A Fur Bikini Made Her a Myth. A Courtroom Made Her Dangerous.

The photograph was simple: a woman in a prehistoric fur bikini standing against a barren horizon, eyes narrowed, posture unbreakable. It stamped itself onto the 1960s like wet ink, turned Raquel Welch into a global sex symbol, and sold a fantasy that seemed immortal. But the myth missed the other woman—the Chicago-born daughter of a Bolivian aeronautical engineer and an Irish-American mother, powdered by stage lights yet steeled by a conservative upbringing, a straight‑A student built on ballet discipline and pageant poise who would one day march into a Los Angeles courtroom and make a movie studio pay for misjudging her.

This is the story behind the poster. It’s about how a family’s private tensions forged a public spine, how a Latina star refused to be renamed, how Broadway and a business line of wigs outlasted bikini jokes, how a “difficult” label was arguably the cost of demanding control, and how one “temperamental” actress forced the industry to read its own contracts—out loud.

I. Before the Myth: Chicago Birth Certificate, La Jolla Discipline

– Birth name: Jo Raquel Tejada. Born Sept. 5, 1940, Chicago, Illinois.

– Parents: Armando Tejada (Bolivian, aerospace engineer) and Josephine Sarah (Irish-American, well-educated, straight‑laced).

– 1942 move: The family relocates to San Diego (General Dynamics). A small stucco house in La Jolla, two blocks from the beach. Siblings follow: James and Gail.

Inside that house lived a paradox: a passionate, highly emotional father and a mother who believed in restraint. The air crackled. Raquel learned calibration—how to find refuge in precision. Ballet classes replaced chaos with order; movie theaters offered other worlds and alternate endings. Her classmates shortened her name—Rocky—because they couldn’t say Raquel. She studied dance and drama, won “Miss Photogenic,” “Miss Contour,” and “Fairest of the Fair,” and served as vice president of her senior class. She was a star cheerleader with straight A’s and a plan.

Then the barre broke. By 17, her instructor told her she didn’t have the body for a ballet career. So she pivoted—from pliés to lenses.

II. The Weather Girl, the Bus Routes, and the Two Hundred Dollars

– 1959: Marries high‑school sweetheart James Welch.

– 1960: Son, Damon; 1961: Daughter, Tahnee. Studies, family, and a San Diego TV weather job stretch her thin; college falls off the table.

– 1964: Divorce finalized; she keeps “Welch”—practical and protective in a Hollywood wary of overt Latinidad.

She tries Dallas—models for Neiman Marcus, waits tables, dreams of New York. Two hundred dollars says otherwise. She reroutes to California with two kids and a stack of headshots; studios are traversed by bus and foot. She pockets bit parts—A House Is Not a Home, Elvis’s Roustabout—then fate sits next to her in a Sunset Boulevard coffee shop. Publicist Patrick Curtis offers management. A summer teen movie, A Swingin’ Summer (1965), draws Variety’s flashing neon: “It’s hard to look away when she’s in view.” The line becomes a prophecy.

III. “Call Her Debbie” (They Tried): Contracts, Bond Buzz, and Fox Control

Raquel’s screen tests catch 20th Century Fox’s attention. Executives press her to change her name to Debbie. She declines. Meanwhile, James Bond producer “Cubby” Broccoli considers her for the next Bond movie. Fox moves fast—locks her to an exclusive deal before 007 can dial.

1966 brings Fantastic Voyage, a sci‑fi hit with Raquel as a co‑star, and, soon after, a transatlantic “loan” to Hammer Films in the UK for a prehistoric adventure. The loan yields a detonation.

IV. The Day the Poster Started Breathing

One Million Years B.C. (1966) remixes a 1940s caveman fantasy. The story is passable; the image is unforgettable: Raquel Welch as Luana, wearing a revealing doe/fur bikini against a desolate landscape. In an era still haunted by the blonde bombshell archetype (Marilyn, Jayne), Raquel debuts a new silhouette—brunette, athletic, steelier. The poster sells millions; it attaches to dorm walls, barracks, and imaginations. Overnight, Raquel is a global image—“the most photographed woman in the world” through the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Then comes the cage. “Being a sex symbol,” she would say later, “is like being a convict. I was locked in this image and couldn’t get out.” She insists it’s a character. Studios insist it’s the plot.

V. The Range She Wanted vs. The Roles They Wrote

Fox pairs her with marquee men for mainstream credibility:

– Bandolero! (1968): With James Stewart and Dean Martin.

– Lady in Cement (1968): With Frank Sinatra.

– 100 Rifles (1969): With Jim Brown; features one of the first interracial love scenes in a major Hollywood production.

Raquel’s star power keeps swelling; column inches obsess over costumes. She brings presence and humor; the camera asks for skin. The industry message is clear: we’ll bankroll the silhouette, not the interiority.

VI. The Blowtorch: Myra Breckinridge and the “Difficult” Stamp

1970’s Myra Breckinridge—Gore Vidal’s provocation about gender and power—offers Raquel a risky pivot. The production is rocky; the reception, brutal. The film flops. The blame lands on her. The label arrives—“temperamental,” “unprofessional,” “diva”—and sticks. Horror stories multiply: quarreling with directors, insistent demands, tension on set. Many are later contested or contextualized; most are retold as gospel.

