“To say about me: I love to sing and I love women.” Dean Martin wasn’t just a singer or actor—he was a whole mood. Cool, calm, and endlessly collected, he ruled Hollywood with a drink in his hand and a joke on his lips. Behind that easy charm, though, was a life marked by pain, loss, and quiet suffering. He climbed to the top, but the price was heavy—complicated love, the tragic death of his son, and later, the loss of his beloved wife—leading up to his own passing in 1995.

The boy from Steubenville. Dean Martin wasn’t always Dean Martin—he was born Dino Paul Crocetti on June 7, 1917, in Steubenville, Ohio. His father, Gaetano, was a barber; his mother, Angela, was Ohio-born to Italian parents. Dino grew up in an Italian-speaking home and didn’t learn English until age five, which made school difficult and invited bullying. He felt like an outsider and later joked, “I had a bicycle and I never missed a meal, but I was just too smart for those teachers,” masking deeper alienation.

By tenth grade, he’d had enough and dropped out. That decision launched him into a rougher path filled with hard work and risk. He tried following his father into barbering but drifted through jobs—gas station helper, milkman, drugstore clerk. Nothing thrilled him. Boxing did—Dino fought as “Kid Crochet,” winning only one of twelve matches and collecting a broken nose, scarred lip, and shattered knuckles from fighting without wraps.

In New York City, he shared a tiny apartment with fellow striver Sonny King. Money was scarce, so they turned their living room into a bare-knuckle fight club, charging admission until someone got knocked out. Dean even flattened Sonny in the first round of a sanctioned match. Deep down, he knew getting beat up wasn’t a future—he needed a change, even if he didn’t know what it would be.

From smoke-filled rooms to singing on stage. After leaving boxing, Dino landed in a backroom casino behind a tobacco shop—illegal, but paying. He worked as a roulette stickman and blackjack dealer in a haze of smoke and risk. Then something unexpected happened—he sang. Co-workers noticed the smooth, warm charm in his voice, and bandleader Ernie McKay offered him a spot.

Performing as “Dino Martini” (inspired by tenor Nino Martini), he played Ohio nightclubs. In 1938, he joined Sammy Watkins, who took him on tour and gave career-shaping advice: change your name to Dean Martin. He did. By 1943, Dean was in New York performing full-time—hustling for notice, sharpening the persona that would soon make him world famous.

As Dean’s name grew, so did the act. He didn’t just sing; he performed—glass of “whiskey” in hand, loose tie, relaxed grace. The look borrowed from Phil Harris, a showman who sold a hard-drinking persona, but Dean refined it into “king of cool.” Offstage, though, he was quiet and shy. In a 1967 interview with Oriana Fallaci, he admitted people thought he was stuck-up; in truth, lingering language insecurity kept him silent.

On stage, he was confident, playful, and wickedly funny. Offstage, he stayed reserved and unsure, never forgetting where he came from. That tension—tough beginnings and inner struggle—followed him for life. Then came Jerry Lewis.

Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. In August 1944, at the Belmont Plaza Hotel, Dean spotted a young comic named Jerry Lewis and said, “Hey, I saw your act. You’re a funny kid.” They hit it off and formed a duo. Their first show at Atlantic City’s 500 Club on July 24, 1946 bombed; owner Skinny D’Amato threatened to fire them if the next set didn’t land.

They ran to the alley and reimagined the act: Jerry as a chaotic busboy, Dean trying to sing while bread rolls flew and dishes crashed. Audiences erupted. The slapstick chemistry, improv, and anarchic playfulness made them stars—their joy performing for each other invited the crowd in. They conquered the Copa in New York, debuted on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town in 1948, and hired young writers Norman Lear and Ed Simmons to elevate their material.

In 1949, Paramount signed them for My Friend Irma, with comic freedom protected by agent Abbe Gresler—one film a year through York Productions plus control over clubs, records, radio, and TV. The duo earned millions. Jerry later wrote, “Dean was one of the great comic geniuses of all time.” They were close—Jerry was best man at Dean’s 1949 wedding—but cracks were forming.

Leaving Jerry Lewis. Success bred repetition—critics complained the movies felt the same, and Dean grew tired of one-note roles. During Three Ring Circus (1954), Look magazine ran a cover of Jerry and Sheree North—with Dean cut out. Dean exploded at the publicist; the slight burned. He felt sidelined: “Anytime you want to call it quits, just let me know.”

