July 11th, 1968.

The day the earth shook in Harlem.

To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a year of fire and blood. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in Memphis. Robert Kennedy was dead in Los Angeles. Cities were burning, and the Vietnam War was tearing the country apart.

But in Harlem, on this humid, gray Thursday morning, the world had stopped for a different reason. The king was dead. Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, the man who had ruled the Uptown underworld for 40 years, the man who had outlived the mafia, the police, and Alcatraz, lay in a bronze casket at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church.

He had died the way he lived—surrounded by his people—eating fried chicken at Wells Restaurant, clutching his chest as his heart finally gave out. The funeral of Bumpy Johnson was not just a burial. It was a coronation of memory.

The streets of Harlem were gridlocked. Thousands of people lined Lenox Avenue, climbing onto fire escapes, hanging out of windows, standing on car roofs just to get a glimpse of the hearse. It was a sea of Black faces, a mixture of grief and anxiety.

They weren’t just mourning a man. They were mourning an era. Bumpy had been the dam holding back the flood. With him gone, everyone knew the chaos that was coming.

The heroin dealers, the young Turks, the Italian families—they were all circling like vultures, waiting for the dirt to hit the lid of the coffin. Inside the church, the air was thick enough to choke on. It smelled of expensive lilies, old wood, and fear.

The pews were packed with the who’s who of the Black experience. There were jazz musicians, judges, politicians, and pimps, all sitting shoulder to shoulder. Flashbulbs popped intermittently, illuminating the somber faces of men who had killed for Bumpy and women who had loved him.

And sitting in the front row, a figure carved out of obsidian and grief, was Mayme Hatcher Johnson. Mayme looked regal. She wore a black veil that obscured her eyes but could not hide the set of her jaw.

She sat with her back straight, her gloved hands folded in her lap. To the public, she was the grieving widow, the stoic matriarch saying goodbye to her husband. But inside, Mayme was fighting a different war.

She was scanning the room. She knew everyone here. She knew who was loyal, and she knew who was checking their watch, waiting to carve up Bumpy’s territory.

She saw the FBI agents in the back row, taking notes. She saw the young hustlers eyeing the jewelry on the older bosses. But there was one person Mayme was looking for—one person she had prayed would have the decency, the common sense, to stay away.

Bumpy Johnson was a man of many appetites. He loved poetry. He loved chess. And he loved women. Mayme knew this. She had made her peace with it decades ago.

She understood that being married to a king meant sharing him with the world, and sometimes sharing him with other women. She had tolerated the flings, the late nights, the business meetings that lasted until dawn.

She tolerated them because she knew that, at the end of the day, Bumpy always came home. She was the wife. She was the partner. The others were just hobbies.

However, in the last year of his life, there had been a new hobby. Her name was Dolores. She wasn’t like the others. She wasn’t a sophisticated writer like Helen Lawrenson, and she wasn’t a quiet girl from the neighborhood.

Dolores was young, loud, and dangerously ambitious. She was part of the new generation—the generation that didn’t care about the code. She didn’t care about discretion.

She liked the flash. She liked being seen on the arm of the Godfather, driving his cars, spending his money. She had been a thorn in Mayme’s side for months, parading around Harlem as if she had a ring on her finger.

Bumpy, in his old age, had been soft on her. He enjoyed the adoration. He let her get away with things he never would have tolerated in his prime. Mayme had warned Bumpy.

“She doesn’t respect the game, Ellsworth,” Mayme had told him. “She thinks this is a movie. She’s going to embarrass you.” Bumpy had just laughed, brushing it off. “She’s just a kid, Mayme. Let her have her fun.”

Now Bumpy was dead. The fun was over. And Mayme prayed that Dolores would have the respect to stay in the shadows where she belonged.

A funeral is a sanctuary. It is the final moment of dignity a family has. It is not a place for mistresses. It is not a place for side pieces.

It is a place for the wife.

