The conference room smelled like old wood and expensive cologne. I sat at a long mahogany table, hands folded, watching my sister Brenda fidget with her pearls. My parents flanked her, faces set in righteous certainty. “We have evidence,” my mother announced to the three-member panel, accusing me of practicing law without passing the bar. I stayed silent, exactly as my attorney, Graham, advised: let them talk, let them feel confident.

Judge Patricia Morland presided, with senior partner Thomas Ashford on one side and Detective Lawrence Brennan on the other. Brenda leaned forward, painting me as the lifetime disappointment who could never pass the Massachusetts bar. My father nodded, playing the saddened parent forced to act for the public good. Judge Morland opened my file—and froze. “Miss Hamilton,” she said slowly, “you argued before me last year, the Fitzgerald case.”

The room went silent. “I called it the most brilliant defense I’ve seen in 30 years,” she continued. “Why is your family claiming you’re not licensed?” My mother’s face paled; Brenda’s mouth opened and closed without words. “Perhaps,” I said softly, “we should start at the beginning.” I grew up in Brenda’s shadow—blonde, willowy, Yale golden child—while I was the late “oops” baby who scrambled for every B-minus.

At sixteen, I served appetizers at Brenda’s Yale Law celebration while my mother predicted I’d attend community college and study something “practical.” Brenda laughed and patted my shoulder: “There’s no shame in knowing your limitations.” Something hardened in me. I left for Lakewood Community College in Ohio with a $2,000 check—“all we can afford”—while Brenda’s tuition ran $60,000 a year. Away from comparisons, I thrived.

Professor Ruth Anderson, a former prosecutor teaching paralegal studies, saw what my family never did. “You have a natural instinct for legal reasoning,” she told me, and pushed me to consider law school. I graduated with perfect grades, earned a full scholarship to Suffolk Law, and worked myself raw. The first year was brutal; I lived on ramen and slept four hours a night. By second year, it clicked: patterns, arguments, strategies.

I made law review, won academic awards, and landed a criminal defense internship. My parents didn’t come to my graduation; Brenda’s wedding took priority. Professor Anderson flew in and cheered. I passed the bar on my first try, scoring in the top 5%. When I called my parents, my mother said they were busy with Brenda’s nursery. They never called me back.

Criminal defense became home. Frank Morrison—grizzled, sharp, relentless—taught me juries, evidence, and how to fight for people the system discards. I prepared cases like each was my last. Judges recognized me; other attorneys referred clients. Then came the Fitzgerald case—$3 million embezzlement, an airtight-looking prosecution. I found the timeline cracks, manipulated wire transfers, and a supervisor fleeing to the Caymans. The jury acquitted on all counts.

Afterward, Judge Morland called my defense the most brilliant she’d seen. Offers and invitations followed; my reputation grew. Two years later, Frank made me named partner. My family still treated my career like a vague hobby. At a cousin’s wedding, my mother introduced me as “someone who does legal work with criminals” while glowing over Brenda’s Manhattan partnership. I mentioned winning the Moray case. “That’s nice,” Brenda said. “I’m sure it felt like a big deal.”

Four months later, Graham called: my parents and Brenda had filed a complaint with the State Bar, accusing me of falsifying credentials and forging bar passage. They included old report cards, affidavits of “struggles,” and Brenda’s narrative that I was delusional, impersonating an attorney to compete with her. The hearing was scheduled. We prepared meticulously, knowing even false accusations can stain reputations.

My family’s lawyer performed theatrically, painting me as dangerous and desperate. Brenda spoke of my “troubled” past; my parents described me as unstable, unable to distinguish reality from fiction. I didn’t react. Then Graham presented the truth: Suffolk transcript, bar certificate, license, judicial commendations, case records. Ashford’s skepticism shifted to confusion. Detective Brennan frowned. The evidence contradicted every claim.

Judge Morland opened the detailed case file and stopped breathing for a beat. “You argued before me,” she said, “and I praised your defense.” Graham laid out my wins, settlements, and peer references. Detective Brennan reminded them that filing false complaints is a crime and potentially defamatory. Ashford asked my family if they’d verified anything before signing affidavits. They hadn’t.

I spoke plainly. My family dismissed me for years—funding Brenda lavishly while giving me $2,000 and disdain, skipping my graduation for her wedding, ignoring my cases even when covered in the Boston Globe. This complaint wasn’t civic duty. It was retaliation because the daughter they called a disappointment succeeded without their help or approval. The panel’s faces told the rest.

