October 1966. A stuntman dies on John Wayne’s set. The studio’s offer to his widow is an insult. Wayne hears about it—and what he does next makes the studio regret that offer. Here’s the story.

The horse falls wrong. Pete Keller hits the ground at a fatal angle. His neck snaps—a sound that carries across the desert. Everyone hears it: cast, crew, director, John Wayne. They all know Pete Keller is dead.

It’s October 15, 1966, Monument Valley, Arizona. They’re filming The War Wagon, a big-budget Universal Pictures western. Wayne is the star. Pete is the stunt coordinator—was the stunt coordinator. Now he lies in the dirt while fifty people stand stunned.

Medics arrive—no pulse, no breath. Pete Keller is 38, married, with three kids ages 6, 8, and 11. Fifteen years doing stunts, never a serious injury until today. Wayne stands twenty feet away, face like stone, hands shaking.

Production shuts down. The sheriff arrives, takes statements, rules accidental death. The body is taken away. The crew returns to the motel in silence. What is there to say? A man died doing the job meant to be Wayne’s, but couldn’t be—he’s sixty and a cancer survivor.

Someone died being John Wayne. That’s what stuntmen do—they risk and sometimes die being other people. Before we continue: ever seen something at work no one wanted to talk about? Drop your state in the comments. Mid-October desert—hot days, fast-falling cold nights. The crew is staying in Mexican Hat, Utah, forty miles from set.

The War Wagon is a major production—Kirk Douglas, Howard Keel, Robert Walker Jr.—good cast, good script, big money. Universal is spending $3 million—serious for 1966. Stunt work is dangerous; everyone knows. It pays well: Pete makes $15,000 a year, double most men’s wages.

It’s enough for a house, to support a family, to dream of college for the kids. You earn every dollar by risking your life. Pete’s wife, Linda, is 34—his high school sweetheart. Married at 19, followed him to Hollywood, patched him up, sent him back out. That’s what stunt wives do—wait, worry, pray.

On October 15, something goes wrong. That same day, the studio sends someone to Linda’s house—a junior executive type, suit and tie, clipboard. He sits at her kitchen table. The kids are in the other room with a neighbor. Linda’s eyes are red; she hasn’t slept or eaten. Six hours ago, the call came: her husband is dead.

The lawyer is polite and practiced. He slides out papers. “Mrs. Keller, Universal Pictures offers our deepest condolences. Pete was a valued member of our team.” Linda stares, silent. “We’d like to offer a settlement—$5,000. Sign here; you’ll have a check within two weeks.”

Linda looks at the number. Five thousand dollars—for her husband’s life, for fifteen years of risking everything, for leaving her with three kids and a mortgage. “It’s a generous offer, Mrs. Keller. Pete knew the risks. This isn’t a liability situation. The studio offers this out of goodwill.”

Her hands shake. “Goodwill?” “Take it or leave it. This offer expires in 48 hours.” He slides the papers across the table and leaves her with a number that values her husband at less than a new car. John Wayne doesn’t sleep that night in his Mexican Hat motel room. He can’t stop thinking about Pete, Linda, and those kids—about the sound.

Forty years in the business—Wayne has seen injuries, not death. Not on his set. Not for a stunt meant to be his. He keeps thinking: Pete died being me. Pete died so I could pretend to be a cowboy. Pete died so Universal could make $3 million. At 6 a.m., his phone rings—the unit production manager.

He explains the studio’s settlement: $5,000. Wayne is silent for a long time. “Standard offer, Duke. Accidental death, no liability.” “Pete left a wife and three kids.” “We know. That’s why we’re offering anything.” Wayne hangs up, sits on the bed, thinks of his seven children—different marriages, all his. What if someone told them their father was worth $5,000?

Wayne calls his business manager. “How much cash can I access today?” Forty-eight hours later, Linda sits at her table. The papers are still there—unsigned. The lawyer called twice; the deadline is today. Five thousand or nothing. She needs the money—mortgage, food, kids—but signing feels like saying Pete was worth $5,000.

There’s a knock. Linda opens the door. John Wayne stands there. She recognizes him instantly but doesn’t understand why he’s here. “Mrs. Keller?” “Yes.” “I’m John Wayne. I need to talk to you about Pete.” She lets him in. He sits at the same table as the lawyer two days earlier—but he doesn’t pull out papers.

“I’m sorry about Pete. He was a good man.” Linda nods, unable to speak. “I heard about the studio’s offer—$5,000. That’s an insult.” Tears fill her eyes. “I don’t know what to do. I need the money. But signing feels like saying Pete didn’t matter.” Wayne reaches into his jacket, places an envelope on the table. “This is $50,000. From me—personally—for you and your kids.”

