April 1945, a muddy prison camp near Koblenz, Germany. Thirty‑four German women sat on wooden benches. Their uniforms were torn, their faces hollow. They had not eaten a real meal in weeks. Then an American soldier walked up and handed them something yellow.

Corn. Grilled corn cobs dripping with butter. The women stared in horror. One of them whispered, “They are feeding us pig food.” Another said, “This is what animals eat.” They refused to touch it.

They pushed their trays away. Some women looked like they wanted to cry. But here is the strange part: within one hour, these same women were laughing. They were licking butter from their fingers. They were asking for more.

What happened in that one hour? What made them change their minds so quickly? And why did a simple cob of corn shatter everything they believed about their American enemy? This story is not in your history books, but it is true.

It is a story about war, about food, and about the moment when two worlds collided over a dinner plate. Stay with me until the end because what these women discovered will surprise you. And what they carried home after the war will change how you think about enemies, about propaganda, and about the power of a shared meal.

If you love real stories from history, hit that subscribe button right now. Help us bring more forgotten stories like this one to life. Tap the like button to support this channel and watch until the very end, because the best part of this story is still coming. Now let us go back to April 1945.

The war was almost over. Germany was falling, and 34 women were about to learn that everything they believed was a lie. It all started with a cob of corn.

Collapse and Capture

The spring of 1945 did not arrive gently in Germany. It came with the grinding roar of Sherman tanks, the distant percussion of artillery barrages, and the acrid stench of burning cities that hung in the air for miles. By March, the Western Allies had crossed the Rhine.

By April, the Reich was hemorrhaging territory faster than its commanders could redraw their maps. Caught in the current of this collapse were thousands of women—not soldiers in the traditional sense, not combatants, but uniformed members of the German war machine nonetheless.

They were Luftwaffe communications auxiliaries, Wehrmacht telephone operators, anti‑aircraft battery helpers, military nurses, and administrative clerks. Women who had signed up or been conscripted to free men for the front lines. Women who believed, many of them, that they would never see the enemy face to face.

By April 1945, an estimated 500,000 German women were serving in military auxiliary roles across the Reich. Of these, approximately 12,000 to 15,000 would be captured by American forces in the war’s final weeks. Analise Bräunig was one of them.

She was 23 years old, a signals auxiliary stationed near Cologne. She had spent the war routing communications through a switchboard in a concrete bunker that smelled of copper wiring and stale cigarette smoke. She had never fired a weapon. She had never seen a dead body—until the bombing raids began.

On April 7th, her unit received orders to retreat eastward. By April 9th, those orders were meaningless. American infantry had encircled their position. Analise and 33 other women surrendered in a muddy farmyard, their hands raised, their gray‑blue auxiliary uniforms splattered with the filth of roads they had walked for three days straight.

“I thought they would shoot us,” she would later recall in a 1987 interview with the German oral history project *Stimmen der Generation*. “That is what we had been told—that the Americans were barbarians, that they would not spare women.”

They were not shot. Instead, a young American sergeant with a drawling accent she could not place—Staff Sergeant Virgil Thibodeaux, a Cajun from Lafayette, Louisiana—gestured for them to sit beside a hedgerow while his men secured the farmhouse. He offered them water from his own canteen.

Analise noticed that his hands were steady, his voice calm. There was no malice in his eyes. The paradox struck her immediately. This was the enemy—this soft‑spoken man who smelled of tobacco and machine oil, who handed out canteens as if they were guests rather than prisoners.

Elsewhere across the collapsing front, similar scenes unfolded. Waltrud Pfeifer—“Trudi” to her friends—was captured near Aachen, a sharp‑tongued telephone operator from Berlin. She had spent the final weeks of the war convinced that surrender meant execution.

When American soldiers instead handed her a blanket and a tin cup of coffee, she wept. She could not understand it. Elfriede Latern, 19 years old, an anti‑aircraft helper who had spent months cranking rangefinders while bombers droned overhead, was captured outside Frankfurt.

She weighed barely 90 pounds. She had not eaten a full meal in 11 days. When the Americans loaded her onto a truck bound for a transit camp, she was too weak to climb the tailgate. A Black American soldier, Technician Fifth Grade Woodrow Pettigrew, lifted her up as gently as if she were his own sister.

