Mae West was a force of nature—a woman who could light up the screen with a glance and scandalize a nation with a single line. But Hollywood’s Golden Age wasn’t ready for her boldness. As her films broke box office records, Mae broke the unspoken rules of what a woman could say, do, or be on screen. The censors fought back—rewriting her scripts, cutting her lines, jailing her, and eventually blacklisting her films. The very industry she saved turned against her, desperate to bury the woman they once couldn’t stop praising. This is the story of how Hollywood silenced Mae West—a tale of power, rebellion, and the cost of speaking out in an era that demanded silence.

If you like stories like this, please consider joining the channel. We post new content every week and would love to have you in our growing community. Now, let’s get into this week’s story: how Hollywood censored Mae West.

She entered the world on a sweltering August day in 1893, though she’d later shave a few years off that date—Mae West was always the author of her own legend. Born Mary Jane West in Brooklyn, it was a name that barely grazed her lips. She would be no ordinary Mary. Mae, as the world would know her, was destined to burn brighter, laugh louder, and rewrite the rules of womanhood in bold red lipstick.

Her father, John, was a boxer turned detective—an Irish‑American brawler who knew New York’s underbelly intimately. Mae absorbed his street smarts like sunlight on a sultry summer’s day. Her mother, Matilda, was the soft‑spoken counterpoint—a Bavarian immigrant with a corseted figure and a mind unbound by Victorian prudery. From her, Mae learned to move with grace, sing with abandon, and never fear the sway of her own hips. Their marriage was a battlefield, but Mae stood at the crossroads of their two worlds: her father’s grit and her mother’s sensuality. The union left her skeptical of love’s promises, wary of forever. Why be chained to one man when the whole world could be your stage?

At five years old, she found that stage—the Royal Theater—and the spotlight beckoned like the North Star. Draped in pink and green satin, she claimed first prize in a talent competition. Years later, she confessed, “I ached for it—the spotlight. It felt like the strongest man’s arms around me.” By seven, she was tap dancing and singing at the Elks Club—a slip of a girl with a swagger entirely her own. Schoolbooks soon gave way to stage scripts. As an adolescent, she took juvenile roles in dusty melodramas, delivering heartbreak and heroics to enthralled Brooklyn audiences.

But Mae wanted more—always more. She carved a niche as “Baby Mae,” playing a moonshiner’s daughter who stormed saloon doors, head held high, in search of her drunken father. From eight to eleven, she stomped across the footlights with all the fire of a woman twice her size. Vaudeville became her proving ground, burlesque her playground. In those burlesque halls, Mae West truly came alive. In her early teens, she danced nude, covered only with a fan as wide as her ambitions, her body dusted in shimmering powder that caught the lights and cast her in a glow of her own making. As the powder fell like glittering snow onto the enraptured front row, Mae proved she understood spectacle like no one else. She was the tease and the punchline—the woman who could make a room erupt with laughter with a single glance or silence it entirely with the curve of a smile.

Mae West was just 18 when she stepped onto the Broadway stage for the first time. The revue flickered briefly, but Mae left an impression that refused to fade. The New York Times singled her out as “a girl named Mae West, hitherto unknown,” praising her snappy way of singing and dancing—a quiet prophecy for the roar she would later unleash. In 1911, she added a husband, Frank Wallace, to her act—a fleeting role in her life that lasted about as long as their double ragtime routine. Their marriage became little more than a legal technicality, with divorce papers lingering unsigned until 1942. In 1935, Wallace tried to revive his career by billing himself as “Mae West’s husband”—an ill‑fated performance quickly forgotten, while Mae kept forging her legend.

Her breakthrough came in 1918 with the Broadway revue “Sometime,” where Mae stole the show with the shimmy—a provocative dance she unapologetically borrowed from African‑American club dancers. Her movements were sultry, her voice a growl of blues, and her rhythm steeped in the influence of performers like Bert Williams. She later took the stage with Duke Ellington’s band in “Belle of the Nineties,” blending her voice with their swing so seamlessly it felt like a jazz romance.

By the early 1920s, Mae had perfected her signature style. Critics sneered that she was the “rough hand‑on‑hip” character, but audiences couldn’t get enough. Mae owned every stage she graced, walking as though the floor tilted in her favor and delivering lines that cut with wit and charm. Her transition to the nightclub circuit paired her with a then‑unknown Harry Richmond on piano, but even as she dazzled cabaret audiences, Mae felt restless. The scripts offered were dull, the roles uninspired. Her mother’s words echoed: you can write your own play. So she did.

