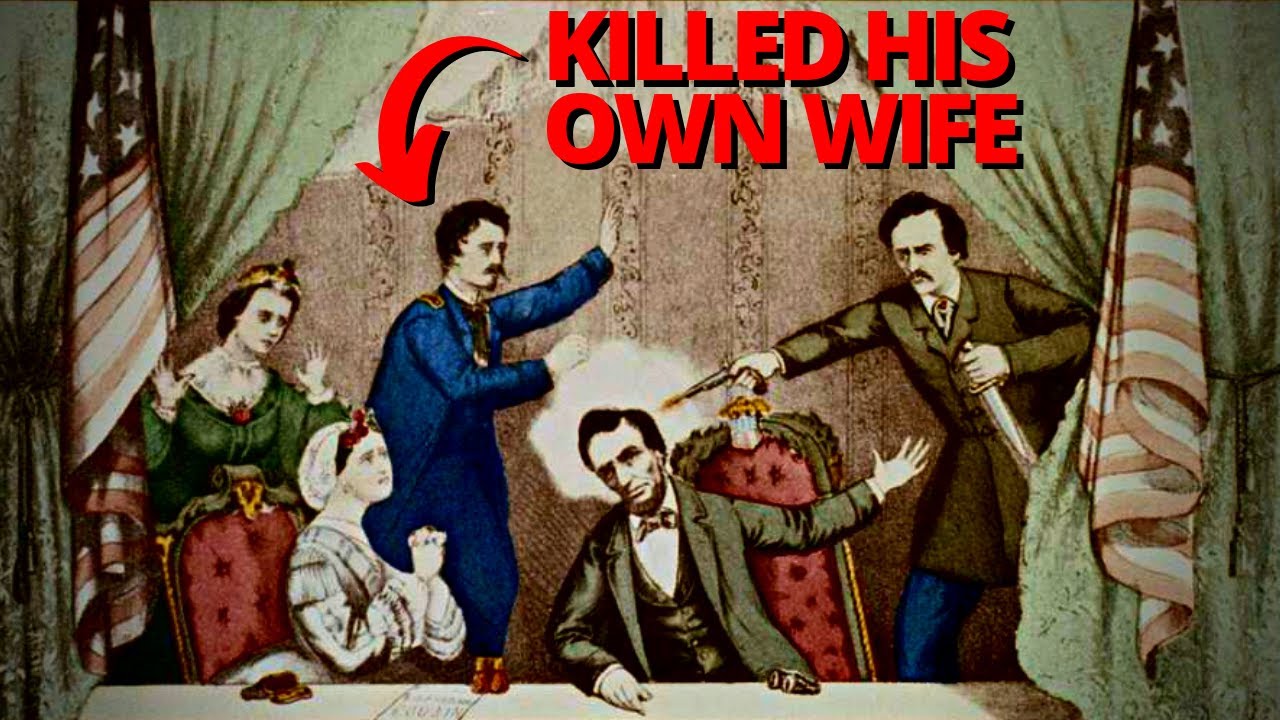

April 14th, 1865.

The story begins with an invitation from President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary to attend a performance at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. It was the evening of April 14th, just days after the Confederacy’s collapse. Lincoln first invited General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife Julia, as well as several others, but they declined.

So Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, were asked to join the presidential couple instead. That seemingly simple decision would change the rest of Rathbone’s life.

At 10:14 p.m., during the climax of the comedy “Our American Cousin,” someone could be heard entering the presidential box. Moments later, a deafening gunshot shattered the laughter in the theater.

Frightened screams filled the air as people realized what had happened: the president had been shot in the back of the head. The attacker was none other than the famed actor John Wilkes Booth.

Rathbone leaped from his chair and rushed to stop Booth. As he grappled with him, Booth slashed Rathbone badly with a dagger. Rathbone later said the look of rage on Booth’s face terrified him.

Even wounded, Rathbone grabbed Booth again as the assassin climbed onto the balustrade of the box. He seized Booth’s coat, but Booth wrenched free and leapt. He fell awkwardly to the stage below, possibly breaking his leg, yet still managed to rise and flee.

Despite the injury, Booth remained at large for the next 12 days, triggering one of the most intense manhunts in American history.

Rathbone, bleeding heavily, helped escort Mary Lincoln from the theater. The mortally wounded president was carried across the street to a boarding house—now known as the Petersen House. Rathbone accompanied the First Lady there.

