She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but back in Hiroshima, she had been Fumiko. The year was 1948, and she was one of thousands of Japanese women who married American soldiers after the war. But unlike the others who shared their stories, Fumiko Nakamura would take hers to the grave.

Her children grew up knowing almost nothing about her life before Iowa. And it wasn’t until they opened a locked box after her funeral that they understood why. This is the story of a woman who survived the atomic bomb, crossed an ocean for love, and spent 70 years hiding the truth from the people she loved most.

Hiroshima, before the flash

August 6th, 1945. Fumiko Nakamura was 19 years old. She woke up that morning in her family’s small wooden house in Hiroshima, just 2 km from the city center. The house had been in the Nakamura family for three generations—modest but comfortable, with sliding paper doors, tatami mat floors, and a small garden where her mother grew vegetables and flowers.

Her father, Kenji Nakamura, was a respected schoolteacher at the local elementary school—a gentle man who spent his evenings writing poetry by candlelight, his brush moving across rice paper with practiced elegance. Her mother, Hana, sold vegetables at the morning market and was known throughout the neighborhood for her kindness and exceptional cooking. Her older brother, Takeshi, 23, worked at the post office and dreamed of becoming a doctor after the war ended, secretly studying medical texts and waiting for the day universities would reopen.

It was a Tuesday morning. The air raid sirens had gone off the night before, wailing through the darkness, but nothing had happened. People were used to false alarms by then. The war had dragged on for so long that fear had become routine, and life continued in its strange wartime rhythm.

Fumiko was supposed to help her mother at the market that day. She had done it every Tuesday and Thursday since she was 12, learning which customers preferred which vegetables, how to arrange displays, how to negotiate prices. But this morning was different.

Her aunt Tomoko, who lived in a village 30 km east, had fallen ill with a high fever. Her mother asked Fumiko to take the early train to check on her and bring medicine from the city pharmacy. Fumiko didn’t want to go. She had plans to meet her best friend Akiko that afternoon to practice calligraphy.

Fumiko loved calligraphy. She had been studying it since she was 7, and her teacher, Master Yamamoto, said she had real talent. He told her she could become a professional instructor someday—one of the few respectable careers available to women. Fumiko dreamed about it constantly.

But her mother insisted. Someone had to check on Aunt Tomoko. Takeshi couldn’t go because of work. Her father had classes to teach. So it had to be Fumiko. She argued briefly, but her mother’s expression made it clear there was no room for negotiation.

So Fumiko packed a small bag with rice balls her mother had made that morning, medicine from the pharmacy, a book of poetry her father had lent her, and her calligraphy supplies in case she had time to practice. At 7:30 a.m., she boarded a train heading east, away from the city.

She found a seat by the window and watched Hiroshima slowly disappear behind her. The morning was beautiful—clear blue sky, warm sun, birds singing in the rice fields. The train was half empty. Most passengers were elderly farmers or merchants. Fumiko opened her book and tried to read, but she couldn’t concentrate. She felt irritated about missing her plans with Akiko.

She had no idea that her irritation had just saved her life.

—

8:15 – The world ends

At 8:15, the world ended.

Fumiko was sitting by the window, watching rice fields pass by, when she saw it—a flash of light so bright it turned the entire sky white. For a split second, she thought the sun had exploded. The light was so intense it hurt her eyes, even through closed eyelids.

Then nothing. Silence.

The shockwave hit. The train shook violently, as if a giant hand had grabbed it and tried to tear it off the tracks. People screamed. Windows shattered inward, sending glass flying through the cabin like a thousand tiny knives.

Fumiko threw herself to the floor and covered her head with her arms. She felt glass cutting her hands and arms. She felt the train tilting. She heard people crying, praying, screaming. No one knew what had happened.

The train screeched to a halt. Fumiko slowly sat up. Her hands were bleeding. Her ears were ringing so loud she could barely hear anything else.

She looked out the broken window and saw something impossible.

A massive cloud was rising into the sky over Hiroshima. It was shaped like a mushroom—black and red and orange and purple—bigger than anything she had ever seen. It was so huge it didn’t look real. The cloud kept growing, rising higher and higher, blotting out the sun.

