September 25, 1979, Washington, D.C. The Grand Ballroom of the Hilton sat in shadow—450 living ghosts at round tables under white cloth. Whiskey and cigars perfumed the air as glances traded decades of secrets. These men did not exist on paper; their missions were never documented; their kills were never counted. They were former operatives of the OSS, America’s first organized intelligence agency—the ancestor of the CIA.

In that room sat saboteurs who blew up Nazi trains and assassins who left no trace. Spymasters who turned German officers into assets, parachutists who slipped behind enemy lines, men who killed with their bare hands. They had kept secrets that could topple governments and would die with them. Tonight, they gathered for a reunion—old friends, old rivalries, old ghosts—while dinner plates cleared and hushed war stories drifted.

A man rose—late sixties, silver hair, diplomatic face hiding a harder truth. Those present knew him by reputation, not myth. Douglas Dewitt Bazata, Navy Cross, four Purple Hearts, French Croix de Guerre with two palms. He parachuted into Nazi France, organized 7,000 resistance fighters, killed for his country more times than he could count. He had kept one secret for 34 years and was about to break it.

The room quieted; 450 pairs of eyes locked in. These were men who recognized when words would not be taken back. Bazata cleared his throat, a steady voice shaped by demons he had learned to live with. “I know who killed General George Patton,” he said. Silence became absolute—like a held breath. “I know who killed him,” he continued. “Because I was the one hired to do it.”

No one moved. No one breathed. The most decorated American general of World War II, the liberator of Europe, Old Blood and Guts—claimed murdered by a man in this room. “Ten thousand dollars,” Bazata said. “That’s what I was paid. The order came from the top—General William Donovan, ‘Wild Bill,’ OSS director. He wanted Patton dead. I made it happen.”

Before we go further: we’re a small channel trying to grow by telling untold World War II stories. If you’re enjoying this, please subscribe and drop a comment telling us where you’re watching from. We read every one. Now, back to the confession and the man behind it.

Douglas Dewitt Bazata was born February 17, 1911, in Wrightsville, Pennsylvania. His father was a Presbyterian minister and his grandfather an immigrant from Czechoslovakia. Nothing in his early life suggested he would become one of America’s deadliest instruments. He studied at Syracuse University, then joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1933, serving until 1937.

In 1942, the world changed. America entered the war and the Office of Strategic Services was formed—William “Wild Bill” Donovan’s brainchild and Roosevelt’s answer to centralized intelligence. Donovan recruited the best, the brightest, the most ruthless. Bazata fit the profile exactly, and he was assigned to one of the war’s most dangerous missions: Operation Jedburgh.

Jedburgh teams were triads—typically one American, one British, one French officer—parachuted behind enemy lines to organize resistance against Nazi occupation. Bazata’s team carried the codename “Cedric.” His personal callsign was “Vestre.” In August 1944, Captain Bazata dropped into the Haute-Saône department in eastern France, a landscape riddled with German patrols and collaborators.

Survival odds were slim. One mistake meant capture, torture, death. Bazata did more than survive—he thrived. Within weeks, he had armed and organized 7,000 resistance fighters, planned rail and road sabotage, and rerouted German convoys into ambushes. He operated in civilian clothes, risking execution as a spy if caught. His Distinguished Service Cross citation praised “services reflecting great credit” and adherence to the highest traditions of U.S. armed forces.

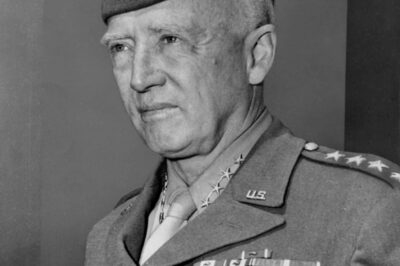

This was not a man prone to fantasy or attention-seeking. When he said he killed, the men in that room had no reason to doubt him. He had killed before, in service, professionally. Which brings us back to December 9, 1945—seven months after Germany’s surrender—when George S. Patton was stationed in Bad Nauheim, commanding the 15th Army.

Patton was restless and enraged, stripped of his Third Army and humiliated by Eisenhower over denazification remarks. He had powerful enemies. He believed the Allies had “defeated the wrong enemy” and argued for pushing the Soviets back before they consolidated Eastern Europe. These were dangerous words—career-killing at best, lethal at worst.

That morning, Patton decided, on short notice, to go pheasant hunting with Major General Hobart Gay after another general canceled a visit. At 11:45 a.m., Patton’s 1938 Cadillac Model 75 traveled near Mannheim in fog and cold. In the back sat America’s most feared general—slapper of cowards, rescuer of Bastogne, man who fancied himself born of ancient warriors.

