The bet was simple: Dean Martin and Bob Hope would play 18 holes. Winner takes $50,000; loser writes a check. It was May 1968 at Lakeside Country Club—beautiful day, high stakes, two legends. What nobody knew was that Dean had no intention of winning. Not because he couldn’t—he was a scratch golfer—but because he had a different plan.

Dean understood something about Bob that most people didn’t. Bob’s identity was wrapped in competition—ratings, laughs, and especially golf. If Dean won, Bob would smile publicly but obsess privately, replaying every shot and losing sleep. Dean liked and respected Bob and didn’t want to bruise his ego over a game. So he decided: lose—but make it look real.

For 18 holes, Dean played just poorly enough to be believable. He missed putts by inches, landed drives in the rough without going out of bounds, and looked like a very good golfer having an off day. Bob didn’t suspect a thing. He thought he was playing the best golf of his life. When Bob won and Dean handed over the $50,000 check, Bob was elated—while Dean was already setting up the next move.

To grasp why golf mattered so much to Bob in 1968, you have to understand who he was. At 65, he had been famous for over 30 years—radio, movies, TV, and USO tours across World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. He was an American icon and a relentless competitor. Golf was his arena—he played with presidents, stars, and moguls, organized charity tournaments, and trained constantly.

But there was one problem: he couldn’t beat Dean Martin. Dean, a natural athlete and former boxer, moved with effortless grace that translated to sports—especially golf. He was a scratch player—par or better on most courses—and had been quietly beating Bob since the late 1940s. Sometimes they played with Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra, sometimes alone. Bob almost never won, and it ate at him.

In early 1968, Bob challenged Dean to change the narrative—$50,000, winner take all. They were at the Friars Club when Bob suggested it. Dean laughed at the stakes. “You scared?” Bob prodded. Dean smiled: “Of losing? No. Of winning? Maybe.” Bob didn’t understand, but pressed, and Dean agreed.

They set a Saturday in May at Lakeside—just the two of them, no press, no gallery. The night before, Dean called his accountant: set up a $50,000 donation to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “Credit it to Bob Hope,” he said. The accountant was baffled but knew better than to question Dean’s instincts. The donation would go through on Sunday—in Bob’s name.

Saturday dawned perfect—clear skies, slight breeze, ideal golf conditions. On hole one, Bob hit a solid drive; Dean hit one 20 yards past him. Bob braced for the usual outcome—then Dean bunkered an easy second shot and three‑putted. Bob two‑putted and won the hole. Dean smiled: “Nice playing, Bob.” Bob thought, “Maybe today’s my day.”

On hole two, Bob won again. By hole five, he was up three strokes, stunned to be beating Dean Martin. Dean calibrated carefully—just below his actual ability, never suspicious, always plausible. At the turn, Bob led by four, practically glowing as he analyzed shots over sandwiches. Dean listened, smiled, and let him have the moment.

The back nine continued the pattern. Bob was solid; Dean was just off. By 16, Bob led by six; by 18, the math was locked—Bob had won. His final putt dropped, and he pumped his fist. Dean walked over, congratulated him, and pulled out his checkbook. He wrote the $50,000 check on the green and handed it over. Bob was ecstatic, already imagining framing it.

Dean went home and confirmed the donation: $50,000 to St. Jude, credited to Bob Hope, Sunday afternoon. Bob, still riding high, took the check to the bank Sunday morning. He asked to deposit it, maybe with a fancy slip to frame. The teller checked the system and frowned: “Mr. Hope, this check has already been cashed.”

Bob froze. “Impossible—Dean gave it to me yesterday.” The teller explained the funds were transferred to St. Jude at 3:47 p.m.—and credited to Bob Hope. Bob walked out in a daze, then sat in his car and started laughing. Dean had orchestrated the perfect win: Bob got the ego boost and the public credit; St. Jude got $50,000; Dean got the satisfaction of the cleverest kindness.

Bob drove straight to Dean’s house. He found him by the pool, drink in hand, reading the newspaper. “You sneaky bastard,” Bob said, sitting down. Dean smiled: “I have no idea what you’re talking about.” Bob laid it out—the donation, the misses by an inch, the short drive by ten yards. Dean shrugged: “Sounds like I had an off day.”

“Why’d you do it?” Bob finally asked. Dean’s smile softened. “Because you’re my friend, and that win mattered to you more than $50,000 matters to me. You got your win; you get credit for a big donation; St. Jude gets money for sick kids. Everybody wins.” Bob’s eyes went wet. Dean continued: “I’ve seen you after a loss. You can’t let it go. I wanted you to have a great day—and for the money to do real good.”

Bob wiped his eyes and laughed. “You’re impossible. And I’m taking the credit—it’s in my name.” Dean grinned: “Good. You should.” They sat another hour—drinking, talking, laughing—two friends who understood each other perfectly. The story became Hollywood legend, but few knew the full details: Dean had lost on purpose, then quietly donated Bob’s “winnings” in Bob’s name.

In later years, Bob retold it often: “Dean Martin is the only man I know who’d let me beat him at golf, let me think I’d won fair and square, and then donate my winnings to charity in my name. That’s not just generosity—that’s psychology.” At Dean’s memorial in 1995, Bob shared the story and cried. “Dean won that golf game. He just let me think I had.”

The lesson isn’t about golf. It’s about knowing your friends well enough to give them what they truly need—even if that means letting them beat you. Dean could have taken the money and another victory, but he saw deeper. Bob needed the win more than Dean needed cash. And sick kids at St. Jude needed the money more than either man needed pride.

So Dean let Bob have his moment—and then made sure the money did the most good. That’s not pity. That’s emotional intelligence—understanding people and what matters. Bob got his victory. St. Jude got $50,000. And Dean Martin got the quiet satisfaction of being the smartest, kindest guy in Hollywood.

News

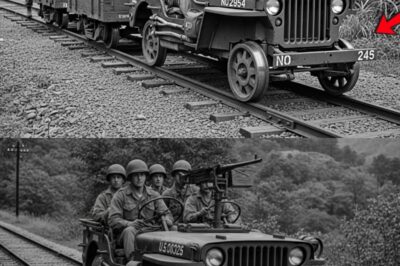

The US Army’s Tanks Were Dying Without Fuel — So a Mechanic Built a Lifeline Truck

In the chaotic symphony of war, there is one sound that terrifies a tanker more than the whistle of an…

The US Army Couldn’t Detect the Mines — So a Mechanic Turned a Jeep into a Mine Finder

It didn’t start with a roar. It wasn’t the grinding screech of Tiger tank treads. And it wasn’t the terrifying…

Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her : “He Took a Bullet for Me!”

August 21st, 1945. A dirt track carved through the dense jungle of Luzon, Philippines. The war is over. The emperor…

The US Army Had No Locomotives in the Pacific in 1944 — So They Built The Railway Jeep

Picture this. It is 1944. You are deep in the steaming, suffocating jungles of Burma. The air is so thick…

Disabled German POWs Couldn’t Believe How Americans Treated Them

Fort Sam Houston, Texas. August 1943. The hospital train arrived at dawn, brakes screaming against steel, steam rising from the…

The Man Who Tried To Save Abraham Lincoln Killed His Own Wife

April 14th, 1865. The story begins with an invitation from President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary to attend a…

End of content

No more pages to load