-April 6, 1945. Off Okinawa in the East China Sea, dawn breaks over Task Force 58 of the U.S. Fifth Fleet. On radar picket destroyers 16 miles from the main force, sailors scan the horizon, knowing what’s coming. In USS Laffey’s combat information center, operators track not dozens of incoming contacts, but hundreds. Five-inch gun crews load shells marked VT—miniaturized radio transmitters that will revolutionize naval warfare. The goal is desperate: survive Kikusui No. 1, first of ten massive coordinated kamikaze attacks.

At 0600, the sky fills with aircraft. Through the haze comes the drone that will define Okinawa—the sound of hundreds of engines approaching in waves, flown by pilots sealed in cockpits with no intention of returning. Leading the assault are Imperial Japanese Navy special attack units: Zero fighters and Yokosuka D4Y Judy dive bombers carrying 250-kilogram bombs, followed by waves of older airframes pressed into suicide service. Among them, specially trained Ōka pilots sit sealed in rocket-powered flying bombs carried by G4M Bettys.

What happens next will demonstrate the revolutionary impact of American proximity fuses and explain why Japan’s initially devastating kamikaze tactics ultimately failed against the most sophisticated anti-aircraft system ever deployed. The American VT fuse arrived in the Pacific after two years of combat testing, beginning with a single historic shot. Developed via a crash program initiated in 1940 by Section T at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory under Dr. Merle Tuve, the proximity fuse stood alongside radar and the atomic bomb as one of WWII’s three most critical secret projects.

Its principle was brilliantly simple: a miniature radio transmitter-receiver that sent continuous waves and measured their return. When Doppler shift indicated proximity to a target, the fuse detonated automatically. Gunners no longer needed precise range estimates or mechanical timers—the shell knew when to explode. Technical challenges were staggering. Components—including tiny glass vacuum tubes from Sylvania—had to survive 20,000 g acceleration when fired from a five-inch gun, 2,600 feet per second muzzle velocity, and 25,000 rpm spin through rifling.

Everything had to function after violent launch and operate reliably from 100°F to −50°F. By April 1945, American factories had produced more than 15 million naval VT fuses. Manufacturing was distributed across a vast network: Crosley alone made 5,255,913 units—24% of the total—while RCA, Eastman Kodak, General Electric, McQuay-Norris, and 87 firms using 110 factories handled various phases. This industrial surge ensured American forces at Okinawa were equipped with the most advanced anti-aircraft ammunition ever fielded.

The Navy had increased VT allocation from 25% of anti-aircraft ammunition in 1943 to 75% by 1945—recognizing that Pacific combat against kamikazes demanded revolutionary defenses. Every destroyer, cruiser, and battleship carried thousands of VT-fused five-inch shells as primary protection. In stark contrast stood Japan’s kamikaze program, born of desperation. After catastrophic losses in the Marianas and the Philippine Sea, Japan’s experienced pilots and carriers were gone.

Vice Admiral Takijiro Ōnishi proposed special attack units in October 1944, arguing conventional tactics could no longer succeed against overwhelming American firepower. The kamikaze aimed to turn inexperienced pilots into precision-guided weapons. Early math seemed favorable: conventional attacks hit at ~2% against heavily defended ships, while early kamikaze strikes in the Philippines achieved >34%. A Zero with a 250-kilogram bomb could sink or cripple a destroyer—trading one life and one obsolete aircraft for hundreds of casualties and millions in damage.

Training emphasized spiritual preparation over flying skill. Many pilots had <100 hours versus >500 at Pearl Harbor. They learned basic navigation, ship recognition, and the final dive to evade fire, wrote last letters, toasted with sake, and donned headbands or swords. But no ritual could overcome the technology they faced. The Ōka represented the kamikaze concept’s ultimate expression—nicknamed “Baka” by American sailors—a piloted bomb with a 1,200-kilogram warhead, three solid-fuel rockets, and 575 mph terminal speed.

