August 17th, 1944.

The morning mist clings to the abandoned airfield outside Chartres, France. In a makeshift Wehrmacht repair depot, three German mechanics huddle around a peculiar sight: a captured American truck unlike anything they have encountered in four years of war. Obergefreiter Klaus Hoffman runs his oil-stained fingers along the truck’s massive rear axle, tracing the thick drive shafts that connect to all six wheels. His weathered face betrays confusion. For two decades, he has repaired every German military vehicle from motorcycles to halftracks, yet this machine defies everything he knows about automotive engineering.

*Unmöglich*, he whispers to his companions. Impossible.

The truck before them is a GMC CCKW 353—what the Americans call their “deuce and a half.” Its olive drab paint bears scars from recent combat, but the mechanical components remain intact. What disturbs Hoffman most is not the truck’s size or apparent durability. It is the realization dawning in his mind as he examines the front axle. This American machine can send power to all six wheels simultaneously.

In the deepest mud, the steepest incline, or the most treacherous terrain, this truck would never stop moving. The implications terrify him more than any Allied bomber formation ever could.

The German Wehrmacht entered World War II with a transportation philosophy rooted in 19th‑century military tradition. Horse-drawn wagons remained the backbone of German logistics, supplemented by a modest fleet of trucks that reflected the automotive industry’s pre-war limitations. German military planners, obsessed with the romantic notion of lightning warfare, focused their engineering brilliance on tanks and aircraft while treating trucks as mere afterthoughts.

The Opel Blitz, Germany’s most common military truck, embodied this short-sighted approach. Its 3.6L 6‑cylinder engine produced a modest 75 horsepower. The Blitz could haul 3.5 tons on good roads. Its rear‑wheel drive configuration performed adequately on paved surfaces but became helplessly mired in anything resembling challenging terrain.

German engineers had designed it for the smooth autobahns of the Fatherland, not the muddy steppes of Russia or the bombed‑out roads of occupied Europe. By 1942, the Wehrmacht’s logistical shortcomings became glaringly apparent. During the advance towards Stalingrad, entire divisions ground to a halt not from enemy resistance, but from their inability to move supplies forward. German trucks, designed for civilian comfort rather than military necessity, broke down with alarming frequency.

Their narrow tires sank into mud. Their low ground clearance caught on obstacles. Their rear‑wheel drive systems spun helplessly when traction disappeared. Mercedes‑Benz offered the L3000, a slightly more robust alternative, but it suffered from identical fundamental flaws. German automotive engineers—brilliant in precision and craftsmanship—had failed to grasp a basic military truth. Wars are won by the side that can move men and materials most effectively, not by the side with the most elegant engineering solutions.

The German military’s reliance on horses revealed the depth of this miscalculation. While panzer divisions captured headlines with dramatic advances, the vast majority of German infantry divisions depended on 750,000 horses for transportation. These animals required fodder, veterinary care, and rest—luxuries unavailable in the vast expanses of the Soviet Union. As winter approached in 1941, German logistics officers watched helplessly as their magnificent war machine began to starve.

Across the Atlantic, American engineers approached the challenge of military transportation with an entirely different philosophy. When President Roosevelt signed the Lend‑Lease Act in March 1941, he unleashed not just American industrial capacity, but a fundamentally superior understanding of what modern warfare demanded. American truck manufacturers, led by General Motors and Studebaker, had spent decades perfecting vehicles for the rugged terrain of the American frontier.

The GMC CCKW emerged from this practical tradition. General Motors engineers, drawing on experience building trucks for logging companies and construction crews, created a machine designed to conquer any terrain. The CCKW’s six‑wheel drive system represented a revolutionary leap forward in automotive technology. Unlike German trucks that sent power only to their rear wheels, the American design could engage all six wheels simultaneously, distributing weight and traction across the entire vehicle.

Studebaker’s US6 took this concept even further. With its Hercules JXD six‑cylinder engine producing 87 horsepower and its sophisticated transfer case system, the US6 could climb grades that would defeat any German vehicle. More importantly, American engineers solved the fundamental problem that plagued European military trucks: how to maintain mobility in conditions where roads ceased to exist. The answer was not elegance—it was brute, reliable capability.