“This hearing is concluded,” Judge Morland said. “We find no evidence supporting these allegations. Your credentials are impeccable; your record is outstanding. This complaint is malicious and without merit.” She warned of consequences; Ashford reported Brenda to the New York Bar. Detective Brennan escorted my parents for questioning. Then, in a quiet moment, Judge Morland apologized—and nominated me for the Professional Excellence Award.

The aftermath was swift. My parents faced public embarrassment and investigation; the local paper ran the story. Brenda received a formal reprimand and mandatory ethics training; her reputation suffered, and her firm suggested a leave. When their lawyer offered hush money and an NDA, I refused. Money doesn’t buy the truth from people who tried to bury it.

Months later, my parents called—stiff, formal, asking me to “use my connections” to help Brenda find a new job. They framed their actions as “overreacting.” I said no. Family doesn’t file false accusations to destroy careers, then ask for favors. Choices have consequences. The call left me strangely free.

Two years after the hearing, Brenda emailed from a personal account: “I’m sorry.” She wrote about losing her job and marriage and finally confronting why she tried to tear me down—jealousy, identity, threat. She admitted she saw me succeed without advantages and couldn’t bear it. I believed the apology was real. I didn’t respond. Sincerity doesn’t erase harm.

Five years later, Suffolk invited me to speak at graduation. I told the back-row students—the tired ones, the first-generation lawyers—that success without connections is earned and valid. “Their opinion isn’t the truth,” I said. “Your work is the truth. Your cases, your license—hold on to that.” The applause felt like a long overdue recognition.

Ten years later, my firm had fifteen attorneys, representing clients the big shops ignore and changing lives one case at a time. Frank retired to fish in Maine; Professor Anderson passed, leaving a note: “I always knew you’d make it.” I never reconciled with my parents. Brenda stopped emailing. My life filled with work that mattered, friends who valued me, and a rescue dog named Justice asleep under my desk.

One afternoon in court, I saw my mother in the back row—smaller, fragile, watching silently. I won the motion; when I turned, she was gone. Maybe curiosity, maybe realization. It didn’t matter. I walked into the bright Boston afternoon to celebrate with my team and return to the dozen cases waiting. I had built a life worth living.

They tried to erase me—reduce me to the disappointment daughter with “limitations.” They failed. I was Attorney Hamilton: named partner, award winner, mentor, advocate—the lawyer Judge Morland called brilliant. I became exactly who I was meant to be. And I got there all by myself.

News

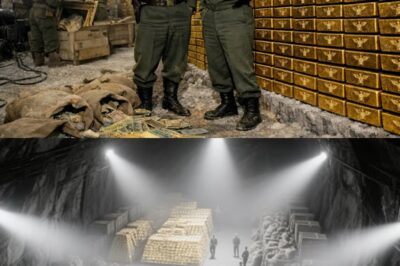

What Patton Found in This German Warehouse Made Him Call Eisenhower Immediately

April 4th, 1945. Merkers, Germany. A column of Third Army vehicles rolled through the shattered streets of another liberated German…

What MacArthur Said When Patton Died…

December 21, 1945. Tokyo, Japan. General Douglas MacArthur sits in his office in the Dai-ichi Seimei Building—the headquarters from which…

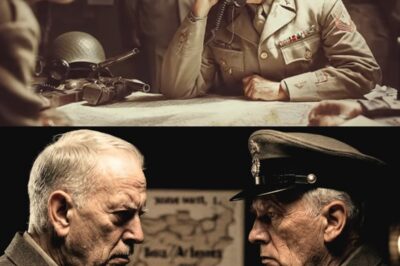

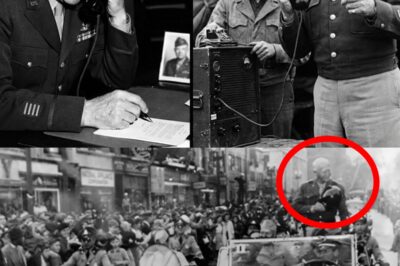

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne

If Patton hadn’t moved in time, the 101st Airborne wouldn’t have been captured or forced to surrender. They would have…

The Phone Call That Made Eisenhower CRY – Patton’s 4 Words That Changed Everything

December 16, 1944. If General George S. Patton hadn’t made one phone call—hadn’t spoken four impossible words—the United States might…

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

End of content

No more pages to load