Its fatal weakness was range—barely ten miles—requiring vulnerable Betty bombers to carry it into the teeth of American defenses. The defense contrast was absolute. American ships deployed in concentric rings, with radar picket destroyers bearing the brunt of initial attacks. Each destroyer’s 12–16 five-inch guns fired VT shells, creating overlapping fields of precision fire. A VT shell’s lethal burst radius was ~70 feet versus ~20 feet for time fuses.

More critically, VT eliminated complex range calculations, allowing immediate engagement on detection. April 6 would test these systems to their limits. Kikusui No. 1 involved 391 Navy and 133 Army aircraft—215 Navy and 82 Army kamikazes—297 suicide planes in one coordinated assault. Commander Frederick J. Becton of USS Laffey later described the waves as a swarm of bees heading for the only flower in the desert.

The first wave hit at 0600—radar tracked >50 aircraft from the north. Picket destroyers opened at 12,000 yards with VT shells. The fuses proved devastating—each shell passing within lethal range detonated, filling the sky with fragments. Time fuses turned near-misses into failures; VT turned them into kills. Within minutes, dozens fell into the sea—missions ended miles from targets. But the attacks kept coming.

At 0744, USS Laffey endured concentrated attack—22 aircraft over 80 minutes. Her gunners fired 345 VT rounds, destroying nine attackers. Proximity fuses let crews switch rapidly between targets without fuse-setting delays. Kamikazes dove at wavetop height to avoid radar; VT detonations near the surface created fragment walls that shredded low flyers. Despite devastating fire, Laffey was hit by six kamikazes and four bombs—yet survived—proof of damage control and VT preventing many more reaches.

VT effectiveness wasn’t accidental. Secret combat tests began January 5, 1943, when USS Helena fired the first proximity-fused shells off Guadalcanal. Lieutenant “Red” Cochrane’s aft battery shot down a Val with the second of three salvos—no direct hits—shells detonated on proximity and tore the aircraft apart. That success validated three years of intense development. Each fuse held ~130 components miniaturized into less than a pint bottle, manufactured to thousandths of an inch tolerances.

By Okinawa, analysis showed VT’s mathematical superiority. Time-fused five-inch shells averaged 1,162 rounds per kill; VT reduced this to 310—a nearly fourfold improvement. In optimal cases, results were stunning: destroyer escort USS Abercrombie killed a kamikaze with just two VT rounds in May 1945. USS Morrison, defending on May 4, shot down eight attackers in minutes with VT before being overwhelmed by numbers.

Psychological impact on Japanese pilots was profound. Survivors who aborted reported approaching through walls of exploding shells—black puffs appearing with uncanny accuracy, as if gunners could see their paths. Doctrine assumed high-speed, low-altitude approaches minimized fire; VT invalidated this. Shells that would miss by 50 feet now detonated lethally close—turning final approaches into gauntlets of precisely timed explosions.

Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, directing operations from Kyushu, noted increasingly devastating American defenses. By late April, intelligence estimated fewer than one in four kamikazes reached targets—down from one in three in the Philippines—primarily due to what reports called “new-type” shells that exploded with impossible accuracy. “The enemy’s defensive firepower has increased remarkably,” Ugaki wrote. “Our special attack aircraft are being destroyed at distances we previously considered safe.”

Individual sailors became legends. On USS Hugh W. Hadley, gun crews claimed 17 confirmed kills on May 11 using VT—leading attackers with continuous fire to create walls of detonations. Guns fired ~15 rounds per minute—each with its own electronic brain. Over 52 minutes, Hadley’s batteries destroyed multiple kamikazes in succession, with VT ensuring even shells passing above or below maneuvering aircraft detonated effectively.

USS Aaron Ward on May 3 shows VT’s force multiplier power. When 40 kamikazes attacked, her five-inch batteries fired continuously for 52 minutes—VT shells destroyed six and damaged five severely enough to crash. Commander William Saunders testified that without VT, his ship would have been overwhelmed in ten minutes. Engaging targets without precise rangefinding let guns shift rapidly among threats—impossible with time fuses.

