There were no trenches, no tanks, no clouds of smoke.

There were rows of trees. Peach, grape, plum. Earth baked hard by sun. Irrigation ditches glinting under endless blue sky.

But history doesn’t always break in places that look like war.

Sometimes it breaks between two neighboring fields.

The day the trains came

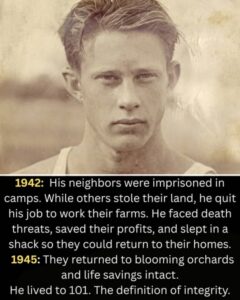

In February 1942, the United States signed fear into law.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced evacuation and incarceration of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Citizens, legal residents, children, grandparents—anyone with Japanese ancestry was suddenly labeled a potential threat.

In small farming towns like Florin, near Sacramento, the news seeped in slowly at first.

Rumors. Notices. Whispers in church pews and at feed stores:

“They’re going to move the Japs.”

“They’re talking about camps.”

“They say it’s for national security.”

Then the rumors grew teeth.

Posters went up on telephone poles.

Orders were nailed to utility posts and tacked onto the walls of grocery stores.

All persons of Japanese ancestry—alien and non‑alien—must report…

In the Tsukamoto house, someone read the notice aloud.

In the Nitta house, it was held in shaking hands.

In the Okamoto house, a child stared at the paper, not fully understanding the words—but knowing from their parents’ faces that life had just split into “before” and “after.”

They had ten days. Sometimes less.

To sell what they could.

To pack what they couldn’t bear to leave.

To decide what to do with the most fragile thing of all: hope.

On the day the trains came, Florin’s streets were lined with suitcases and boxes. Belongings strapped onto car roofs, children clutching dolls, elders leaning on canes.

The orchards stood in neat lines behind them, trees heavy with the promise of fruit.

No one knew if they would ever see those trees again.

Bob Fletcher stood beside the road and watched his neighbors—the Tsukamotos, the Nittas, the Okamotos—climb into buses and trucks, then onto trains bound for assembly centers and, eventually, internment camps in remote deserts and swamps.

Bob knew these families. He knew their land. He’d walked their fields as an agricultural inspector, checking for pests, disease, water issues. They were farmers—some third‑generation Americans whose grandparents had cleared the land and planted the first saplings.

They weren’t enemies.

They were the people who had fixed his irrigation lines and shared their peaches.

They were the ones whose kids waved to him from the edge of the road.

The trains shuddered, lurched forward, and left.

Behind them, the orchards went quiet.

Silence settled between the trees like dust.

On the fences, new signs appeared:

“Evacuation Completed.”

The vultures circle

It did not take long for the opportunists to arrive.

They came in trucks and cars, wearing friendly smiles that didn’t reach their eyes. They talked at church, at the diner, at the feed store. Their words were casual. Their intentions were not.

“Those Japs are gone.”

“Those farms are going to go to waste.”

“Shame to let good land rot.”

“Could pick them up cheap at tax sale.”

Across the valley, Japanese American farms were sold off for pennies on the dollar, or simply taken over by people who considered an empty house an invitation.

In their minds, the families forced onto trains had forfeited their rights the moment the government labeled them “enemy aliens,” even when they were citizens born under the same flag.

Bob heard the conversations.

He saw the way people’s eyes gleamed when they talked about vacant land.

He also saw something else: the fragility of a lifetime’s work.

Orchards are not like buildings. You can’t simply lock the door and come back in three years expecting everything to be fine.

Trees need tending.

They must be pruned, watered, protected from pests.

If you ignore them for a season, they suffer.

Ignore them for three, and they die.

For the Tsukamotos, the Nittas, the Okamotos, those trees were not just property. They were memory. They were inheritance. They were proof that generations of back‑breaking labor had meant something.

Watching the orchards go to seed would have been a kind of killing too.

Bob Fletcher could have turned away.

He had a stable job as a state agricultural inspector. He had security. He had no legal obligation to do anything.

What he had was something else: a conscience.

“I will keep your trees alive.”

Bob did something most people do only in stories.

He walked away from safety.

He quit his job as an agricultural inspector. The paycheck, the title, the stability—gone.

Then he went to the families: the Tsukamotos, the Nittas, the Okamotos. He sat with them in the tense days before they were forced to leave and made a promise that sounded unrealistic, even reckless:

“I will keep your trees alive,” he told them.

“I will pay your taxes.

I will keep your land.

Until you come home.”

The words “if you come home” hung in the air unspoken—because everyone in that room understood the truth: there were no guarantees.

The families offered him legal arrangements, agreements that would allow him to run the farms. But they also offered something else, something intimate:

“Please,” they said. “Live in our house. Use our beds. You’ll need the comfort.”

They were worried about him.

This man who was taking on impossible labor in the midst of war.

Bob looked at their houses—comfortable, well‑furnished, with soft beds and real roofs—and shook his head.

He thought about the barracks and cots waiting for them behind barbed wire.

He thought about the guards. The dust. The cold.

He couldn’t do it.

“I can’t sleep in your beds,” he said gently, “while you sleep on cots in a prison camp.”

