17th April 1945.

A muddy roadside near Heilbronn, Germany.

Nineteen‑year‑old Luftwaffe helper Anna Schaefer is captured alone. Her uniform is torn, her face streaked with blood and dirt. She has been hiding in a ditch for three days after her unit surrendered.

A U.S. 100th Infantry Division patrol finds her. Private First Class Vincent “Vinnie” Rossi from Brooklyn, 22, Italian American, who speaks a little German from his nonna, is the first to reach her.

Anna throws up her hands and screams in terror.

“Bitte, tun Sie mir nichts… please don’t kill me.”

Vinnie raises his rifle, then sees the raw fear in her eyes and lowers it. He steps closer. Anna squeezes her eyes shut, waiting for the worst.

Instead, she hears fabric ripping. She opens her eyes in panic. Vinnie has torn open the back of her shredded uniform jacket—not for assault, but to reveal a massive infected shrapnel wound she has been hiding for days.

The wound is green, pus‑filled, crawling with maggots. Vinnie swears in Italian, then yells for the medic. Within minutes, the patrol medic, Corporal Daniel Goldstein—Jewish, escaped Vienna in 1938—is on his knees, cleaning the wound with sulfa powder and morphine.

Anna is shaking, half from fever, half from disbelief. Daniel looks up at Vinnie. “This girl’s got three, maybe four hours before sepsis kills her.” Vinnie doesn’t hesitate.

He lifts Anna in his arms. She weighs nothing. He starts running toward the aid station two miles away. The entire patrol runs with him.

They take turns carrying her. When she tries to thank them in broken English, Vinnie just says, “Save your breath, kid. We’re getting you fixed.”

At the field hospital, surgeons operate for six hours. They remove 14 pieces of shrapnel and half her left shoulder blade. She wakes up three days later in a clean bed, IV in her arm, real pajamas, a teddy bear someone left on the pillow.

Vinnie is asleep in a chair beside her, still in muddy boots. When she stirs, he wakes instantly. Anna whispers, “You tore my dress.”

Vinnie turns red. “To save you, stupid. Not… not the other thing.” Anna starts laughing—weak, painful, but real laughter. For the first time in years.

Six months later, October 1945.

Anna, now walking with a cane, is released from the hospital. Vinnie has extended his tour twice just to visit her every weekend.

On her last day, he arrives with a small box. Inside, a brand‑new dress, sky blue, bought with six months of poker winnings.

He kneels—awkward, clumsy. “Anna Schaefer, I tore your dress once to save your life. Now I’m asking… can I put a new one on you for the rest of mine?”

Anna cries so hard the nurses think something is wrong. She says yes in three languages. They marry in the hospital chapel, April 1946.

Vinnie carries her over the threshold because her leg still hurts in the rain. They name their first daughter Margaret, after the nurse who helped save Anna.

Every year on the 17th of April, Anna wears the blue dress. Every year, Vinnie tells the same joke: “I’m the only guy who tore a girl’s clothes off on the first date and still got a yes.”

Their grandchildren roll their eyes, but they never stop smiling. Because sometimes the moment you expect violence becomes the moment you find forever—all because one soldier tore the right thing for the right reason.

17th April 1995.

Stuttgart. A cemetery. Dawn.

Anna Rossi, 69, stands alone before Vinnie’s grave. Cane in one hand, small cloth bag in the other. She opens the bag with shaking fingers.

Inside: the sky blue dress from 1946. Still perfect. Still the color of that first morning she felt human again. She spreads it over the stone like a blanket.

Then she takes out one more thing: the blood‑soaked scrap of her 1945 uniform, the piece Vinnie tore open to save her life, preserved in glass. She lays it on the blue silk.

“Vinnie,” she whispers, voice cracking. “You tore my dress once to give me tomorrow. I wore the new one every 17th April for 49 years. Today I bring both back… so you know I never forgot.”

She kneels, kisses the stone, and starts crying the way she did the day he proposed in the hospital ward. A groundskeeper watches from afar, tears rolling.

Anna stands, salutes American‑style, and walks away. The blue dress stays on the grave all summer. Rain, sun, wind—it never fades.

Every 17th April after that, strangers find a fresh blue ribbon tied around the stone and one red rose. No one ever sees who leaves them.

They only know an old woman with a cane comes once a year, touches the stone, and smiles like she’s 19 and in love again. Because some dresses are not fabric. They are the exact moment someone chose life for you.

And some love stories don’t end at death. They just change color—from blood to sky blue—and keep shining.

News

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Boot Lace Trick” Took Down 64 Germans in 3 Days

October 1944, deep in the shattered forests of western Germany, the rain never seemed to stop. The mud clung to…

“Never Seen Such Men” – Japanese Women Under Occupation COULDN’T Resist Staring at American Soldiers

For years, Japanese women had been told only one thing about the enemy. That American soldiers were merciless. That surrender…

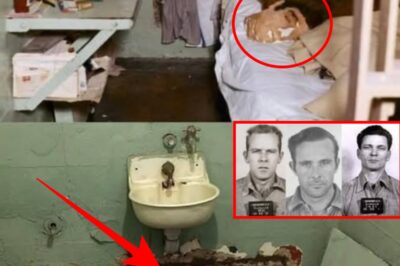

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

End of content

No more pages to load