Multiply these accounts across the fleet. In ten Kikusui operations from April 6 to June 22, 1945, Japan launched ~1,900 aircraft in organized kamikaze attacks. U.S. ships, primarily using VT, destroyed hundreds before they could reach targets. Operations research showed ships equipped with VT were three times more likely to survive concentrated attacks than those relying on conventional ammunition. VT turned a catastrophic innovation into a costly but manageable threat.

The disparity in adaptation grew. U.S. forces refined VT tactics—firing patterns that created overlapping fragment spheres—coordinated into VT boxes through which aircraft had to fly. Japanese adjustments—dawn attacks, multi-axis approaches, mixing conventional and suicide aircraft—couldn’t overcome shells that knew when to explode. Production told the industrial story: by June 1945, factories produced ~70,000 VT fuses per day; the war would see >22 million at >$1 billion in 1940s dollars (~$15 billion today).

Crosley employed ~10,000 workers on three shifts, seven days a week. Fuse cost fell from ~$732 in 1942 to ~$18 by 1945. Navy analysis indicated VT prevented the loss of dozens of ships at Okinawa alone. Japanese industry, devastated by bombing and shortages, could produce nothing comparable. Though scientists understood the concept—German reports had filtered in—they lacked precision manufacturing for miniaturized tubes and radar experience to guide development.

Japan’s Type 22 radar operated at wavelengths that made miniaturization impossible given capacity limits. VT’s effectiveness shaped doctrine—by May 1945, pilots were instructed to approach at maximum altitude and dive vertically, hoping to minimize VT exposure. Losses during approach fell, but accuracy collapsed; ships maneuvered out of dive paths, and high-altitude approaches gave radar more time. The adjustment proved counterproductive.

Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner credited VT with making the invasion possible: “Without the VT fuse, our losses from suicide attacks would have been unbearable.” Admiral Marc Mitscher’s flagship USS Bunker Hill survived a devastating May 11 strike partly because VT destroyed three other attackers that would have finished her. Admiral Arleigh Burke recalled in 1978: “All five-inch ammunition was fitted with VT fuses. Those fuses knocked down enemy planes by the dozens. Without them, our losses would have been enormously larger.”

VT’s impact extended beyond stats—it altered the morale equation that made kamikazes viable. Doctrine assumed death would be balanced by near-certain hits. When success fell below 20% due to VT defenses, the exchange became unsustainable. Young pilots—often university students drafted—began to realize their deaths would achieve nothing. Letters recovered after the war show growing awareness that American defenses had evolved beyond commanders’ promises.

Lieutenant Yukio Seki, who led the first official kamikaze unit in October 1944, had devastating success against escort carriers at Leyte when VT comprised only ~25% of AA ammunition. At Okinawa, his successors faced a different reality. Lieutenant Commander Goro Nonaka’s Thunder Gods Corps, equipped with Ōka bombs, lost all 18 Bettys on March 21, 1945, before reaching launch range—radar-guided fighters shot them down—had they broken through, VT walls would have remained.

VT’s sophistication was more than manufacturing—it embodied advances in electronics, materials, and systems integration Japan could not match. Sylvania’s and Raytheon’s miniaturized tubes used special glass formulations to withstand shock. Batteries activated by firing acceleration used stable electrolytes that energized instantly. RF choices minimized interference while maximizing detection range. Every element reflected years of focused research and funding.

Meanwhile, Japanese AA defenses remained primitive. The Type 98 100 mm gun relied on mechanical time fuses set manually. Naval vessels—including Yamato—carried ammunition equivalent to U.S. stocks at Pearl Harbor. On April 7, 1945, Yamato’s 162 AA guns fired thousands of rounds at >300 attacking aircraft—shooting down fewer than ten. Americans lost just ten aircraft while sinking the largest battleship—proof of technological disparity.

VT enabled tactical innovations impossible before. Destroyers developed the “VT umbrella”—firing proximity shells in patterns above friendly ships under attack. Detonations at set distances created protective fragment domes that kamikazes had to penetrate—especially effective against Ōka bombs whose speed made conventional tracking nearly impossible but left them vulnerable to fragment walls.