Instead, he moved into a migrant worker’s bunkhouse on the edge of the property—a rough wooden shack that had never been meant for comfort.

Winter turned it into a box of cold air. Summer turned it into an oven.

Even after he married his wife, Teresa, they stayed in that shack together. They could have moved into one of the larger houses. They deliberately did not.

Bob didn’t just want to keep the land alive. He wanted to keep faith.

Eighteen‑hour days in someone else’s orchard

From the moment the families left, Bob’s life became a cycle of exhaustion.

He took on the work of three families.

Three orchards.

Three tax bills.

Three sets of expectations resting on his shoulders.

The days started before dawn. He’d pull on his boots in the dim light of the bunkhouse, drink coffee that never seemed strong enough, step into air still cold from the night.

He pruned trees—climbing ladders, cutting back branches, knowing exactly which limb to remove and which to spare. Pruning is an act of both destruction and faith: you cut now so there will be fruit later.

He patched irrigation lines, dug ditches, moved water. In the summer, the California sun was unforgiving. It baked the ground, burned the back of his neck, coated his skin with dust and sweat.

He dealt with insects, disease, bad weather. Every farmer’s enemy showed up, as it always does, on its own schedule.

During harvests, the work intensified. Fruits don’t wait. When they’re ready, they’re ready—and if you don’t move fast enough, they rot where they hang.

Bob drove tractors. He loaded crates. He negotiated with buyers. He did bookkeeping late at night, eyes gritty, hands aching, trying to make sense of numbers through fatigue.

Eighteen‑hour days were normal.

Sleep was a luxury.

Rest was rare.

He wasn’t just fighting against nature. He was fighting against something more corrosive.

The community.

The cost of standing alone

War has a way of sorting people—not into “good” and “bad,” but into those who will go along with injustice and those who won’t.

In Florin, many chose to go along.

Some supported the internment openly. Others shook their heads and called it “unfortunate but necessary.” Still others didn’t want to think about it at all.

Bob’s refusal to join the chorus made him a target.

They called him a traitor.

They spat the word “Jap‑lover” at him like poison.

They confronted him on roads and at stores.

“Why are you helping them?”

“They’re the enemy.”

“Think they’d do the same for you?”

“Let their land rot. They’re gone.”

Hatred didn’t stop at words.

They slashed his tires.

They fired a bullet through his barn.

They tracked mud into places they weren’t welcome.

They tried to break more than his resolve—they wanted to break his sense of safety.

Bob heard the threats. He saw the damage. He knew the risk.

He kept working.

He drove to town to buy supplies. He fixed the barn. He replaced the tires. He went back to the fields.

Fear was real, but so was something else: his decision.

He had already chosen.

No amount of intimidation was going to turn him into the kind of person who would walk away now.

The temptation to take—and the choice to return

The war dragged on.

Months turned into years.

The camps remained full. Families tried to make lives in barracks under watchtowers. Children pledged allegiance to the same flag that had allowed their imprisonment.

Back in Florin, Bob’s position was, on paper, powerful.

The families were gone.

Oversight was minimal.

War chaos meant no one was checking closely.

Many farm managers in those days took advantage of such situations. They pocketed profits. They ignored maintenance. They let orchards die and walked away with whatever cash they could grab.

Bob could have done the same.

No one would have stopped him.

He could have told himself he deserved the money. After all, he was doing all the work, facing all the hatred, taking all the risk.

It would have been easy to justify.

He did the opposite.

He took only enough to live on.

Enough to keep himself and Teresa fed, clothed, and able to keep working.

Every other dollar of profit—every cent—he banked.

He opened accounts in the families’ names. He logged what came in and what went out. He treated their money with more respect than many people treated their lives.

While they lived behind barbed wire, sleeping on cots in barracks and eating institutional food, he was out in their fields, turning sweat into fruit and fruit into income they didn’t even know would be waiting.

Bob wasn’t just tending trees.

He was tending trust.

The war ends. The long train home.

1945.

The war in Europe ended in May. The war in the Pacific ended in August. Images of mushroom clouds and devastated cities filled newspapers. The world staggered into an uneasy peace.

For Japanese Americans, the end of the war did not bring immediate joy. It brought uncertainty.

The government began releasing families from the camps. No fanfare. No apologies. Just instructions:

You are free to go now.

Free to go… where?

Many had lost everything.

While they were imprisoned, strangers had bought their houses for almost nothing or simply taken them over. Businesses were looted, vandalized, or quietly absorbed by others. Bank accounts were frozen or drained. Friends who had promised to “keep an eye on things” had shifted from guardians to owners when no one was watching.

People left the camps with suitcases and little else.

The Tsukamoto, Nitta, and Okamoto families boarded trains back toward California, shadowed by dread.

They had heard stories.

“He went home and found strangers on his land.”

“She went back to her store and it was gutted.”

“They have nothing now.”

As the train drew closer to Florin, their fears grew larger.

What would they find?

Barren fields?

Abandoned houses?

Empty bank accounts?

They had learned, in the harshest way possible, to expect the worst.

The orchards in bloom

The train pulled into the station. The families stepped onto the platform, hearts pounding, stomachs tight.