In 1926, Mae West’s “Sex” debuted at Daly’s Theater in Manhattan, and it was everything the title promised. Mae starred as a sex worker who proved herself better than the so‑called respectable hypocrites around her. The play crackled with scandal—burglary, spiked drinks, crooked cops, bribery—all wrapped in Mae’s audacious charm. City newspapers refused ads. Variety called it “the nastiest thing ever done on the New York stage.” But Mae, ever the provocateur, understood scandal. The more society tried to suppress it, the more audiences clamored for tickets. “Sex” played to packed houses for over 300 performances, raking in $10,000 a week long after opening night.

Success had its price. The Society for the Suppression of Vice had Mae arrested, charging her with corrupting the morals of youth. The trial turned into a spectacle, and Mae made it a masterpiece of publicity. Sentenced to 10 days in jail, she served eight and emerged a living legend. Silk underwear, she quipped, had been her only concession to her cell’s drab confines. She even wrote to the warden afterward with an unforgettable line: “I hope Warden Duffy will continue making bad men good while I continue making good men bad.”

Mae West didn’t just flirt with controversy—she courted it. Her second play, “The Drag,” was a daring exploration of queer characters and New York’s underground drag balls—decades before “Paris Is Burning” captured their legacy. Soon she caught the disapproving eye of a formidable nemesis: William Randolph Hearst. The media mogul published an editorial calling for censorship to prevent “such sex perversion for dirty dollars.” The backlash was swift: no theater in New York would dare book the production. Undeterred, Mae pressed forward. Her next play, “Pleasure Man,” tackled similar themes and met an equally dramatic fate. After just one Broadway performance, police stormed in and shut it down. Mae, ready for the spotlight even when it was aimed by law enforcement, was arrested yet again. At trial, the jury deadlocked, and Mae strolled out triumphant.

It was her fourth play, “Diamond Lil,” that cemented Mae West’s status as an icon. The story of a diamond‑draped, wise‑cracking hostess in the seedy Bowery of the 1890s, it debuted in Brooklyn in 1928 and sparkled like the gems she adored. By then, her personal diamond collection rivaled royalty—though she famously pawned it all to finance the production. “I had never before seen a human being place a 100% bet on himself,” remarked one acquaintance, summing up Mae’s audacity. The gamble paid off. The play was a runaway success, transferring to Broadway, touring nationally, and defining her persona for decades. Always multitasking, she penned her first novel, “The Constant Sinner,” delving into interracial love, while juggling affairs with lawyers, co‑stars, and dancers. In her autobiography, Mae cheekily confessed, “One Saturday it was 22 times. I was sort of tired.” Among her lovers was George Raft—a future gangster star who, in the late 1920s, was a dancer with real‑life mobster connections. Their fiery fling cooled into lifelong friendship.

Even Mae’s triumphs couldn’t escape the twin shadows of the Great Depression and censorship. The Hays Code—a moralistic chokehold on creativity—banned her plays from film adaptation, leaving her short on cash and opportunities. George Raft threw her a lifeline, recommending her to Paramount Pictures. Paramount was teetering on financial ruin, and Mae’s arrival in Los Angeles made barely a ripple. Gossip columnist Luella Parsons dismissed her as “fat, fair, and I don’t know how near forty.” Mae had no intention of fading. After reading her scripted scenes for “Night After Night,” she rewrote them. When a hatcheck girl said, “Goodness, what beautiful diamonds,” Mae shot back, “Goodness had nothing to do with it.”

Audiences loved her. Paramount, desperate for a hit, made her the star of her own film—using the “Diamond Lil” character but dodging the Hays Code. Lil’s brothel became a dance hall; her name changed to Lou; the title became “She Done Him Wrong.” The studio even let Mae choose her leading man, a rare privilege. She spotted a dashing young man on the street and declared, “If he can talk, I’ll take him.” The unknown actor was Cary Grant. “She Done Him Wrong” catapulted him into stardom. At just 66 minutes, it remains the shortest film ever nominated for Best Picture—its impact anything but small. Lady Lou, draped in diamonds and confidence, turned seduction into an art. When she invited Grant’s character to her apartment, she delivered a line that echoed for decades: “You know, I always did like a man in a uniform—and that one fits you grand. Why don’t you come up sometime and see me?” Mae flipped the script. She wasn’t just luring men; she was setting the terms.