“I did not know what to feel,” Elfriede later wrote in a letter to her niece decades after the war. “Gratitude, shame. I had been taught to hate these people, and here one was carrying me.”

The American Machine of Abundance

The women were transported to temporary processing camps—former Wehrmacht barracks, requisitioned schools, fenced compounds in liberated towns. The camps were crowded, chaotic, and smelled of rain‑soaked canvas and disinfectant. But they were not death camps.

They were not starvation camps. They were holding facilities run by an army that had supply lines stretching back across the Atlantic Ocean. And those supply lines carried things the German women had not seen in years: coffee, sugar, flour, powdered eggs, tinned meat, and corn.

Bright golden American corn. The women did not know it yet, but what awaited them at the American field kitchens would challenge everything they had been taught about their captors and about themselves.

The German women had no idea what fed them. They saw only the end result: hot meals served three times a day. Fresh bread. Real coffee, not the bitter acorn substitutes they had choked down for years. Meat that was not horsemeat or mystery rations stamped with codes they could not read.

But behind every meal was a machine so vast, so powerful, that it reshaped modern warfare itself. The United States military supply system in 1945 was the largest logistical operation in human history.

Every day, American forces in Europe consumed 800,000 tons of supplies: food, fuel, ammunition, medicine, clothing. All of it shipped across the Atlantic, unloaded at ports in France and Belgium, then trucked or railed hundreds of miles to the front lines.

By April 1945, the US Army operated more than 240,000 trucks in Europe alone. The famous Red Ball Express, a convoy system that ran day and night, moved 12,500 tons of supplies every 24 hours at its peak. Prisoners of war were fed from the same kitchens as American soldiers.

This was not kindness. It was doctrine. The Geneva Convention required it. But more than that, General Dwight Eisenhower understood something his enemies did not. Well‑fed prisoners did not riot. They did not attempt mass escapes. They did not spread typhus or dysentery through overcrowded camps.

Feeding prisoners was strategic. It was efficient. And it sent a message. Corporal Emmett Lindquist, a Swedish‑American supply clerk from Minnesota, wrote home to his wife in late April 1945.

His letter, preserved in the Minnesota Historical Society archives, described the scene at a transit camp near Koblenz: “We unloaded six truckloads of rations today—canned beef, powdered milk, flour, coffee, sugar, and 200 crates of Iowa corn. The German prisoners stared like we had delivered gold bars. One of their officers asked me if this was food for the guards. I told him, ‘No, it’s for everyone.’ He did not believe me.”

The field kitchens operated like assembly lines. Private First Class Lester Szymanski, a Nebraska farm boy assigned to the Third Armored Division’s mess unit, worked 14‑hour shifts. He and his crew could feed 1,200 men in under two hours.

Breakfast was powdered eggs, toast, coffee, and canned fruit. Lunch was stew or hash. Dinner was meat, potatoes, vegetables, and bread. And the German POWs received the same rations—not smaller portions, not leftovers—the same food cooked in the same pots and served on the same tin trays.

For women like Renate Stahlberg, a military nurse who had spent the final year of the war treating wounded soldiers in hospitals with no morphine, no bandages, and no heat, the abundance was impossible to process. She had watched men die from infected wounds because there was no penicillin.

She had boiled and reused surgical thread until it frayed. She had scrubbed bloodstains from her only uniform in freezing water because there were no replacements. And now, sitting on a bench in an American POW camp, she was handed a metal tray with beef stew, white bread, canned peaches, and coffee with real sugar.

She stared at it. “I thought it was a trick,” she admitted in a 1979 interview with a German documentary crew. “I thought they were showing us this food to humiliate us before taking it away.” But they did not take it away.

Staff Sergeant Virgil Thibodeaux walked the line of seated German women, a ladle in one hand, a cigarette tucked behind his ear. He ladled stew into bowls without comment, his movements practiced and calm. He had done this a thousand times. To him it was routine. To the women, it was a shock.

