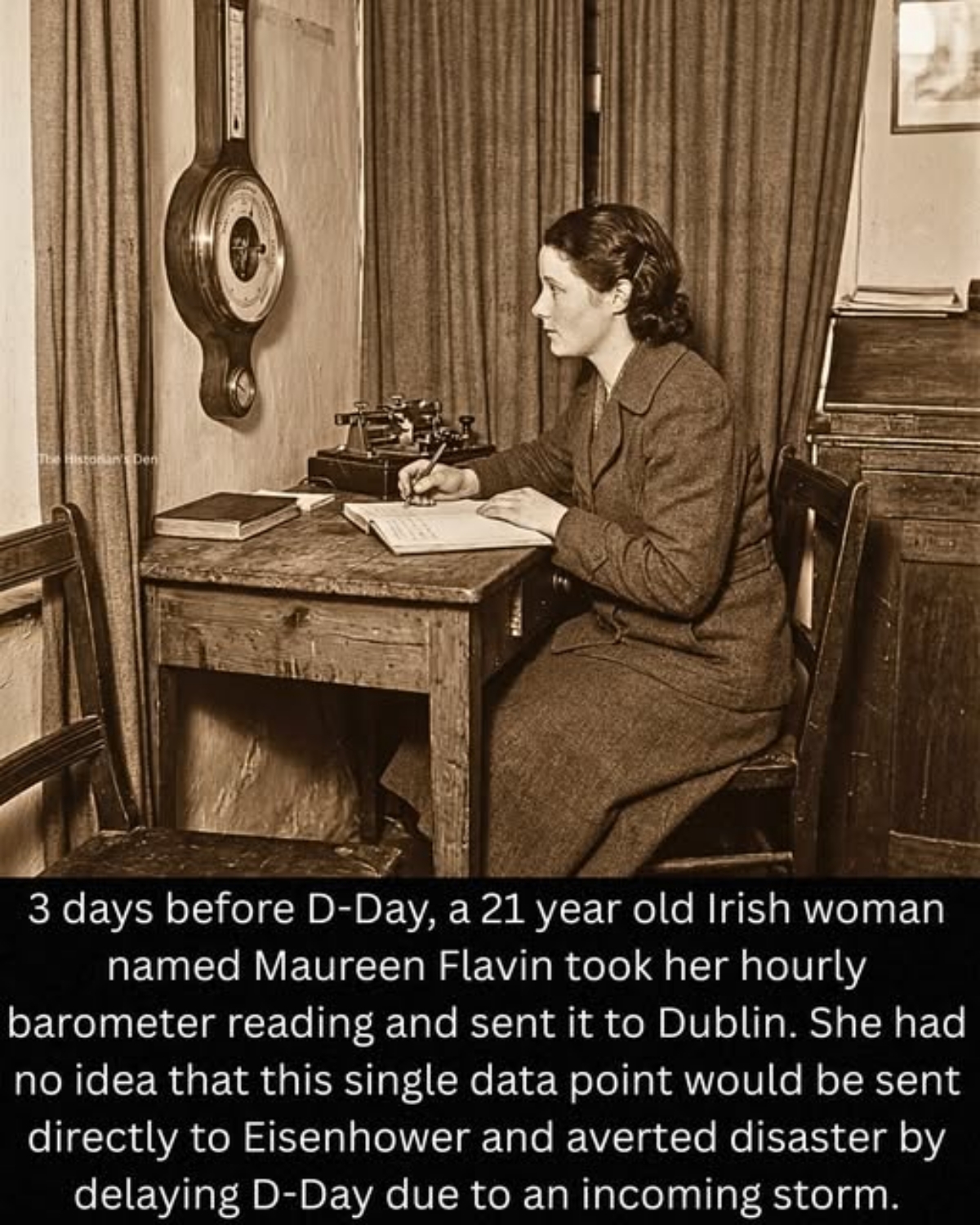

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done hundreds of times.

She picked up a barometer, read the needle, wrote down a number—and quietly nudged the course of World War II.

She didn’t know it, of course.

To her, it was just another hour, another reading, another entry in a logbook no one seemed to care about except a few people in Dublin.

Her name was Maureen Flavin.

—

## A lonely post at the end of the map

In the spring of 1944, Blacksod Bay wasn’t the kind of place anyone would associate with global decisions and world leaders.

Perched on the rugged coast of County Mayo, on Ireland’s western edge, it felt like the end of the world. The Atlantic was the only thing beyond it—cold, gray, and relentless.

The weather station itself was small and unglamorous. A few rooms. Some instruments. Peeling paint. The constant rattle of wind.