The other passengers stood now, crowding toward the windows, staring in horror. An old man said it must have been a bomb. A woman whispered that the Americans had finally done it. Another woman began praying loudly.

A man said his wife and children were in that city. His voice broke. He started crying.

Fumiko felt her stomach drop. Her family was in that city. Her mother. Her father. Her brother. Her home. Her friends. Her entire world.

She tried to stand, but her legs wouldn’t work. They felt like water. She tried to speak, but no sound came out.

The train conductor came through, his face pale as paper, his hands shaking. He announced that the tracks ahead were destroyed. They couldn’t go forward or back. Everyone would have to get off and wait.

Wait for what? Fumiko thought. Wait for the world to end?

She didn’t wait. She pushed past the other passengers and jumped off the train. She started running toward Hiroshima. She didn’t care that it was 15 km away. She didn’t care that her hands were bleeding. She had to get home. She had to find her family.

She ran for an hour before her body gave out. She collapsed on the side of the road, gasping for air, her vision blurring, her heart pounding. An old man on a bicycle stopped and asked if she was hurt.

Fumiko told him she had to get to Hiroshima. He looked at her with profound sadness and said no one could get into the city. He said it was gone.

Fumiko screamed that he was lying. He wasn’t.

He helped her onto his bicycle and said he would take her as far as he could. His name was Mr. Sato.

—

The city of ghosts

They rode for three hours. The closer they got to Hiroshima, the worse it became. The air changed. It smelled like burning metal and burning flesh and something chemical.

Ash fell from the sky like snow, covering everything in gray. It got in Fumiko’s mouth, her nose, her eyes. It tasted like death.

People were walking out of the city—or what was left of them. They didn’t look human anymore. Their skin hung off their bodies in strips. Their faces were burned beyond recognition. Their hair was gone. Their clothes were melted into their skin.

Some were naked, their bodies charred black. They walked slowly, mechanically, their arms held out in front of them because it hurt too much to let them hang at their sides. Their eyes were empty, dead. They had seen something no human should ever see.

Fumiko kept asking if anyone had seen the Nakamura family. No one answered. Most couldn’t speak—their mouths too burned. Some tried to make sounds, but only rasping noises came out. They shuffled past her like ghosts.

Some collapsed right there on the road and did not get up. Mr. Sato told her to keep moving. He said if she stopped, she would never start again.

By the time they reached the outskirts of Hiroshima, it was late afternoon. Mr. Sato refused to go farther. He said it wasn’t safe. The fires were still burning. There might be more bombs.

Fumiko thanked him and kept walking. She had to know.

The city was gone—not damaged, not ruined. Gone. Erased.

No standing buildings. No houses, no shops, no temples, no recognizable streets. Just rubble and fire and bodies. Miles of nothing.

Fumiko walked through it in a daze. She tried to find her neighborhood, but she couldn’t recognize anything. Every landmark was gone. The school where her father taught, the market where her mother worked, the post office where Takeshi sorted mail—all of it reduced to piles of broken wood, twisted metal, and ash.

She called out for her parents, for Takeshi. No one answered. The only sounds were the crackling of fires and the moaning of the dying.

She saw a woman sitting in the rubble, holding a child’s body. The child was burned black. The woman rocked back and forth, singing a lullaby.

She saw a man digging through debris with his bare hands, even though his fingers were burned to the bone. He called a name over and over.

She saw an elderly couple lying together in the ruins, holding hands, both dead.

She saw things she would never forget—images that would haunt her dreams for the rest of her life.

—

Three days among the dead

She searched for three days. She slept on the ground, surrounded by corpses. She drank water from broken pipes, not caring if it was contaminated. She ate nothing.

She pulled bodies out of the rubble, hoping and dreading what she might find. But she never found her family—not their bodies, not their belongings, not even a piece of clothing she recognized.

They had simply vanished. Erased. Vaporized. As if they had never existed.

On the third day, Fumiko stopped searching. She sat down in the ruins of what might have been her neighborhood and stared at nothing. She wanted to die. She prayed to die. But her body refused.