Hannelore Färber, a communications auxiliary in her early 30s, leaned toward Renate and whispered, “Do their soldiers eat like this every day?” Renate did not answer. She did not know. But the evidence was everywhere.

The American soldiers were tall. Their uniforms fit properly. Their faces were not hollow. Their hands did not shake from hunger. The contrast was undeniable—and it was humiliating.

These were the same soldiers German propaganda had mocked as soft, as weak, as a mongrel nation incapable of discipline or sacrifice. Yet here they stood, well‑fed and well‑supplied, while the so‑called master race sat in muddy camps, starving and defeated.

The abundance itself became a weapon—not bullets or bombs, but butter and bread. The sheer scale of American production overwhelmed the senses. It dismantled certainty. It raised questions the women had been forbidden to ask.

If America could feed its prisoners this well, what did that say about Germany’s claims of superiority? If the enemy was this strong, this organized, this humane, what did that say about the war itself?

Otilie Drexler, an administrative clerk who had once filed reports in a spotless Wehrmacht office in Munich, sat with her tray untouched. She had believed in the Reich. She had believed in the Führer’s promises. She had believed Germany would win.

Now she believed nothing. The food sat before her, steaming in the cool April air, and she understood for the first time that everything she had been told was a lie. What came next would make that realization even sharper.

“Pig Food”

The next evening, the women lined up for dinner as they had the night before. The routine had become familiar: stand in line, take a tray, move past the serving station, sit on the long wooden benches, eat in silence while American soldiers watched from a respectful distance.

But tonight, something was different. As Analise Bräunig reached the front of the line, she froze. On the serving table, piled high on metal trays, were dozens of bright yellow corn cobs. Each one was grilled, charred black in spots, glistening with melted butter. Steam rose from them in the cool evening air.

The smell was sweet, smoky, rich—and Analise had no idea what she was looking at. Behind her, Waltrud Pfeifer leaned forward to see what had caused the delay. When she saw the corn, her face twisted in confusion.

“Was ist das?” she muttered. “What is that?” Private Delbert Martinelli, a cheerful Italian‑American from Brooklyn, grinned and held up a cob. “Corn, fresh off the grill. You’re going to love it.” He dropped two cobs onto Analise’s tray with a pair of tongs.

She stared down at them, bewildered. Waltrud took her tray and moved down the line. When she sat down, she leaned toward Renate Stahlberg and whispered urgently, “They are feeding us Tierfutter. Animal feed.”

The word spread through the group like wildfire. *Tierfutter. Schweinefutter. Viehfutter.* Pig food. Livestock feed. Elfriede Latern looked at the corn on her tray and felt her stomach turn.

She had grown up on a farm outside Dresden. She knew exactly what corn was. Her family had grown it every summer—not to eat, but to chop into silage and feed to the pigs and cattle. Corn was not human food.

It was coarse. It was cheap. It was what you gave to animals when you had nothing better. And now the Americans were serving it to them as a meal.

Hannelore Färber held her cob by the very tip, as if it might contaminate her fingers. She turned it slowly, inspecting the kernels, the char marks, the melted fat dripping onto her tray. “Why are they doing this?” she whispered. “Are they mocking us?”

Otilie Drexler, the former administrative clerk, shook her head slowly. Her voice was bitter. “They think we are animals. That is why.”

The cultural divide was absolute. In Germany, corn had been grown for centuries, but never as a food crop for people. It was called *Mais*, and it was animal fodder.

German farmers planted it, chopped it green, packed it into silos, and fed it to livestock through the winter. No respectable German family would sit down to eat corn. It was unthinkable.

But in the United States, corn was a staple. By 1945, American farmers produced over 3 billion bushels of corn annually. Sweet corn, the kind meant for human consumption, was grilled at summer picnics, boiled at family dinners, served at state fairs and church socials.

It was as American as apple pie. To a boy from Iowa or Nebraska, grilled corn was childhood. It was summer evenings and backyard barbecues. It was normal. To a woman from Berlin or Munich, it was livestock feed.

Private Lester Szymanski, the Nebraska farm boy working the grill, noticed the women were not eating. They sat in rows on the benches, trays in front of them, corn untouched. He walked over to Staff Sergeant Thibodeaux.