The organ music swelled, filling the cavernous church with a mournful hymn. The service began. The preacher, a man with a booming voice who had known Bumpy since they were boys, began to speak about Bumpy’s charity, his heart, his role as a protector.

“He was a lion,” the preacher shouted. “A lion who watched over this jungle.” The congregation murmured, “Amen.”

Mayme nodded, tears finally tracking down her cheeks beneath the veil. For a moment, she allowed herself to just be a widow. She allowed herself to feel the crushing weight of the loss.

Then the doors at the back of the church creaked open. It wasn’t a subtle entrance. A shaft of bright July sunlight cut through the dim sanctuary, blinding the people in the back pews.

Heads turned. The murmuring stopped. The preacher faltered for a fraction of a second. Walking down the center aisle, heels clicking on the stone floor, was Dolores.

The audacity was breathtaking. In a sea of somber black and navy suits, Dolores was wearing a dress that screamed for attention. It was black, yes, but it was tight—too tight.

It was cut low, revealing cleavage that had no place in the house of the Lord. She wore a wide-brimmed hat that rivaled Mayme’s and huge dark sunglasses. She wasn’t walking with her head down in respect.

She was walking like she was on a runway. She was walking like she was the star of the show. A ripple of shock went through the church.

The old-timers, the men who had served with Bumpy since the 1930s, looked at each other in disbelief. This was a violation of the highest order.

You do not disrespect the family at the funeral. You do not show up to the burial of the king dressed like a showgirl.

Mayme felt the shift in the room before she saw it. She heard the gasps. She felt the tension spike. She slowly turned her head.

Through the black lace of her veil, she saw Dolores strutting down the aisle. Mayme didn’t move. She didn’t gasp. She went perfectly still.

Her hands, which had been clutching a handkerchief, unclenched and then smoothed the fabric of her dress. It was a terrifying calmness. Inside, a fire was igniting in Mayme’s chest that burned hotter than grief.

This wasn’t just disrespect. It was a challenge. Dolores was telling the world, “I mattered, too. I was important. I have a claim here.”

Dolores didn’t stop at the back. She didn’t slip into an empty seat near the door. She kept walking. She walked past the associates. She walked past the cousins.

She walked all the way to the third row—just two rows behind Mayme—and squeezed herself into a seat that wasn’t there, forcing a respectable elderly aunt to shift over. The church was silent.

The preacher cleared his throat, trying to regain control of the room, but the damage was done. All eyes were on the third row.

Dolores took off her sunglasses with a theatrical flourish and began to dab at dry eyes with a tissue, making loud, performative sobbing noises. “Oh, Bumpy!” she wailed, just loud enough to be heard over the sermon. “My sweet Bumpy!”

Mayme sat like a statue. She didn’t turn around. She stared straight ahead at the bronze casket. But the people sitting closest to her—Bumpy’s closest lieutenants, Junie and Red—saw the change in her eyes.

They saw the steel shutter come down. They knew that look. It was the same look Bumpy used to get right before he ordered a hit.

The service dragged on for another hour. It was an hour of torture for the congregation. Every time the preacher made a poignant point, Dolores would let out a dramatic moan or a “Yes, Lord,” that drew attention back to her.

She was hijacking the funeral. She was turning a tragedy into a soap opera. The disrespect was accumulating layer by layer, building a pressure cooker inside St. Martin’s.

Finally, the service concluded. The choir began to sing “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” The pallbearers—six massive men, the toughest enforcers in Harlem—stepped forward to lift the heavy bronze casket.

The congregation stood. Mayme rose slowly, supported by her family. She turned to follow the casket out of the church.

As she turned, her eyes locked with Dolores in the third row. Dolores didn’t look away. She stared right back at Mayme.

And then she did something unforgivable. She smirked.

It was a tiny, fleeting expression, gone in a second, replaced by a mask of faux grief. But Mayme saw it. It was a look of triumph.

A look that said, “I’m here, and there’s nothing you can do about it. I’m part of the legend now.” Mayme walked past her. She didn’t say a word.

