They called me defective during toteminovida, and by 19—after three doctors examined my frail body and delivered their verdict—I started to believe them. My name is Thomas Bowmont Callahan. I was born premature in January 1840, arriving two months early in one of Mississippi’s coldest winters. The midwife, Mama Ruth, said I wouldn’t live through the night, but my mother held me and whispered that my weak heart was fighting—and she was right.

Survival wasn’t thriving. At one month, I weighed barely six pounds; at six months, I couldn’t hold up my head; at one year, I could barely sit upright. Doctors said my premature birth had stunted me for life. My mother died of yellow fever when I was six, leaving me a promise: that strength could be found in mind, heart, and soul—even when the body failed.

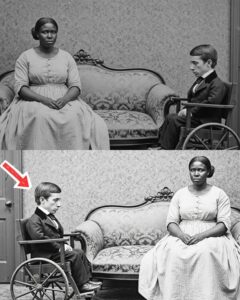

My father, Judge William Callahan, was everything I wasn’t—tall, broad-shouldered, and forceful. He built Callahan Plantation into an 8,000-acre empire overlooking the Mississippi River, with a mansion of white brick and Doric columns, and quarters where 300 enslaved people lived in stark contrast. I grew up in this world, tutored at home, too frail for school, learning languages, mathematics, and philosophy in my father’s library.

By 19, I was five-foot-two and 110 pounds, with a birdlike skeleton, a caved-in chest, trembling hands, and terrible eyesight behind thick spectacles. My voice never fully deepened, my hair was thinning, my skin translucent. Worst of all, I lacked any masculine development—sterile, with underdeveloped reproductive organs. The examinations began after my 18th birthday, following a failed marriage prospect.

Dr. Harrison, Yale-trained, conducted a humiliating exam and declared hypogonadism—permanent sterility. Dr. Blackwood in Vicksburg agreed. Dr. Merier from New Orleans, gentle but direct, confirmed I would never father children. The verdict spread quickly through planter society—no bride would accept a husband who couldn’t give heirs.

Rejections multiplied, and public comments cut deep: pity at church, drunken “nature’s way” remarks, comparisons to horses and “failed breeding.” My father retreated, distant and desperate, while I lost myself in books—Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Keats, Shelley—and forbidden abolitionist writings. The reality of slavery’s brutality began to pierce the comfortable world I’d taken for granted.

In March 1859, my father confronted me after months of failed proposals. He declared a “creative” solution: he would give me to Delilah, a prime field hand, as my companion. He planned to breed her with a strong enslaved man from another plantation, then legally adopt and free the children to become my heirs. He would use the law to craft an inheritance from human bodies.

I refused. I told him the plan was evil—breeding a woman like livestock, using legal fictions to manipulate lives. He insisted enslaved people were property in the eyes of the law and her opinion was irrelevant. Something in me snapped. I would not participate. The argument ended with shattered glass and a vow to act.

Delilah was 24, nearly six feet tall, powerful and intelligent—worth “three regular hands,” the overseers said. I could do little legally, but I could warn her. In her cabin, I told her my father’s plan—my sterility, the breeding scheme, the forced motherhood. Shock turned to weary resignation. She asked why I was telling her. I said that sometimes stopping one evil is all one can do.

Escape seemed impossible—patrols everywhere, no papers, no money, no connections. But I had a trust fund, access to my father’s documents, and the ability to forge travel passes. I suggested we leave together—north to Ohio. She questioned my motives, the risks, and the consequences. I told her I would give up everything to save one person—and to escape complicity.

She agreed to try, asking for two days to prepare quietly. I wrote letters—goodbye to friends, thanks to Dr. Harrison, and a final letter to my father. I told him I was leaving, that slavery was evil, and that I would not help build a legacy on breeding and ownership. I left him the truth: my dignity would not be preserved by participating in harm.

At midnight, we met at the stable. I had money, supplies, forged passes. We headed northeast, avoiding Natchez, aiming for Vicksburg, Tennessee, and ultimately Cincinnati. We traveled by night, hid by day, and used forged passes at checkpoints. Each time a patrol examined them, I kept calm—until we were safely out of sight.

Delilah’s skills kept us alive. She fixed a wagon wheel, waded streams, found edible plants, set snares, and remembered lessons from her father before he was sold away. We talked about slavery’s cruelty, my isolation and shame, and the growing realization that my life was built on suffering. She told me I wasn’t defective—just different. Society was wrong about slavery, women, and me.

By Tennessee, something shifted—companion became partner. In an abandoned barn during a storm, she asked what would become of us if we reached freedom. I promised she would owe me nothing. She chose to stay—with me. We kissed, not as master and slave, but as two people choosing each other against a world built to keep them apart.