“Sarge, they’re not eating the corn.” Thibodeaux glanced over. He saw 34 women staring at their trays like they had been served poison. He chuckled. “They don’t know what it is.”

“Should I explain?” “Won’t help. Show them.” Lester grabbed a cob from the grill, walked to the nearest table, and stood in front of the women. He made eye contact with Analise, smiled broadly, and took an enormous bite.

He chewed slowly, theatrically. Butter ran down his chin. He grinned. “See? It’s good.” The women did not move.

Analise looked at Waltrud. Waltrud looked at Renate. Renate looked at Hannelore. No one wanted to be first. Mechthild Weidmann, a former barracks supervisor in her late 30s, folded her arms across her chest.

“I will not eat pig food.” Elfriede, the youngest, stared at her cob. She was hungry. She had been hungry for months. But the idea of eating animal feed, of lowering herself to that, made her throat tighten.

Across the compound, Corporal Emmett Lindquist watched the scene unfold. He had seen this before with other German POWs—the shock, the refusal, the stubborn pride. He pulled out his notebook and wrote a single line:

> “They think we are feeding them livestock rations. They have no idea this is what we eat at home.”

The corn sat on the trays, cooling in the evening air. The butter began to congeal. The char marks no longer steamed, and still no one took a bite.

The American soldiers exchanged glances. Thibodeaux shrugged. “Leave them be. They’ll eat when they’re hungry enough.” But hunger alone would not be enough to cross this divide. What it would take was something simpler, something human: curiosity.

The First Bite

The evening air grew cooler. Shadows stretched across the camp as the sun dropped behind the tree line. The women sat on rough wooden benches, their metal trays before them, the yellow corn cobs growing cold. Nobody moved to eat.

Analise Bräunig held her tray on her lap. She could feel the warmth fading from the corn. The butter had begun to harden into pale streaks across the kernels. The smoky smell still drifted up to her nose, sweet and unfamiliar.

She was hungry—desperately hungry. For months she had survived on watered‑down soup, stale bread, and whatever scraps she could find. She had eaten turnips so rotten they made her gag. She had chewed on dried peas until her jaw ached.

She had gone days without anything solid in her stomach. And now real food sat in front of her. But it was corn. Animal feed. Pig food.

Around her, the other women whispered in German. Waltrud Pfeifer shook her head in disgust. “I would rather starve.” Mechthild Weidmann pushed her tray away. “This is an insult.”

Otilie Drexler stared at her corn with cold eyes. “They are treating us like livestock.” Only Elfriede Latern said nothing. She was too hungry to speak, too hungry to care about dignity. She stared at the corn like a starving dog staring at a bone.

Across the compound, the American soldiers finished their own meals. They ate the same corn, the same rations, with no hesitation. Private Lester Szymanski gnawed on a cob while laughing at something Private Martinelli said. Staff Sergeant Thibodeaux wiped butter from his chin with the back of his hand.

They were not pretending. They genuinely enjoyed this food. Analise watched them carefully. She thought about the war, about the speeches, about everything she had been told.

Germans were the master race. Americans were primitive, uncultured, inferior. They were mongrels who ate garbage and could not build a civilization. Yet here they were—strong, healthy, well‑fed.

And here she was—starving, defeated, sitting in the mud. Who was inferior? Now the question burned in her mind.

She looked down at the corn again. The kernels gleamed in the fading light. The char marks from the grill made patterns across the surface. It did not look like animal feed. It looked like food. Real food.

Her stomach growled loudly. Waltrud glanced at her. Analise made a decision. She picked up the cob. It was heavier than she expected, slippery with butter.

She brought it to her lips. Then she stopped. What if she was wrong? What if it tasted like cattle feed? What if the others laughed at her?

She thought about her grandmother, who had taught her that corn was not fit for people. She thought about her mother, who would have been horrified to see her daughter eating from a pig trough. But her grandmother was not here. Her mother was not here. Only hunger was here.

Analise closed her eyes and bit down.

The taste exploded across her tongue. Sweetness—rich, natural sweetness unlike anything she had experienced in years. The kernels were tender and juicy, bursting with flavor as she chewed.

