April 17, 2018 began like thousands of other flights.

Southwest Flight 1380 lifted off from New York’s LaGuardia Airport under a clear sky, climbing steadily toward cruising altitude. The cabin settled into routine. Seatbelts clicked open. Passengers checked phones, closed eyes, planned the rest of their day.

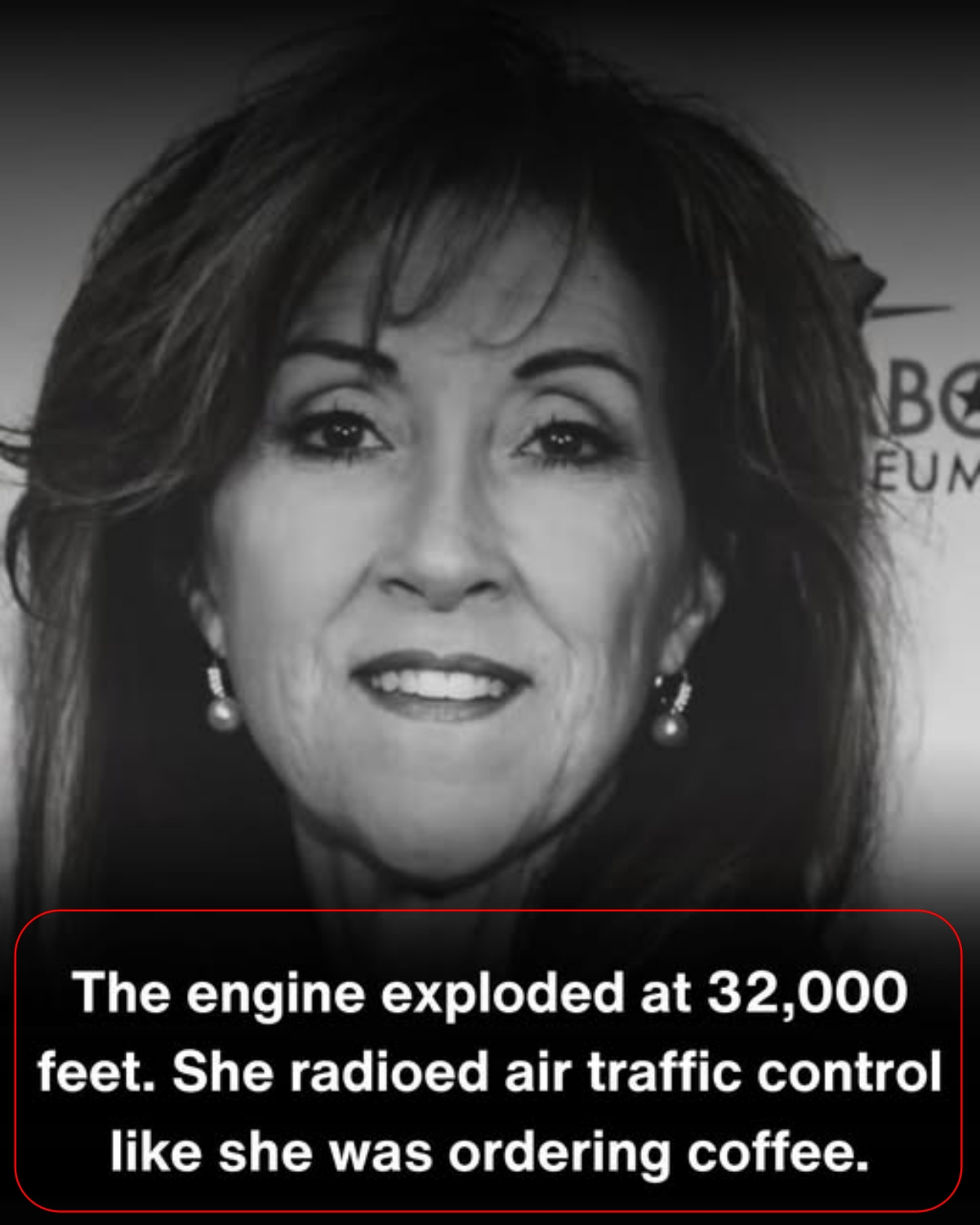

At the controls sat Captain Tammie Jo Shults.

She had flown this airplane countless times. A Boeing 737 was familiar, almost comforting. Years of experience had trained her body to sense the aircraft’s moods — the subtle vibrations, the pressure in the yoke, the rhythm of the climb.

Nothing felt wrong.

Then, without warning, the left engine exploded.

Not failed.

Not flamed out.

Detonated.

The blast was so violent that Shults’ first instinct wasn’t engine failure. It was collision. For a split second, she believed another aircraft had struck them midair.

Metal tore through the nacelle. Shrapnel ripped outward with unimaginable force. Pieces of the engine became weapons, punching through the fuselage like bullets.

One of them struck Window 14A.

The window vanished.

The cabin depressurized instantly — a violent, explosive release of air that physics does not negotiate with. The pressure differential created a force stronger than human grip.

Jennifer Riordan, seated next to that window, was pulled toward the opening.

Passengers screamed.

Hands reached out. People grabbed her arms, her torso, her clothing — fighting against forces that no human body was meant to resist. They anchored her, holding her back from being completely pulled out of the aircraft.

