within a week,” Johnson said. “The independent operators can go back to running their policy games without terror. Stephanie is respected throughout Harlem. She’s seen as someone who stood up to Schultz when others surrendered. People will follow her leadership.”

“I can handle enforcement and security without excessive violence, because most operators will cooperate voluntarily once Schultz’s terror ends. The community will support independent Black operators over any white mobsters trying to fill Schultz’s place. Give us autonomy over policy gambling, respect our independence, and Harlem will be peaceful and profitable within days of Schultz’s elimination.”

Luciano nodded, studying Johnson’s face to judge whether this was realistic or wishful thinking.

“And if I give you that autonomy,” Luciano asked, “if I tell the Commission Harlem’s policy operations stay under independent Black control after Schultz is eliminated, you’re confident there won’t be fighting among Harlem operators? You’re confident you can maintain peace without my organization stepping in?”

“I’m confident,” Johnson replied without hesitation. “Stephanie and I have been preparing for Schultz’s removal for months. We know which operators will cooperate and which might cause problems. We have strategies to handle disputes without violence—to maintain peace through negotiation and mediation, not terror.”

“We’re ready to take full control the moment Schultz is gone,” Johnson added. “And we’ll keep that control peacefully, because that’s what Harlem wants and what we can deliver.”

Luciano smiled and extended his hand. “That’s exactly what I wanted to hear,” he said. “Because I’m going to the Commission meeting next week to get approval to eliminate Dutch Schultz. And I’m going to tell them that after Schultz is gone, Harlem’s policy operations belong to Stephanie St. Clair and Bumpy Johnson under complete autonomy.”

“My organization won’t interfere, won’t demand tribute, won’t pressure you to surrender or operate by our rules. You run Harlem your way, according to what works for your community. In exchange, we cooperate on certain opportunities where cooperation benefits both of us. Does that sound fair?”

Johnson shook Luciano’s hand firmly. “That sounds more than fair,” he said. “You have my word: Harlem will be peaceful and professional after Schultz is gone. We won’t create problems that attract law enforcement. We won’t start fights with Italian families over territory. We’ll keep our operations inside Harlem and run them in ways that generate profit without the chaos Schultz created.”

They shook on the agreement and then continued playing chess for another two hours, discussing the details of post‑Schultz Harlem: how disputes would be resolved, how cooperation between Harlem and the Italian families would work when interests overlapped.

**October 23rd, 1935: Schultz is eliminated.**

On October 23rd, 1935, Dutch Schultz was shot at the Palace Chop House in Newark, New Jersey, by assassins working for the Commission. He died the next day from his wounds, removing a man whose violence had endangered everyone’s operations for years.

The murder was approved by Luciano and the other Commission members because Schultz had become too violent, too unpredictable, and too much of a liability. His elimination was necessary for the stability of organized crime in New York.

Within hours of Schultz’s death, word reached Harlem that the terror was over.

Schultz’s organization collapsed almost instantly. His enforcers scattered or switched allegiance. His businesses were absorbed by other groups. His brutal campaign against Harlem’s operators ended as abruptly as it had begun.

Just as Luciano and Johnson had agreed three weeks earlier, Harlem’s policy operations remained under the complete control of Stephanie St. Clair and Bumpy Johnson. Luciano’s organization made no attempt to take over, demanded no tribute, and applied no pressure to force Harlem under Italian rules.

True to his word, Luciano gave Harlem full freedom to run its own operations, respecting the agreement based on mutual respect and strategic trust.

Within a week of Schultz’s death, Harlem’s policy gambling operations had stabilized under St. Clair and Johnson’s leadership. Operators who had been terrorized by Schultz returned to normal business.

The violence and chaos that had defined Schultz’s reign vanished. Harlem residents celebrated the return of relative peace, aware that their freedom had been secured partly through Bumpy Johnson’s intelligence. It was the same intelligence that had beaten Lucky Luciano at chess in six minutes—and turned that victory into operational autonomy for an entire community.

**1936–1940: the golden age of Harlem independence.**

From late 1935 through 1940, Harlem experienced what many called a golden age of independent Black criminal operations—made possible largely by Lucky Luciano’s respect for Bumpy Johnson’s intelligence.

Stephanie St. Clair and Bumpy Johnson controlled Harlem’s policy gambling operations with complete autonomy. They ran professional, relatively nonviolent enterprises that generated millions of dollars while maintaining broad community support.

They employed hundreds of Harlem residents, funded legitimate businesses, supported local initiatives, and proved that Black operators could run successful enterprises without white supervision or control.

Luciano and Johnson continued playing chess regularly throughout this period—sometimes twice a month, sometimes once every six weeks, depending on schedules and circumstances.

The games remained part intellectual competition, part friendship maintenance, part diplomatic signal that peace between Italian families and Harlem operators remained strong.

