The water was the same deep, indifferent blue it had always been. The waves rose and fell with ancient rhythm. The sun beat down without mercy.

It was the human beings trapped on the ship who understood how close they were to disappearing.

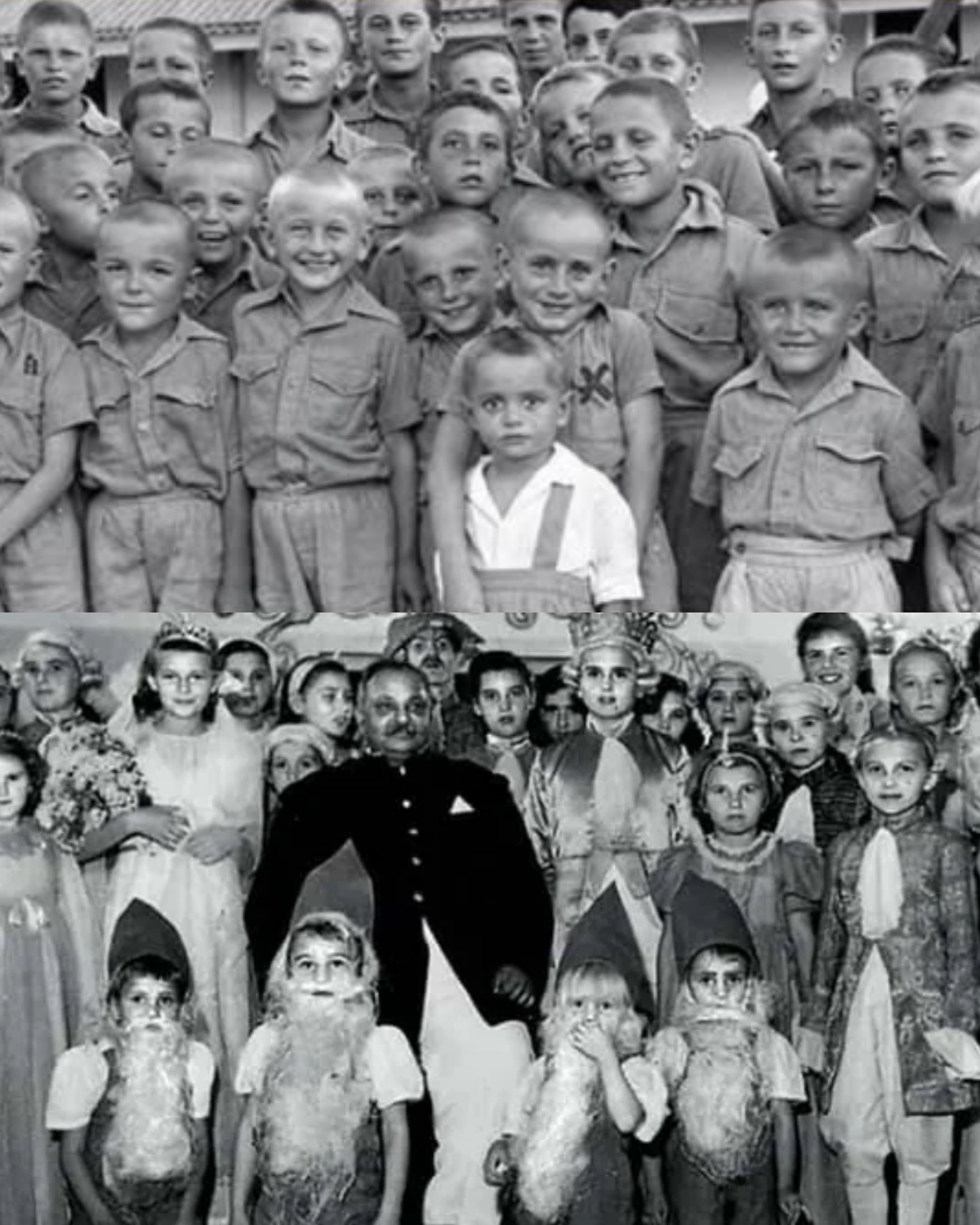

740 children on a ship no one wanted

The ship moved slowly, almost aimlessly, in the Arabian Sea.

