Nick didn’t suddenly “develop” schizophrenia—by all accounts, he has lived with it for years. That diagnosis is going to be central to understanding what happened. It also exposes how the mental health system often fails people with serious, chronic illness.

In many cases, schizophrenia and substance use become tangled together. People often self-medicate to quiet symptoms or regain a sense of control. For Nick, that reportedly meant cycles of heroin, cocaine, stimulants, and other drugs. The addiction becomes visible, while the underlying illness stays hidden in plain sight.

Here’s where the system breaks down: once someone is labeled an addict, treatment frequently focuses almost exclusively on sobriety. Nick reportedly went through 18 rehab facilities, many of which treated the drug dependence but did not adequately address the schizophrenia. So the person gets clean, leaves, and returns to the same untreated symptoms. That’s the revolving door—detox, discharge, relapse, repeat.

Even when schizophrenia is treated, another problem often appears. Medications can create serious side effects, and those side effects can be misread as “worsening illness” rather than drug-related reactions. A clinician may see new agitation, blunted emotion, or instability and assume it’s the disorder progressing. Then prescriptions change, dosages shift, and the cycle snowballs.

That snowball effect is devastating because it prevents true stabilization. Instead of carefully separating illness symptoms from medication effects, the system can lump everything together. The person ends up under-treated, over-medicated, or both—without a consistent long-term plan. And without that foundation, relapse becomes more likely because self-medication feels like the only immediate relief.

On top of that, the rehab industry itself can be deeply uneven. I interviewed a psychiatrist who said there are roughly 400 rehab centers in Los Angeles, yet he refers patients to only four. That’s about 1%—and he was blunt about why. In his view, many facilities are not built to handle complex mental illness alongside addiction.

A major red flag is the rise of ultra-expensive “luxury rehab” models. Places charging $70,000 a month often market amenities—pools, scenic retreats, comfort, and curated experiences. Many mental health professionals argue that those perks don’t improve outcomes, and may even undermine treatment. Rehab isn’t meant to be a vacation; it’s meant to be stabilization through difficult, structured work.

Several experts we spoke with also challenged the idea of a quick fix. For severe mental illness, “30 days” is rarely enough to establish lasting stability. It can take months to find the right medication, dosage, and supports—and even longer to rebuild functioning. Treating this like a short-term reset can set people up to fail.

So when you add it all up, a pattern emerges. You have a long-standing schizophrenia diagnosis, widespread self-medication, repeated rehab admissions focused on addiction, and inconsistent treatment of the underlying illness. You also have medication side effects that can be mistaken for the disease itself, driving further instability. And you have an industry where some high-priced centers may do more harm than good.

Against that backdrop, it’s not surprising what many believe will be the core legal strategy. Based on what we’re hearing, Nick’s defense is likely to pursue **not guilty by reason of insanity**. There are also multiple witnesses who could testify to this long-term cycle in a way that resonates with a jury.

News

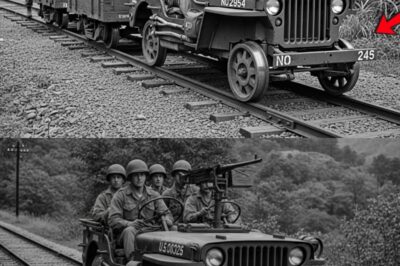

The US Army’s Tanks Were Dying Without Fuel — So a Mechanic Built a Lifeline Truck

In the chaotic symphony of war, there is one sound that terrifies a tanker more than the whistle of an…

The US Army Couldn’t Detect the Mines — So a Mechanic Turned a Jeep into a Mine Finder

It didn’t start with a roar. It wasn’t the grinding screech of Tiger tank treads. And it wasn’t the terrifying…

Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her : “He Took a Bullet for Me!”

August 21st, 1945. A dirt track carved through the dense jungle of Luzon, Philippines. The war is over. The emperor…

The US Army Had No Locomotives in the Pacific in 1944 — So They Built The Railway Jeep

Picture this. It is 1944. You are deep in the steaming, suffocating jungles of Burma. The air is so thick…

Disabled German POWs Couldn’t Believe How Americans Treated Them

Fort Sam Houston, Texas. August 1943. The hospital train arrived at dawn, brakes screaming against steel, steam rising from the…

The Man Who Tried To Save Abraham Lincoln Killed His Own Wife

April 14th, 1865. The story begins with an invitation from President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary to attend a…

End of content

No more pages to load