The scale of American production dwarfed anything Germany could imagine. By 1943, American factories were producing over 800,000 military vehicles annually. The Willow Run plant alone, converted from automobile production, could complete a new truck every 63 seconds. German planners, accustomed to thinking in terms of hundreds or thousands of vehicles, could not comprehend an industrial system capable of producing military equipment by the hundreds of thousands.

American Lend‑Lease shipments began reaching Allied forces in 1942, carrying with them a technological revelation that would reshape modern warfare. The Soviet Union received 152,000 American trucks through the treacherous Arctic convoys and the Persian Corridor. British forces in North Africa replaced their unreliable vehicles with American‑built GMCs and Dodges. Each delivery carried not just machines, but a new understanding of what mechanized warfare could accomplish.

By 1943, American trucks were operating on every front where Allied forces fought. Their superiority became immediately apparent—not just in mechanical reliability, but in their fundamental capability to maintain operations regardless of terrain or weather conditions. German intelligence officers analyzing captured Allied equipment began filing reports that disturbed the highest levels of Wehrmacht command.

The first German mechanics to examine captured American trucks experienced what can only be described as technological culture shock. Feldwebel Werner Schultz, a veteran automotive specialist who had maintained German vehicles since the Polish campaign, later wrote in his diary about encountering a Studebaker US6 in Tunisia. His words reveal the profound disorientation of discovering that the enemy possessed fundamentally superior technology.

“Today I examined the American truck we captured near Kasserine,” Schultz wrote in March 1943. “Everything about this machine contradicts what we have been taught about proper engineering. The engine is larger than necessary, the transmission more complex than required, and the entire vehicle built to standards that seem wasteful. Yet when I engaged the front axle and tested the vehicle in sand, it performed like nothing we possess.”

“Our Opel trucks would be helpless in such conditions,” he admitted. From a technical perspective, the gap between German and American truck technology resembled the difference between 19th‑ and 20th‑century engineering philosophy. German vehicles prioritized efficiency and precision—admirable qualities for civilian use, but devastating limitations in wartime conditions.

The Opel Blitz weighed 3,100 kg empty and could carry 3,500 kg of cargo, achieving what German engineers considered optimal weight‑to‑payload ratios. American trucks deliberately sacrificed such mathematical elegance for practical capability. The GMC CCKW weighed 5,200 kg empty, but could haul 2,500 kg across terrain that would immobilize any German vehicle. On paper, it looked “wasteful.” In reality, it was unstoppable.

More significantly, American trucks incorporated redundancy systems that German engineers considered extravagant. If one axle failed, American trucks could continue operating. If traction disappeared on one set of wheels, power could transfer to wheels with better grip. What looked like over‑engineering in a laboratory became life‑saving reliability in mud, snow, and sand.

The human stories emerging from these encounters reveal the psychological impact of technological inferiority. Gefreiter Hans Müller, captured during the Battle of the Bulge, spent three months in an American POW camp where he watched endless convoys of American trucks supplying Allied forces. His letters home, intercepted by German censors, described his growing realization that Germany was fighting an enemy with unlimited mechanical resources.

“They have trucks that can climb mountains,” Müller wrote to his wife in January 1945. “I have seen American vehicles crossing streams that would trap our best halftracks. These machines never seem to break down, never seem to struggle, never seem to stop. How can we compete against such abundance?”

The strategic implications became clear to German commanders who understood logistics. General Heinz Guderian, architect of German armored doctrine, privately acknowledged that American truck technology represented a revolutionary advance in military mobility. In captured German staff documents, analysts repeatedly referenced American transportation superiority and filed urgent requests for vehicles capable of matching Allied logistical capabilities.

The production scale behind American truck manufacturing represented an industrial achievement German planners found impossible to comprehend. While Germany struggled to produce 46,000 military trucks in 1943, American factories delivered 621,000 vehicles to Allied forces. The Studebaker plant in South Bend, Indiana, operating around the clock with three shifts, could complete more trucks in a single month than the entire German automotive industry produced in a year.

Soviet forces received the most dramatic transformation through American truck deliveries. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, commanding Soviet forces during the final push to Berlin, later acknowledged that American trucks fundamentally changed the Red Army’s operational capabilities. Before Lend‑Lease deliveries began, Soviet infantry divisions moved at walking pace, limited by dependence on horse‑drawn transport and inadequate wheeled vehicles.