Linda stares, struggling to process. “I can’t accept this.” “Yes, you can. Pete died making my movie. He died because I’m too old to do my own stunts. That makes it my responsibility.” “Mr. Wayne, you don’t owe me anything.” “Yes, I do. Pete died being me. The least I can do is take care of his family.”

Wayne isn’t finished. He pulls out a business card, writes a number. “This is the studio head’s direct line. I’m calling him today. Universal will set up a monthly stipend—$500 for life—and college funds for all three kids. Full tuition, wherever they choose.” Linda sobs. “Why would they do that?”

Wayne’s jaw tightens. “Because I’ll tell them if they don’t, I’m walking off every picture I owe them—and I’ll make sure every newspaper in America knows why.” That afternoon, Wayne calls the studio head. Thirty minutes. He doesn’t yell or posture—he states facts. Pete died making a Universal picture. A widow and three kids remain. Five thousand dollars is not acceptable.

The executive cites liability, insurance, standard practice. Wayne cuts him off. “I don’t care about standard practice. I care about right and wrong. Pete died working for you. His family deserves better than $5,000 and a handshake.” “What do you want, Duke?” “$500 a month for Linda for life and college funds for all three kids—full tuition.”

“That’s going to cost us.” “I know what it costs. Do it—or I walk off every picture. Green Berets. True Grit. Everything I owe. I’m done.” Silence. The studio head calculates. John Wayne is Universal’s biggest star. Losing him would cost far more than a lifetime stipend. “Fine. We’ll do it.” “In writing—contract, legal—so no one can undo it after I’m gone.” “You’ll have it by Monday.”

Wayne hangs up and exhales. It’s not enough—nothing brings Pete back—but at least the kids can go to college, Linda can keep the house, and the studio can’t pretend Pete didn’t matter. Six weeks later, Linda receives her first stipend check—$500, like clockwork. Her mortgage is $700; the stipend covers most. Wayne’s $50,000 covers the rest—food, clothes, and time to figure out life without Pete.

Linda never remarries. Pete was her person. She raises the kids, works part-time, and never takes the stipend for granted. Every check reminds her someone fought for her when the system wanted to forget. All three children go to college—teacher, engineer, doctor—on Universal’s dime, because John Wayne made them pay it.

Linda receives that stipend for 37 years, until her death in 2003 at age 71. Thirty-seven years of $500 a month—$222,000—plus Wayne’s $50,000 and three college educations. That’s what Pete Keller’s life was really worth—not $5,000 with an insult and a deadline, but a lifetime of dignity for his family.

In 2005, Linda’s daughter, Sarah Keller—now 43, a high school history teacher in San Diego—writes to the John Wayne Estate. She recounts her father’s death, the $5,000 “offer,” and the day John Wayne sat at their kitchen table. “My mother received that stipend until the day she died—every month for 37 years. We went to college because of it. We kept our home because of it. My mother kept her dignity because someone fought for her when she had no fight left.”

“Duke didn’t know us. We were strangers. But he saw my mother’s pain and decided it mattered. He used his power to force a studio to do the right thing—not because he had to, but because he chose to. My father died making movies, but John Wayne made sure we didn’t die with him.” She tells her students that’s how you measure a man—not by what he has, but by what he gives to those who can’t give back.

Her letter sits in the John Wayne Museum beside a photo of Pete Keller, the settlement papers Universal wanted Linda to sign, and Wayne’s personal $50,000 check. If this story moved you, hit subscribe and drop a like. Tell us what you think of what John Wayne did for Linda and her family. And unfortunately, they don’t make men like John Wayne anymore.

News

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

– Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying German prisoners slowed at Camp Ruston as nineteen women pressed their faces against…

Japanese Kamikaze Pilots Were Shocked by America’s Proximity Fuzes

-April 6, 1945. Off Okinawa in the East China Sea, dawn breaks over Task Force 58 of the U.S. Fifth…

When This B-26 Flew Over Japan’s Carrier Deck — Japanese Couldn’t Fire a Single Shot

At 7:10 a.m. on June 4, 1942, First Lieutenant James Muri dropped to 200 feet above the Pacific, watching thirty…

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home

November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

Why British Carriers Terrified Japanese Pilots More Than the Mighty U.S. Fleet

April 6, 1945. A Japanese Zero screams through the morning sky at 400 mph. The pilot, Lieutenant Kenji Yamamoto, has…

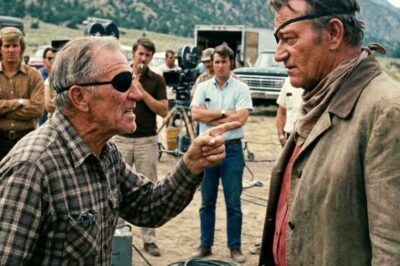

The Day John Wayne Met the Real Rooster Cogburn

March 1969. A one-eyed veteran storms onto John Wayne’s film set—furious, convinced Hollywood is mocking men like him. What happens…

End of content

No more pages to load