For forty years, Dean Martin fooled the world. He stumbled on stage, slurred his words, and clutched a glass of whiskey like a lifeline. People called him the king of drunks, the man who couldn’t stand straight without a piano. But one night backstage, seeing tears in his daughter’s eyes, he handed her that glass and whispered two words that shattered the illusion: “Taste it.” What she tasted wasn’t scotch or bourbon—it was the secret to his genius.

To grasp the brilliance of Dean’s creation, you have to understand the character he built. Plenty of performers played drunks—Foster Brooks made a career of it, and Dudley Moore won an Oscar for Arthur. But with them, audiences knew it was acting; when the director yelled “cut,” the performance ended. With Dean, the line vanished. He inhabited the persona so completely that America believed he was perpetually toasted.

Picture it: Thursday night, 10 p.m.—The Dean Martin Show. “Direct from the bar—Dean Martin,” the announcer booms. The doors slide open; he glides down a pole because stairs are too much trouble. Cigarette dangling, tie loosened, crystal glass in hand, he shuffles and sways to the mic with a sleepy smile. He squints at Q cards, mumbles, sips, and the audience roars.

He tries to sing something tender—maybe “Welcome to My World”—then interrupts himself with a giggle or a slur. He leans on a guest, Frank Sinatra or Jimmy Stewart, like he needs help to stay upright. The act was flawless, and the world bought it. The press crowned him king of cool and whispered he was an alcoholic. If you asked in 1968 who drank the most in Hollywood, many would’ve said Dean—not Frank, who actually did.

Here’s the twist: it was a beautiful, meticulously constructed, million-dollar lie. The amber liquid was almost always apple juice—or watered tea. Acrylic ice cubes wouldn’t melt under hot studio lights, preserving the illusion. The cigarette? Often unlit, pure prop. And the slur? Acting—Dean had crisp diction and enough control to sing near-operatic phrasing when he wanted.

Why did he do it? Because Dean understood audiences better than anyone. Perfection intimidates—Frank’s intensity could feel godlike, untouchable. Dean didn’t want to be a god; he wanted to be your friend on the sofa. Playing drunk lowered the stakes: miss a note, forget a line—“Hey, I’m drunk.” It gave him license to be loose, dangerous, and unpredictably charming.

He choreographed chaos with a magician’s precision. He’d “trip” on a mic cord, read the wrong card, or knock over an ashtray with mock confusion. Push too far and it’s tragic; not far enough and it’s flat. For decades, he walked that wire perfectly. But the deception had a cost. While the world laughed, his children lived with the shame others projected onto them.

Deanna adored her father. At home, the real Dean rose early, read the paper, and headed to the golf course. You can’t shoot a 72 with a hangover; you can’t keep scratch without steady hands. He was quiet, watched westerns, ate with the family. Yes, a J&B and soda before dinner—rarely anything more. Private, disciplined, sober when it counted.

School was brutal. Kids parroted their parents: “Your dad was wasted on TV.” “Is he drunk right now?” Deanna watched him at home—calm, steady, making a sandwich—and wondered why the world insisted he was a mess. Then she’d turn on the TV and see him staggering with that glass. The dissonance gnawed at her until she started doubting her own eyes.

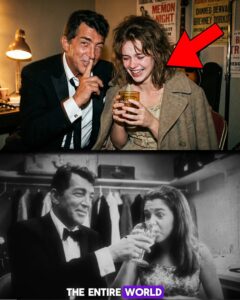

One evening as a teenager, she visited the set. The orchestra tuned, the Golddiggers rehearsed, the audience filed in to see “the drunk.” Backstage in Dean’s dressing room—leather couches, dim lights, the scent of cologne—he sat sharp-eyed as makeup was finished. Deanna, crushed by a day of jabs and whispers, finally cracked. “Why do you do it?” she asked through tears.