In 1985, Barbara Walters asks if she’s difficult. Raquel: “I’m very much a perfectionist and quite demanding. But I’m worth it.” In a town that calls men like this “visionaries,” Welch learns what it costs women to say the same sentence.

VII. Reinvention on Her Terms: Cabaret, Broadway, TV Wins, and Business

With film scripts trying to shrink her back into a bikini, she goes wide:

– TV films: The Legend of Walks Far Woman (shot 1979; aired 1982) is her proudest—an Indigenous lead across decades; followed by Right to Die (1987), Scandal in a Small Town (1988), and Trouble in Paradise.

– Stage: Cabaret act turns to Broadway; she wins the lead in Woman of the Year, proving star wattage doesn’t require a swimsuit.

– Fitness & products: She leans into a public image on her terms—best‑selling exercise tapes and books; later, a successful signature wig line that becomes a durable business.

She stops waiting for studios to decide if she’s allowed to evolve and learns to make the market meet her.

VIII. The Firing That Backfired: Cannery Row and a Landmark Verdict

1981. MGM fires Welch weeks into shooting Cannery Row opposite Nick Nolte, citing a supposed violation of her pay‑or‑play contract ($250,000) because she did hair and makeup at home. She is replaced by 25‑year‑old Debra Winger. Welch offers to accept the recast if MGM guarantees another role; the studio declines.

She sues: $24 million for breach of contract. The arguments crystallize Hollywood’s gendered lexicon:

– MGM: She’s “temperamental,” uncooperative.

– Welch’s attorney Edward Mosk: Arrogant executives discarded a person and a binding contract.

The jury sides with Welch. Damages and punitive awards total $10 million (roughly $20 million today). Seven years later, an appellate court upholds the ruling. Beyond a personal victory, it’s a shot across the studio bow: pay‑or‑play is enforceable; smearing a star to justify a breach won’t hold.

To executives, a bikini is easy to manage. A plaintiff is not.

IX. The Family Script: Why She Kept “Welch,” and What She Hid in Plain Sight

Raquel chose to keep Welch after divorce—a calculation that sheltered her from an era’s ethnic gatekeeping. She pushed back on a “Debbie” rebrand, kept her first name, built a career as an American star while the industry struggled to handle Latina identity outside caricature. It didn’t make her less Latin; it made her more employable. Inside interviews, she credits a conservative mother and a volcanic father for the force field she carried. That field let her perform sexuality without relinquishing the helm.

The “family secret,” if there is one, is that her so‑called “diva” aura was shaped by a household where control was survival, not a quirk. She learned to say no in a room that didn’t always let women say it.

X. What the Poster Covered: Comedienne, Contract Killer (of Bad Deals), and a Career Tactician

Highlights often missed by the myth:

– Golden Globe, Best Actress (Musical/Comedy), The Three Musketeers (1973): validation for comedic craft.

– Interracial intimacy milestone in 100 Rifles: a studio test of boundaries.

– TV dramatic turns: proof she could anchor more than a pose.

– Broadway lead: proof she could hold a house without an action cutaway.

– Entrepreneur: a wig line that transformed image into equity.

The through‑line isn’t a bikini. It’s agency.

XI. Why “Difficult” Becomes a Weapon—and What Her Case Did About It

The anecdotes that fed her “temperamental” reputation lived in the same rhetorical drawer that often penalizes women for precision, boundaries, and self‑advocacy. Raquel’s insistence on more say—a different makeup plan, a contract honored, a name unaltered—collided with an era that expected compliance from women it had already objectified. Her verdict against MGM didn’t erase the label; it made it more expensive to weaponize.

News

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

– Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying German prisoners slowed at Camp Ruston as nineteen women pressed their faces against…

Japanese Kamikaze Pilots Were Shocked by America’s Proximity Fuzes

-April 6, 1945. Off Okinawa in the East China Sea, dawn breaks over Task Force 58 of the U.S. Fifth…

When This B-26 Flew Over Japan’s Carrier Deck — Japanese Couldn’t Fire a Single Shot

At 7:10 a.m. on June 4, 1942, First Lieutenant James Muri dropped to 200 feet above the Pacific, watching thirty…

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home

November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

Why British Carriers Terrified Japanese Pilots More Than the Mighty U.S. Fleet

April 6, 1945. A Japanese Zero screams through the morning sky at 400 mph. The pilot, Lieutenant Kenji Yamamoto, has…

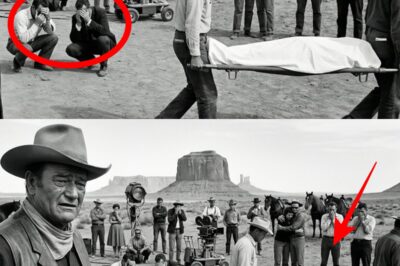

A Stuntman Died on John Wayne’s Set—What the Studio Offered His Widow Was an Insult

October 1966. A stuntman dies on John Wayne’s set. The studio’s offer to his widow is an insult. Wayne hears…

End of content

No more pages to load