Despite his terrible wound, Rathbone initially tried to downplay his condition. He soon lost consciousness from blood loss. Clara arrived at the Petersen House shortly afterward. She held her fiancé’s head in her lap as he drifted in and out of awareness.

The surgeon attending Lincoln focused entirely on the dying president at first. Only later, when he finally examined Rathbone, did they realize how serious his injuries were.

Booth’s dagger had nearly severed an artery and sliced to the bone. Yet in the chaos of history’s most infamous assassination, his wound had gone largely unnoticed.

Rathbone was eventually escorted home, while Clara stayed with Mary Lincoln through the night. She remained at the First Lady’s side for eight agonizing hours, until the president died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15th, 1865.

### Henry Rathbone’s Background

Before we follow his tragic decline, it helps to understand who Henry Rathbone was before that night.

Henry Reed Rathbone was born in Albany, New York, into a prominent and wealthy family. His father, Jared L. Rathbone, was an influential merchant and businessman who eventually became the first elected mayor of Albany.

When Henry’s father died, Henry inherited $200,000—a fortune at the time, roughly equivalent to around six million dollars today. Four years later, his widowed mother married Ira Harris, a respected lawyer and widower with four children of his own.

Ira Harris was also a significant figure in national politics. After William H. Seward became Lincoln’s Secretary of State, Harris was appointed United States Senator from New York. That marriage made Harris Henry’s stepfather and brought the families together under one roof.

Among Ira Harris’s children was his daughter Clara. She became Henry’s stepsister—and, eventually, the love of his life.

Clara Harris and Henry developed a close friendship as they grew up together in this blended, influential household. Their relationship deepened from companionship into romance, and just before the American Civil War, they became engaged.

Rathbone studied law at Union College and later worked in an Albany law firm. He was not known for strict discipline in his studies and gained a reputation for missing lectures, but he had the connections and background to build a respectable career.

His life took a different direction when he joined the New York National Guard in 1858. He served as a judge advocate, combining his legal training with military duty. Soon afterward, he was chosen to serve as an observer in Europe during the Second Italian War of Independence, gaining early exposure to conflict and international affairs.

When the American Civil War began, Henry joined the Union Army. He served as a captain in the 12th U.S. Infantry Regiment.

Rathbone saw action at major battles, including Antietam and Fredericksburg—both bloody and traumatic engagements. These experiences alone could have left lasting psychological scars, even without what he would later witness in Ford’s Theatre.

In the years after the war, his physical wound from Booth’s dagger eventually healed. But his mind did not.

### The Downward Spiral

Although he had survived the attack at Ford’s Theatre, Henry Rathbone never truly escaped that night. The assassination haunted him.

On July 11th, 1867, he married Clara Harris. The couple seemed, from the outside, to be stepping into a promising future. They had three children together. Henry continued his military career and rose to the rank of brevet colonel.

But beneath the surface, he was deteriorating.

Rathbone resigned from the army in 1870. After leaving military service, he struggled to find and keep steady work. His mental state was fragile and increasingly unstable, interfering with any attempt at a normal professional life.

The night of Lincoln’s assassination replayed endlessly in his mind. The sound of the gunshot, the flash of Booth’s rage, his own wound, his failure to stop the assassin—these memories clung to him like shadows.

Every year, around the anniversary of Lincoln’s death, his torment grew worse. Journalists and curious visitors sought him out, eager for a firsthand account. Each interview forced him to relive the horror.

Afterward, he tried to numb himself. He turned to drinking, then to gambling. Those habits only intensified his sense of failure. He felt increasingly inadequate—not only as a soldier, but as a husband and father.

As his mental state declined, his relationship with Clara became strained and fearful.

Henry grew paranoid and jealous. He convinced himself that Clara was being unfaithful, despite little to no evidence. He resented the attention she gave to their children, interpreting maternal care as emotional betrayal.

He became convinced that she would leave him, take the children, and abandon him. These beliefs fed a cycle of anger, suspicion, and emotional volatility.

Clara, however, understood at least part of his torment. In a letter to a friend, she described the emotional burden of their shared past:

“In every hotel we’re in, as soon as people get wind of our presence, we feel ourselves becoming objects of morbid scrutiny.”

