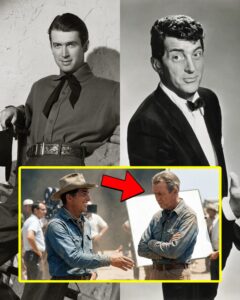

Bandolero set, Texas, 1968. James Stewart stood in the dust watching Dean Martin rehearse a horseback scene. Stewart was sixty, a legend—eighty films, an Oscar, and a western pedigree alongside John Wayne and Gary Cooper. He knew cowboys, real and pretend. And in his opinion, Dean Martin was a singer pretending to be a cowboy.

Stewart turned to director Andrew McLaglen. “This isn’t going to work.” “Why not?” McLaglen asked. “Because singers don’t make cowboys—they make noise.” McLaglen was caught between two stars: Stewart, the veteran authority, and Dean, the box-office draw. Stewart had a point—Dean had never done a grueling western, never ridden for weeks in Texas heat, never proved he could handle the genre’s physical demands.

“This is a mistake,” Stewart repeated, walking to his trailer. What happened over the next three weeks would force him to eat those words—and teach him something about Dean Martin that changed his perspective. Not just about Dean, but about professionalism itself. March 1968: Hollywood was changing, and the old guard—Stewart, Wayne, Fonda—was fading.

Method acting was in. The new generation—Brando, Pacino—worked instinctively, less rigid. Stewart didn’t trust it; he believed in preparation, discipline, punctuality, and knowing your lines. Dean Martin represented everything Stewart didn’t respect: a nightclub singer who “stumbled” into movies, joking through takes, arriving late, leaving early. In Stewart’s view, Dean didn’t take acting seriously.

Bandolero told the story of two outlaw brothers—Stewart and Dean—who rob a bank and take a widow hostage, played by Raquel Welch. It demanded riding, gunfights, stunts—the kind of work that separates pros from pretenders. Stewart agreed because he loved westerns; it was his domain. When he heard Dean was cast as his brother, he almost walked.

Day one: Brackettville, Texas—hot, dusty, brutal. Stewart arrived at 5 a.m., in costume, makeup set, lines memorized. Dean arrived at 7:30, hair perfect, tan perfect, coffee in hand, cracking Vegas jokes. Stewart watched, noting the lateness and casual air. McLaglen called the opening scene—two brothers on horseback escaping a robbery.

They mounted up. Stewart’s movements were precise—decades of riding in films. Dean looked comfortable but newer. First run: Stewart hit every mark. Dean missed one, stopped, apologized, and ran it again—nailed it. Stewart noticed the smile—like this was fun, not serious enough. McLaglen called cut and moved to coverage.

Stewart dismounted and walked past Dean without acknowledgement. Dean noticed but said nothing, that half-smile on his face when someone went cold. The pattern repeated: Stewart early, prepared, serious; Dean later, relaxed, friendly with everyone except Stewart. By day three, the crew noticed—off camera, the two didn’t speak; on camera, they were professionals. The scenes worked; the chemistry held.

Over lunch, Raquel Welch asked Dean, “Is there a problem with Jimmy?” Dean shrugged. “He doesn’t like me.” “Why?” “Because I’m not what he thinks an actor should be.” “What does he think you are?” “A singer who wandered onto a set.” Raquel frowned. “But you’ve made fifty films.” Dean smiled. “Doesn’t matter. He sees what he wants to see.”

“Are you going to prove him wrong?” Raquel asked. Dean exhaled smoke. “I’m just going to do my job.” Week two brought the fight scene—a physical, choreographed sequence with real risk. Stunt coordinator Jack Williams laid it out: Jimmy throws, Dean ducks, body shot, wall slam, charge, roll, finish. “Make it look real—be careful.”

First take: Stewart threw, Dean ducked—perfect timing—came back with the body shot. Stewart sold it, grabbed Dean, slammed him into the wall harder than expected. Dean winced but kept going, charging, rolling, finishing on top. Cut. “One more for safety,” McLaglen said. Dean touched his shoulder briefly, then hid it and reset.

They did another. And another. Four takes—each time, Dean hit the wall, finished the scene, never complained, never asked for pads or a double. That night, Stewart couldn’t sleep, thinking about Dean hitting that wall and just working. He’d known plenty who would demand adjustments after one hit. Dean simply did the job—again and again.

Week three: the canyon sequence—the most dangerous scene in the film. Real horses, narrow rocky passages, high speed. “We have doubles ready,” Jack said. Stewart nodded—he’d do it himself. He expected Dean to use a double. Dean looked at the canyon, studied it, and said, “I’ll do it.”

Jack frowned. “Dean, you don’t have Jimmy’s experience. If something goes wrong—” “I’ll do it,” Dean repeated, calm and certain. They mounted—Stewart on the brown stallion he’d been riding, Dean on a skittish gray mare. “Stay close,” Jack warned. “If anything feels wrong, pull back.” McLaglen called action, and they were off—hooves pounding, walls closing in.

Stewart was in his element—balanced, controlled, natural. Dean kept pace, handling the mare better than expected. Sharp right turn—Stewart leaned and made it. Dean’s horse stumbled on loose rocks—he didn’t panic. He corrected, pulled reins, steadied her, and kept going. Stewart glanced back, saw Dean’s hands—firm, confident, not faking it.