On its decks: 740 children.

Polish children.

Orphans.

They had already survived more than most adults could endure.

They had come out of Soviet labor camps—those vast, cold places where people disappeared and hope froze. Their parents had died of influenza, of exhaustion, of starvation, of unnamed illnesses that come when humans are treated as disposable.

Some of the children remembered the sound of guards’ boots in the snow.

Some remembered the rasp of their mother’s breath as it grew weaker.

Some remembered the moment they realized: there would be no more “Mama” or “Tata” to run to.

They had somehow gotten out of the camps, part of the wave of Polish civilians who were released after the Sikorski–Mayski agreement and made their way, half‑starved, through Central Asia toward Iran.

Iran had been a doorway, a new landscape of dust and heat instead of snow and ice. But it was not a final destination. Not for them.

They were children without parents, without a home, without a country that was truly theirs anymore. Poland was under occupation. The world map had turned against them.

So they were put on a ship and sent away, toward British‑controlled India. Toward, they were told, safety.

But no one had told them what happens when safety is measured in paperwork and politics instead of human lives.

“Not our responsibility. Sail away.”

The British Empire in 1942 was vast—spanning continents, ruling millions. It controlled oceans, railroads, customs, ports.

On paper, it was the greatest power in the world.

And yet, when this one ship, full of exhausted Polish children, appeared off the Indian coast, the answer that came from power was not protection.

It was rejection.

Port after port along the Indian coast refused entry.

No room.

No capacity.

Not our responsibility.

Sail away.

The reasons were phrased in bureaucratic language: wartime strain, limited resources, political complications. But to the children on deck, none of that mattered. What they understood was simpler:

Every door was closed.

The food stores were running low. The dried bread, the watery soup, the occasional fruit—all of it was disappearing faster than it could be replaced.

There was little medicine left.

Coughs spread quickly. Small wounds festered. Fever came, stayed.

On board, twelve‑year‑old Maria held her six‑year‑old brother’s hand.

Before their mother died in the labor camp, she had looked at Maria—eyes already clouded with sickness—and said the words that still echoed in the girl’s mind:

“Take care of him. Promise me.”

Maria had promised. She had meant it with all the ferocity of a child who still believed that promises could change reality.

But how do you protect someone when the ocean surrounds you, the decks creak beneath your feet, and country after country turns its back?

The adults aboard tried to keep the children calm. They sang songs in Polish. They told stories. They rationed food. They avoided letting the children see the desperation in their faces.

And all the while, the ship drifted—rejected, unwanted, a floating coffin waiting for time to close the lid.

A minor prince in a controlled kingdom

Hundreds of miles away, in the princely state of Nawanagar in the Kathiawar peninsula of Gujarat, India, news traveled by cable and messenger.

It reached a palace that was modest by the standards of empire, but grand compared to the villages around it.

The ruler there was Jam Sahib Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji—Maharaja of Nawanagar. A “Jam Sahib” in title, a “Minor Prince” in the complex hierarchy of the British Raj.

The British controlled:

– The railroads.

– The ports.

– The army.

– Foreign policy.

He controlled, formally, his own small state. Informally, he controlled much less than his ancestors had.

He had every reason to keep his head down. India was under British rule. World War II raged. The British government could reward loyalty and crush dissent.

Jam Sahib had served in the British Indian Army. He was not a revolutionary. He understood the balance of power—and the consequences of upsetting it.

So when his advisors brought him the report—740 Polish children stranded at sea because no port in British‑controlled India would accept them—they expected him to frown sympathetically, maybe write a letter, maybe ask for information.

They did not expect what he did next.

“They do not control my conscience.”

“How many children are there?” Jam Sahib asked.