She kept breathing—and she hated herself for it.

By the end of August, Fumiko was living in a refugee camp on the edge of the city. Thousands of survivors were packed into makeshift tents and shelters. Most were sick. Something was wrong with them.

Their hair fell out in clumps. Their skin turned black and peeled away. They vomited blood. Strange burns appeared days after the bomb and refused to heal. They bled from their gums, their noses, their eyes.

They died slowly, in agony, while doctors stood by helplessly. There was no medicine, no treatment, no understanding of what was happening. The doctors called it radiation sickness, but they didn’t know how to fight it.

Fumiko watched them die one by one and wondered when it would be her turn. She stopped eating. She stopped speaking. She wanted to die. But her body kept surviving.

—

Serving the men who destroyed her world

In September, American forces arrived. Japan had surrendered. U.S. troops now occupied the ruined nation. They came with trucks full of supplies, with doctors and nurses, with photographers documenting the destruction.

Fumiko hated them. They had done this. They had dropped the bomb. They had killed her family.

But she also needed them. The Americans brought food, medicine, jobs. If she wanted to live, she had to work for the people who had destroyed her life. It felt like a betrayal. But she had no choice. Survival required compromise.

She applied for work in a military base kitchen in Kure, a port city near Hiroshima. She got the job. She scrubbed pots, peeled potatoes, washed dishes, mopped floors—and avoided eye contact with the soldiers.

She didn’t want their pity. She didn’t want their guilt. She just wanted a paycheck so she could eat. The work was hard and the hours long, but it kept her mind occupied.

When she was working, she didn’t have to think. She didn’t have to remember.

That’s where she met Earl Whitlock.

—

The soldier with the notebook

He was a private from Iowa, 23 years old, assigned to the occupation forces in late 1945. He had sandy blond hair, blue eyes, and a face that looked too young for war. He worked in supply logistics, which meant he spent a lot of time in the kitchen.

Fumiko noticed him because he was different from the other soldiers. He didn’t stare at her. He didn’t make crude jokes. He just smiled politely and said “thank you” every time she handed him a tray.

At first, she ignored him. But he kept smiling. Every single day.

“Good morning.”

“Thank you.”

“Have a nice day.”

His Japanese was terrible, but he tried. He carried a small notebook where he wrote down phrases. For some reason, that made her angry. How dare he be kind? How dare he act like everything was normal?

One day in early 1946, Earl brought her a chocolate bar. He set it on the counter and walked away before she could refuse.

Fumiko stared at it for a long time. She hadn’t had chocolate in years. Before the war, her father would sometimes bring home small pieces as a treat. She remembered the taste—sweet and rich.

She didn’t want to take this chocolate. She didn’t want anything from an American soldier. But she was so hungry. So tired. So empty.

So she took it.

She ate it slowly, savoring every bite, and hated herself for enjoying it.

The next day, he brought her another one. This time she said, “Thank you,” in English—one of the few words she knew. He grinned like she’d given him the greatest gift in the world.

After that, it became a routine. He brought her small things—chocolate, canned fruit, a pair of gloves because her hands were cracked and bleeding. Once he brought a book of English phrases with Japanese translations.

He said it might help her. She didn’t understand why he was doing this. She didn’t trust it. But she didn’t stop him. Because his kindness was the only light in her darkness.

—

Choosing to love the enemy

By spring 1946, they were talking regularly. Earl’s Japanese was improving slowly; he practiced every day with his notebook. Fumiko’s English was still almost nonexistent, but she was learning.

He told her about Iowa—about his family’s farm, endless fields of corn and soybeans, how he had never left the state until the war. He showed her photographs: his parents in front of a red barn, his younger sister on a horse, cornfields stretching to the horizon.

To Fumiko, it looked empty and lonely—but also peaceful. No bombs. No fires. No death.

When he asked about Japan, about her family, her life before the bomb, she said there was nothing to tell. He said everyone had a story. She answered that hers ended on August 6th. Everything before that was gone. He didn’t push.

He just sat with her during breaks and talked about nothing important—weather, food, movies.