He started showing up late—“Why the hell should I come in on time? There’s nothing for me to do.” In Three Ring Circus, he didn’t sing until 35 minutes in—and it was an old tune to animals. The magic felt one-sided. Dean stayed professional until the contract ended, then walked away on July 25, 1956—ten years to the day after their first show—quietly, with dignity.

Life with the Rat Pack. After the split, Dean soared—singing, acting, and Vegas headlining. He joined the Rat Pack: Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford—late nights, laughter, liquor, and style. Outsiders thought Dean was the wildest of all—Frank joked, “He’s got a tan because he found a bar with a skylight.”

In truth, Dean wasn’t a party animal. He often left early and did things his way. Tom Dreesen, Sinatra’s opener, said Dean’s quiet independence sometimes irritated Frank—then earned his respect. On stage, their bond was electric; Dean’s daughter Deana said you could see the love and respect in their eyes. Their families were close, more like brothers than co-stars—though even strong friendships can be tested.

Mob ties, drinks, and the act behind the man. Dean’s past wasn’t spotless—he bootlegged and fought bare-knuckle, so mob-adjacent crowds didn’t shake him. Frank’s ties to organized crime were deeper; most kept quiet around gangsters. Dean didn’t bend. After one show, mobsters thanked him; he said, “No, I did it for Frank,” and walked away—bold, fearless, unowned.

The drink was part of the act—Sammy joked, “If this don’t straighten my hair, nothing will.” In truth, Dean’s glass often held Martinelli’s apple juice. The slur and sway were showbiz. Backup singer Patti Gribow affirmed it; Jerry Lewis did too. Dean told the Saturday Evening Post he drank about “one-tenth” of what he pretended—craft, not chaos.

The Dean Martin Show. When NBC offered him a variety show in the mid-1960s, Dean said yes—on his terms. He’d only work Sundays, wouldn’t rehearse, and wanted to own the show after one airing. NBC agreed. Dean had a stand-in run full rehearsals with dancers and guests; sometimes, if there wasn’t a football game, he watched from his dressing room monitor. When the red light came on, he was smooth, relaxed, and entirely in control.

The Dean Martin Show ran from 1965 to 1974, drawing 40 million viewers with a natural, effortless vibe. “It ain’t nothing phony,” Dean said. “That’s really me.” Even Elvis admired him—despite friction with Sinatra, Elvis counted Dean among his idols and once sang “Everybody Loves Somebody” with Dean in the audience. Dean loved comic books; the only full book he said he ever read was Black Beauty. “If you have luck, you don’t have to be smart,” he quipped—perfectly on brand.

He stayed a lifelong comics fan, starstruck meeting Batman creator Bob Kane, and even headlined The Adventures of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis—a 40-issue series from 1952 to 1957. Yet the quiet star carried a heavy heart.

A quiet star with a heavy heart. In 1987, tragedy struck—Dean’s son, Dean Paul Martin, died in a jet crash at 35. Dean was shattered. He withdrew, even walking out on a tour with Sinatra; Tom Dreesen said that’s when their distance began. Though they later reconciled, something in Dean was gone. After Dean’s death, Frank said, “Dean has been like the air I breathe,” honoring a brother by choice.

Even with massive success, Dean never chased attention. The Dean Martin Show’s easy charm made him a TV fixture. From 1974 to 1984, he hosted the Celebrity Roasts—stars and politicians skewered in good fun—another hit. He performed constantly—stages, nightclubs, studios. He appeared in 85 films and TV shows, sold over 12 million U.S. records (50 million worldwide), and imprinted America with songs like “That’s Amore,” “Everybody Loves Somebody,” and “Ain’t That a Kick in the Head.”

Dean’s first love and a growing family. In 1941, he married Elizabeth Anne “Betty” MacDonald. They lived in Cleveland Heights and quickly grew their family: Craig (1941), Claudia (1944), Gail (1945), and Deana (1948). After eight years, they divorced in 1949; Dean won custody of all four. Betty moved to San Francisco, stayed private, and passed in 1989. She helped raise the first half of the big family Dean would be known for.

His second wife—24 years by his side. A week after the divorce, Dean married Jeanne Biegger, an Orange Bowl Queen and model, on September 1, 1949; Jerry Lewis was best man. They’d met the previous New Year’s Eve in Miami—Jeanne later said they “locked eyes” and fell madly in love. Together they had Dean Paul (1951), Ricci (1953), and Gina (1956); Jeanne became stepmother to Dean’s four, making seven in all.

