Much has been said about Katharine Hepburn’s “scandalous” private life, but there’s one lover who sparked more controversy than all the rest. Allegedly, she carried on a romance with married director John Ford. On his deathbed, Hepburn went to visit him, and their conversation was recorded. Left alone, assuming the tape had stopped, Hepburn and Ford continued to talk—and unwittingly revealed a heartbreaking glimpse into their darker history.

Growing up in the early 20th century, Katharine was raised by remarkably progressive parents. Her mother was a member of the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association and often took young Katharine to demonstrations. Their views and actions were considered scandalous by some, but that was only the beginning. As a child, Hepburn despised being a girl, identified more with boys, and chopped off all her hair, insisting everyone call her “Jimmy.”

Instead of persecuting her tomboy nature, her parents celebrated it and encouraged her to be her authentic self. Because of their unconditional support, she blossomed into a woman destined for greatness. She became a talented golfer, but even more importantly, she began to develop a deep love of movies. Hers was a healthy and charming childhood—until an unthinkable tragedy changed everything.

When she was thirteen, Katharine and her older brother Tom went to New York during Easter break to stay with their aunt. The siblings seemed to be the very picture of happiness. But the morning after a trip to the theater, Hepburn discovered something so disturbing it would haunt her for the rest of her life. She found her beloved fifteen-year-old brother dead, seemingly having taken his own life.

Hepburn was inconsolable—but her family’s reaction was chilling. Denial crept through the household like a disease. They refused to admit that Tom had taken his own life and insisted it must have been some kind of botched experiment. Katharine became far more anxious and distrustful of others, and the loss of her brother continued to burden her no matter where she went.

At college, she was awkward and self-conscious, refusing to join the other girls in the dining hall. But her struggle to fit in wouldn’t last forever—after all, Hepburn was a born rebel. College opened up her risk-taking sensibilities. In one of her more notorious moments, she stripped off her clothes and bathed in the Closter pond, and she was even suspended for smoking in her dorm.

In her second year, she joined the drama group and landed the lead in a play that required her to dress as a man—something she often did offstage as well. Around this time she sparked a romance with Ludlow “Luddy” Ogden Smith, a socialite businessman and her future husband. But like many cases of young love, they came together at the wrong time, and fate dealt them a brutal hand.

After getting a taste of theater in college, Hepburn knew in her heart this was her calling. Her father, however, wasn’t convinced—being an actress often went hand in hand with poverty, and he couldn’t imagine she’d find lasting success. Ever strong-willed, Hepburn forged ahead anyway, determined to prove him wrong. It was not going to be easy.

Believe it or not, Katharine Hepburn wasn’t one of those actresses who made a sudden leap to fame. She started in the theater and, at first, stumbled in the most humiliating ways possible. Critics complained about her piercing voice. Then, only a month into her stage career as an understudy, she was called on to fill in for the lead role on opening night.

She completely dropped the ball: she was late, messed up her lines, and even tripped over herself. After being fired, she consoled herself by getting married. But after only a few weeks of playing the wife, she was desperate to run off and get back to her career. Throughout their six years of marriage, Hepburn took full advantage of her husband’s deep devotion to her.

To his credit, Luddy was a doting husband, supporting her emotionally and financially. But his affection was never fully reciprocated. In the end, her heart was made for the theater, not the home. Katharine was also having a hard time holding down a job: no matter how hard she tried, theater companies kept firing her.

In 1931, she asked dramatist Philip Barry why he didn’t want her in his new play. His brutally honest response cut her to the core. But Hepburn was never a fragile little flower. The rejection rocked her, but she kept pushing. That persistence paid off when, just as she seemed ready to flounder, she landed the role that would change her life.

In 1932, she got her big break in *The Warrior’s Husband*, a Broadway show that finally earned her the glowing reviews she craved. And like any proper Hollywood fairy tale, there was a scout in the audience who couldn’t take his eyes off the magnetic lead. In the blink of an eye, Hepburn was at RKO Studios for a screen test.

Landing a role in *A Bill of Divorcement* was the chance of a lifetime, but Katharine Hepburn laid down the law. She wanted \$1,500 a week—a staggering sum for an unknown actress. The studio took a massive risk casting her, but they wouldn’t regret it. Although it was her first screen role, she seemed unfazed by the pressure.