For the first time since the bomb, Fumiko felt like she could breathe. Like maybe she was still human.

By summer 1946, she realized she was falling in love with him. It terrified her.

She had no right to be happy. Her family was dead. Her city was gone. And here she was, smiling at an American soldier. It felt like a betrayal. But Earl didn’t feel like “the Americans.”

He felt like the only safe thing in a world that had tried to kill her. He was gentle, patient, kind. He made her laugh, which she hadn’t done in over a year. He made her feel human again. That was both a gift and a curse.

One night in July, he asked if she wanted to go for a walk. They went to the harbor and sat on the docks, their legs dangling over the water. The sea was calm. The sky was clear. Stars reflected on the surface like scattered diamonds.

Earl was quiet for a long time. Then, in broken Japanese mixed with English, he told her he wanted to marry her.

Fumiko didn’t understand at first. He repeated it carefully:

“Marry. You and me. Together. Forever.”

She started crying. She said it was impossible. His country had destroyed hers. People would hate them. She had nothing to offer.

He said he wasn’t his country. He was just a man who loved her. He didn’t care what people thought.

For the first time in a year, Fumiko let herself believe that maybe she could have a future. That maybe surviving wasn’t a betrayal.

—

Fighting the rules

Marriage wasn’t simple. In 1946, the U.S. military did not allow soldiers to marry Japanese women. Fraternization was discouraged; marriage was outright banned. Commanders believed Japanese women were trying to trap American soldiers.

Earl didn’t care. He said he would wait. He said he would fight for her. And he did. He wrote letters to his commanding officer. He argued with the chaplain. He researched immigration laws.

Fumiko watched him fight and realized no one had ever fought for her like that. It made her love him even more.

In 1947, everything changed. The U.S. passed the War Brides Act, allowing American servicemen to bring foreign wives to the United States. It was still a bureaucratic nightmare—but now it was possible.

Earl immediately started the paperwork.

Fumiko had to undergo humiliating medical examinations where doctors treated her like livestock. She had to prove she wasn’t a prostitute, signing affidavits. She had to provide documents proving her identity—nearly impossible because all her records had burned in the bomb.

Earl helped her navigate it all. He bribed clerks with cigarettes and whiskey. He called in favors. He refused to give up.

Finally, in November 1947, they were approved.

They married in a small military chapel in Kure on a cold, gray morning. Fumiko wore a borrowed white dress that was too big; she had lost so much weight since the war. There were no family members present—no one from her past remained.

Earl’s army buddies served as witnesses. They clapped and cheered, though Fumiko saw judgment in some of their eyes. It wasn’t the wedding she had imagined as a girl—a traditional Japanese ceremony, beautiful kimono, family all around. That dream had died in the bomb.

This wedding was small and strange and foreign. But it was real. And it was hers.

—

Becoming Frances

In early 1948, Fumiko boarded a military transport ship bound for San Francisco. She was 22 years old. She had lived through the atomic bomb, the occupation, and the slow death of everything she had known. Now she was leaving Japan forever.

The ship was packed with war brides—Japanese, Korean, Filipino—hundreds of women heading to America with husbands they barely knew. Some were excited, chattering nervously about their new lives. Others were terrified, crying quietly in their bunks.

Fumiko felt nothing. She had learned to shut down her emotions to survive. Feeling meant pain. So she stopped feeling.

The voyage took two miserable weeks. The ship rocked constantly. The lower decks reeked of vomit and unwashed bodies. Fumiko was seasick the entire time. She barely ate, barely slept. She just lay in her narrow bunk, staring at the ceiling, wondering if she was making the biggest mistake of her life.

What if America was worse? What if Earl’s family hated her? What if she couldn’t adapt?

When they arrived in San Francisco in March 1948, Fumiko saw America for the first time. Everything was overwhelming. Buildings soared higher than anything in Japan. Streets were wide, clean, and filled with cars—so many cars.

People were loud, confident, moving with a sense of safety she couldn’t understand. Everything was big and bright and alien.

Earl held her hand and told her everything would be okay. She wanted to believe him.