“Seven hundred and forty, Your Highness.”

There is a particular kind of silence that falls when a decision is being made inside a person, and everyone in the room knows it.

He paused.

“The British may control my ports,” he said slowly, “but they do not control my conscience.”

Then he gave the order that would echo through generations:

“Those children will dock at Nawanagar.”

The advisors were alarmed.

“Your Highness, if you challenge the British—”

He cut them off.

“So be it.”

He understood what he was doing. Britain was not just any government; it was *the* imperial power ruling over 400 million Indians. Defying its wishes—especially on an issue that touched on immigration, war policy, and international agreements—was not a casual act.

British officials protested. They reminded him of protocols, of jurisdiction, of wartime procedures. They reminded him who commanded the navy and who controlled the ports.

He did not back down.

“If the strong refuse to save these children,” he said, “then I, the weak, will do what they cannot.”

He sent word to the ship:

You are welcome here.

A signal went back across the water, carried by military channels, relayed to the captain who had been waiting, hoping, beginning to despair.

For the first time in days, the ship had a destination that was not “away.”

The day the ship arrived

August 1942. Summer in western India.

The heat pressed down on everything like a hand. The harbor glimmered under a cruel sun. The air smelled of salt, tar, sweat, and the faint sweetness of fruit from nearby markets.

People on the docks watched as the ship approached, moving slowly, tired as the children it carried.

From a distance, it looked like any other vessel. Up close, it became something else:

A question.

A test.

A verdict on what human beings would choose to do when offered the chance to act.

The children disembarked.

They did not bound down the gangplank like excited travelers.

They moved like ghosts.

Some were carried, too weak to walk.

Some shuffled, their feet dragging, clothes hanging loosely on frames that had lost too much weight too quickly.

Eyes that should have been full of mischief and light were blank, watchful, or simply empty.

Hope was dangerous; they had learned that. Hope had hurt too many times.

On the dock, waiting for them, stood the Maharaja.

He was not hidden behind officials. He was not observing from a distance.

Dressed simply in white, he stepped forward—one man in the sun, in front of children who had been pushed into the shadows for too long.

He did something small but powerful: he knelt down to their eye level.

He did not look down on them. He met them where they were.

With the help of interpreters, he spoke words they had not heard since their parents died, words most of them had never expected to hear again from any adult in power.

“You are no longer orphans,” he told them.

“You are my children now.

I am your *Bapu*—your father.”

Twelve‑year‑old Maria felt her brother’s small hand tighten around hers.

She did not fully understand the language, but she understood the tone. The way he looked at them as if they were not a problem, not a burden, not a mistake, but something precious.

After months of being unwanted, the words seemed unreal.

Dangerous, even. Like a dream that would break if she believed in it.

But the Maharaja was not playing at kindness.

He meant every word.

Not a camp. A home.

He could have set up a standard refugee camp: rows of temporary tents, a few overworked officials, just enough resources to keep the children alive and nothing more.

He refused to do that.

In the coastal village of Balachadi, he created something extraordinary: a piece of Poland transplanted into Indian soil.

Balachadi was originally his summer palace area—near the sea, with open land. There, under palm trees and wide skies, he ordered the construction and adaptation of buildings to house the children.

He made sure they had:

– Proper dormitories, not overcrowded barracks.

– Classrooms, not just open spaces.

– A small chapel, because he knew their faith mattered.

– Playing fields and gardens, because childhood needs more than shelter and food.

He worked with Polish authorities and relief organizations to bring in Polish teachers, staff, and caregivers—people who understood not just the language, but the wounds.

Polish was spoken in the classrooms. Polish songs were sung under the Indian sun. Polish holidays were marked with as much authenticity as possible.

At Christmas, under tropical skies where snow never fell, they decorated a Christmas tree. The setting was strange, but the ritual was familiar. It stitched their broken sense of identity back together.

Meals were designed to taste like memory.