Inside, the equipment was familiar: a barometer, a thermometer, wind gauges, stacks of paper, and logbooks that had to be filled out with absolute precision, hour after hour, day after day.

From the outside, it looked like nowhere.

From the air, to a pilot crossing the Atlantic, it was just a dot.

But on the war maps of Allied planners, remote stations like Blacksod Bay were precious: tiny eyes on a huge, unpredictable ocean.

Maureen’s job was simple, at least on paper.

Observe. Record. Report.

Every hour, she would step out, feel the bite of the wind on her face, check the instruments, and write down the readings. Then she would send them along the chain—to Dublin, as Ireland was neutral in the war, and from there, on to the Allied meteorologists watching the Atlantic like hawks.

It was repetitive work. It demanded patience. It demanded *accuracy*.

No one cheered when she did it right. But if she did it wrong, the consequences could be enormous, even if she never saw them.

—

## A world waiting, and not knowing

By late May and early June 1944, the Allied command was holding its breath.

D‑Day—the long‑planned invasion of Nazi‑occupied France—was almost ready to begin.

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were waiting in camps across southern England. Ships were gathering in ports. Planes stood fueled on runways. Tanks and trucks were lined up, loaded onto landing craft.

The scale was staggering. It would be the largest amphibious invasion in history.

But there was one thing no general, no matter how powerful, could command: the weather.

To launch the invasion, they needed a specific, narrow set of conditions.

They needed:

– A low tide, so obstacles on the beaches would be exposed.

– A rising sun, so pilots could see their targets.

– A full moon the night before, to give light to airborne troops dropped behind enemy lines.

– And, crucially, seas calm enough and skies clear enough to send ships, planes, and thousands of men across the English Channel without turning the operation into a massacre.

All of that together meant that only a few days in early June would work.

If they missed that window, they would have to wait weeks for the next chance. Every day they waited, the risk of leaks grew. German defenses might strengthen. Troops might lose their edge, morale might dip.

The commanders knew it: there would not be many opportunities to try this. And failure could not just cost thousands of lives—it could prolong the war by years.

So they watched the skies. They listened to reports. They studied charts.

And far away, on a storm‑beaten Irish coast, a 21‑year‑old was walking over to a barometer.

—

## A subtle drop

It was June 3, 1944.

To Maureen, it was just another day on duty.

Outside, the Atlantic was doing what it always did: shifting moods, stacking clouds on the horizon, sending gusts one moment and silence the next. To most people, the weather might have seemed “typically Irish”—changeable, gray, nothing special.

But weather observers learn to see what others miss.

When Maureen checked the barometer, the reading was a little lower than it should have been. Not dramatically. Not in a way that shouted *storm*. Just… off. A subtle drop, but unmistakable for someone who stared at those needles and numbers every day.

For many, it would have been easy to shrug. Instruments can lag. Conditions fluctuate.

But the discipline drilled into her was clear: you don’t edit the weather. You don’t “round” reality. You write what you see.

So she did.

She noted the pressure. Logged the time. Sent the report on schedule.

There were no trumpets when she did this. No sense that anything extraordinary had happened.

Just the click of the pen, the scratch of paper, the hum of routine.

But beyond Ireland, men were staring at maps, frustrated.

—

## In the war rooms: confusion, fear, and doubt

Allied meteorologists in Britain were under crushing pressure.

Models in 1944 were primitive by today’s standards. There were no satellites, no modern supercomputers, no radar sweeping every cloud. Forecasting the weather meant piecing together scattered observations, ship reports, coastal stations—then trying to guess what the invisible atmosphere hundreds of miles away was about to do.

Over the North Atlantic, the data was especially thin.

And yet, that was precisely where the weather that would shape D‑Day was being born.

The meteorologists had a problem. Their existing readings suggested something troubling: the possibility of a deep low‑pressure system brewing—code for stormy conditions. But they lacked solid confirmation from the western Atlantic region. It was like seeing shadows move behind a curtain and trying to guess whether it was a man, a dog, or just the wind.

One wrong call, and they would either:

– Launch the invasion into a storm that could drown soldiers and wreck ships.

or

– Delay an invasion that could have succeeded, losing precious time and possibly the element of surprise.

Maureen’s report from Blacksod Bay arrived in this tense atmosphere.

Her reading, small as it was, fit the pattern the meteorologists feared: pressure was falling, and not by accident.

This was the clue they needed. A piece of the puzzle, quietly delivered from a remote Irish bay.

The storm was real—and it was coming.

—

## The message climbs the chain

From Dublin, the Blacksod Bay report moved into Allied hands.

From Allied meteorologists, it moved higher.

Now it wasn’t just numbers on a log sheet. It was a warning.