She kept her head high, walking behind the body of her husband, leading the procession out into the blinding afternoon sun. The crowd outside roared as the doors opened.

The humidity hit them like a physical wall. The hearse was waiting at the bottom of the stone steps, its engine idling.

Mayme descended the steps, her heart pounding a slow, heavy rhythm. Just get him in the car, she told herself. Just get to the cemetery. Don’t make a scene.

Not today. Not for Ellsworth.

She reached the sidewalk. The pallbearers began to slide the casket into the back of the hearse. Mayme stood by the open door of the family limousine, the lead car in the procession.

She was ready to get in, to close the door on this nightmare, and mourn in peace. But Dolores wasn’t done.

The younger woman had pushed her way through the crowd exiting the church. She had maneuvered past the family members, past the guards.

She burst out onto the sidewalk, her heels clicking on the pavement. She wasn’t heading for her own car. She wasn’t heading for the crowd. She was heading for the hearse.

Dolores rushed toward the open back of the hearse, where the casket was still visible. She threw her arms out, creating a spectacle for the thousands of people watching from the street.

“Don’t take him!” she screamed, creating a scene fit for a movie. “I need to say goodbye! He loved me! He loved me best!”

The crowd went silent. The paparazzi raised their cameras. This was the shot, the scandal, the mistress throwing herself on the casket while the widow watched.

Mayme froze. Her hand was on the door of the limousine. She watched as this woman—this child—desecrated the final journey of the greatest man Harlem had ever known.

She watched Dolores reach out to touch the bronze handle of the casket, wailing about her baby. Something snapped in Mayme Johnson.

The code of silence, of dignity, of looking the other way—it evaporated. Bumpy was gone. The rules had changed.

There was no one left to protect this girl. And there was no one left to hold Mayme back.

Mayme let go of the limousine door. She turned. She didn’t run—queens don’t run—but she moved with a terrifying speed.

She walked straight toward the hearse, her heels striking the pavement with the force of a gavel coming down for a death sentence. Dolores was so busy performing for the crowd, so busy making sure the cameras saw her tears, that she didn’t see the storm coming until it was right on top of her.

Mayme didn’t scream. She didn’t shout insults. She simply reached out. And that is when the legend of Mayme Johnson was truly written—not as the wife who stood behind the man, but as the woman who stood over him.

She reached out with a gloved hand and grabbed. The silence on Lenox Avenue was absolute. Thousands of people held their breath.

The traffic had stopped. The wind had died. All eyes were focused on the two women standing at the back of the hearse—the grieving widow in the veil and the screaming mistress in the tight dress.

Dolores had her hand on the casket handle, posing, wailing, soaking in the attention. She thought she had won.

She thought she had successfully inserted herself into history. She thought Mayme Johnson was just a passive observer, a relic of the past who would quietly get in her car and fade away.

She was wrong.

Mayme Johnson didn’t grab Dolores by the arm. She didn’t grab her by the shoulder to gently guide her away. Mayme reached out with the strength that comes from 40 years of surviving gang wars, police raids, and heartbreak.

She grabbed Dolores by the hair.

It wasn’t a little tug. It was a vice grip. Mayme’s gloved fingers tangled into the expensive, high‑piled wig that Dolores was wearing.

In one fluid, violent motion, Mayme yanked. “Get your hands off him,” Mayme hissed. The voice was low, guttural, and terrifying.

Dolores’s head snapped back. Her scream changed from theatrical grief to genuine pain. “Ow! Let go! You’re crazy!” she shrieked, flailing her arms, trying to claw at Mayme’s hand.

But Mayme didn’t let go. She twisted her grip, forcing Dolores to stumble backward, away from the casket. The crowd gasped.

A collective “Ooh!” rippled through the onlookers. This wasn’t a polite society snub. This was a street fight. This was Harlem justice.

“You think this is a show?” Mayme said, her voice rising now, carrying over the crowd. “You think this is a stage for you to audition on? This is my husband. This is my life.”