She added, “Henry imagines that the whispering is more malicious than it can possibly be.”

To Clara, the staring and whispering were uncomfortable but bearable. To Henry, they were suffocating.

By modern standards, many historians and medical experts believe that Henry Rathbone suffered from severe post‑traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and possibly schizophrenia. His intrusive memories, paranoia, and deteriorating grip on reality fit patterns we recognize today.

But in the nineteenth century, there were no effective mental health treatments for conditions like his. There was no therapy, no concept of trauma counseling, no medication that could quiet the intrusive thoughts that tormented him.

Year after year, his illness deepened, untreated and misunderstood.

### A Move to Germany – and a Final Breaking Point

In 1882, Henry was appointed U.S. Consul in Hanover, Germany. The family moved overseas—Henry, Clara, and their children.

On paper, it seemed like a new beginning. A post abroad offered status, stability, and distance from the morbid fascination in America with “the couple who were with Lincoln.”

Perhaps Clara hoped that a new environment, far from the whispers and the anniversaries, would calm her husband’s mind. Maybe Germany would be a place where they were not constantly viewed through the lens of that single terrible night.

But geography could not erase his memories—or his illness.

On December 23rd, 1883, two days before Christmas, Henry’s condition reached its breaking point.

Early that morning, in their home in Hanover, he turned on his children. Details are fragmented, but it is believed he became violent, possibly in a paranoid episode. Clara intervened, trying to distract him, to draw his focus away from the children and protect them.

In the chaos that followed, Henry shot Clara multiple times. He then stabbed her and, in a frenzy, turned the knife on himself, plunging it into his own chest five times in an attempt to end his life.

Clara died from her injuries.

Henry survived.

The revelation that Henry Rathbone—the man who had tried to stop Lincoln’s assassin—had himself become a killer sent shockwaves across both Europe and America.

Newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic carried the story. The hero of Ford’s Theatre had turned into a murderer in a fit of madness.

In the aftermath, authorities did not treat him like a typical criminal. It was clear that his actions were driven by insanity, not cold‑blooded calculation. He was declared mentally unfit and committed to an asylum in Hildesheim, Germany.

There, in a locked institution far from the country whose president he once tried to protect, Henry Rathbone spent the remaining 27 years of his life.

He died in August 1911 at the age of 74. He was buried in a city cemetery in Hanover, laid to rest beside Clara—the woman who had sat with Mary Lincoln as Abraham Lincoln breathed his last, and who had tried for years to live alongside a man haunted by that night.

Looking back, Henry Rathbone’s story is more than a footnote to Lincoln’s assassination. It is a portrait of what happens when unimaginable trauma collides with a world that does not understand mental illness.

He was once a promising young officer, wealthy, connected, and engaged to a woman he loved. In an instant, he became forever linked to an event that would haunt him and define him. Without help, without treatment, without any framework to name what he was experiencing, his mind slowly collapsed under the weight of guilt, paranoia, and memory.

His life became a second tragedy born from the first—a reminder that those who survive history’s darkest moments often carry invisible wounds the rest of their days.

And sometimes, the world sees only the moment they break, not the long years of suffering that led there.

News

The US Army’s Tanks Were Dying Without Fuel — So a Mechanic Built a Lifeline Truck

In the chaotic symphony of war, there is one sound that terrifies a tanker more than the whistle of an…

The US Army Couldn’t Detect the Mines — So a Mechanic Turned a Jeep into a Mine Finder

It didn’t start with a roar. It wasn’t the grinding screech of Tiger tank treads. And it wasn’t the terrifying…

Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her : “He Took a Bullet for Me!”

August 21st, 1945. A dirt track carved through the dense jungle of Luzon, Philippines. The war is over. The emperor…

The US Army Had No Locomotives in the Pacific in 1944 — So They Built The Railway Jeep

Picture this. It is 1944. You are deep in the steaming, suffocating jungles of Burma. The air is so thick…

Disabled German POWs Couldn’t Believe How Americans Treated Them

Fort Sam Houston, Texas. August 1943. The hospital train arrived at dawn, brakes screaming against steel, steam rising from the…

**“The Softest Secret of De Gaulle: The Disabled Daughter Who Changed a National Hero”**

Instead of hiding his daughter with Down syndrome, Charles de Gaulle raised her proudly, and she became the heart of…

End of content

No more pages to load