June 8th, 1962.

2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem.

May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue when Vincent “Vinnie Slick” Teranova stepped in front of her. Vinnie was a Genovese soldier, 34 years old, with a reputation for collecting debts and intimidating witnesses. He’d been operating in Harlem for three weeks under orders to pressure local businesses into paying protection money to the family.

“You tell your husband,” Vinnie said, loud enough for the dozen people on the street to hear, “that this neighborhood don’t belong to him no more. It belongs to people who actually matter.” May didn’t respond. She tried to step around him.

Vinnie grabbed her arm. “I’m talking to you,” he said. May pulled her arm away. “Take your hands off me.” That’s when Vincent Teranova made the decision that would end his career and nearly destroy his family’s position in New York.

He slapped her.

Not a push, not a shove—an open‑handed slap across the face that echoed down 125th Street and stopped every conversation, every transaction, every movement within a 30‑foot radius.

May Johnson stood there for three seconds, her face red where his hand had connected, her grocery bag on the sidewalk. She stared at Vinnie with an expression that wasn’t fear or shock. It was pity.

Because May Johnson had been married to Bumpy for 17 years, and she knew exactly what was about to happen to the man standing in front of her. Vinnie didn’t understand what he’d just done. He thought he’d made a power move, sent a message, proven that the Genovese family could operate in Harlem without fear of consequences.

He was wrong about all of it.

Bumpy Johnson found out about the incident 11 minutes after it happened. He was in his office above Small’s Paradise when Julius Gordon walked in without knocking—something Julius only did when a situation required immediate attention.

“May,” Julius said. “125th and Lenox. Genovese soldier named Vincent Teranova. He put his hands on her.”

Bumpy looked up from the ledger he’d been reviewing. His expression didn’t change. “Is she hurt?”

“No, but he slapped her. In front of witnesses.” For ten seconds, Bumpy didn’t move. He just sat there, processing what Julius had said, running through calculations that had nothing to do with anger and everything to do with what came next.

“Where is she now?”

“Home. Illinois is with her. And Teranova’s still operating. He doesn’t know we know yet.”

Bumpy stood up slowly and walked to the window overlooking 135th Street. He watched the afternoon crowd moving through Harlem. People going about their business, living their lives, trusting that the neighborhood they called home was protected by someone who understood what that word meant.

“Get me everything on Teranova,” Bumpy said quietly. “Family connections. Where he lives. Who he works with. What he values most. I want to know everything by tonight.”

“What are you going to do?” Julius asked.

“I’m going to teach the Genovese family why some lines don’t get crossed.”

By 9:00 p.m. that night, Bumpy had a complete file on Vincent Teranova. Born in Brooklyn, 1928. Married to Angela Teranova. Two children, ages six and eight.

He lived in a house on President Street in Carroll Gardens. His father was deceased, but his mother, Rosa Teranova, lived three blocks away, and Vinnie visited her every Sunday after church.

Vinnie worked directly under Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo, a Genovese captain who controlled labor racketeering and loan‑sharking operations in Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan. Vinnie had been arrested twice, convicted once, and had served 18 months for extortion.

Most importantly, Vinnie was ambitious. He wanted to prove himself to the family. He wanted a promotion. He wanted to be seen as someone who could handle difficult territories like Harlem. That ambition had made him reckless, and reckless men made mistakes that couldn’t be taken back.

That night, Bumpy spent three hours doing something most people would never associate with a man planning retaliation. He made phone calls to people who had nothing to do with crime.

He called a jeweler in Midtown. He called a photographer in the Bronx. He called a woman who ran a boutique dress shop in SoHo. He called a printer who specialized in custom work.

To each of them, he gave very specific instructions.

What Bumpy understood—and what separated him from men like Vincent Teranova—was that violence is temporary, but awareness is permanent. Over the next three days, Bumpy orchestrated something that required more discipline than any shooting, more precision than any ambush.

He had Teranova’s entire life photographed without Teranova ever knowing he was being watched. A photographer sat in a car across from Rosa Teranova’s church, capturing her Sunday morning routine.

Another followed Angela to the grocery store, maintaining enough distance to remain invisible but close enough to document every movement. A third positioned himself near PS 58, photographing the exact moment Vinnie’s children arrived at school, the route they walked, the crossing guard who helped them across the street.