Throughout Okinawa (April 1–June 22), the Navy expended ~150,000 VT-fused five-inch shells. VT represented ~45% of heavy AA rounds fired yet produced the vast majority of long-range kills; time fuses at ~55% were mostly effective at close range where precision mattered less. Math showed VT was roughly 3–4 times more effective against kamikazes. Human cost differentials were equally stark—ships that exhausted VT and reverted to time fuses suffered sharply higher casualties.

USS Drexler, attacked after expending VT on May 28, was sunk in under a minute by two kamikazes that VT likely would have destroyed—her 158 dead exceeded many destroyers’ entire campaign losses. Even equipped with VT, Admiral Raymond Spruance experienced the threat—his flagship USS Indianapolis was hit in March; he transferred to USS New Mexico, struck in May. “The suicide plane is very effective,” he wrote, “yet VT saved countless ships and lives.”

Strategic implications shaped invasion planning. Japan reserved ~10,000 aircraft for homeland kamikaze attacks; U.S. planners, confident in VT, calculated defenses could meet the threat. Production was set to reach ~100,000 fuses daily by September 1945; new Mk 53/58 fuses with better sensitivity and reliability entered mass production. The invasion fleet would have carried >1 million VT shells—an unprecedented anti-aircraft defense. Atomic bombings ended the war before this test.

But VT’s impact on surrender calculations should not be underestimated. Japanese assessments acknowledged the impossibility of successful defense against invasion fleets protected by “electronic shells.” Admiral Soemu Toyoda testified that calculations showed success rates <10% against VT—making kamikazes militarily worthless. Postwar analysis revealed proximity fuse’s full scope—mobilizing 112 companies beyond primary contractors—creating an industrial ecosystem for the era’s most sophisticated military electronics.

British scientists had conceived proximity fuses in 1940 but lacked resources; they concluded vacuum tubes couldn’t survive gun launch—American engineers proved otherwise. VT’s effectiveness against kamikazes influenced decades of technology—smart munitions, proximity fusing in modern missiles, and CIWS like Phalanx operate on principles pioneered against suicide attacks. Electronic superiority defeating human guidance established a paradigm shaping strategy.

Japanese veterans expressed amazement. Commander Tadashi Nakajima admitted: “The proximity fuse was beyond our imagination. Shells exploded exactly where we flew, as if guided by invisible hands. It destroyed not just our aircraft but the premise that spiritual power could overcome material disadvantage.” Captain Aichiro Goto reflected: “We believed willingness to die guaranteed success. The electronic fuse proved technology could defeat even the most determined sacrifice.”

The contrast reflected fundamentally different philosophies about human life and technology in war. American investment in preserving life through superior technology stood against Japanese willingness to expend life as a weapon. By making kamikaze attacks survivable, the proximity fuse invalidated the cruel logic driving young men to deliberate death. It was not just technological superiority, but a moral statement about how wars should be fought.

VT’s legacy in defeating kamikazes extends beyond military history. The crash program that created it established a model for American technical achievements—from the space program to computing. Collaboration among universities, industry, and the military produced 22 million sophisticated devices under wartime pressure—demonstrating organizational capabilities that defined the postwar era. Johns Hopkins APL remained a technology center—developing guided missiles and satellite navigation.

Dr. Merle Tuve later reflected: “We saved lives by making weapons more effective. Every kamikaze shot down meant sailors who went home to their families. That was worth any amount of effort.” His team’s success validated an American philosophy—applying science to military problems—a doctrine that dominated the Cold War. For Japan, kamikaze failure against VT marked the end of beliefs about spirit triumphing over matter.

Young pilots who died in futile attacks became symbols of leadership’s failure to recognize technology’s reality. Modern Japan’s emphasis on innovation partly traces to 1945’s harsh lessons—electronic fuses defeated human pilots with mechanical precision. VT’s mathematical precision—310 rounds per kill versus 1,162—translated into saved ships, preserved lives, and strategic victory. Each working fuse meant a sailor returned home and a ship lived to fight.