Lucky genuinely enjoyed those sessions. One of his closest associates later recalled, “He’d look forward to them like other people look forward to social events. He’d study chess strategy between games, trying to develop tactics that might beat Bumpy. He’d be genuinely excited when he actually won, which happened occasionally—but not often.”

More than the competitive thrill, Luciano valued the conversations. He used the games to talk through strategic problems, to test ideas against Johnson’s intelligence, to seek advice when Bumpy’s perspective might reveal angles he’d missed.

He treated Johnson like a trusted adviser—like a partner in thinking about New York’s criminal ecosystem. That relationship was valuable to Lucky both practically and personally.

Their friendship became so well‑known that other Italian mobsters began treating Harlem’s operators with greater respect. If Lucky Luciano, the most powerful mob boss in America, treated Bumpy Johnson as an intellectual equal and gave Harlem operational autonomy, then other Italian families had to honor that relationship.

The chess games became powerful symbols. Theodore Greene explained: “When people in the underworld heard that Lucky and Bumpy had played chess again last night, it meant several things at once. It meant the peace was holding. It meant cooperation continued to benefit both sides. It meant Harlem’s independence remained secure.

“And it meant that intelligence and strategic thinking mattered more than race or ethnicity in determining who deserved respect.”

What began as a test—Lucky asking whether Bumpy was smart enough to deserve respect—evolved into the foundation of the most successful cooperation between Italian mobs and Black operators New York had ever seen.

**The friendship deepens beyond business.**

By late 1936 and into 1937, the relationship between Luciano and Johnson evolved beyond business cooperation into something approaching genuine friendship, built on mutual respect and shared love of strategy.

Sometimes they met just to play chess without discussing business at all—pure games played for the intellectual challenge and the pleasure of competing against an equal. Those games often lasted longer, because neither man was in a hurry to end them.

They began exchanging books on strategy, military history, and philosophy.

Luciano sent Johnson a leather‑bound copy of Sun Tzu’s *The Art of War*, inscribed in his own hand: *“To Bumpy, the most strategic mind I’ve encountered in 20 years of criminal operations. Your friend, Lucky.”*

Johnson responded weeks later with a rare edition of Machiavelli’s *The Prince*, inscribed: *“To Lucky, who understands that intelligence transcends all boundaries. With respect, Bumpy.”*

They debated these books during their games, discussing which principles applied to criminal operations and which were outdated or ill‑suited to modern realities.

Those conversations revealed both men to be more intellectually sophisticated than their public reputations suggested. They weren’t just criminals who understood violence and intimidation. They were strategic thinkers who studied history and philosophy and applied those lessons to their world.

“It was remarkable watching their friendship develop,” one observer said. “Here were two men from completely different backgrounds. Lucky was Sicilian, the child of immigrants, who built his power through Italian organizations and brutal gang wars. Bumpy was Black, born in South Carolina, shaped by Harlem’s culture and the realities of Black communities.”

“They should have been enemies, according to 1930s America. Instead, they were friends—genuine friends who respected each other’s intelligence and enjoyed competing intellectually. Strategic thinking created stronger bonds than race or ethnicity.”

**June 1936: Luciano’s arrest and the final game.**

On June 1st, 1936, Lucky Luciano was arrested by New York City police on compulsory prostitution charges brought by prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey. It marked the beginning of the end of Luciano’s direct control over New York’s underworld. He was convicted later that month and sentenced to 30–50 years in prison.

Before surrendering to begin his sentence, Luciano requested one final chess game with Johnson. The game was set for the evening of June 5th, 1936, at the Exclusive Club in Harlem—the same place where their first legendary game had been played nine months earlier.

The atmosphere this time was completely different.

The first game had been a test: Luciano challenging Johnson to prove his intelligence. This last game was a farewell between friends who had developed deep mutual respect through nine months of regular games and strategic conversation.

They played for 90 minutes—the longest game they had ever played together. The competition was fierce but friendly. Both men played at the highest level they could, each demonstrating how much they’d improved through constant competition.

The game ended with Johnson winning by a very narrow margin after a complex endgame that could have gone either way.

After the game, Luciano said something that perfectly captured what their relationship had meant.

“Bumpy, I’m going away for a long time,” he said. “Probably for the rest of my life. Dewey’s charges are serious and the political pressure to convict me is enormous.

“But I want you to know that these past nine months—these chess games, these conversations about strategy, learning to respect your intelligence and to value your friendship—these have been some of the best experiences of my career. You taught me something important that I should have known already, but didn’t truly understand until I met you.”

“That intelligence exists everywhere,” Luciano continued. “That the smartest people aren’t always the most powerful, or the most established, or the same race as you. And that respecting intelligence—wherever you find it—makes you stronger, not weaker. That’s a lesson I’ll take with me to prison. And it’s a lesson I hope everyone in New York’s underworld learns from watching our relationship.”

