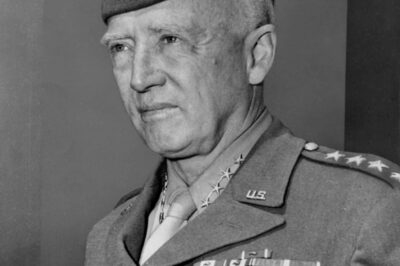

When disturbing allegations about George S. Patton surfaced, his daughter fiercely defended him. Only after her death did her writings reveal the truth. George Smith Patton Jr. was born in 1885 in California to George S. Patton Sr. and Ruth Wilson. The family lived a wealthy life on 128 acres outside Lake Vineyard near Los Angeles.

Patton struggled with learning in childhood, particularly reading and writing. Some historians believe he had dyslexia, which could have hindered his success. He overcame these difficulties through sheer will. In addition to applying to the U.S. Military Academy, he sought universities with cadet programs.

Princeton University accepted him, but he chose the Virginia Military Institute. Both his father and grandfather had attended, and he embraced family tradition. In 1910, at age 24, Patton married Beatrice Banning, daughter of an industrialist. Over the next decade, they had three children.

Being a father did not slow Patton’s ambitions. He rose through the U.S. Army ranks, distinguished by discipline and leadership. Even with a difficult personality, he consistently impressed superiors. His goals were lofty, and his motivation matched them.

A skilled runner and fencer, his athletic success reached new heights in 1912. He competed at the Stockholm Olympics, finishing fifth in the pentathlon—first among non-Swedish competitors. After the games, he studied fencing in France under Adjutant Charles Cléry. Those lessons reshaped his technique and set a new course.

He transferred to the Mounted Service School at Fort Riley, Kansas, as both student and instructor of fencing. He trained superior officers and cavalrymen alike. After two years, he earned the title “Master of the Sword,” the first army officer to receive it. Then, two years later, the world changed—and swords would no longer be enough.

– World War I

The United States entered World War I in April 1917. The age of the sword ended; the age of the tank began. George Patton intended to be ready. In November 1917, he established the AEF Light Tank School near Longré, France.

He studied tanks, secured vehicles, and personally built out training operations. His expertise positioned him to lead the U.S. First Provisional Tank Brigade under Colonel Samuel Rockenbach’s Tank Corps in the First Army. In combat, he issued a firm order: no American tank would surrender. Patton’s doctrine was uncompromising.

In September 1918, he was wounded during an expedition into German territory. His report documented a leg wound with the round exiting a few inches below his back. He recovered quickly and returned to duty. His return was brief; hostilities ended just before he turned 33.

– World War II

Between wars, Patton was assigned to Hawaii in 1934 as a lieutenant colonel. The lack of action made him miserable, and he turned to the bottle. With his family in Hawaii was Jean Gordon, his 21-year-old niece by marriage. During this period, he apparently engaged in a scandalous affair with the young woman.

By 1939, as World War II began, Patton was a colonel. His priority was to bolster U.S. power in armored forces. Promotions followed in rapid succession, and by 1942 he commanded the First Armored Corps. By then, he was the world’s most influential figure in armored combat doctrine.

Patton’s ego was a constant issue. Soon after the U.S. entered the war, he led Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of Vichy French territory in North Africa. He commanded 33,000 men and 100 ships. His strategy overwhelmed opposition and forced an armistice.

After victory, he established a naval port in the area. He was then appointed commanding general of the II Corps, instituting sweeping changes. His ironclad mandates reshaped officers into disciplined servicemen—clean, tidy, dedicated. Under his command, they became effective.

With disciplined ranks, Patton significantly impacted Allied efforts in North Africa. As his reputation grew, the Allies needed him elsewhere. He was reassigned to Operation Husky in Sicily. There, he faced brutal weather and still achieved objectives with 90,000 men.

– Operation Husky and Controversies

Patton’s ambitions led to repeated friction during the Sicily campaign. He clashed with Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. and Theodore Roosevelt Jr. He even lost a message meant to restrain his actions, acting before reading it. In July 1943, his men slaughtered 71 Italian and two German POWs without cause.

Patton helped cover up the atrocity to avoid bad press. The truth emerged later, but he avoided blame for complicity. During the campaign, he slapped two soldiers suffering from battle fatigue—now understood as PTSD. He called them cowards and ordered them back to the front, even threatening one with execution.

Eisenhower punished him for this behavior, forcing both private and public apologies. Patton was denied a field command for nearly a year. Eisenhower viewed him as impulsive and error-prone. Action was required to protect the war effort.

Patton was reassigned to the Third Army in England to train inexperienced officers. But there was another purpose behind his posting. The Germans feared Patton more than any Allied general and assumed he led the main invasion force. Their fixation on him distracted from the true plan: Normandy.

Patton missed D-Day but soon joined the invasion with the Third Army. Coordinating with other corps, he delivered significant progress. His tactics emphasized speed, aggression, air support, and recon. Logistically, his army stayed exceptionally well-informed.

– Lorraine and Critiques

Patton’s ego began to exact a toll. While the Third Army succeeded often, other commanders questioned his decisions—and so did enemies. One German officer, initially impressed, was baffled by the Lorraine campaign’s heavy casualties with little gain. Patton’s rigid adherence to plan overshadowed the human cost.

From September to November 1944, Lorraine saw over 50,000 casualties—one-third of the force. Historian Carlo D’Este called Lorraine Patton’s biggest failure, despite its technical success. Patton demanded resources that strained Allied priorities. The question remained: was the prize worth the price?