She didn’t wilt—she blossomed. When her debut performance hit the big screen, critics were astonished. On the strength of the film, RKO signed her to a long-term contract. Just two years later, she had won the first of what would become four Oscars—though she never once attended an Academy Awards ceremony. Soon, she discovered that Hollywood life came with its own dramas.

Her move to Hollywood brought her failing marriage to its inevitable end—not only because of her skyrocketing career, but also because of an affair with married agent Leland Hayward. Surprisingly, Hepburn’s divorce ended peacefully, and she and Luddy remained friends for the rest of her life. While she fooled around with Hayward, she also quietly fell for another man.

According to controversial biographer Barbara Leaming, Hepburn also caught the eye of director John Ford while working on *Mary of Scotland* (1936). Ford and Hepburn were like two peas in a pod—there was an ease to their growing friendship. By the time filming wrapped, the director was head over heels for his tomboyish star.

In fact, he was so enamored that he considered divorcing his wife, Mary, to marry Hepburn. Those plans crumbled when Mary threatened to take his daughter away. According to Ford’s niece, Hepburn even tried to sway Mary by offering her \$50,000, hoping to free both Ford and his child. She badly underestimated Mary—and Ford’s demons.

Ford was known as a heavy drinker, though he avoided benders while in production. That’s why Hepburn was shocked when producer Cliff Reid called her in a panic: Ford had gone on a wild binge in the middle of filming. Rushing to his home, she found him alone and completely inebriated.

Trying to “cure” him, she forced him to drink both whiskey and castor oil. To her horror, the concoction made him grievously ill. Hepburn felt sure she’d nearly killed him—and worse still, she realized she couldn’t save him from his own self-destruction. While she waited in vain for her tormented director, her other lover, Leland Hayward, grew increasingly impatient.

After both he and Hepburn secured divorces, it seemed they were finally free to marry. But Hepburn dealt Hayward a heartbreaking blow: she turned down his proposal. Rejecting a powerful man like Hayward was risky, and the consequences were severe. Whether it was because she snubbed his proposal or because of her affair with Ford, Hayward turned his back on her.

He had promised her a part in the stage play *Stage Door*, but after her “betrayal,” he yanked it away. By 1936, Hepburn’s acting career had taken a worrying nosedive. She starred in four consecutive flops, and her prickly personality wasn’t helping. A very private person, she hated interviews, refused autographs, and could be abrasive or downright rude.

This won her few friends in the press, and soon she’d earned a cruel nickname: “Katharine of Arrogance.” Audiences began turning against her as well. The same unconventional qualities that had rocketed her to the top—her boyish style, sharp manner, and lack of traditional glamour—were now drawing harsh criticism.

Aware that her star was fading, Hepburn began to grasp how fickle Hollywood could be. When she learned about the epic production of *Gone With the Wind*, she desperately wanted the lead. But producer David O. Selznick rejected her in the most insulting way possible—saying she wasn’t sensual enough and lacked the character’s sex appeal.

For a time, Hepburn fled Hollywood and its barbed insults, and this escape led her straight into her next major romance. While touring with a theatrical production of *Jane Eyre* in January 1937, she received a dinner invitation from the notorious businessman and aviator Howard Hughes. Introduced earlier through mutual friend Cary Grant, Hughes hadn’t been able to get Hepburn out of his mind.

When she arrived in Boston for a two-week run of the play, Hughes took her on several dates. The two of them made quite the pair—the millionaire flyer and the fiercely independent actress. Hughes wasn’t typical Prince Charming, but something in Hepburn seemed to balance him in a way other women didn’t.

Secretly, however, Hepburn still pined for John Ford and hoped he’d finally leave his wife. When that didn’t happen, she grew tired of waiting. By May 1937, she made a startling decision: she moved in with Howard Hughes. Life with him included yachts, airplanes, attention, and power. But in the end, no amount of money could buy genuine love.

After Hughes set a new record for flying around the world, he accompanied Hepburn on a visit to her family in Fenwick, Connecticut. Midway through the journey, he surprised her with the ultimate question: he wanted to marry her. But Hepburn wasn’t about to surrender her independence so easily. She had one more test in mind.

Her family was one of the most important parts of her life. Before she could marry Hughes, she wanted to see whether he loved what she loved—her family and her hometown. Once they arrived in Fenwick, it became painfully obvious that Hughes detested the entire visit. Worse, Hepburn’s family disliked him as well.