They stayed in San Francisco three days while Earl processed his discharge. He took her to see the Golden Gate Bridge. She stared at it in awe—massive, beautiful, impossible. He bought her an ice cream cone, sweeter than anything she’d had in Japan.

She liked it. But it also made her sad. Her mother would never taste this. Her father would never see this bridge. Every beautiful thing reminded her of what she had lost.

Then they boarded a train east. As America rolled past her window—snow‑capped mountains, endless desert, plains stretching forever—Fumiko felt like she was being swallowed by the landscape.

Earl talked excitedly about Iowa, his family, the farm. Fumiko barely heard him. She was busy memorizing her new identity.

She was Frances now. Frances Whitlock. Not Fumiko Nakamura. That girl had died in Hiroshima.

—

Enemy in a small American town

They arrived in Earl’s hometown in Iowa in late March 1948. It was a farming community called Fairview, population 1,800. Main Street held a post office, general store, diner, church, and grain elevator. Everything else was farms.

Everyone knew everyone—and everyone knew Earl was bringing home a Japanese wife. The reaction was mixed. Some were curious. Most were hostile.

The war had ended less than three years before. Many families in Fairview had lost sons in the Pacific. To them, Fumiko wasn’t a bride. She was the enemy.

Earl’s parents met them at the train station. His mother, Ruth, was a stern woman in her 50s with graying hair pulled into a tight bun. She shook Fumiko’s hand briefly and said “welcome” in a voice that suggested the opposite. Her grip was cold.

His father, Harold, was tall and silent, his skin weathered by years in the fields. He looked Fumiko up and down once and then didn’t look at her again.

They drove to the family farm in silence. Fumiko sat in the back seat, trying not to cry. She could feel their disapproval. This was a mistake.

The farmhouse was small but clean. Ruth showed her to the guest room and said they could stay there until Earl found work. Fumiko thanked her in broken English. Ruth nodded curtly and left.

That night, lying in bed beside Earl, Fumiko realized she’d never felt more alone. Foreign country. Language she barely spoke. No friends. No family.

Earl held her hand and promised it would get better. Fumiko wasn’t sure she believed him.

—

Erasing herself to survive

The first few months were brutal. Fumiko tried desperately to fit in. She smiled at neighbors even when they didn’t smile back. She went to church every Sunday and felt every eye on her.

She learned to cook American food by watching Ruth—pot roast, mashed potatoes, casseroles. Everything tasted bland to her. She missed miso soup. She missed rice. But she cooked what was expected.

Nothing worked. People still stared. Children pointed and whispered.

One day in May, she went to the general store to buy flour. A woman named Mildred Kowalski, whose son had died at Okinawa, saw her and walked out immediately. The store owner, Mr. Patterson, served Fumiko but wouldn’t look her in the eye.

As she left, he quietly suggested she shop at a different time—when fewer people were around.

Fumiko nodded and walked home with her face burning. She cried the entire way. She felt like a leper.

Earl was furious when he found out. He confronted Mr. Patterson. He told Mildred to mind her own business. He even got into a fistfight with a man who called Fumiko a slur. But it didn’t change anything.

The town had decided who Fumiko was. She was the enemy. She would always be unwelcome.

By summer 1948, Earl had steady work at the grain elevator. They moved into a small rental house on the edge of town. It was tiny—two bedrooms, one bathroom, a kitchen with a leaky faucet—but it was theirs.

For the first time since arriving in America, Fumiko had her own space. She cleaned obsessively. She cooked carefully. She listened to the radio to practice English, read children’s books from the library, rehearsed conversations in the mirror.

If she could speak English perfectly, maybe people would accept her.

She also began systematically erasing other parts of herself. She stopped wearing anything that looked Japanese. The few kimonos she had brought—including one her mother had sewn—went into a box at the back of the closet.

She cut her hair short, American‑style. She trained herself to speak louder, to look people in the eye, to smile more.

She erased herself piece by piece. Day by day.

—

Burning the past

One afternoon in late 1948, Earl came home from work and saw smoke in the backyard. Fumiko was standing near a small fire, feeding papers and photographs into the flames one by one.