Dolores tried to spin around, tried to regain her balance and her dignity. “He loved me,” she spat back, her eyes wild behind the crooked sunglasses. “He told me I was the one. You were just the habit, old woman.”

It was the wrong thing to say. Mayme didn’t just hold on to the hair. She used it as a lever. She dragged Dolores away from the hearse, away from the sanctuary of the dead.

Dolores’s heels skidded on the pavement. Her hat fell off and tumbled into the gutter. The illusion of glamour was shattered instantly.

Now she was just a messy, screaming girl being handled by a matriarch. “He didn’t love you,” Mayme said, pulling Dolores close, face to face.

Mayme lifted her veil, revealing eyes that were dry and burning with cold fire. “He tolerated you. He bought you things to keep you quiet. But look where you are now. You’re outside. You’re always going to be outside.”

Mayme gave one final, decisive yank. The wig—the symbol of Dolores’s vanity, her falseness—came loose. It shifted violently, sliding off Dolores’s head, leaving her natural hair exposed and disheveled underneath.

Mayme shoved her. Dolores stumbled back, tripped over her own feet, and fell hard onto the sidewalk. She landed on her hands and knees, the expensive black dress tearing at the knee.

The wig dangled from Mayme’s hand for a split second before she dropped it onto the ground next to Dolores like a piece of trash. The paparazzi cameras flashed like lightning.

Pop. Pop. Pop.

They captured the image that would become legendary in the neighborhood: the mistress on her knees in the dirt and the queen standing over her, adjusting her gloves.

“You don’t ride with the family,” Mayme said, her voice cutting through the humid air. “And you don’t touch the king. Go home, little girl, before I bury you next to him.”

Dolores looked up. She looked at the crowd. She looked for sympathy. She found none.

The people of Harlem knew the code. They knew respect. And they saw exactly what had just happened. They saw a woman trying to steal valor and getting checked by the real power.

Laughter started to bubble up from the onlookers—mocking laughter. “Tell her, Mayme!” someone shouted from a fire escape. “Respect the queen!” another voice yelled.

Dolores scrambled to her feet. Her face was bright red. She grabbed her wig from the ground, clutching it to her chest like a dead animal.

She looked at the hearse, then at Mayme. The arrogance was gone. The showgirl persona had evaporated. She was humiliated.

She turned and ran, pushing through the crowd, shielding her face from the cameras, disappearing into the sea of bodies on Lenox Avenue.

Mayme watched her go. She didn’t chase her. She didn’t shout any more insults. She simply took a deep breath, smoothed the front of her dress, and adjusted her veil back over her face.

She turned back to the pallbearers, who were standing frozen, unsure of what to do. “Put him in the car,” Mayme said calmly. “We have a schedule to keep.”

The men scrambled to obey. The casket was loaded. The doors were closed. Mayme walked back to the limousine.

Her family was inside, staring at her with wide eyes. Her daughter looked at her, stunned. “Mama,” she whispered as Mayme slid into the leather seat. “I can’t believe you did that.”

Mayme pulled the door shut, sealing them in the cool, quiet air of the car. She looked out the tinted window at the crowd, which was now cheering, clapping, celebrating the show of strength.

“Bumpy worked too hard for his name,” Mayme said softly, removing her gloves and placing them in her purse. “I wasn’t going to let a fifty‑dollar girl tarnish a million‑dollar legacy.”

The procession began to move. The long line of black Cadillacs wound its way through Harlem—past the jazz clubs Bumpy owned, past the corners where he sold his numbers, past the people he had fed.

The incident at the church spread through the neighborhood faster than the cars could drive. By the time they reached Woodlawn Cemetery, the story was already being embellished.

“Mayme punched her.”

“Mayme cut her.”

“Mayme threw her into traffic.”

But the truth was simpler and more powerful. Mayme had asserted her position.

For 40 years, people had wondered if Mayme Johnson was just a figurehead. They wondered if she was weak for staying with a man who had so many women.