The forecasters put the data into their evolving mental models. Other reports came in, and together they painted a clearer picture: a powerful Atlantic storm was forming to the west and was set to slam into the British Isles and the Channel just as the planned invasion date approached.

If the landings went ahead in the teeth of that storm, the result could be devastating:

– Landing craft unable to approach the beaches safely.

– Troops seasick, disoriented, and soaked before they even saw enemy fire.

– Air support grounded or wildly inaccurate.

– Paratroopers scattered, lost, or killed by winds.

The English Channel—a necessary pathway—would become a graveyard.

The meteorologists knew what this meant. They were about to tell the supreme commander of Allied forces that the invasion, which had taken years to plan, might need to be delayed because of conditions no one could control.

And at the root of that warning was a tiny signal from a remote Irish barometer, recorded by a woman who had no idea her numbers were about to land on Dwight D. Eisenhower’s desk.

—

## Eisenhower’s impossible choice

Imagine the room.

It’s June 4, 1944. The invasion is scheduled for June 5.

The weather looks bad. Reports are mixed. Some say the storm might hold off. Others say it’s already brewing. No one can give a 100% guarantee. No one ever can.

Outside, in camps and ports across southern England, tens of thousands of men are ready. Tanks are fueled. Warships are in motion. Air crews are briefed.

The machine of war is humming and straining at the leash.

Inside, Eisenhower listens as his meteorologists lay out the facts. Among the data: the Atlantic low‑pressure system, the falling barometric readings—including those from the west coast of Ireland.

The message is brutally simple:

If you launch on June 5, you may be sending men into chaos.

But there is a narrow hope.

The meteorologists see a small break in the storm system—a brief window of improved weather expected around June 6. It won’t be perfect, but it may be just good enough.

The choice Eisenhower faces is almost unbearable:

– Stick to the original schedule, ignore the worst‑case forecast, and risk disaster.

– Or delay the invasion, with all the risks—logistical, psychological, strategic—that delay brings.

He walks out. He thinks. He comes back.

Commanders argue. Some push for going ahead. Others warn against it. They know that weather forecasts are uncertain. They know men might die either way—on the beaches or in the months of war that might follow a postponement.

But Eisenhower must decide.

In the end, he makes the call:

Postpone.

The invasion is delayed 24 hours. The gamble shifts from *hoping the storm will not come* to *hoping the break will arrive in time*. The entire Allied effort pivots around that narrow gap.

And he makes that decision, in part, because of a thin thread of information that started in a tiny weather station on the edge of Ireland, when a 21‑year‑old looked at a barometer and chose to trust what she saw.

—

## The window opens

The storm comes.

On June 5, the seas would have been brutal. Winds howled. Rain lashed. The Channel seethed.

It was the kind of weather that could swamp landing craft, ground aircraft, and strip away what little control commanders had once the operation began.

The men who had slept in their gear, ready to go, were told to stand down and wait. Confusion. Frustration. Rumors. Soldiers had no idea that a storm out in the Atlantic—and a decision taken in a room they’d never see—had just kept them alive.

But just as the meteorologists had predicted, the weather began to ease.

June 6, 1944.

The seas were still rough, the skies still imperfect—but they were manageable. Risky, but not suicidal. Enough to try.

That morning, Allied ships crossed the Channel. Planes roared overhead. Landing craft slammed into the surf. Men ran onto beaches laced with mines, wire, and machine‑gun fire.

They called it D‑Day.

The success of the landings—painful, bloody, and far from guaranteed even with decent weather—was built on many foundations: strategy, intelligence, deception operations, logistics, courage.

But it also rested quietly on something more humble: the accuracy of a weather forecast, and the reliability of the observations that fed it.

—

## In Blacksod Bay, life goes on

While the world remembers the thunder of guns on Omaha Beach and the paratroopers dropping into Normandy, Blacksod Bay that day looked very much the same as it had the week before.

The wind still blew. The clouds still rolled in from the Atlantic. The sea still crashed against the rocks.

Inside the weather station, the routine continued.

Check the instruments.

Read the numbers.

Record the data.

Send the report.

It’s likely that Maureen had no idea, as the days passed, exactly how much weight had rested on her observations. She knew, generally, that the war depended on forecasts. She knew that information flowed from small stations to big decisions. But the specific impact of that particular falling barometer reading? That would only become clear decades later, when stories were told and reports studied.

At the time, she was just doing her job—quietly, thoroughly, without fanfare.

—

## The weight of a “small” job

There’s something deeply moving about that.

We tend to tell history through the lives of generals and presidents, dictators and revolutionaries. We talk about Eisenhower and Churchill, Hitler and Stalin. We picture big tables covered in maps, dramatic speeches, famous faces.