He stepped closer and realized what she was burning.

Letters from friends who had died in the war. Photographs of her family. A small notebook filled with her calligraphy practice. Her father’s book of poetry.

Everything she had carried from Japan—everything that proved her life before Hiroshima—was going up in smoke.

Earl asked what she was doing. She said she didn’t need them anymore. The past was gone. There was no point holding on. She needed to move forward.

He looked sad but didn’t argue.

That night, lying awake, Fumiko wondered if she had just made a terrible mistake. But it was too late. The letters were ash. Just like Hiroshima.

—

A mother’s decision

In spring 1950, Fumiko discovered she was pregnant. She was terrified. She didn’t know how to be a mother. Her own mother was gone. She had no one to ask.

She was 24 years old and completely alone.

Earl was overjoyed. He painted the spare bedroom pale yellow. He built a crib from scratch. He told everyone in town they were having a baby.

Fumiko wanted to share his excitement. All she felt was fear. What if her child faced the same hatred she did? What if people treated her baby like the enemy?

She made a decision.

Her child would be fully American. No Japanese name. No Japanese language. No Japanese traditions.

Her child would have every advantage she didn’t—even if it meant erasing herself completely.

Dorothy Ruth Whitlock was born on June 14th, 1950. She had Earl’s blue eyes and Fumiko’s dark hair. She was perfect.

Fumiko held her and felt something she hadn’t felt in five years: hope. Maybe this was why she had survived. She promised that Dorothy would never know the kind of pain she had known.

Fumiko would carry that weight alone.

The town’s attitude toward her softened slightly after Dorothy’s birth. People liked babies. They brought casseroles and hand‑me‑down clothes. It wasn’t acceptance. But it was tolerance.

Fumiko threw herself into motherhood. She kept the house spotless. She cooked elaborate meals. She sewed all of Dorothy’s clothes by hand.

She became the perfect American housewife. And with every passing day, Fumiko Nakamura disappeared a little more.

Frances Whitlock took her place.

In fall 1953, their second child was born—a son named Warren Harold Whitlock, after Earl’s father. It was a peace offering. Harold had slowly warmed to Fumiko after Dorothy was born. Naming the boy after him helped.

Warren was different from Dorothy. Quiet. Observant. Even as a baby, he watched everything with dark, serious eyes. Sometimes Fumiko felt he could see straight through her.

—

A life of silence

With two children, Fumiko’s life became a blur of diapers, laundry, cooking, cleaning, school lunches, PTA meetings. She barely had time to think. That was exactly what she wanted. Thinking meant remembering. Remembering meant pain.

She volunteered at school. Joined the church women’s group. Baked pies for every potluck. She became invisible in the best possible way.

By the late 1950s, she had perfected the role. She was Frances now—devoted wife, loving mother. She spoke fluent English, though her accent never fully disappeared. Her pies won ribbons at the county fair. She kept a tidy garden.

But she felt like a ghost—present, but not fully there.

As the children grew, they began to notice things. Dorothy realized her mother never sang. Never seemed truly happy. There was always a quiet sadness in her eyes.

Warren saw how she flinched whenever someone mentioned Hiroshima. How she changed the channel if a war documentary came on. How she never talked about her childhood.

When he was 10, he asked what Japan was like. She said she didn’t remember. He knew she was lying.

—

The generation that didn’t know

In 1965, Dorothy graduated high school. Smart and ambitious, she wanted to go to college. Fumiko had spent years cleaning houses on the side to help save money.

Dorothy enrolled at the University of Iowa to study education. She wanted to be a teacher—just like her grandfather Kenji had been, though she didn’t know it.

The day Dorothy left for college, Fumiko cried. Not just because she would miss her daughter, but because Dorothy was free—free of the past, free of the weight of Hiroshima.

Fumiko had given her that freedom by carrying the burden alone.

Warren graduated in 1971, at 18, terrified of being drafted for Vietnam. Earl suggested college. Warren enrolled at Iowa State to study history, fascinated by World War II.

He devoured books about the Pacific Theater and the atomic bombings. Somehow, he never connected any of it to his mother.