The butter added a creamy richness. The char from the grill gave it a smoky depth that made her mouth water for more. Her eyes flew open. This was not pig food. This was delicious.

She took another bite, bigger this time. Then another. She could not stop herself. Waltrud was staring at her.

“What are you doing?” Analise did not answer. She kept eating. Waltrud watched for a long moment. Then slowly, she picked up her own cob.

She sniffed it suspiciously. She touched her tongue to a single kernel. Her eyebrows rose. She took a real bite. Chewed. Swallowed.

“My God,” she whispered. “My God.” Within seconds, others followed. Elfriede grabbed her corn and devoured it like she had not eaten in months. Renate Stahlberg took careful, measured bites, savoring each one.

Hannelore Färber ate with tears running down her cheeks—tears of relief, of exhaustion, of shame. Even Mechthild Weidmann, who had pushed her tray away, quietly pulled it back and began to eat.

Only Otilie Drexler hesitated. She watched the others for a full minute. Then, without expression, she lifted her corn and bit into it. Her face did not change, but she finished both cobs without stopping.

The compound fell quiet except for the sound of chewing. Private Martinelli nudged Lester Szymanski. “Hey, look—they’re eating it.” Lester grinned. “Told you they would.”

Staff Sergeant Thibodeaux lit a cigarette and watched the scene with quiet satisfaction. “Same thing happened with the last group. Germans always think corn is for pigs. Then they taste it.”

He exhaled smoke into the evening air. “Give them an hour. They’ll be asking for seconds.” He was right.

Before the sun fully set, Elfriede walked back to the serving line. She held her empty tray and pointed at the remaining corn. Her eyes asked the question her words could not.

Private Martinelli loaded two more cobs onto her tray. “For the road, sweetheart. There’s plenty.” She nodded gratefully and returned to her seat.

Analise watched her go. She looked down at her own empty tray, her fingers sticky with butter. For the first time in weeks, her stomach was full. For the first time in months, she felt something like hope.

A simple cob of corn had done what no speech, no order, no propaganda could do. It had begun to change her mind about the enemy.

Food as a New Language

The days that followed were different. Something had shifted in the camp. It was not obvious. The barbed wire still stood. The guards still patrolled. The women were still prisoners.

But the tension had eased. Meals became moments of quiet connection. The women no longer approached the serving line with fear or suspicion. They came with empty trays and left with full stomachs. Some even nodded at the American cooks.

A few attempted small words in broken English: “Thank you. Good. More, please.” The Americans responded with smiles and extra portions.

Corporal Emmett Lindquist noticed the change first. He had been stationed at POW camps before, processing captured Wehrmacht soldiers and SS officers. Those men had been sullen, hostile, defiant even in defeat. These women were different.

They were tired. They were broken. But they were not angry. Lindquist wrote in his journal on April 20th, 1945:

> “The German women have stopped treating us like enemies. I do not know when it happened exactly. Maybe it was the corn. Maybe it was the coffee. But something changed. Yesterday, one of them asked me about my family. She wanted to know if I had children. I showed her a photograph of my son. She smiled and said he looked healthy. That was all, but it felt like something important.”

Food became a language both sides could speak. Staff Sergeant Virgil Thibodeaux understood this instinctively. He had grown up in Louisiana, where meals were sacred. His mother had taught him that you could learn more about a person over a bowl of gumbo than through a hundred conversations.

He applied this wisdom to the camp. When new supplies arrived, he made sure the German women saw them being unloaded—crates of vegetables, sacks of flour, tins of meat, bags of real coffee beans. He wanted them to understand that this abundance was not temporary.

It was constant. It was American. One afternoon, Analise Bräunig approached the field kitchen during preparation time. She stood at a respectful distance, watching Private Lester Szymanski work the grill. Lester noticed her and waved her closer.

She hesitated, then walked over. He pointed at the corn lined up beside the grill, then at the fire, then made a rotating gesture with his hand. She understood he was offering to teach her.

For the next hour, Analise learned how to grill corn the American way. Lester showed her how to turn the cob slowly, how to watch for the kernels to blister, how to brush on butter at the right moment. She burned her first cob. Lester laughed and handed her another.