The arrival of American trucks mechanized the Red Army almost overnight. Soviet commanders discovered they could move entire divisions hundreds of kilometers in days rather than weeks. Artillery units, previously static once positioned, gained unprecedented mobility. Supply lines that had collapsed under the strain of feeding millions of soldiers suddenly functioned with mechanical precision.

From a tactical perspective, American trucks provided Allied forces with operational advantages German commanders could not counter. The Red Ball Express, established after the Normandy invasion, demonstrated this superiority on a massive scale. Operating from August through November 1944, this truck convoy system transported 412,393 tons of supplies to advancing Allied forces.

The operation required 5,958 trucks driving continuously over 700 km of French roads, delivering everything from ammunition to gasoline to the front lines. German intelligence officers monitoring Allied supply operations filed increasingly desperate reports about their inability to disrupt this mechanical river of supplies. Traditional methods of interdicting enemy logistics—destroying bridges, mining roads, attacking supply depots—proved ineffective against an enemy whose trucks could bypass obstacles, traverse damaged terrain, and operate independently of fixed infrastructure.

The moral dimension of this technological gap cannot be understated. German soldiers witnessing endless streams of American vehicles began questioning their leadership’s competence and their nation’s industrial capabilities. Propaganda about German technological superiority rang hollow when confronted with machines that clearly surpassed anything the Fatherland could produce.

American truck drivers—many of them African‑American soldiers serving in segregated units—became unlikely symbols of Allied technological dominance. These men, driving massive six‑wheel drive vehicles through conditions that would defeat German transport, demonstrated daily that America possessed not just superior equipment, but superior manufacturing systems, superior engineering philosophy, and superior understanding of modern warfare’s logistical requirements.

September 1944 marked the moment when German military leadership could no longer ignore the catastrophic implications of American truck superiority. General Omar Bradley’s forces, supported by the Red Ball Express, had advanced 600 km in 26 days—a rate of movement German logistics officers declared impossible based on their own transportation limitations. Wehrmacht intelligence reports from this period reveal growing panic about Allied mobility advantages.

The decisive revelation came during Operation Market Garden, when German forces observed American supply operations supporting the airborne assault on Arnhem. Oberst Friedrich von der Heydte, commanding German paratroopers defending the region, watched in amazement as American trucks continued delivering supplies despite constant artillery bombardment and air attacks.

His post‑battle report to Army Group B headquarters described scenes that fundamentally challenged German understanding of military logistics. “The enemy’s transportation system operates with mechanical perfection,” von der Heydte wrote. “Their trucks traverse terrain our vehicles cannot enter, carry loads our machines cannot handle, and maintain schedules our logistics officers consider fantasy. We have destroyed their bridges, cratered their roads, and targeted their supply columns. Yet these vehicles continue advancing as if obstacles do not exist.”

The psychological impact on German commanders became apparent in intercepted communications from this period. General Walter Model, commanding Army Group B, privately confessed to his staff that German forces faced an enemy with unlimited mechanical mobility. His assessment, captured in Soviet intelligence files after the war, revealed the desperation of German military leadership confronting American industrial supremacy.

At the tactical level, individual encounters between German and American forces demonstrated this technological gap with brutal clarity. During the Battle of the Bulge, German armored spearheads advanced rapidly through the initial surprise attack, but quickly outran their supply lines. German trucks, struggling through snow and mud, could not maintain the pace required for sustained offensive operations.

American forces, falling back under German pressure, evacuated supplies and repositioned equipment using their superior truck fleets. Within 72 hours, American logistics officers had redirected massive supply columns to support defensive positions and counterattack preparations. German commanders, accustomed to weeks of preparation for major supply movements, watched helplessly as American forces accomplished logistical “miracles” in days.

The climactic moment came on December 26th, 1944, when General Patton’s Third Army—supported by 1,400 trucks carrying fuel and ammunition—relieved the surrounded garrison at Bastogne. This operation required moving an entire army 150 km in winter conditions while maintaining full combat capability. German staff officers analyzing this achievement after their defeat concluded that American truck technology had rendered traditional military logistics obsolete.

The Eastern Front provided the most devastating demonstration of American truck superiority’s strategic implications. By January 1945, Soviet forces equipped with 154,000 American trucks launched the Vistula–Oder offensive, covering 500 km in 23 days and reaching within 100 km of Berlin. German defenders, still dependent on horse‑drawn transport and inadequate wheeled vehicles, could not retreat fast enough to establish defensive positions.

Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev, commanding the 1st Ukrainian Front during this offensive, later described the transformation American trucks brought to Red Army operations. His forces, previously limited to carefully planned advances with extensive preparation periods, suddenly possessed the mobility to exploit breakthroughs immediately. American trucks allowed Soviet commanders to maintain pressure on retreating German forces without pause for logistical consolidation.

German Army Group Center, defending against this mechanized avalanche, faced annihilation not from superior Soviet tactics, but from their inability to move supplies and reinforcements at the pace modern warfare demanded. Wehrmacht logistics officers filing their final reports from this period described watching Soviet truck columns advancing at speeds German forces could not match even in retreat.

The technological revelation reached its peak during the final battle for Berlin. American‑supplied trucks enabled Soviet forces to maintain three separate army groups in simultaneous offensive operations around the German capital. Each army group required thousands of tons of ammunition, fuel, and supplies daily—logistical demands that German forces could no longer comprehend, much less counter.

Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici, commanding Army Group Vistula during the final defense of Berlin, recognized that German defeat resulted not from tactical inferiority but from fundamental technological disadvantage. His memoirs, written after the war, acknowledged that American truck technology had rendered German military doctrine obsolete. “We fought like medieval knights against machine‑age warriors,” Heinrici wrote. “Our courage and tactical skill meant nothing against an enemy that could move faster, supply better, and sustain longer than anything we could imagine.”

The moment of complete realization came on April 25th, 1945, when American and Soviet forces met at Torgau on the Elbe River. German observers witnessing this meeting between mechanized armies, supported by thousands of identical American trucks, understood that they had been defeated by industrial capacity rather than battlefield maneuver. The war’s outcome had been determined not on front lines but in factories—American factories capable of producing military vehicles in quantities that dwarfed German imagination.

Captain Wilhelm Keitel, son of the Wehrmacht’s field marshal, served as a liaison officer during the final weeks of fighting. His diary entries from this period capture the psychological devastation of confronting technological obsolescence. “Today, I counted 847 American trucks in a single Soviet supply column,” Keitel wrote on April 20th, 1945. “These machines represent industrial might we cannot match, engineering philosophy we do not understand, and military capability we cannot counter.”

The immediate aftermath of Germany’s defeat revealed the full extent of American truck technology’s impact on Wehrmacht thinking. During the occupation period, Allied intelligence officers discovered extensive German research programs attempting to reverse‑engineer captured American vehicles. These efforts, hidden in underground facilities and dispersed research centers, demonstrated desperate attempts to understand and replicate American automotive superiority.

At the Mercedes‑Benz facility in Stuttgart, American investigators found detailed technical drawings of the GMC CCKW’s transfer case system. German engineers had disassembled multiple captured American trucks, photographed every component, and attempted to recreate the sophisticated mechanisms that enabled all‑wheel drive capability. Their notes, written in precise technical German, revealed both admiration for American engineering and frustration at their inability to duplicate it with available materials and manufacturing techniques.

The Opel plant in Brandenburg yielded even more revealing evidence of German technological desperation. Engineers there had developed prototype vehicles incorporating design elements copied from American trucks—wider tires, reinforced frames, improved ground clearance, and experimental all‑wheel drive systems. However, German industry’s wartime limitations prevented these improvements from reaching production.

Critical materials like high‑grade steel and synthetic rubber remained unavailable, while precision manufacturing equipment had been destroyed by Allied bombing. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, Germany’s most celebrated automotive engineer, privately acknowledged American technological superiority in documents captured after the war. His technical assessment of the Studebaker US6, written in March 1945, praised the American vehicle’s systematic approach to mechanical reliability and intelligent integration of complex drive systems.

Porsche’s analysis concluded that the German automotive industry would require a fundamental reorganization of engineering philosophy to match American capabilities. German soldiers returning from captivity brought firsthand accounts of American industrial capacity that further demoralized civilian populations. Former Wehrmacht truck drivers who had struggled to maintain aging Opel Blitz vehicles throughout the war described American motor pools containing thousands of identical, perfectly maintained vehicles.

These accounts spread through German communities, reinforcing the population’s growing understanding that their nation had fought an unwinnable industrial war. The psychological impact extended beyond technical admiration to fundamental questioning of German engineering traditions. For decades, German automotive manufacturers had prided themselves on precision craftsmanship and elegant solutions to mechanical problems.