Hundreds of kamikaze aircraft destroyed by VT before reaching targets represented thousands of casualties prevented, dozens of ships saved, and validation of billion-dollar investments in electronic warfare. Technology defeating fatalism reached its climax at Okinawa—radar-guided fighters, VT shells, and damage control systems prevailing against suicide attacks. The pilots—brave young men sacrificed to a lost cause—flew into an electronic killing field their commanders never anticipated.

Their deaths inflicted tactical damage that horrified sailors—but failed to make invasion costs unbearable. The proximity fuse transformed their sacrifice into a manageable threat. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal summarized VT’s contribution: “The proximity fuse has helped blaze the trail to Japan. Without this ingenious protection, our westward push could not have been so swift, and the cost in men and ships would have been immeasurably greater.”

The final accounting was sobering yet decisive. During Okinawa, kamikazes sank 36 American ships and damaged 368—terrible losses, yet far from catastrophic. 4,907 American sailors were killed—a bloody toll, but a fraction of casualties predicted without VT. Japanese losses were absolute—~1,900 aircraft and pilots expended in ten Kikusui operations, plus hundreds more in improvised attacks—achieving tactical results far short of strategic requirements.

Proximity fuses’ victory over kamikazes demonstrated that in modern war, technological superiority can overcome numbers, determination, and even willingness to die. American sailors manning five-inch guns with VT held a decisive edge over pilots on one-way missions. The miniaturized transmitter in each shell nose represented industrial capacity, scientific knowledge, and organizational power no martial spirit could match.

When electronic fuses met human pilots over Okinawa, the outcome was predetermined by factories in Cincinnati, laboratories in Maryland, and America’s belief that technology could preserve life while achieving victory. The math was inescapable: a fuse weighing <5 pounds, with ~130 components, costing $18 by 1945, functioning for <30 seconds, could destroy an aircraft representing years of training, tons of material, and, most tragically, an irreplaceable life.

Multiplied across thousands of engagements, this equation translated into victory through technological superiority. VT’s success validated the American approach to warfare—invest, produce, deploy superior equipment—and proved that quality could overcome quantity of sacrifice. The electronic fuse defeated the divine wind—showing that in modern warfare, advanced technology triumphs over human sacrifice.

News

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

– Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying German prisoners slowed at Camp Ruston as nineteen women pressed their faces against…

When This B-26 Flew Over Japan’s Carrier Deck — Japanese Couldn’t Fire a Single Shot

At 7:10 a.m. on June 4, 1942, First Lieutenant James Muri dropped to 200 feet above the Pacific, watching thirty…

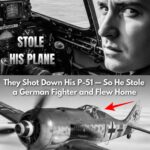

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home

November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

Why British Carriers Terrified Japanese Pilots More Than the Mighty U.S. Fleet

April 6, 1945. A Japanese Zero screams through the morning sky at 400 mph. The pilot, Lieutenant Kenji Yamamoto, has…

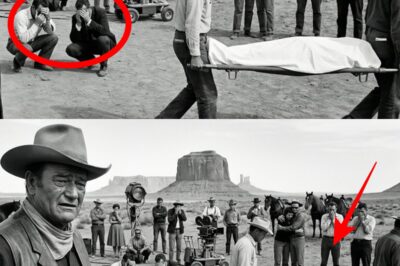

A Stuntman Died on John Wayne’s Set—What the Studio Offered His Widow Was an Insult

October 1966. A stuntman dies on John Wayne’s set. The studio’s offer to his widow is an insult. Wayne hears…

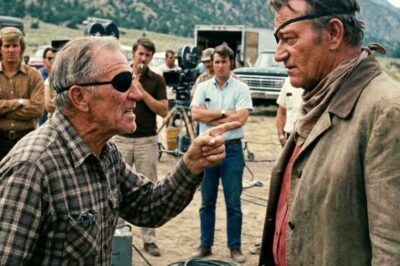

The Day John Wayne Met the Real Rooster Cogburn

March 1969. A one-eyed veteran storms onto John Wayne’s film set—furious, convinced Hollywood is mocking men like him. What happens…

End of content

No more pages to load