One Thanksgiving, he mentioned a book about Hiroshima survivors. Fumiko went pale. She knocked over her water glass and left the table. She locked herself in the bathroom for an hour.

Warren knew then there was more. But he didn’t know what.

In 1972, Dorothy married Robert Chen, a second‑generation Chinese American. He understood what it meant to be Asian in America. Fumiko watched her daughter marry this confident man and felt a stab of regret.

Maybe hiding the past hadn’t protected her children. Maybe it had robbed them of knowing where they came from.

—

A life half‑lived

In 1975, Earl died suddenly of a heart attack at 53. They had been married 28 years.

Fumiko had loved him. He had saved her. But she had never told him everything.

At the funeral, she didn’t cry. She had run out of tears 30 years earlier.

After Earl’s death, Fumiko became quieter. She stopped going to church. She stopped baking. She spent hours staring out windows. Dorothy visited weekly. Warren called from Chicago, where he taught history.

They tried to get her to open up. She just smiled and said she was fine.

The truth was, Fumiko was exhausted. She had spent three decades pretending to be someone else—burying her language, her name, her family, and her grief. For what? So her children could be American. It had worked. But the cost had been herself.

In the 1980s, she lived alone in the small house. She tended a quiet garden where she secretly grew Japanese vegetables. She watched the news.

In 1989, she saw the Berlin Wall fall. The world celebrated. She felt nothing. History kept moving forward. She remained stuck in 1945.

Dorothy now had two teenage children. Warren had a 10‑year‑old son. Fumiko loved her grandchildren but kept them at arm’s length. She feared their questions.

—

The diagnosis

In early 1989, Fumiko developed a persistent cough. By summer, she was coughing blood. Dorothy insisted she see a doctor.

The diagnosis was lung cancer. Stage 4. Six months, maybe less.

Fumiko received the news calmly. She had always known she was living on borrowed time. She had survived when so many had not.

She told Dorothy and Warren in October. They were devastated. They wanted her to fight. She refused treatment. She said she was tired. She’d lived a full life. She was ready.

Dorothy moved back to Fairview to care for her. Warren visited every weekend. They sat with her, read to her, held her hand. They asked if there was anything she wanted to share.

Fumiko smiled and said no. She told them she loved them. That was all.

In her final weeks, she thought about Chiyo, her younger sister. Chiyo had been 14 in 1945, living in Osaka. After the war, she had searched desperately for Fumiko.

She finally found her in 1950 and wrote a joyful letter, begging for a reply. Fumiko never answered. She couldn’t. Writing back meant opening the door to a past she had worked so hard to bury.

Chiyo wrote anyway—once a month, for 40 years. Letters about her life, her marriage, her children.

Fumiko read every letter. She never wrote back. It was the cruellest thing she ever did.

Dying, she regretted it. But it was too late.

On March 12th, 1990, Fumiko Nakamura Whitlock died at 63. She had lived in America for 42 years. Dorothy held her hand as she went.

Her last words were in Japanese: “Mother, Father, Takeshi… please wait for me.”

The funeral was small. Neighbors came. People from church. They said goodbye to Frances Whitlock.

They didn’t know they were also burying Fumiko Nakamura.

—

The box in the closet

A week later, Dorothy and Warren began sorting her belongings. There were no photographs of Japan. No letters. No souvenirs. It was as if her life had begun in Iowa.

Then Warren found a small wooden box in the back of her closet, wrapped in a faded silk scarf. It was locked. He pried it open with a screwdriver.

Inside were things they had never seen before.

A photograph of a young woman in a beautiful kimono, smiling shyly at the camera. Their mother—but a version of her they had never imagined. Happy. At peace.

Dozens of letters in Japanese, postmarked from Osaka, addressed to “Fumiko.” The return name: Chiyo Nakamura. Dates from 1950 to 1988. Thirty‑eight years of letters.

A notebook filled with elegant calligraphy. A pressed flower. A tiny origami crane.