Oxygen masks dropped from the ceiling.

The plane rolled.

The nose pitched down.

Inside the cockpit, warning lights cascaded across the panel — systems failing in rapid sequence, alarms competing for attention, the aircraft itself fighting every control input.

Smoke filled the air.

Below them, terrified passengers typed final messages to spouses, children, parents.

And in the middle of all of it, Tammie Jo Shults reached for the radio.

Her voice did not shake.

“Southwest 1380, we’re single engine. We have part of the aircraft missing, so we’re going to need to slow down a bit.”

Air traffic controllers paused.

They could hear the alarms in the background. They knew what had just happened. Yet the voice on the other end of the radio was steady — almost conversational.

She wasn’t panicking.

She was flying.

That calm did not come from nowhere.

It was built — piece by piece — across a lifetime of being told she did not belong where she insisted on going.

The Girl Who Watched the Sky

Tammie Jo Shults grew up in New Mexico, where the sky feels endless and fighter jets cut across it like signatures of possibility.

She watched them tear overhead and felt something settle into her bones.

She wanted to fly.

Not recreationally.

Not casually.

She wanted to be in those aircraft — responsible for them, commanding them.

At a high school aviation lecture, she sat among a room full of boys. When the speaker, a retired Air Force colonel, scanned the audience, he paused.

He asked if she was in the wrong room.

She wasn’t.

When she told him she wanted to be a pilot, he didn’t mock her. He simply stated what he believed was reality.

There were no professional women pilots.

Women didn’t fly fighter jets.

The military wasn’t interested.

She should be realistic.

Tammie Jo Shults listened.

And then she ignored him.

Closed Doors, Over and Over Again

Reality, as it turns out, pushed back hard.

The Air Force rejected her.

Then rejected her again.

Then rejected her a third time.

The Navy told her she scored well enough — for a man. For a woman, the standards were higher.

Recruiters declined to even submit her paperwork. One year passed before she found someone willing to process her application.

Every rejection delivered the same message in different language:

You are not supposed to be here.

But persistence is its own qualification.

Eventually, the system cracked open just enough.

She was accepted.

And once inside, she did not simply keep up.

She excelled.

Breaking the Sound Barrier — and Expectations

Shults became one of the first women to fly the F/A-18 Hornet in U.S. Navy service — a frontline fighter jet that does not forgive hesitation.

It demanded precision. Discipline. Calm under pressure.

She delivered all three.

Yet even competence did not shield her from resistance.

At one point, a commanding officer refused to allow a woman to teach advanced aerial gunnery. The message was clear: certain roles were still not meant for her.

Instead, she was reassigned.

Out of Control Flight recovery.

It was not presented as an opportunity.

It was a sidelining.

The course focused on something no pilot wants to experience — spins, dives, catastrophic failures. Situations where instruments lie, systems cascade into collapse, and the aircraft no longer behaves according to the book.

For a year, she taught pilots how to survive when everything goes wrong.

How to let go of the illusion of control.

How to feel the aircraft instead of forcing it.

How to recover when panic is the real enemy.

She would later say:

“I learned I don’t have to be in control all the time to get back into control.”

At the time, it felt like punishment.

In truth, it was preparation.

Back to April 17, 2018

The Boeing 737 was fighting her.

With one engine gone and part of the fuselage missing, the aircraft wanted to roll. It wanted to dive. It resisted stabilization.

Shults did not wrestle it.

She listened to it.

She used instinct refined by years of flying on the edge — by countless hours spent teaching others how to recover from the unrecoverable.

The aircraft descended more than 20,000 feet in minutes, yet never became uncontrollable.

She coordinated with her first officer. She spoke clearly to air traffic control. She prioritized what mattered — aircraft control first, communication second, everything else later.

The runway at Philadelphia International Airport came into view.

She landed the crippled plane.

Not dramatically.

Not heroically.

Precisely.

After the Wheels Stopped

Emergency crews rushed the aircraft.

Jennifer Riordan would later die from her injuries.

One hundred forty-eight other passengers survived.

After landing, medics checked Shults’ vital signs.

Her heart rate had barely elevated.

The adrenaline that should have flooded her system never fully took over.

She had been here before — not in circumstance, but in mindset.

Before leaving the aircraft, she walked the cabin.

She hugged shaking passengers. Looked them in the eyes. Told them they were safe.

She stayed until they believed her.

Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who had once guided an Airbus onto the Hudson River, called her personally.

Pilot to pilot. Survivor to survivor.

He knew exactly what it took to sound calm when chaos demanded otherwise.

The Long Road to Belonging

Years earlier, recruiters had dismissed her. Commanders had tried to ground her. Assignments meant to humiliate her had reshaped her skills instead.

Every barrier had failed to change what she already knew.

She belonged in the cockpit.

On April 17, 2018, when metal tore through her aircraft and passengers prepared for the worst, the world heard what belonging sounded like.

It sounded calm.

Measured.

Unbreakable.

A voice that did not rise, even when everything else fell.

Because she had spent thirty years preparing for a moment she hoped would never arrive.

And when it did, she was ready.

One hundred forty-eight people are alive today because she refused to accept “no” as the final answer.

She had always belonged in the sky.

And when the sky tested her, she proved it.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load