By the third try, she had it right. When she bit into her own creation, she smiled—a real smile, unguarded and genuine. Lester grinned back. “See? Easy.” She did not understand the word, but she understood the meaning.

Similar scenes played out across the camp. Renate Stahlberg, the military nurse, began helping organize meal distribution. Her medical training had taught her efficiency and order. She brought those skills to the serving line, arranging trays, managing portions, keeping things moving smoothly.

Staff Sergeant Thibodeaux was impressed. Within a week, he had given her unofficial authority over the process. Mechthild Weidmann, the former barracks supervisor, took charge of cleanup.

She organized the other women into work groups, assigning tasks, enforcing standards. The American cooks joked that she was stricter than their own officers. Private Martinelli called her “the general” behind her back. She pretended not to hear, but once Lindquist saw her almost smile.

Waltrud Pfeifer discovered that Private Woodrow Pettigrew played the harmonica. One evening after dinner, he sat on an empty crate and played a slow blues melody. The sound drifted across the camp, mournful and beautiful.

Waltrud listened from her bench. When he finished, she clapped softly. Pettigrew looked up, surprised. He nodded at her and played another song. After that, the evening concerts became routine.

Women gathered near the kitchen tent after meals, listening quietly as Pettigrew played. Sometimes the American soldiers joined them. Sometimes everyone just sat in silence, sharing the music. For those few minutes, the war felt far away.

Hannelore Färber later wrote about these evenings in a letter to her daughter, decades after the war ended:

> “There was a Black American soldier who played the harmonica. I did not know his name then. We were not supposed to speak to each other, but every night he played for us—sad songs, beautiful songs. I think he was homesick, just like we were. In those moments, I forgot he was the enemy. I forgot I was a prisoner. We were just people listening to music together.”

The propaganda had said Americans were cruel. The propaganda had said they were uncivilized. The propaganda had said they would show no mercy.

But the evidence was in front of the women every day: hot meals, clean water, medical care, music, humanity. Otilie Drexler, who had once believed every word the Reich told her, sat alone one evening and wrote a single sentence in her notebook:

> “Everything I was taught was wrong.”

She underlined it twice. The corn had been the beginning, but the truth went deeper than food. These women were learning that their enemy was not a monster. Their enemy was human. And that realization would stay with them long after the war ended.

Going Home to a Ruined Country

The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945. Germany surrendered. The guns fell silent. The killing stopped. But for the women in the transit camp near Koblenz, liberation did not come immediately.

They remained prisoners for several more weeks while the Allies sorted through millions of displaced people, refugees, and captured soldiers. During this time, the routines continued. Meals were served. Corn was grilled. Coffee was poured.

The women worked alongside the American cooks, helping where they could, filling the empty hours with useful tasks. Then, in late May, orders came. The women would be transferred to British and French custody for final processing. From there, they would be released to return home.

Home? The word felt strange now. What home? Germany lay in ruins. Cities that had stood for centuries were piles of rubble. Factories were destroyed. Farms were abandoned. Millions of people wandered the roads searching for family members, shelter, food.

The Germany these women had left no longer existed. On the morning of their transfer, the women gathered their few belongings and lined up near the camp gate. American trucks waited to take them to the next processing center.

Staff Sergeant Virgil Thibodeaux stood by the gate, watching them prepare to leave. Analise Bräunig walked past him. She stopped for a moment. They looked at each other.

She did not know enough English to say what she felt. He did not know enough German to respond. But words were not necessary. She nodded. He nodded back. Then she climbed into the truck.

Private Lester Szymanski handed out small packages to the women as they boarded. Each package contained a tin of meat, a chocolate bar, and two cobs of dried corn. “For the road,” he said, grinning.

Most of the women took the packages with quiet thanks. Some clutched them tightly as if holding something precious. Elfriede Latern looked at her package and then at Lester. Her eyes were wet.

“Danke,” she whispered. “Thank you.” He understood that word. “You’re welcome, kid. Take care of yourself.”

The trucks pulled away. The women watched the camp disappear behind them. None of them knew what awaited them in Germany. But all of them carried something with them: memories.