A military document:

Name: Nakamura, Fumiko

Born: April 2nd, 1926

Place of birth: Hiroshima

And a handwritten list of names:

Nakamura Kenji

Nakamura Hana

Nakamura Takeshi

Next to each, one simple word in English: “Gone.”

Dorothy cried. Warren stared. For the first time, they understood: their mother had not just been “from Japan.” She had been from Hiroshima. She had lost everything. And she had never told them.

She had carried a weight they couldn’t begin to imagine.

—

Finding Chiyo

Warren became obsessed with finding Chiyo. He took leave from teaching, hired a translator, and began writing letters and making calls. It took months. Finally, he found her.

Chiyo Yamada, age 72, living in Hiroshima.

When Warren called, she cried. She said she had thought Fumiko had forgotten her. Warren told her the truth: Fumiko had kept every letter.

Chiyo sent everything—old photographs of Fumiko as a child, letters from 1949, stories about their parents. Dorothy and Warren read every page.

They realized they had never known their mother at all.

In spring 1991, they traveled to Japan. They met Chiyo at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. She was small and frail. When she saw them, she burst into tears and hugged them tightly.

“You look like Fumiko,” she said.

They spent three days together. Chiyo showed them where the Nakamura house had stood—now just part of a park. She took them through the museum. The photographs, the melted glass, the burned clothing—all of it tore at Warren and Dorothy.

Before they left, Chiyo gave them one more letter. It was dated 1949. Fumiko had written it but never sent it.

Warren had it translated.

“Dear Chiyo,

I am alive, but the person I was is gone. America is cold. People hate me. I cannot come back. Everything is gone. I am barely surviving.

So I will stay. I will become American. I will forget Japan. Because if I do not forget, I will die.

I am sorry. I must forget to survive. I cannot be Fumiko anymore.

Please forgive me.

Your sister,

Fumiko.”

Dorothy and Warren wept. Their mother had spent her life trapped between survival and memory, never able to be fully herself.

Before leaving, they took a small portion of their mother’s ashes and scattered them near the cenotaph at Hiroshima, where the names of the dead are inscribed—including the names of Kenji, Hana, and Takeshi.

For the first time, Fumiko came home.

—

The women who erased themselves

Back in America, Warren wrote an article about Japanese war brides. Dorothy founded a small scholarship program in their mother’s name. They told their children the full story.

The story of Fumiko Nakamura is not unique. Between 1947 and 1964, an estimated 50,000 Japanese women married American servicemen and emigrated to the United States.

They faced discrimination. Many hid their pasts. They buried their trauma. They took their secrets to the grave.

These women sacrificed everything. They crossed an ocean for love and paid with their silence. They erased themselves so their children could belong.

Their stories deserve to be remembered.

Because women like Fumiko were not just “war brides.” They were survivors. They were mothers who carried unimaginable loss so their children wouldn’t have to.

And that sacrifice should never be forgotten.

If this story moved you, please subscribe to our channel, hit the like button, and share your thoughts in the comments. History isn’t just battles and dates. It’s untold lives like Fumiko’s.

By sharing them, we make sure they are never forgotten.

News

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid….

“Is This Pig Food?” – German Women POWs Shocked by American Corn… Until One Bite

April 1945, a muddy prison camp near Koblenz, Germany. Thirty‑four German women sat on wooden benches. Their uniforms were torn,…

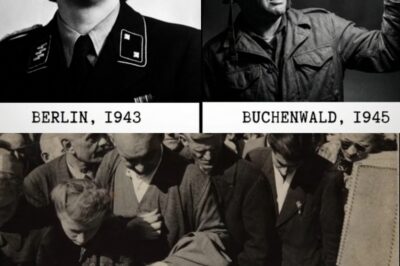

What American Soldiers Found in the Bedroom of the “Witch of Buchenwald”

April 13th, 1945. The outskirts of Weimar, Germany. A beautiful, sunny spring day. A group of American soldiers from the…

German Mechanics Were Shocked When They Saw American Trucks Crossing Mud Without Stopping

August 17th, 1944. The morning mist clings to the abandoned airfield outside Chartres, France. In a makeshift Wehrmacht repair depot,…

End of content

No more pages to load