Indian cooks worked with Polish staff to create food that felt like home as much as circumstances allowed. In the kitchens, spices from India met recipes from Poland. It was an unlikely fusion, born not of trend but of necessity and love.

“Suffering tries to erase you,” the Maharaja said.

“But your language, your culture, your traditions are sacred. We will keep them here.”

He didn’t see these children as cheap labor, as charity cases, or as a political tool.

He saw them as future adults who deserved to remember who they were.

Children learning to laugh again

For the first time in years, the children of Balachadi had:

– Regular meals

– Clean clothes

– Beds of their own

– Teachers who believed they had a future

– Doctors who treated their illnesses before they became fatal

Maria watched her little brother chase a peacock through the palace gardens—his thin legs pumping, his laughter bright in the hot air.

Her body did something strange: it relaxed.

Muscles that had been tight since the camps, tight on the ship, tight every time someone said “no,” began to remember what it felt like to stand without bracing for the next blow.

She went to school again—sat at a desk, opened a book, wrote her name. The chalk felt foreign between her fingers, as if it belonged to a past life.

Children who had grown used to standing in lines—lines for food, lines for inspection, lines for survival—now stood in lines for games, for classes, for theatre rehearsals.

They learned math. History. Literature.

They played football on dusty fields, screamed with delight when someone scored, sulked when they lost a game. They put on plays and sang in choirs.

In the evenings, they wrote letters to the Red Cross, hoping against hope that someone, somewhere, might know if an aunt, a cousin, a neighbor was still alive.

Balachadi became their world.

It was a world held together by the stubborn conviction of one man: that compassion was not a luxury, not a weakness, but a duty.

A king who remembered birthdays

The Maharaja did not simply sign orders and disappear.

He visited often.

He walked the grounds, not as a distant monarch, but as someone who wanted to check, personally, that the children were truly well.

He learned names.

He remembered faces.

He showed up at birthday celebrations, clapping as children blew out candles on small cakes. He watched their theatre performances, smiling when they forgot their lines and cheering when they finished.

When children cried at night, missing parents who would never return, he made sure there were adults to hold them, to sit by their beds, to listen to the sobs that came not from scraped knees but from a loss that had no bandage.

He paid for doctors, teachers, clothing, and food from his own wealth. This was not a line item in someone else’s budget. It was personal.

For four years—while bombs fell on cities, armies clashed, borders shifted, and the world tore itself apart—Balachadi remained a place where 740 children were allowed to be what they almost had been denied the chance to be:

Children.

Not statistics.

Not “refugee count: 740.”

Children.

The war ends. The hardest goodbye.

Wars end on paper before they end in people’s lives.

By 1945, the tide had turned. By 1947–48, the map of Europe was being redrawn. Discussions began about repatriation and resettlement. The Polish children in Balachadi were told the news:

They would have to leave.

Some would go to newly liberated—and soon, Soviet‑controlled—Poland. Others would eventually resettle in places like the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia.

The announcement ripped through the colony like a storm.

For many of these children, Balachadi was the only stable home they remembered. Poland was an idea, a memory, a story told by adults. India—the palace, the school, the gardens, the peacocks—that was reality.

The idea of leaving the Maharaja, their teachers, their friends, the only “father” many of them felt they had now—it was almost unbearable.

They wept.

They wrote letters of thanks. They drew pictures. They tried, in clumsy handwriting and halting words, to express something no language fully captures: gratitude for being seen as human when the world had treated them as excess.

The day they left, the platforms were crowded with children clutching suitcases, small bags, photos, pieces of Balachadi they tried to hold on to.

The Maharaja was there.

He watched them go with eyes that, witnesses recall, were filled with emotion he did not entirely hide.

He had given them what he could.

Now he had to let them go.

The children grow up—but never forget

Time did what it always does. It moved forward.

The children of Balachadi grew up, scattered across the globe.

They became:

– Doctors

– Engineers

– Teachers

– Artists

– Parents

– Grandparents

They built careers, raised families, paid taxes, argued about politics, worried about their children’s futures.