But wars are not decided by big men alone.

They are shaped by countless small, consistent actions taken by people whose names rarely make it into the textbooks.

A barometer reading in a tiny Irish station.

A radio operator not missing a transmission.

A clerk copying a report correctly instead of rounding the numbers.

A meteorologist in some dimly lit room trusting those numbers, even when they’re just one tiny data point among hundreds.

Maureen’s story is a reminder that the “little” jobs are rarely little at all.

They are threads in a much bigger fabric—and sometimes, when the world is under pressure, one thin thread can hold more weight than anyone imagines.

—

## Courage in quiet precision

Maureen didn’t charge a machine‑gun nest or storm a beach.

She didn’t brief generals or address parliaments.

Her courage looked different.

It was the courage to be meticulous when no one was watching.

To resist the temptation to be “approximate” when something looked odd.

To respect the process, even when it felt repetitive.

In peacetime, that’s professionalism.

In wartime, that can be a form of heroism.

Think about the alternative: a slightly careless reading. A number adjusted because “it’s probably just a blip.” A log entry that smoothed over the strange drop in pressure.

If enough people had done that, the storm might never have been properly seen until it was too late.

Instead, someone in Blacksod Bay—the young Irish observer who thought she was just doing routine work—did the boring thing *perfectly*. And that boring thing turned out to be crucial.

—

## The human side of a number

It’s easy to see weather as abstract—lines on a chart, colored blobs on a map, arrows and numbers. But behind every data point is a human being: tired, cold, perhaps lonely, getting on with their shift.

Picture Maureen that day:

– Standing in the doorway, squinting into the Atlantic wind.

– Feeling that damp chill that seeps into your bones.

– Coming back inside, rubbing her hands, maybe wrapping them around a warm cup of tea.

– Opening the logbook.

– Looking at the barometer once more, just to be sure.

– Writing the number down carefully.

– Checking her arithmetic.

– Transmitting the report.

No audience. No applause. No dramatic music.

Just the steady hum of responsibility—and the sense that, whatever was happening out there in the wide, burning world, she could at least do *this* right.

—

## The legacy of one reading

D‑Day succeeded at an enormous cost, but it did succeed. The Allies established a foothold in France. From there, the long push toward Germany continued. Less than a year later, the war in Europe was over.

Would all of that have failed without that weather delay?

No one can say with absolute certainty. History doesn’t give us clean control experiments. But military historians and meteorologists alike agree on one thing: launching the invasion just one day earlier, in that storm, could have been catastrophic.

In that sense, Maureen Flavin’s barometer reading is one of the most consequential weather observations ever recorded. It didn’t win the war by itself—but it helped make sure the crucial first step of the final phase wasn’t taken at the worst possible moment.

And for decades, the world barely knew her name.

—

## What her story tells us today

There’s something quietly powerful about the idea that a young woman in a neutral country, working in a remote station, could influence the fate of millions without even realizing it.

It challenges some easy assumptions:

– That only dramatic acts matter.

– That only people in obvious positions of power shape history.

– That if we’re not on the front line, our efforts are somehow “less important.”

Maureen’s story suggests the opposite.

The world relies on people who take care in small things. Who show up for their shifts. Who write down the right number even when it barely moves the needle—literally.

On June 3, 1944, she was just doing her job.

On June 4, Eisenhower made a decision that hinged, in part, on her work.

On June 6, thousands of soldiers pushed forward under skies that might have been far worse.

And over the decades that followed, historians slowly realized that one of the many invisible threads holding that decision together began in a windswept bay in western Ireland.

—

## A quiet place in history

When we think of D‑Day, we picture beaches, cliffs, bunkers, and waves of men pushing through fire and steel.

It’s right that we remember their courage.

But maybe, alongside those images, we can also hold another:

A young woman in a plain room, listening to the wind outside, bending over a barometer, and carefully writing down what she sees.

No drama. No spotlight. Just precision.

Three days before D‑Day, Maureen Flavin thought she was carrying out a routine task.

In reality, she was placing a small but vital piece into a vast, fragile puzzle.

Her diligence helped ensure that when history knocked, the Allies met it on a day when the seas, skies, and winds—just barely—allowed them a fighting chance.

Sometimes, doing the small thing well is the biggest contribution we’ll ever make.

She probably never imagined that.

But history remembers it—even if only as a single line in a long story, written, appropriately, in very careful numbers.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

SH0CKING FBI CONFESSION: Behind Baby Grace’s Death

October 29th, 2007, 10:30 p.m. Robert “Rob” Spin is out on Galveston Bay fishing for flounder when the wind suddenly…

End of content

No more pages to load