He showed little interest in them, came off arrogant and discourteous, and made no effort to fit in. That was the final straw. Hughes returned to the West Coast without Katharine. Shortly after, things went from bad to worse in her career. After starring in 1938’s *Bringing Up Baby*, Hepburn was publicly labeled “box office poison.”

It was a brutal blow for a struggling actress. She found herself back onstage, touring the country in *The Philadelphia Story*. The play was a huge success—and thanks to her generous ex-boyfriend Howard Hughes, she had the film rights tucked safely away. That would become her secret weapon.

Thanks to her dazzling performance, Hollywood clamored to produce a film version of *The Philadelphia Story*. This time, Hepburn called the shots. First, she sold the rights to the best studio in the business: MGM. But she didn’t stop there. She insisted on playing the lead herself and carefully chose two legendary actors to flank her: Cary Grant and James Stewart.

The movie was tailor-made to restore her reputation. She needed audiences to fall in love with her all over again. It was a masterstroke, and only a sharp-minded actress like Hepburn could have orchestrated such a comeback. When the film hit theaters, her gamble paid off.

*The Philadelphia Story* was a massive success, and Hepburn’s star rose once again. Still, she wasn’t finished proving herself. Fearless and firmly in control, she moved on to a fitting next project: the romantic comedy *Woman of the Year*. Once again, she helped get the project off the ground, gaining considerable power in the process.

She chose her director, George Stevens, and her leading man, Spencer Tracy. Little did she know that meeting Tracy would turn her life upside down. Many believe Spencer Tracy was the love of Katharine Hepburn’s life, and *Woman of the Year* marked the beginning of their long, tumultuous romance.

Hepburn fell for Tracy the moment she laid eyes on him, but at first, he wasn’t equally smitten. Still, their on-screen chemistry was undeniable. Their banter and lingering glances captivated audiences. Studios quickly realized they had struck gold and kept pairing the two together. Behind the scenes, though, their connection was far more complicated.

Their performances were so natural, so loaded with unspoken feeling, that people started to suspect the truth. In order to protect their stars’ morality clauses, studios tried to bury the affair. The silence only fueled rumors. Almost everyone in Hollywood knew what was really going on: Spencer Tracy was a married man, and his long-running affair with Hepburn was scandalous.

Tracy was also a devout Catholic, and his religion weighed heavily on him. When his son was born deaf, Tracy blamed himself, believing it was God’s punishment for his sins. As the years passed, his demons only grew louder—and as his lover, Hepburn was pulled into the storm.

She accepted that Tracy would never divorce his wife for her; his faith simply wouldn’t allow it. Tracy drifted away from his wife and children, spending most of his time in rented rooms and motels. His love for Hepburn could never be openly acknowledged, and the pair were doomed to keep their bond hidden.

Tracy battled anxiety, depression, and addiction. Hepburn herself called him “tortured.” Their relationship deeply affected her career. By the 1940s, she devoted large parts of her time to helping him with his insomnia and drinking. In many ways, she became a maternal figure for him. Yet when asked about motherhood, she freely admitted she’d never wanted children.

For all her self-professed “selfishness,” there was one glaring exception: her unwavering devotion to Spencer Tracy. During the decades they spent together, Hepburn also enjoyed a remarkably enduring career. Unlike many of her contemporaries, she managed to stay relevant as she aged, shifting toward roles that genuinely interested her. In the 1950s, she even took the risk of tackling Shakespeare on film and stage.

The 1960s brought new challenges. Tracy’s health declined rapidly. Hepburn stepped away from acting for five years to care for him. Eventually, they reunited for one last movie: 1967’s *Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner*. The experience was bittersweet. Hepburn would win her second Oscar for the role—but just 17 days after filming wrapped, on June 10, 1967, Spencer Tracy died.

His devoted, secret partner, Katharine Hepburn, was at his side when he passed. Still honoring the secrecy of their relationship, she didn’t attend his funeral. She waited until Tracy’s wife Louise died in 1983 before finally speaking openly about the affair. Yet even this “iconic Hollywood love story” had layers of mystery beneath it.

Throughout her life, Hepburn faced criticism for her boyish looks and fashion sense, not to mention her masculine attitude and disinterest in marriage and children. Rumors circulated that she was a lesbian. Once linked to Spencer Tracy, the whispers expanded to include him as well.