But buried in their lives, like a bright shard of glass that never dulled, was the memory:

Of a ship that no one wanted.

Of a dock where one man waited.

Of a voice saying, “You are my children now.”

When they told their own grandchildren bedtime stories, some didn’t start with fairy tales.

They started with:

“There was once an Indian king…”

In Poland, as the decades passed and the country shifted from occupation to communist rule to eventual freedom, the story of Jam Sahib Digvijaysinhji did not fade.

Streets and squares were named in his honor.

One of them: Good Maharaja Square in Warsaw—“Skwer Dobrego Maharadży.”

Schools bore his name.

Books were written.

Documentaries filmed.

He was posthumously awarded Poland’s highest honors.

But the first monument to him was not made of bronze or stone.

It was made of 740 lives that continued.

Lives that could have ended namelessly on a ship the world had decided not to see.

The quiet weight of one decision

History often celebrates loud heroes:

Battlefield commanders.

Revolutionary leaders.

Orators whose voices echo across stadiums.

Jam Sahib’s heroism did not come with trumpets. There were no dramatic speeches broadcast across continents. No headlines shouting his name in 1942.

What he did was, on paper, simple:

He saw human beings in danger.

He had the power to help.

He chose to help.

He did this at a time when many people with far more power chose not to.

He was not obligated. Those were not his citizens, not his subjects, not his co‑religionists, not his compatriots. He had every rational excuse to say:

“This is not my problem.”

Instead, he said:

“They are my children now.”

In the balance of global politics, his act did not change the outcome of the war. It did not redraw maps. It did not topple governments.

But for 740 people, it was the difference between an unmarked grave in the sea and a life.

And those 740 lives rippled outward, across continents and generations, in ways no one could have plotted on a military map.

The world changed—quietly, forever

Today, many of those children are gone. The ones who remain are in their eighties and nineties.

They gather, when they can. They share old photos: black‑and‑white images of small faces in the Indian sun, uniforms too big, smiles too unsure.

They tell their grandchildren about Balachadi:

About mangoes, the taste of which shocked their winter‑trained tongues.

About peacocks strutting in the gardens of a palace owned by a man who refused to act like a distant ruler.

About Christmas without snow, but with songs and candles and the same old carols.

About the day they arrived in a place that felt like the end—and discovered it was, instead, a beginning.

They tell them about an Indian king who refused to let compassion be negotiated away.

Jam Sahib Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji lived the rest of his life in India, saw his country move toward independence, saw the British Empire that once intimidated his advisors begin to crumble.

He did not live to see all the ceremonies and memorials built in his honor in Poland. He did not act for medals or for monuments.

He acted because, in 1942, when the world was on fire and many of the strong were choosing calculation over conscience, he decided that being human mattered more than being powerful.

When 740 children died at sea and every country said “no,” one man—who had every reason to remain silent—said “yes.”

And because he did, the world did not end for them.

It grew.

Quietly.

Forever.

News

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Boot Lace Trick” Took Down 64 Germans in 3 Days

October 1944, deep in the shattered forests of western Germany, the rain never seemed to stop. The mud clung to…

Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open

17th April 1945. A muddy roadside near Heilbronn, Germany. Nineteen‑year‑old Luftwaffe helper Anna Schaefer is captured alone. Her uniform is…

“Never Seen Such Men” – Japanese Women Under Occupation COULDN’T Resist Staring at American Soldiers

For years, Japanese women had been told only one thing about the enemy. That American soldiers were merciless. That surrender…

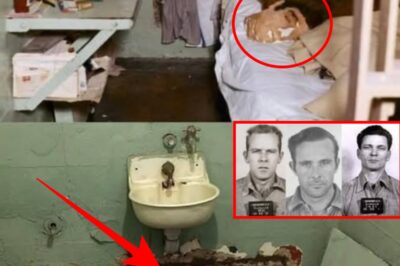

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

End of content

No more pages to load