“She Done Him Wrong” also revealed her depth. Lady Lou wasn’t just a temptress; she was sisterly to women in need. To a young girl seduced and abandoned, she offered comfort with a knowing quip: “Listen—when women go wrong, men go right after them.” Her scenes with her Black maid, Pearl (Louise Beavers), offered humor and camaraderie, reflecting the racial dynamics of the era. Mae capped the film with a sultry rendition of Shelton Brooks’s “I Wonder Where My Easy Rider’s Gone”—a daringly bawdy number that cemented her reputation as a trailblazer. Unlike many white performers of her time, Mae openly credited African‑American music and performance as foundational to her style, earning respect even as she pushed boundaries.

“She Done Him Wrong” was a colossal success, grossing an estimated $10 million in the depths of the Depression. Producer William LeBaron later credited Mae with saving Paramount. She wasn’t done. Later that year, she followed with “I’m No Angel,” another smash hitting childhood dream notes: she tamed lions in stilettos, wielded a whip, and tamed every man who crossed her path—including Cary Grant’s character. The climax wasn’t a trial of Mae, but a trial by Mae. Facing a breach‑of‑promise suit, she cross‑examined herself with sharp wit and clever quips, dismantling the case, winning the court, and reclaiming her love. “It’s not the men in your life that counts—it’s the life in your men” became an instant classic.

Mae had now starred in—and helped create—two of the year’s biggest blockbusters. She wasn’t just the face of the new woman; she was writing the scripts, crafting characters, shaping her persona. This level of control made her a target, and a campaign built against her.

The backlash peaked during “Belle of the Nineties” (1934). Religious groups ramped up efforts to combat what they saw as moral decay, forming the Legion of Decency and urging parishioners to pledge against “debauching motion pictures.” The coalition pressured Hollywood to enforce the Production Code, largely ignored since 1930. In 1934, Joseph Breen was appointed to enforce the Hays Code with full authority. A strict moralist, Breen took an uncompromising approach. For years, filmmakers had included sex, violence, and innuendo knowing censors would trim content. Breen had no interest in compromise; his focus was enforcing morality, regardless of box office impact.

This wave of censorship partly reacted to “I’m No Angel.” Religious leaders pointed to its bawdy humor, Mae’s unapologetic sensuality, and cheeky wit as evidence of moral decline. With Breen now at the helm, Mae found herself in the crosshairs. One of his first actions was identifying pre‑Code films that would no longer be permitted. These were withdrawn and effectively banned. “She Done Him Wrong” and “I’m No Angel”—Mae’s two hits—were blacklisted.

As Mae began work on her third film, “It Ain’t No Sin,” the title alone raised red flags. To comply, it became “Belle of the Nineties.” Despite the change, heavy edits remained. Even so, the film showcased her star power: Leo McCarey shot stunning close‑ups, paired her with Duke Ellington’s Orchestra, and delivered a dazzling tableau finale—Mae posed like a living Statue of Liberty. Photoplay called it “a triumph of Mae over matter.” Critics admired her tenacity; audiences were less enthusiastic. The film lacked the unfiltered wit and edge of her earlier work. The formula faltered under censorship.

Mae’s next film, “Goin’ to Town” (1935), still delivered classic May‑isms despite Breen’s eye. To a persistent suitor: “We’re intellectual opposites. I’m intellectual—and you’re opposite.” And, “For a long time I was ashamed of the way I lived.” “You mean you’ve reformed?” “No—I got over being ashamed.” Despite flashes of brilliance, audiences didn’t react like before. Paramount tried a new direction: Mae played a kept woman who stabs her lover and escapes to Alaska, switching identities with missionaries and devoting herself to charity. While the Hays Commission approved, she now faced a more powerful adversary: William Randolph Hearst. His newspapers flooded pages with negative coverage and refused ads. Reasons remain speculative—perhaps a wisecrack about his mistress, Marion Davies; perhaps frustration with censors after heavy edits to “Ceiling Zero.” Mae had her own theory: “I think Hurst didn’t like me because I was a woman making almost as much money as he was. He said he didn’t like my morals—but there he was, a married man with a mistress. Who was he to throw words at me when he lived in a glass house?”

Under mounting pressure, Paramount ended its relationship with Mae. She signed with independent producer Emanuel Cohen, distributing through Paramount. Cohen backed two projects: “Go West, Young Man” (1936), a satire about a sexually voracious actress, was stripped of sharp satire after negotiations with Breen. Mae struggled with writer’s block navigating the censors. Her next film, “Every Day’s a Holiday” (1937), recycled earlier elements, but many signature lines were cut. Audiences and critics tired of the muted formula. It became her first financial failure. Cohen severed ties.