The California sun felt the same as when they had left. The air smelled like dust and fruit and possibility.

They drove or walked toward their land, bracing for disaster.

Instead, they saw something else.

The orchards were alive.

Trees stood in neat rows, pruned and healthy. Leaves green, branches strong, fruit beginning to ripen. Not wild, not overgrown, not dying.

Crops had been harvested, fields maintained. There were no broken windows. No graffiti. No smashed doors. The houses—those they had been forced to lock and walk away from—stood clean and intact, just as they had left them.

Someone had patched roofs. Someone had fixed fences. Someone had swept floors and kept out the dust.

Someone had cared.

They found Bob Fletcher there, as he had promised he would be—still in work clothes, still carrying the weight of three years on his shoulders.

And then came the part that, for many of them, went beyond anything they had dared to imagine.

He handed them their farms.

And then he handed them their money.

In the bank, in accounts under their names, were three years of profits. Not just scraps. Not just whatever remained after someone took their cut and their neighbor took some more.

Real money.

Real records.

Proof of honesty on top of sacrifice.

For families who had lost so much, it felt like a miracle.

Al Tsukamoto later said:

“Bob Fletcher was the greatest man I ever knew. He saved everything we had.”

In a time when most Japanese Americans came back to find ruins, theft, or erasure, the Tsukamotos, Nittas, and Okamotos found continuity.

Because one neighbor had refused to let fear, hatred, or greed decide what kind of person he would be.

“It was the right thing to do.”

Bob did not seek attention.

He didn’t call newspapers to tell them what he had done. He didn’t write speeches or campaign for recognition.

He went back to his life.

He continued to farm. He grew older. The seasons turned, harvest after harvest passing under his hands. The children he had helped came back as adults, then brought their own kids to meet the man who had saved their families’ futures.

Occasionally, reporters or historians tracked him down, asking:

“Why did you do it?”

“Weren’t you scared?”

“Did you regret it?”

He didn’t give long lectures about morality or citizenship. He didn’t wrap his acts in ideology.

He gave a five‑word answer that was both ordinary and extraordinary:

“It was the right thing to do.”

In those words was a worldview.

Not “It was heroic.”

Not “Someone had to.”

Not “I wanted to show them.”

Just: It was right.

As if the more shocking thing wasn’t that he had done it—but that others hadn’t.

A long life, and a long view of justice

Bob Fletcher lived to be 101 years old.

That meant he had time.

Time to see:

– The children of the Tsukamoto, Nitta, and Okamoto families grow up on land he had kept in trust.

– Their grandchildren running between the same trees, playing in orchards that were not lost to history.

– The United States government, decades later, formally apologize for the internment of Japanese Americans.

– A government check—symbolic, partial, never enough—call what happened to his neighbors “a grave injustice.”

He saw the country that had once imprisoned its own citizens under the banner of “security” begin to, slowly, name what it had done.

But Bob had never waited for the government to decide what was right.

He had decided on his own, in 1942, standing on a dusty road as trains carried his neighbors away.

When the law was wrong, he did not mistake legality for morality.

When the community chose hatred, he did not confuse majority opinion with truth.

When the orchards were abandoned, he did not call theft “opportunity.”

He wasn’t a senator.

He wasn’t a judge.

He wasn’t a general.

He was a farmer. An inspector. A neighbor.

And that was enough.

A roadmap for when the world goes mad

Bob Fletcher did not save the world.

He didn’t stop Executive Order 9066.

He didn’t close the camps.

He didn’t change national policy.

But he did something just as important, on a human scale.

He proved that when a society chooses fear over fairness, ordinary people still have a choice.

He slept in a bunkhouse so his neighbors could someday sleep again in their own beds.

He worked eighteen‑hour days so their trees would be alive when they returned.

He faced bullets, slurs, and social exile so their futures wouldn’t be stolen in the dark.

When the trains took his neighbors away, he didn’t look away.

He walked into their empty fields, picked up their tools, and accepted a responsibility no one had forced on him.

He left us with more than a story.

He left us a set of instructions.

When the laws are unjust:

Remember that legality is not the same as morality.

When your neighbors are targeted because of who they are:

Don’t join the crowd. Don’t stay silent. Don’t profit.

When hatred is easy and indifference is comfortable:

Tend the orchard.

Keep the promise.

Do the right thing—especially when everyone around you has found a reason not to.

Because somewhere, years from now, a child might walk through a door or across a field that still exists only because you refused to let it die.

News

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but…

U.S Nurse Treated a Japanese POW Woman in 1944 and Never Saw Her Again. 40 Years Later, 4 Officers

The rain hammered against the tin roof of the naval hospital on Saipan like bullets. July 1944. Eleanor Hartwell wiped…

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory on Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Boot Lace Trick” Took Down 64 Germans in 3 Days

October 1944, deep in the shattered forests of western Germany, the rain never seemed to stop. The mud clung to…

Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open

17th April 1945. A muddy roadside near Heilbronn, Germany. Nineteen‑year‑old Luftwaffe helper Anna Schaefer is captured alone. Her uniform is…

End of content

No more pages to load