The journey home was long and difficult. The women passed through destroyed cities and burned villages. They saw bodies still lying in the streets. They saw children begging for food. They saw old men digging through rubble with their bare hands.

This was the Germany that Hitler had promised would last a thousand years. It had lasted twelve. When Analise finally reached her hometown near Cologne, she found her family’s apartment building destroyed.

A British bomb had hit it in February. Her mother and younger sister had survived by hiding in the basement. Her father had not. She did not cry. She had no tears left.

But that night, sitting in a temporary shelter with her mother, she told the story of the American camp. She described the food, the abundance, the kindness of the soldiers. And she told her mother about the corn.

“They grilled it over open flames,” she said. “It was sweet and soft, nothing like what we feed to pigs. It was delicious.” Her mother listened in silence.

“I do not understand,” her mother finally said. “Why would they treat prisoners so well?” Analise thought about Corporal Lindquist’s answer: because it was right.

Similar conversations happened across Germany in the months that followed. Women who had been held in American camps told their families what they had experienced. They described the rations, the medical care, the respect they had received.

Many families did not believe them at first. The propaganda had been too strong. The lies had gone too deep. But the women insisted.

“I was there,” Renate Stahlberg told her brother when he questioned her story. “I saw it with my own eyes. I ate their food. I worked in their kitchen. They treated us like human beings.”

Slowly, the truth spread. American occupation forces distributed food aid throughout their zone. They brought in supplies, rebuilt infrastructure, and fed millions of starving Germans through the winter of 1945–46.

The corn kept coming. Germans began to eat it. By the 1950s, sweet corn had become an accepted food in West Germany. Farmers began growing it for human consumption. Supermarkets stocked canned corn from America.

Recipes appeared in German cookbooks. The change was slow, but it was real. In 1987, a German oral history project called *Stimmen der Generation* interviewed elderly women about their wartime experiences. Several of them had been held in American POW camps.

Almost all of them mentioned the corn. Analise Bräunig‑Sauer, now 75 years old, laughed when the interviewer asked about it. “We thought they were mocking us,” she said. “We thought it was animal food. And then we tasted it.”

She paused, her eyes distant. “That was the moment I knew we had been lied to. About everything. If they had lied about something as simple as corn, what else had they lied about?”

She smiled sadly. The answer, of course, was: everything.

A Small Story with a Big Truth

The story of German POW women and American corn is small in the vast history of World War II. It does not appear in most textbooks. It did not change the outcome of any battle.

But it changed minds. It challenged beliefs. It planted seeds of understanding between enemies. Sometimes history turns on grand events—invasions, treaties, the fall of empires.

But sometimes it turns on something smaller: a shared meal, a moment of kindness, a single bite of corn. In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its tanks or its bombers. It was its abundance—and its willingness to share it, even with those who had been taught to hate.

The German women who were captured in 1945 expected cruelty. They received corn. They expected starvation. They received abundance. They expected monsters. They found men—tired, homesick men who shared their food without hesitation.

This was not propaganda. This was reality. And it shattered everything these women believed about their enemy. Decades later, when they told their grandchildren about the war, many of them remembered the same moment: the bright yellow cobs, the melted butter, the shock of sweetness on their tongues.

They had been taught that Americans were primitive. They learned that Americans were generous. They had been taught that corn was for animals. They learned that it was delicious.

And in learning these small truths, they began to unlearn the great lies. Sometimes peace does not begin with treaties or surrenders. Sometimes it begins with something simpler: a shared meal, an open hand, a single bite of corn.

News

“Never Seen Such Men” – Japanese Women Under Occupation COULDN’T Resist Staring at American Soldiers

For years, Japanese women had been told only one thing about the enemy. That American soldiers were merciless. That surrender…

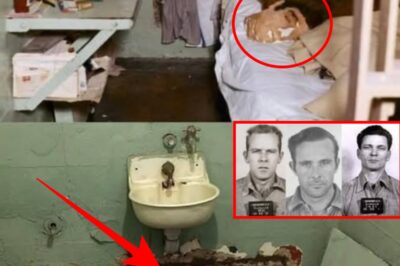

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

End of content

No more pages to load