Dean joked about the big brood: “I’ve got seven kids—the three words you hear most around my house are ‘Hello, goodbye, and I’m pregnant.’” Their marriage looked glamorous—top singer, actor, Vegas headliner, and Rat Pack star—but it ended. On December 10, 1969, Jeanne announced their separation; the divorce finalized in 1972. Dean filed and later quipped, “I know it’s gentlemanly to let the wife file, but everyone knows I’m no gentleman.”

The shortest marriage and the last wedding. In 1973, Dean married Catherine Hawn, a Beverly Hills salon receptionist, introduced by a family friend. The wedding was star-studded—Frank included—but the marriage lasted only three years, ending in 1976. Dean adopted Catherine’s daughter, Sasha, as his own. He never married again over the final 19 years of his life.

After Catherine, Dean reconnected with Jeanne—not remarried, but closer, especially after their son’s death. The heartbreak drew them together; Jeanne stood by Dean through grief he never fully recovered from. They remained close until his passing in 1995 from complications tied to lung disease.

Affairs, rumors, and one explosive secret. In her memoir, Sandra Lansky—daughter of mob boss Meyer Lansky—claimed an affair with Dean while Jeanne was pregnant with Gina. She wrote vivid accounts, saying they had an unspoken pact to never discuss personal lives and that she didn’t know Jeanne was pregnant. Fans saw Dean as a charming family man; insiders like music director Lee Hale said the “booze and broads” jokes were part of the act. Sandra’s story revealed a more complicated man—brilliant and flawed.

His final years—loss beyond repair. According to author William Keck, Dean’s later years were defined by sorrow more than fame. He told Fox News that Dean’s spark faded; Dean would say, “I’ll be back on that stage one day,” but his heart wasn’t in it. Impressionist Rich Little said, “Once he lost his son, that was the end of him.” Jerry Lewis added, “Dean let himself go”—the old act overtaken by real pain.

Dean withdrew from the spotlight. In 1993, years of heavy smoking caught up—he was diagnosed with lung cancer at Cedars-Sinai. Doctors recommended surgery; he refused. By early 1995, he retired from public life and stayed home in Beverly Hills, far from cameras and crowds. On Christmas Day, he died of acute respiratory failure caused by emphysema at age 78.

Las Vegas dimmed the Strip lights in his honor—a city saluting a legend who helped define it. He was buried at Westwood Village Memorial Park in Los Angeles, beneath a line from his most famous song: “Everybody loves somebody sometime.” At the private funeral, Rosemary Clooney sang “Everybody Loves Somebody.” In a room full of stars, a simple song from a friend said everything—a quiet goodbye to a legend who, in the end, was just a father, a friend, and a man who missed his son.

Do you think Dean Martin found peace in his final years—or did heartbreak linger to the end? Share your thoughts in the comments. Hit like, subscribe, and stay tuned for more captivating stories from Hollywood’s fascinating history. See you next time.

News

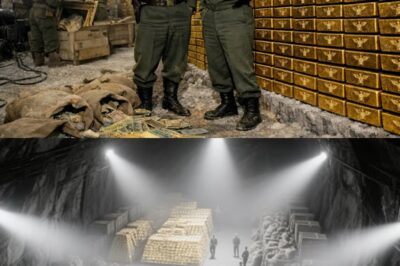

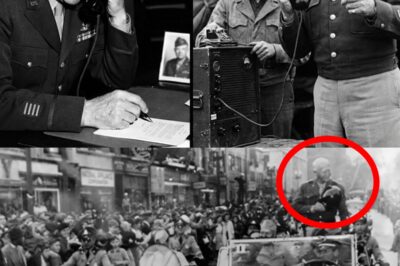

What Patton Found in This German Warehouse Made Him Call Eisenhower Immediately

April 4th, 1945. Merkers, Germany. A column of Third Army vehicles rolled through the shattered streets of another liberated German…

What MacArthur Said When Patton Died…

December 21, 1945. Tokyo, Japan. General Douglas MacArthur sits in his office in the Dai-ichi Seimei Building—the headquarters from which…

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne

If Patton hadn’t moved in time, the 101st Airborne wouldn’t have been captured or forced to surrender. They would have…

The Phone Call That Made Eisenhower CRY – Patton’s 4 Words That Changed Everything

December 16, 1944. If General George S. Patton hadn’t made one phone call—hadn’t spoken four impossible words—the United States might…

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

End of content

No more pages to load