Just as there’s controversy over her alleged relationship with John Ford, there’s fierce debate about her romance with Tracy. Some believe their affair was a cover for their true orientations—that Hepburn was gay and Tracy was closeted. His lifelong struggle with depression is often cited as “evidence” of suppressed desires. Whatever the truth, the speculation can’t erase the genuine, complex bond between them.

Although losing Tracy left a burning void in her life, Hepburn handled her grief in her own unique way. Instead of retreating from the spotlight, she charged toward it. For her performance as Eleanor of Aquitaine in *The Lion in Winter*, she won her third Oscar—though she remained characteristically indifferent to the awards themselves.

She held on to her fame with an iron grip, but as she aged, she evolved. Hepburn had always been guarded with the press, but in later years she opened up more. In 1973, she sat down for a two-hour interview with Dick Cavett, charming audiences with her sharp wit and playful personality. One thing was clear: Katharine Hepburn always knew her own mind.

Her opinionated nature never mellowed. She proudly advocated for birth control and abortion rights, and when asked about politics she didn’t hide behind vague platitudes. In a town where God’s name was frequently invoked, Hepburn had no problem declaring herself a proud atheist. That same year, 1973, she reunited with one of her supposed former flames: John Ford.

Ford’s grandson, who was writing a book about him, arranged a meeting between the two and recorded their conversation. He got far more than he bargained for. At one point he stepped out to his car, mistakenly leaving the tape running. Alone with Ford, Hepburn spoke more freely. At one moment, he told her he loved her, and she reciprocated.

“Take a sense, and I’ll come by in the morning, okay?” he said. “Okay. I love you.” “It’s mutual,” she replied. That private exchange is one of the few concrete pieces of evidence suggesting a deeper history between them than most people suspected. John Ford died in August of that year.

As Hepburn grew older, her contemporaries, friends, and lovers began to pass away one by one. Still, she remained a force. Even into her eighties, she was athletic and energetic, playing tennis almost daily. She took up painting and found new ways to challenge herself. But she wasn’t done revealing secrets.

After her brother’s death, her grief drove her to do something unexpected: she changed her birthdate to his, making herself two years older on paper. The queen of secrets kept that lie alive for decades. Only when she published her autobiography did she confess her real birthday.

In the spring of 1993, Hepburn’s health finally faltered. Up until then, she’d continued to act, but after being hospitalized for exhaustion, her decline began in earnest. Three years later, she battled a severe case of pneumonia, and by 1997, the outlook was grim. She held on for six more years, though they were difficult ones marked by dementia and frailty.

In 2003, Katharine Hepburn died of cardiac arrest at the age of 96. There was, however, one small blessing: she passed away at the place she loved most—her family home in Fenwick, Connecticut.

If you enjoyed this story, please give it a like and subscribe for more.

News

The US Army’s Tanks Were Dying Without Fuel — So a Mechanic Built a Lifeline Truck

In the chaotic symphony of war, there is one sound that terrifies a tanker more than the whistle of an…

The US Army Couldn’t Detect the Mines — So a Mechanic Turned a Jeep into a Mine Finder

It didn’t start with a roar. It wasn’t the grinding screech of Tiger tank treads. And it wasn’t the terrifying…

Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her : “He Took a Bullet for Me!”

August 21st, 1945. A dirt track carved through the dense jungle of Luzon, Philippines. The war is over. The emperor…

The US Army Had No Locomotives in the Pacific in 1944 — So They Built The Railway Jeep

Picture this. It is 1944. You are deep in the steaming, suffocating jungles of Burma. The air is so thick…

Disabled German POWs Couldn’t Believe How Americans Treated Them

Fort Sam Houston, Texas. August 1943. The hospital train arrived at dawn, brakes screaming against steel, steam rising from the…

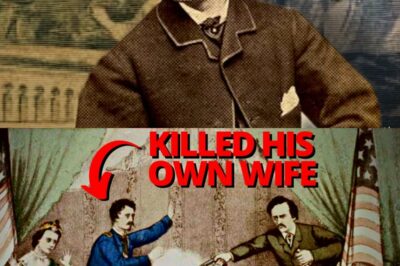

The Man Who Tried To Save Abraham Lincoln Killed His Own Wife

April 14th, 1865. The story begins with an invitation from President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary to attend a…

End of content

No more pages to load