We reached Cincinnati in early June. We rented a small house in a mixed neighborhood and presented ourselves as husband and wife—Thomas and Delilah Freeman. Money was tight; I clerked in a law office, she sewed as a seamstress. People stared, judged, misunderstood. But we built a life on choice rather than ownership.

We married in November 1859 before a Quaker minister who recognized our union, even if the state did not. “I take you, Delilah Freeman, to be my wife,” I said. “I take you, Thomas Callahan Freeman, to be my husband,” she replied—adding my name to hers. We were married in truth, bound by love and shared freedom.

The war came in 1861. We couldn’t fight, but our home became a stop on the Underground Railroad. Delilah guided newly escaped people, and I helped with documentation. We met Frederick Douglass, who praised us both for choosing freedom—hers from ownership, mine from the limitations imposed by society. He reminded us that freedom is about choice, not circumstance.

We never had biological children, but in 1865 we adopted three—formerly enslaved children whose parents were lost in the chaos. We named them Sarah, Frederick, and Liberty. We raised them in freedom, taught them to read and write, and sent them to schools that accepted Black children. We taught them that worth is defined by character and choice.

Sarah became a teacher for freed slaves. Frederick became a doctor serving Cincinnati’s Black community. Liberty became a civil rights lawyer who fought segregation and used the law to dismantle oppression. They lived the values we had chosen: dignity, justice, and love born out of defiance.

I lived longer than expected—22 years beyond the doctors’ predictions—and died of pneumonia in 1882 at age 42. Delilah held my hand. I asked if it was worth it—leaving everything, bringing her north. She told me I’d given her freedom, dignity, love, and children who would grow up free. It had been worth everything.

Delilah died in 1900 at 65, after years spent fighting for civil rights and teaching young people about choosing justice over comfort. We are buried together in Spring Grove Cemetery under a shared headstone: Thomas Bowmont Callahan Freeman (1840–1882) and Delilah Freeman (1835–1900), married 1859. We chose freedom over comfort, love over convention.

Our children lived lives of service—Sarah’s school educated over a thousand freed slaves, Frederick’s practice served for 40 years, Liberty’s legal work dismantled segregation. In 1920, Liberty published From Property to Partnership: The Story of Thomas and Delilah Freeman. It told how a “defective” white man and an enslaved woman found freedom and love by rejecting imposed labels.

Records document our lives: my birth in 1840, examinations in 1858, trust fund withdrawals in 1859, Delilah’s sale in plantation ledgers from 1850, Cincinnati directories listing our work, the Quaker ceremony, adoption papers, and our gravestone. Our story challenges assumptions about disability, race, and worth—asserting that value lies in moral courage and chosen dignity.

Judge Callahan’s plan—meant to preserve his legacy—sparked something deeper. Two people rejected ownership and breeding, choosing partnership and freedom. If this story moves you, share it. Remember that history is filled with those who defied impossible odds and chose justice over convenience. Labels don’t define us. Our choices do.

Their legacy endures in descendants who work for justice, in the example of choosing morality, and in the reminder that every person deserves freedom, dignity, and the chance to write their own story. It is a testament to the truth that human worth transcends physical ability and legal status—and that love and freedom can triumph even in the darkest times.

News

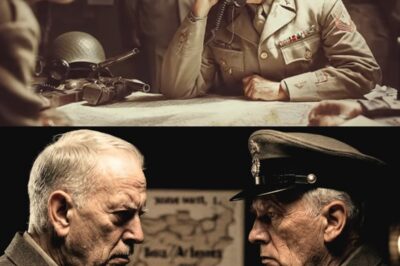

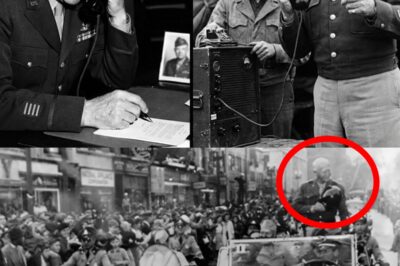

What MacArthur Said When Patton Died…

December 21, 1945. Tokyo, Japan. General Douglas MacArthur sits in his office in the Dai-ichi Seimei Building—the headquarters from which…

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne

If Patton hadn’t moved in time, the 101st Airborne wouldn’t have been captured or forced to surrender. They would have…

The Phone Call That Made Eisenhower CRY – Patton’s 4 Words That Changed Everything

December 16, 1944. If General George S. Patton hadn’t made one phone call—hadn’t spoken four impossible words—the United States might…

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

End of content

No more pages to load