Johnson replied with equal sincerity.

“Lucky, you gave Harlem something no one else ever gave us,” he said. “Freedom to run our own operations without outside interference, without surrendering to more powerful organizations, without constant violence and pressure.”

“You did that because you valued intelligence over race,” Johnson went on. “Because you saw that cooperation based on mutual respect was smarter than conquest based on power. That’s wisdom most people never learn—and it benefited everyone.

“I’ll always respect you for that. And I’ll always remember you as someone who proved that intelligence and friendship can transcend all the divisions that are supposed to keep people apart.”

They shook hands firmly. The next morning, Luciano left for prison.

**1936–1945: the legacy continues.**

Even after Luciano went to prison in June 1936, the agreements he had made with Bumpy Johnson remained in force. The Italian mob families who took over various parts of New York’s criminal underworld honored Luciano’s commitment to leave Harlem’s policy operations under independent Black control.

This was not because of written contracts—criminal organizations don’t work that way. It was because Luciano’s respect for Johnson had been public, emphatic, and undeniable.

Nine months of regular chess games, witnessed by many, had made their relationship and agreements part of underworld lore.

Other mob bosses understood that challenging Harlem’s independence would mean disrespecting Luciano’s judgment and wisdom—suggesting he had been wrong to respect Johnson. Few were willing to do that, partly out of genuine respect for Luciano, partly because he still wielded influence from prison, and partly because the arrangement was working and changing it would create problems without clear benefit.

Harlem maintained its autonomy throughout the late 1930s and into the 1940s, running successful policy operations that generated millions while avoiding the kind of violence that drew intense law enforcement attention.

Johnson continued visiting Luciano in prison when possible, bringing chess sets, playing in the visiting room, and maintaining the friendship they had built.

Prison rules limited how often and how long they could meet, but they stayed in contact. The relationship that began with a six‑minute game in September 1935 continued, against all odds, behind prison walls.

Their friendship became legendary in criminal circles: the story of how a six‑minute chess game had created respect between two men who should have been enemies, and how that respect had given an entire community freedom from outside control.

“The story of Lucky and Bumpy’s chess games became one of the most famous legends in New York criminal history,” Greene reflected years later. “Not because of the games alone—though those were remarkable—but because of what they represented.”

“They represented the idea that intelligence transcends race and background. That respecting capability creates stronger partnerships than demanding submission. That friendship based on mutual respect for strategic thinking can overcome all the divisions society uses to keep people separated.”

That legend inspired people in criminal circles and beyond. It showed young Black people that intelligence could be respected—even by powerful white criminals—when it was demonstrated clearly. It proved that six minutes of chess in 1935 had consequences that would echo for decades.

**Epilogue: the power of six minutes and mutual respect.**

Lucky Luciano spent nine years in prison before being released in 1946, reportedly as a reward for assisting the U.S. government during World War II. He was immediately deported to Italy, where he lived in exile until his death in 1962, never returning to America, though still exerting influence over organized crime through trusted associates.

Bumpy Johnson continued controlling Harlem’s criminal operations until his own imprisonment in 1952, maintaining the independence Luciano’s respect had secured. Johnson was released in 1963 and resumed control in Harlem until his death from a heart attack in 1968.

In their later years, both men would occasionally talk about the chess games they’d played in 1935–1936.

Luciano would tell other prisoners and associates about “the time a Black man from Harlem beat me at chess in six minutes using the Sicilian Defense and taught me that intelligence doesn’t care about race.”

Johnson would tell younger operators how playing chess with Lucky Luciano had earned Harlem its freedom and proved that respect based on demonstrated capability mattered more than power based on violence.

The phrase “I don’t play to lose,” spoken by Johnson after that first six‑minute victory, became legendary—not just in criminal circles but in American culture more broadly.

It was quoted in prisons, in sports, in business, in education—anywhere people faced challenges and needed to adopt a mindset that valued preparation and strategy over hope and luck.

But perhaps more important than that famous phrase was the lesson both men learned from their unlikely friendship: that when you value intelligence above all else, when you respect capability wherever you find it, when you judge people by their strategic thinking rather than by race, background, or status, you don’t just become more powerful—you become wiser.

You build relationships that transcend the artificial divisions society uses to keep people separated and competing unnecessarily.

Six minutes of chess on September 20th, 1935. Nine months of regular games and deepening friendship. A partnership that gave a community its freedom and proved that respect for intelligence could overcome racism.

A legend that has lasted more than 80 years and continues to inspire people facing challenges in any competitive arena.

That was the power of the chess game that changed everything—not just because of brilliant tactics or perfect strategy, but because it created mutual respect that transformed enemies into friends.

And it proved that *“I don’t play to lose”* was more than a line.

It was a philosophy which, combined with genuine respect for others’ intelligence, could change communities, relationships, and lives.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load