Each photograph was developed professionally, arranged chronologically, and placed in a leather album that cost $200—the kind of quality you’d use for wedding photos or family memories.

Bumpy reviewed every single image personally, making sure the message was unmistakable:

I see everything you love.

I know where they go.

I understand what matters to you, and I’ve been watching while you had no idea.

The album took 72 hours to complete. When Bumpy finally held the finished product in his hands, he knew that Vincent Teranova would open it and understand immediately that this wasn’t about revenge.

It was about showing a man that his entire world existed at Bumpy’s discretion. And that discretion was the only thing keeping it intact.

June 12th, 1962.

Four days after the incident, Vincent Teranova was having breakfast with his wife and children when someone knocked on his front door. It was 7:30 a.m., earlier than he usually got visitors, but Vinnie wasn’t concerned.

He told Angela to stay in the kitchen and went to answer it himself. A courier stood on his doorstep holding a package wrapped in brown paper.

“Vincent Teranova?” the courier asked.

“Yeah.”

“Delivery for you. Sign here.”

Vinnie signed, took the package, and closed the door. The package was roughly the size of a shoebox, not particularly heavy, with no return address. He brought it into his study and opened it.

Inside was a leather‑bound photo album.

Vinnie opened the album to the first page and went completely still. The first photograph showed his mother, Rosa, leaving church last Sunday. The photo was professionally taken, high‑quality, clearly shot from across the street.

Someone had been watching her.

The second photograph showed his wife, Angela, at the grocery store with their two children. The third showed their children’s school, PS 58, with a timestamp: 8:15 a.m.—the exact time they arrived each morning.

The fourth showed his house from three different angles.

Page after page, the album contained photographs of every person Vinnie cared about, every place they went, every routine they followed. His mother’s bridge club. His son’s baseball practice. His daughter’s piano lessons. His wife’s sister’s house, where the family gathered for Sunday dinner.

Someone had been watching all of them for days, maybe weeks, and documenting everything.

The final page of the album contained no photograph, just a handwritten note in elegant script:

*You put your hands on my wife in public. I could put my hands on everyone you love in private, but I won’t because I’m not you. This is the only warning you’ll receive. Leave Harlem today and never come back. If I see you in my neighborhood again, this album becomes an instruction manual instead of a warning.*

There was no signature. There didn’t need to be.

Vinnie’s hands were shaking so badly he dropped the album. He stood in his study for five minutes, thinking about his children walking to school, his mother leaving church, his wife at the grocery store.

All of them visible.

All of them vulnerable.

All of them photographed by someone who could have done anything at any time—and chose not to.

Because Bumpy Johnson wasn’t sending a threat. He was demonstrating capacity. The difference between *I could hurt you* and *I could have already hurt you and chose not to* is the difference between empty threats and absolute power.

At 8:15 a.m., Vinnie Teranova called Tony Ducks.

“I need to talk to you now.”

“What’s wrong?”

“I’m pulling out of Harlem.”

“You’re what?”

“I’m done. It’s over. I’m not going back.”

Tony was silent for a moment. “Come to the club. We’ll talk about this.”

June 12th, 1962.

11:00 a.m.

Vincent Teranova sat across from Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo in a social club in Greenwich Village and placed the photo album on the table.

“Open it,” Vinnie said.

Tony opened the album and went through it page by page, his expression darkening with each photograph. When he reached the final note, he closed the album and looked at Vinnie.

“Bumpy Johnson sent this.”

“Who else?”

“When?”

“This morning. Four days after I—”

“After you slapped his wife,” Tony said quietly.

“I didn’t know.”

“You didn’t *think*,” Tony interrupted. “You put your hands on a man’s wife in public without understanding who you were dealing with.”

“I was making a point.”

“You made a mistake.”

Tony pushed the album back across the table. “This isn’t a threat, Vinnie. This is a demonstration. He’s showing you that he could have killed your mother, your wife, your children—anyone he wanted at any time in the last four days. But he didn’t, because he’s giving you a chance to walk away.”

“So what do I do?”

Tony was quiet for a long moment. “You do exactly what he told you to do. You leave Harlem today and you never go back.”