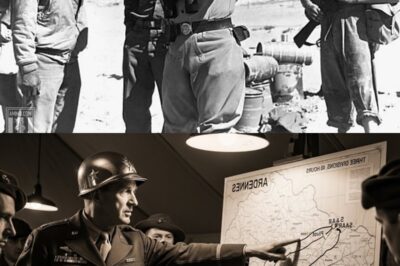

– The Battle of the Bulge

Patton’s greatest tactical moment came during the Battle of the Bulge. First, he had to disengage the Third Army from combat in Germany. Fortunately, he had already prepared three contingency plans. After the Allied conference, he called his staff and said two words: “Play ball.”

Six divisions and over 133,000 vehicles mobilized immediately. Patton’s Third Army reached Bastogne just in time. They enabled relief and resupply for trapped Allied forces. Patton declared the maneuver his outstanding wartime achievement.

After the Bulge, the Allies pushed to keep Germany retreating. Patton proposed action, but logistics starved the Third Army. He responded with audacity: his men posed as First Army to requisition fuel. Thousands of gallons powered his tanks deeper into enemy territory.

Despite shortages, the Third Army carved a massive path through Germany. They dismantled the First and Seventh German armies. During this advance, Patton was ordered to bypass Trier—allegedly needing twice the troops to take it. His reply became legend.

As the Third Army pressed forward, Patton planned a rescue of POWs near Hammelburg. He had a personal stake: his son-in-law was among them. He sent a task force to liberate the camp behind German lines. The mission went disastrously wrong.

Fifty-seven vehicles were lost. Of 314 men sent, only 35 returned. Even Patton admitted it was a bad decision. Ambition had outrun prudence, with grievous consequences.

– Aftermath and Legacy

Despite setbacks, the Third Army remained one of the Allies’ most successful units. They spent 281 days in continuous action and seized 32,763 square miles of German-occupied territory. Patton had reasons to be proud when World War II ended in 1945. The following year, he finally rested after a grueling campaign.

After traveling to Paris and London, he returned to Bedford, Massachusetts, greeted by crowds. He spoke at Hatch Memorial Shell to 20,000 people. Among them were 400 wounded Third Army veterans. Patton’s remarks drew controversy.

He said men killed in action were “frequently a fool” and declared the wounded the real heroes. It was a jarring sentiment for a public figure. Patton struggled in civilian life. He later wrote, “Yet another war has come to an end, and with it my usefulness to the world.”

Depression deepened without combat’s focus. He made horrific comments about Jews, calling them “locusts,” “lower than animals,” and a “subhuman species.” By late 1945, his mood was dismal. To distract him, Hobart Gay planned a hunting trip near Speyer, Germany.

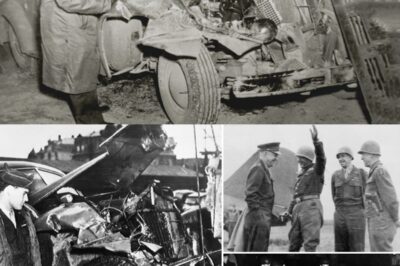

Driving along, they passed rotting, abandoned cars. “How awful war is,” Gay said. “Think of the waste.” Then a U.S. Army truck struck their 1938 Cadillac limousine. Gay and the driver remained mostly unharmed; Patton did not.

Patton suffered a head cut, breathing difficulty, a compression fracture, and dislocation of two vertebrae in his neck. He was paralyzed from the neck down. Hospitalized in traction, he was told life would not return to normal. Only his wife Beatrice was allowed to visit.

“This is a hell of a way to die,” he said. On December 21, he succumbed to pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure at age 60. He was buried in Luxembourg among Third Army casualties, per his wishes. His legacy remains powerful—and deeply flawed.

Over the years, Patton continued to see Jean Gordon—first in London in 1944, then Bavaria in 1945. He spoke openly about the affair, and the family knew. When his wife discovered he was still consorting with his niece by marriage, she left. He begged forgiveness, an unusual act for him.

His daughter Ruth Ellen denied the romance while alive. After her death, her writings revealed the family understood the relationship as romantic. Jean Gordon returned to the U.S. after Patton’s death, shattered. In January 1946, she was found in a friend’s apartment, asphyxiated by a gas stove left on.

– Outro

If you enjoyed this story, give it a thumbs up and subscribe for more. Consider joining our membership for early access, priority replies, and input on future content—your support keeps the channel going. Thank you for watching, and we’ll see you next time.

“I’m trying to bring back to you what these soldiers have given. God damn it, it’s no fun to say to men that you love, ‘Go out—go out and get killed.’ And we’ve had to say it, and by God, they have gone, and they have won. But remember: the sacrifice these men have made must not be in vain.”

News

Why Patton Was the Only General Who Predicted the German Attack

– December 9, 1944. A cold Monday morning at Third Army headquarters in Nancy, France. Colonel Oscar Koch stood before…

What German High Command Said When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

– “Impossible. Unmöglich.” That word echoed through German High Command on December 19, 1944. American General George S. Patton had…

Patton (1970) – 20 SHOCKING Facts They Never Wanted You to Know!

– Behind the Academy Award-winning classic Patton lies a battlefield of secrets. What seemed like a straightforward war epic is…

Was General Patton Silenced? The Death That Still Haunts WWII

Was General Patton MURDERED? Mystery over US war hero’s death in hospital 12 days after he was paralyzed in an…

Patton’s Assassin Confessed – He Was Paid $10,000

September 25, 1979, Washington, D.C. The Grand Ballroom of the Hilton sat in shadow—450 living ghosts at round tables under…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

June 1979, Newport Beach, California. Four days after John Wayne’s funeral, the house felt hollow—72 years of life reduced to…

End of content

No more pages to load