October 15, 1950. A lonely airstrip on Wake Island—a coral speck in the Pacific, blistering heat warping the air above the tarmac. A modified DC-6, the Independence, touches down carrying President Harry S. Truman. Waiting is General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, viceroy of Japan and living legend. Protocol demands a salute; MacArthur offers a casual handshake instead.

He stands hands on hips—open-collared shirt, sunglasses, battered “scrambled eggs” cap—more rival emperor than subordinate. Truman smiles for the cameras, the polite politician playing his part. Behind the smile, an artilleryman seethes. He senses the danger of MacArthur’s ego. What he does not yet see is the secret plan already taking shape—one that calls for 34 nuclear bombs.

To grasp the insult, you have to understand 1950. MacArthur had ruled occupied Japan with absolute authority—wrote a constitution, rebuilt an economy, resurrected a nation. For fourteen years, Tokyo was his court; his word was law. Truman, by contrast, was the accidental president—a former haberdasher whose approval ratings were sliding. To the public, MacArthur was a demigod; Truman, merely a man in a suit.

This imbalance fed a toxic delusion. MacArthur believed he answered to God and history, not to a temporary occupant of the White House. He viewed Korea not as a UN police action, but as his personal crusade. Fresh from the brilliant Inchon landing, he assured everyone the war was effectively over—“Home by Christmas.” He dismissed China as too primitive and too afraid of American airpower to intervene.

At Wake Island, Truman asked plainly about Chinese or Soviet interference. MacArthur leaned back, lit his pipe, and said “Very little.” He insisted only 50,000–60,000 Chinese could cross the Yalu and, without air cover, they would be slaughtered before Pyongyang. He was wrong by a factor of six. While he spoke, Marshal Peng Dehuai had already moved 300,000 troops into North Korea—night marches, camouflage, mountain cover, invisible to air reconnaissance.

Major General Charles Willoughby, MacArthur’s intelligence chief—“Sir Charles” for his arrogance—ignored reports of captured Chinese, calling them volunteers. On November 24, MacArthur launched “Home by Christmas,” splitting his forces with a fifty-mile gap between Eighth Army in the west and X Corps in the east. He marched into the jaws of a dragon he insisted didn’t exist. The snap came on November 25.

Temperatures fell to -34°C, freezing gun oil and plasma. Out of the mist, thirty Chinese divisions attacked in human waves. The Eighth Army reeled in the longest retreat in U.S. history—120 miles in ten days, the “Big Bug-Out.” At Chosin Reservoir, 30,000 UN troops faced 120,000 Chinese. Seventeen thousand U.S. casualties, more than 7,000 frostbite cases—feet blackening, weapons jamming, positions overrun at night by trumpets and whistles.

From the Dai-Ichi Building, MacArthur watched his masterpiece collapse and refused responsibility. He claimed Washington had tied his hands and declared this a new war. Then he reached for the ultimate option. On December 9 and again on December 24, he submitted requests for thirty-four atomic bombs. The plan was precise—and apocalyptic.

He proposed dropping thirty to fifty bombs across the neck of Manchuria and laying a belt of cobalt-60 along the Yalu—radioactive for decades, a lethal barrier no living thing could cross. He demanded authority to strike Chinese industry and unleash Chiang Kai-shek from Taiwan. It was not about winning Korea—it was about erasing China. Truman read and understood: the man in Tokyo was no longer a general; he was a threat to civilization.

The breaking point came with a letter. In March 1951, MacArthur wrote to House Minority Leader Joseph Martin, mocking limited war: “There is no substitute for victory.” On April 5, Martin read it on the House floor—a serving general conspiring with the opposition to undercut the commander-in-chief. Truman shut the paper, opened his diary, and wrote: This is the last straw.

At 1:00 a.m. on April 11, 1951, in Blair House, Truman signed the order firing MacArthur—stripping him of all commands: SCAP, CINC UN Command, CINC Far East. A communications glitch delayed the official cable. MacArthur learned his fate from the radio while lunching at the Embassy in Tokyo. Colonel Sid Huff whispered to Mrs. MacArthur; she told him. The god of Tokyo went pale.

In America, the shock was volcanic. The White House switchboard jammed; Truman knew he had committed political suicide. Approval plunged to 22 percent—lower than Nixon in Watergate. Effigies burned; “Impeach” signs sprouted on lawns. MacArthur returned to a hero’s welcome—7.5 million for a ticker-tape parade—and delivered his “Old soldiers never die” speech to Congress. For a moment, he seemed destined for the White House.

Then came the hearings. In May, the Senate convened joint sessions. Omar Bradley and George Marshall testified respectfully—but revealed the nuclear requests and the intelligence failures. Bradley’s sentence finished MacArthur: “Wrong war, wrong place, wrong time, wrong enemy.” The fever broke. The public saw the abyss Truman had avoided. MacArthur faded into the Waldorf, a bitter old man.

Truman left office in 1953, widely considered a failure, returning to Independence with his own suitcases and no pension. History corrected the record. Firing MacArthur was among the bravest decisions a president ever made—an act to preserve civilian control of the military. Truman accepted the hatred of his era to secure the future of the republic.

The day MacArthur refused to salute, the conflict began. The day Truman fired him, the system worked. In the end, the hat salesman proved stronger than the Caesar. He taught a lesson that still echoes in the nuclear age: the power to destroy the world must never rest in the hands of a man who believes he is a god.

News

Why Patton Was the Only General Who Predicted the German Attack

– December 9, 1944. A cold Monday morning at Third Army headquarters in Nancy, France. Colonel Oscar Koch stood before…

What German High Command Said When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

– “Impossible. Unmöglich.” That word echoed through German High Command on December 19, 1944. American General George S. Patton had…

Patton (1970) – 20 SHOCKING Facts They Never Wanted You to Know!

– Behind the Academy Award-winning classic Patton lies a battlefield of secrets. What seemed like a straightforward war epic is…

George S. Patton’s Victories Don’t Excuse What He Did

When disturbing allegations about George S. Patton surfaced, his daughter fiercely defended him. Only after her death did her writings…

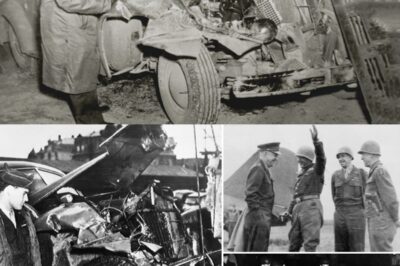

Was General Patton Silenced? The Death That Still Haunts WWII

Was General Patton MURDERED? Mystery over US war hero’s death in hospital 12 days after he was paralyzed in an…

Patton’s Assassin Confessed – He Was Paid $10,000

September 25, 1979, Washington, D.C. The Grand Ballroom of the Hilton sat in shadow—450 living ghosts at round tables under…

End of content

No more pages to load