The discovery that American “wasteful” engineering approaches produced superior military vehicles challenged core assumptions about technological development. Wehrmacht maintenance records preserved in military archives documented the practical consequences of this technological gap. German truck availability rates averaged 60% throughout 1944, meaning four out of every ten vehicles remained non‑operational due to mechanical failures.

American truck availability rates, by contrast, consistently exceeded 85%, despite operating in identical combat conditions. The war’s end brought immediate recognition that American truck technology had fundamentally altered the nature of modern warfare. European military planners, surveying the devastation and analyzing the conflict’s lessons, concluded that future armies would require mechanized logistics systems capable of matching American standards.

Traditional military transportation—horses, bicycles, and limited truck fleets—had proven obsolete against enemies possessing virtually unlimited mechanical mobility. France initiated the most comprehensive transformation, adopting American military vehicles wholesale for its reconstructed armed forces. French commanders, having witnessed German defeat through superior Allied logistics, insisted their military must never again depend on inadequate transportation systems.

By 1947, French forces operated entirely American‑designed vehicles, from jeeps to heavy cargo trucks, abandoning centuries of military transportation tradition. The Soviet Union pursued a different approach, using captured American trucks as templates for domestic production while maintaining the façade of indigenous technological development.

Soviet engineers, working with detailed measurements and photographs of Lend‑Lease vehicles, created the ZIL‑157 and similar trucks that closely replicated American design principles. Stalin’s regime could not publicly acknowledge technological dependence on capitalist enemies, but Soviet military vehicles from this period clearly demonstrated American influence.

Britain faced the most difficult adjustment, as the traditional British automotive industry lacked the capacity to produce vehicles matching American standards. British military planners, analyzing their wartime experience, concluded that future conflicts would require either continued dependence on American suppliers or fundamental reconstruction of domestic manufacturing capabilities. The decision to maintain close military ties with the United States partly reflected this technological reality.

German automotive manufacturers, operating under Allied occupation, began incorporating American design principles into civilian vehicle production. Mercedes‑Benz engineers, applying lessons learned from captured American trucks, developed new civilian models featuring improved reliability, simplified maintenance procedures, and enhanced all‑terrain capability. These vehicles, while marketed for civilian use, clearly reflected military technology transfer from American sources.

The broader implications extended far beyond automotive engineering to fundamental questions about industrial organization and technological development. American truck superiority had resulted not from individual engineering brilliance, but from systematic integration of design, manufacturing, and quality control processes. European industries, traditionally organized around craft production methods, recognized they had to adopt American mass production techniques to remain competitive.

Militaries worldwide revised their logistics curricula to emphasize mechanized transportation systems. Staff colleges that had previously taught horse‑drawn supply operations now focused on truck convoy management, mechanical maintenance procedures, and the strategic implications of superior mobility. The American truck had transformed military education as thoroughly as it had transformed warfare itself.

By 1950, NATO standardization agreements mandated that member nations maintain truck fleets capable of interoperating with American forces. This requirement effectively imposed American design standards on European military vehicles, ensuring that future conflicts would not repeat the technological disparities that had doomed German logistics. The American truck had become the template for modern military transportation worldwide.

The German mechanics examining the captured GMC truck in August 1944 witnessed more than superior engineering. They glimpsed the future of mechanized warfare. Their shocked recognition that American trucks could traverse impossible terrain without stopping represented a profound moment of technological revelation that would reshape military thinking for generations.

The story of American truck superiority illuminates a fundamental truth about modern conflict. Wars are won not by the most courageous soldiers or the most brilliant generals, but by nations possessing superior industrial systems and technological integration. Germany’s defeat resulted from a systematic failure to understand that 20th‑century warfare demanded mass production capabilities, relentless logistics, and machines that could keep moving when everything else stopped.

News

“Never Seen Such Men” – Japanese Women Under Occupation COULDN’T Resist Staring at American Soldiers

For years, Japanese women had been told only one thing about the enemy. That American soldiers were merciless. That surrender…

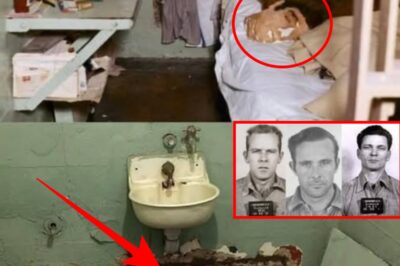

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

End of content

No more pages to load