“And if I don’t?”

Tony looked at Vinnie with something that might have been pity. “Then everyone in that album becomes a target. And Bumpy Johnson doesn’t make threats he isn’t prepared to follow through on. This isn’t about fear, Vinnie. This is about understanding that you crossed a line, and he’s giving you one chance to uncross it.”

Vinnie left the meeting at 11:30 a.m. By 2:00 p.m., he’d informed every business he’d been pressuring in Harlem that he was no longer operating in the area.

By 5:00 p.m., he was home, explaining to his wife that they needed to be more careful, more aware, more protected. And he never set foot in Harlem again.

But Vincent Teranova’s retreat wasn’t the end of the story.

The photo album made its way through the Genovese family’s leadership over the next week. Tony Ducks showed it to his boss, who showed it to Vito Genovese’s representatives, who discussed it in a meeting that included all five families.

The reaction wasn’t what Vinnie had expected. The families weren’t angry at Bumpy Johnson. They were angry at Vincent Teranova.

Because what Bumpy had done—sending a warning instead of retaliating with violence, demonstrating capacity instead of exercising it, giving Teranova a chance to retreat with his life and his family intact—that was the kind of move that made the families look weak if they responded with force. Bumpy had boxed them in perfectly.

If they came after him for threatening Teranova, they’d have to explain why they were protecting a soldier who’d put his hands on an unarmed woman in public. If they didn’t respond, they’d have to accept that Bumpy Johnson had set a boundary their own man had violated—and that Bumpy’s response had been more strategic and more effective than anything they could have done.

Either way, Bumpy won.

Within two weeks, the Genovese family issued a quiet directive. No operations in Harlem without explicit approval from family leadership. No soldiers were to engage with Bumpy Johnson or his associates without authorization.

And anyone who put their hands on civilians, especially women, especially in public, would answer to the family—not to Bumpy. It was the first time the five families had changed their operational guidelines because of one man’s response to one incident.

And it happened because Bumpy Johnson understood something that Vincent Teranova never would.

Power isn’t about how much damage you can do.

It’s about how much damage you choose *not* to do, and making sure everyone knows you made that choice.

June 8th, 1962, a mobster slapped Bumpy Johnson’s wife in public. Four days later, that mobster received a photo album that made him leave Harlem forever.

Two weeks later, the entire Genovese family changed their operating procedures. And for the rest of his life, Vincent Teranova would wake up sometimes in the middle of the night thinking about those photographs.

Thinking about how close he’d come to losing everything that mattered. Thinking about the fact that Bumpy Johnson had held his family’s lives in his hands—and chosen to let them go.

Not because Bumpy was weak.

Because Bumpy was strong enough to know that the most powerful thing you can do to someone isn’t destroy them.

It’s show them you *could have* and chose not to.

That lesson stays with a man forever. And it makes sure he never forgets why some lines don’t get crossed.

The story of the photo album became legend in New York’s underworld. Told and retold in different versions, with different details, but always ending the same way.

Bumpy Johnson protected his wife’s honor without spilling a single drop of blood. No shootouts. No bodies. No war.

Just a leather‑bound photo album and a message so clear that even the five families had to acknowledge it:

In Harlem, you don’t touch what belongs to Bumpy Johnson.

And if you’re foolish enough to try, you don’t get a second chance. You get one warning.

And if you’re smart, you take it.

News

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid….

“Is This Pig Food?” – German Women POWs Shocked by American Corn… Until One Bite

April 1945, a muddy prison camp near Koblenz, Germany. Thirty‑four German women sat on wooden benches. Their uniforms were torn,…

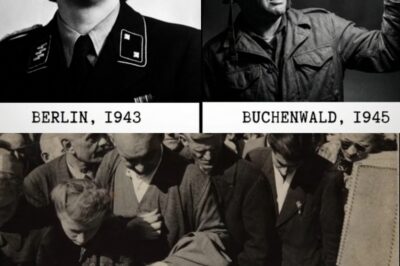

What American Soldiers Found in the Bedroom of the “Witch of Buchenwald”

April 13th, 1945. The outskirts of Weimar, Germany. A beautiful, sunny spring day. A group of American soldiers from the…

End of content

No more pages to load