Undeterred, Mae returned to New York and mounted live shows. During her tour—a triumphant return—the infamous “Box Office Poison” ad debuted in The Hollywood Reporter, naming Mae alongside K. Francis, Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, and Fred Astaire. The claim was blunt: these stars had become liabilities. The ad urged studios to drop high‑salaried actors and focus on rising stars like Shirley Temple, Carole Lombard, and Cary Grant—Mae’s discovery. It marked a turning point: Hollywood prioritized youth over seasoned icons. Some, like Crawford and Dietrich, reinvented themselves. Mae’s career never fully recovered. Her major stardom had ended, though her influence remained.

Mae continued working, maintaining a carefully curated public image. She spent over 30 years with Paul Novak—her bodyguard and devoted companion. Despite her hedonistic reputation, Mae lived disciplined: organic diet, regular exercise, writing taken seriously. Far from a lazy diva caricature, she orchestrated every aspect of her performances with precision and artistry. She returned to theatrical roots with “Catherine Was Great,” a bawdy stage play she toured for years—as the only female actor in the cast, commanding the spotlight as the notorious Russian Empress.

In later years, Mae turned to the mystical—mediums, ESP, astrology—adding another layer to her persona. After more than two decades away from the screen, she made a comeback at 77 in the controversial film “Myra Breckinridge.” Polarizing and widely panned, it nonetheless brought a touch of old Hollywood glamour. She clashed with Raquel Welch, but her wit stayed sharp. At 85, she made her final film appearance in “Sextette,” a musical comedy based on one of her stage plays. Though not a critical success, it allowed one last unforgettable line: “Is that a gun in your pocket—or are you just glad to see me?”

Mae’s legacy extended beyond the silver screen. Salvador Dalí immortalized her in surrealist art with the famous Mae West sofa, inspired by her iconic lips. She appeared on the cover of The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” Asked for permission, Mae agreed—but not without her signature humor: “What would I be doing in a lonely hearts club?”

Mae West passed away in her Hollywood home on November 22, 1980, at 88. Her companion Paul Novak opted for an open casket, explaining, “My gal still looked great.”

Thank you for watching this week’s video on Mae West. We’d love to hear your thoughts: Was Hollywood right to censor her? Are there lines that shouldn’t be crossed, or was Mae simply ahead of her time? How do you think she’s remembered today? Let us know in the comments. If you enjoyed this video, please like, share, and subscribe. We post new content every week about amazing women throughout history—tell us who you’d like to see featured next.

A heartfelt thank you to our incredible patrons: Velocity Girl, Zenlifee68, Jillian Barker, Juny Moon, Philip Ggos, Kingsley Clark, Kfum Chung, Harry Thurston, Karen Craig, Michelle Lyneil, Bobby Andrea, Tracy Walsh, Elizabeth CTSB America, Marie Joy Maguire, Amber Perry, Amanda Lynn, Snowball, The Inappropriate Heir, Kendra McN, Maryann Nelson, Deborah Shepard, Ida Claer Jensen, and Kay Fine. Your support breathes life into this project and makes these stories possible. And to everyone watching until the end—thank you for helping this project grow. Stay curious, keep exploring history, and as always, thanks for watching.

News

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

– Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying German prisoners slowed at Camp Ruston as nineteen women pressed their faces against…

Japanese Kamikaze Pilots Were Shocked by America’s Proximity Fuzes

-April 6, 1945. Off Okinawa in the East China Sea, dawn breaks over Task Force 58 of the U.S. Fifth…

When This B-26 Flew Over Japan’s Carrier Deck — Japanese Couldn’t Fire a Single Shot

At 7:10 a.m. on June 4, 1942, First Lieutenant James Muri dropped to 200 feet above the Pacific, watching thirty…

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home

November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

Why British Carriers Terrified Japanese Pilots More Than the Mighty U.S. Fleet

April 6, 1945. A Japanese Zero screams through the morning sky at 400 mph. The pilot, Lieutenant Kenji Yamamoto, has…

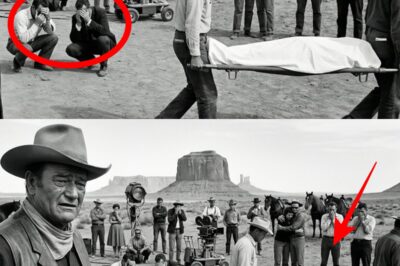

A Stuntman Died on John Wayne’s Set—What the Studio Offered His Widow Was an Insult

October 1966. A stuntman dies on John Wayne’s set. The studio’s offer to his widow is an insult. Wayne hears…

End of content

No more pages to load