Then a U.S. Army 2½-ton truck turned left directly into the Cadillac’s path. The collision was minor—light damage, no high speed. The driver, PFC Horace Woodring, was uninjured. General Gay was uninjured. Patton alone suffered catastrophic injury—his neck broken, paralyzed from the neck down. A minor wreck with a single devastating outcome.

Was it coincidence? Bazata said absolutely not. He claimed he tailed the Cadillac with inside knowledge of Patton’s movements. He said Patton stopped to view Roman ruins and, during that pause, Bazata sabotaged the car window so it couldn’t fully close, leaving a four-inch gap. In the instant of collision, amid confusion, Bazata allegedly fired a specialized low-velocity projectile into Patton’s neck—designed to break bone without leaving a bullet.

Patton was taken not to Mannheim’s closer facility but to the 131st Station Hospital in Heidelberg. For twelve days, paralyzed but lucid, he showed some improvement—slight arm movement, stable vitals. He talked of going home for Christmas and told his wife, Beatrice, he’d be back in America soon. Then, on December 21, 1945, he died suddenly—officially of heart failure. No autopsy was performed; Beatrice refused, wishing to spare indignity. Patton was buried among his Third Army soldiers in Luxembourg, as requested.

Bazata’s story did not end at the crash. He claimed a backup plan activated when Patton survived—an NKVD agent known only as “the Pole” infiltrated the hospital and administered a specialized cyanide variant manufactured in Czechoslovakia. Its purpose: induce heart failure or embolism without leaving traces, the perfect poison for the perfect cover. “They botched it the first time,” Bazata said. “They finished the job in the hospital.”

Technical Sergeant Robert L. Thompson, the truck driver, was never charged or court-martialed. He was quietly transferred to England soon after. The official accident report reportedly vanished in postwar bureaucracy—lost, misplaced, perhaps erased. It fed the suspicion, and Bazata’s confession provided a narrative for the absence.

Why would anyone want Patton dead? He was a hero, yes, but a dangerous one to those managing fragile postwar realities. He criticized denazification, admired German military efficiency, publicly embarrassed the Truman administration, and was headed home to retire and write memoirs. He would name names and unravel politics. A living Patton could upend reputations—Eisenhower, Marshall, Donovan. He threatened power not with armies, but with truth.

Donovan, fighting to preserve the OSS as a permanent intelligence force, could ill afford a scandal. The Soviets, fearing Patton’s willingness to push east to Moscow, saw him as an existential threat. A dead Patton simplified many problems, for many people. Bazata passed a lie detector test for Spotlight magazine in 1979 and repeated his confession several times. He supplied details that sounded like insider knowledge. He never recanted.

Bazata died July 14, 1999, at 88, buried in Arlington among American heroes. His New York Times obituary noted his OSS service and artistic career, not Patton. His confession has never been proven—but never fully disproven. No autopsy. Missing accident report. A truck driver transferred, then forgotten. A confession from a man many in that room believed capable.

Was George Patton murdered? Was Douglas Bazata telling the truth—or spinning bitterness into legend? The evidence is circumstantial; witnesses are gone; truths lie in classified files of agencies that insist they don’t exist. But one thing is indisputable: on September 25, 1979, a decorated American war hero stood before 450 of the most dangerous men alive and confessed to assassinating the most legendary general of World War II.

No one called him a liar. Murder or coincidence? Tell me what you think in the comments. And if you want more deep dives into the mysteries of World War II, subscribe—so we can keep bringing the untold stories to light.

News

Why Patton Was the Only General Who Predicted the German Attack

– December 9, 1944. A cold Monday morning at Third Army headquarters in Nancy, France. Colonel Oscar Koch stood before…

What German High Command Said When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

– “Impossible. Unmöglich.” That word echoed through German High Command on December 19, 1944. American General George S. Patton had…

Patton (1970) – 20 SHOCKING Facts They Never Wanted You to Know!

– Behind the Academy Award-winning classic Patton lies a battlefield of secrets. What seemed like a straightforward war epic is…

George S. Patton’s Victories Don’t Excuse What He Did

When disturbing allegations about George S. Patton surfaced, his daughter fiercely defended him. Only after her death did her writings…

Was General Patton Silenced? The Death That Still Haunts WWII

Was General Patton MURDERED? Mystery over US war hero’s death in hospital 12 days after he was paralyzed in an…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

June 1979, Newport Beach, California. Four days after John Wayne’s funeral, the house felt hollow—72 years of life reduced to…

End of content

No more pages to load