He waved the makeup artist away, read the pain on her face, and stood. No lecture about ratings, no sermon on show business. He picked up the famous crystal tumbler—the symbol of his career—and held it out. “Taste it,” he said, gentle but firm. She hesitated, then took a sip—sweet, crisp, cold. “It’s apple juice,” she whispered.

Dean smiled, warm and unguarded. “Apple juice. Sometimes tea. Never booze when I’m working.” She stared at the glass. “But you act so drunk—you stumble, you slur.” He took a sip and shrugged. “That’s the act. I’m an entertainer. John Wayne plays a cowboy. Your Uncle Frank plays the tough guy. If I really drank like that, I couldn’t memorize, hit marks, or take care of our family.”

He nodded toward the stage. “They want Dino the drunk—it makes them laugh, feel good. So I give them the character. In here, I’m Dad. And Dad is sober.” For Deanna, that sip was sunlight cutting through storm clouds. The shame dissolved. Her father wasn’t a mess; he was a master. The stumble was choreography, the slur was diction control, the “forgotten” lyric was planned.

She laughed. “Apple juice? You tricked them all.” Dean winked. “We tricked them all. Our secret, okay? Don’t tell the papers or I’m out of a job.” He kissed her forehead, tugged his tie loose to make it “perfectly messy,” grabbed the glass, and headed out. She watched him inhale, drop his shoulders, glaze his eyes, and tumble into the spotlight. The crowd went wild. Deanna wasn’t embarrassed anymore—she was proud.

Even close friends knew and played along. Frank liked to joke, “I spill more than Dean drinks”—and it was true. That apple-juice confession reveals Dean’s core: consummate professionalism and deep care for his family. He respected the audience and the craft too much to perform impaired; to be truly funny, he had to be in total control. The chaos you saw was discipline you didn’t.

He also protected what mattered. He didn’t care what critics or church groups thought—but he cared what his daughter thought. He couldn’t bear her believing he was weak. When the truth surfaced after his passing, history shifted. Dean went from “lucky drunk” to one of the most underrated comedic actors of the twentieth century, a craftsman of illusion.

We live in a culture obsessed with “authenticity.” Dean came from a different school—the one that says show business is magic. He built a character, Dino the Drunk, who let millions laugh at flaws that felt familiar. He made our vices look charming so we could forgive ourselves. The real Dean? A man drinking apple juice so he could be sharp enough to catch you when you fell.

So next time you see him staggering with that crystal glass, don’t worry about his liver. Smile—you’re watching the greatest con pulled in plain sight. He wasn’t drunk on alcohol. He was drunk on life. If the king of cool fooled you too, tap like and share this reminder that things aren’t always what they seem. And subscribe—next up, the night Dean Martin walked away from the mob and lived to tell the tale. Until then, raise a glass of apple juice and keep swinging.

News

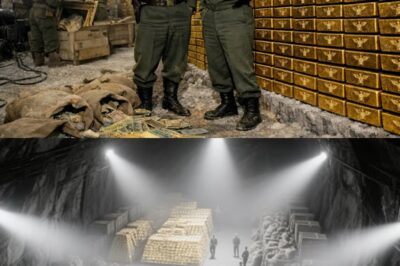

What Patton Found in This German Warehouse Made Him Call Eisenhower Immediately

April 4th, 1945. Merkers, Germany. A column of Third Army vehicles rolled through the shattered streets of another liberated German…

What MacArthur Said When Patton Died…

December 21, 1945. Tokyo, Japan. General Douglas MacArthur sits in his office in the Dai-ichi Seimei Building—the headquarters from which…

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne

If Patton hadn’t moved in time, the 101st Airborne wouldn’t have been captured or forced to surrender. They would have…

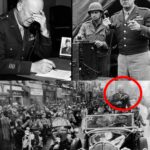

The Phone Call That Made Eisenhower CRY – Patton’s 4 Words That Changed Everything

December 16, 1944. If General George S. Patton hadn’t made one phone call—hadn’t spoken four impossible words—the United States might…

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

End of content

No more pages to load