That afternoon, on the sidewalk in front of St. Martin’s, they got their answer. She wasn’t weak. She was patient.

And when her patience ran out, she was dangerous.

The burial was peaceful. There were no more interruptions. Bumpy was lowered into the ground in a section of the cemetery reserved for the elite.

Mayme threw the first shovel of dirt onto the casket. She didn’t cry then. She saved her tears for the privacy of her empty house.

That night, Harlem held a wake that lasted until dawn. They poured liquor on the corners. They played Bumpy’s favorite records.

And in every bar from the Red Rooster to Small’s, the topic of conversation wasn’t just Bumpy. It was Mayme.

“Did you hear what she did?”

“She snatched that girl bald.”

“Bumpy’s gone, but the Johnson name ain’t dead.”

The incident with the mistress served a crucial purpose. With Bumpy gone, the wolves were ready to tear his empire apart.

The Italian mob, the young drug dealers, the corrupt cops—they were all planning to swoop in and take what Bumpy had built. They assumed Mayme was a soft target.

They assumed she would retreat into widowhood and let them loot the accounts. But the story of the wig-snatching sent a signal. It told the streets that Mayme Johnson was not to be trifled with.

It told them that she still had fight in her. And it bought her respect. In the months that followed, when men came to her to discuss business or try to intimidate her into signing over deeds to properties, they remembered the look in her eyes on the church steps.

They remembered that she was the woman who had stood over a screaming mistress and banished her into oblivion. Dolores was never seen in Harlem again.

Rumor had it she moved to Chicago, or maybe down South. She became a ghost story, a cautionary tale told to young girls who thought they could play with fire.

Don’t be a Dolores. Don’t try to wear the crown if you can’t carry the weight.

Mayme lived for many more years. She eventually moved away from the life, but she never lost her dignity. She wrote a book. She told her story.

But she rarely spoke about the funeral incident in interviews. To her, it wasn’t a moment of pride. It was a moment of necessity. It was simply taking out the trash.

Bumpy Johnson was a legend. He was the Godfather of Harlem. But on the day he died, the world learned that every godfather needs a godmother.

And if you cross her, you won’t just lose your reputation. You might just lose your hair.

As the sun set on that chaotic July day in 1968, the streets of Harlem quieted down. The king was resting. The queen was home.

And the order of things, fragile as it was, had been maintained.

Mayme sat in Bumpy’s favorite chair, looking at a photo of him from the 1940s—young and sharp and dangerous. “I handled it, Ellsworth,” she whispered to the empty room. “I handled it.”

And somewhere in the great beyond, Bumpy Johnson was probably smiling. Because he knew better than anyone that he had married the toughest gangster in New York.

Thanks for listening, folks. If you liked that story and want more, be sure to like the video and subscribe so you don’t miss any Bumpy Johnson stories.

News

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid….

“Is This Pig Food?” – German Women POWs Shocked by American Corn… Until One Bite

April 1945, a muddy prison camp near Koblenz, Germany. Thirty‑four German women sat on wooden benches. Their uniforms were torn,…

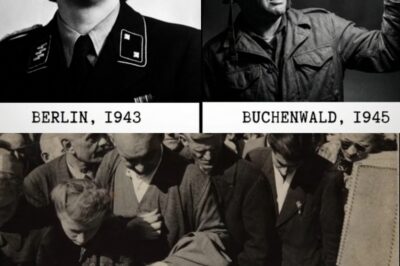

What American Soldiers Found in the Bedroom of the “Witch of Buchenwald”

April 13th, 1945. The outskirts of Weimar, Germany. A beautiful, sunny spring day. A group of American soldiers from the…

German Mechanics Were Shocked When They Saw American Trucks Crossing Mud Without Stopping

August 17th, 1944. The morning mist clings to the abandoned airfield outside Chartres, France. In a makeshift Wehrmacht repair depot,…

End of content

No more pages to load