They reached the end. “Cut!” McLaglen called. Stewart dismounted. “You okay?” Dean, breathing hard, nodded. “Yeah, that was intense.” “You handled that stumble well,” Stewart said. Dean shrugged. “The horse did the work. I just held on.” Stewart knew better—at that speed, most riders panic and make it worse. Dean stayed calm and saved them both.

That evening, Stewart found Jack near the trucks. “How much riding experience does Dean have?” Jack looked up. “More than you think.” “Why?” “Curious,” Stewart said. Jack smiled. “He’s been riding since he was a kid—Ohio farms, handling horses. He doesn’t talk about it, but he knows what he’s doing.” Stewart processed it—so Dean wasn’t faking.

“Dean doesn’t fake anything,” Jack added. “He just doesn’t advertise. He prefers being underestimated—makes life easier.” Stewart walked back to his trailer, thinking. Final week: the relationship shifted—subtly. Stewart nodded when Dean arrived, said good morning. Small thaw. Dean noticed but didn’t press. The last major scene was scheduled for Friday.

A campfire—two outlaw brothers talking about their lives, choices, regrets. Dialogue-heavy, emotional, demanding vulnerability. Stewart was comfortable—this was his strength. Dean was nervous—no horse or gun to hide behind. Morning rehearsal: Stewart delivered with quiet, raw truth. Dean listened—really listened—then responded honestly. McLaglen was pleased. “We’ll shoot after lunch.”

Dean stayed on set, pacing, reading lines. “You nervous?” Jack asked. “Yeah,” Dean admitted. “It’s all internal.” “Trust your instincts,” Jack said. “Stewart’s so good at this,” Dean sighed. “I don’t want to disappoint.” “You won’t,” Jack assured him. The fire was lit—real heat, real smoke—adding authenticity. They took positions, the flames between them.

Action. Stewart’s character spoke about their hard childhood—tough father, poverty, the path to outlaw life. His voice was quiet, vulnerable. Dean listened—pain, recognition, empathy flickering across his face—not performed, simply present. Then Dean’s turn—regret, wanting to be better, not knowing how. His voice cracked—unplanned, real.

Stewart heard it and saw it in Dean’s eyes—this wasn’t a performance. This was Dean. McLaglen let it play, never calling cut. When it ended, they stayed still in the moment. Finally: “Cut. That’s it. That’s the one.” The crew was silent; they’d witnessed something rare—two actors truly connecting.

Stewart stood and extended his hand. “That was excellent work.” Dean shook it. “Thank you.” Stewart didn’t let go immediately. “I owe you an apology—for how I treated you and what I thought.” Dean smiled. “It’s okay.” “No,” Stewart insisted. “I judged you before I knew you. I assumed that because you came from music, you weren’t serious. I was wrong.”

Dean was quiet. “I am serious. I just don’t show it the way you do.” Stewart nodded. “I see that now—and I respect it.” They wrapped Bandolero two days later. At the wrap party, Stewart found Dean near the bar. “Can I ask you something?” “Sure,” Dean said. “Why do you do it this way?”

“Do what?” “Act like you don’t care—show up late, joke around—when clearly you care a great deal.” Dean thought, took a sip. “Because if people know you care, they can hurt you. If they think it’s just a job, they can’t touch you.” Stewart studied him. “But it’s not just a job for you.” “No,” Dean said. “It’s everything. I just learned not to show it. People use it against you.”

“So you let me think you were careless,” Stewart said. “And you proved you weren’t.” Dean smiled. “Maybe. Maybe I wanted to see if the great James Stewart could be wrong.” Stewart laughed—first real laugh they shared. “I can be wrong. And I was—about you.” Dean raised his glass to being wrong; Stewart raised his to learning better.

Bandolero premiered in June 1968. Critics praised Stewart and Dean’s chemistry—believable brothers despite differences. Audiences loved it; the film made money. The real success happened off camera, in the Texas dust—when a legend learned that talent doesn’t always look the way you expect, and a singer proved cowboys aren’t born—they’re made by work and commitment.

Years later, in a 1978 interview, Stewart was asked about favorite co-stars. He listed many, then paused. “You know who surprised me? Dean Martin.” “How so?” the interviewer asked. Stewart smiled. “I thought he was just a nightclub act. Turned out he was one of the best professionals I ever worked with. He did his own stunts, never complained, showed up even when hurt.”

“He taught me something important—the way someone arrives doesn’t determine the work they do. Dean would show up late, cracking jokes, and I judged him. But when the cameras rolled, he delivered—solid, honest work. That’s rare.” Dean never knew Stewart said that. Dean died in 1995; Stewart in 1997. Those who worked with both remember tension turning to respect, judgment to admiration.

They remember two men learning there’s more than one way to be great. If this story about earning respect moved you, subscribe and tap the thumbs up. Share it with someone who’s been underestimated. Have you ever proven someone wrong about you? Tell us in the comments—and ring the bell for more untold stories from Dean Martin’s legacy.

News

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but…

U.S Nurse Treated a Japanese POW Woman in 1944 and Never Saw Her Again. 40 Years Later, 4 Officers

The rain hammered against the tin roof of the naval hospital on Saipan like bullets. July 1944. Eleanor Hartwell wiped…

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory on Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

End of content

No more pages to load