Cleveland, Ohio. Early 1970s.

The factories were slowing down. The promise of the American dream felt like it had a hole in it. Neighborhoods were split by highways, by race, by money—and by the simple fact that some people had doors that locked and heat that stayed on, and others… didn’t.

In one of those working‑class neighborhoods where sirens were common and paychecks were not, a little girl watched everything.

Her name was Tracy Chapman.

She grew up in an apartment where arguments from the street floated in through thin walls, where racial tensions simmered, where poverty wasn’t a concept but a daily reality.

Her parents divorced when she was four.

After that, it was just her mother and two girls against the world.

A mother, a ukulele, and a bill that couldn’t be paid

Tracy’s mother worked every job she could find. Low‑paying, exhausting, often thankless.

Some weeks, it was just enough. Some weeks, it wasn’t.

Sometimes the electricity went out.

Sometimes the gas was shut off, and the house turned into a refrigerator in winter.

Sometimes dinner was smaller than it should have been.

Tracy remembers lining up with her mother to get food stamps—standing in those long lines where time moves slowly and shame moves fast. Where grown adults avoid each other’s eyes because everyone knows why they’re there.

But Tracy’s mother understood something profound: if she couldn’t always give her daughters comfort, she could give them possibility.

When Tracy was three, her mother did something that didn’t make sense on paper:

She bought her a ukulele.

It was a ridiculous extravagance for a woman who sometimes struggled to keep the lights on.

It made no financial sense.

But emotionally, spiritually, it made all the sense in the world.

Music, her mother knew, could be a lifeline that didn’t get cut off when the bill was overdue.

So there was this tiny girl, in a Cleveland apartment with an unstable future, holding a small instrument that cost more than it should have… and less than it would eventually give back.

A self‑taught girl with a notebook full of truth

By the time most kids are just figuring out basic chords in music class, Tracy had already made music her second language.

At eight, she picked up a guitar. No expensive lessons. No fancy teachers. Just her, the instrument, and sheer stubborn determination.

She taught herself to play.

She listened.

She practiced until her fingers hurt.

And she started writing.

Tracy didn’t grow up shielded. She saw violence. She saw struggle. She saw people working two and three jobs and still not making it. She heard the way people talked when they thought children weren’t listening.

She *was* listening.

And she wrote it all down.

At fourteen, while most kids are worried about fitting in at school dances, Tracy was composing her first song of social commentary. Not a love song. Not a bubblegum pop tune.

A song about what she had seen.

About injustice.

About the way poverty twists people’s choices and breaks their backs.

Her music wasn’t escape. It was testimony.

A door opens: “A Better Chance” and a whole different world

Cleveland was all she knew—until a program called A Better Chance opened a crack in the wall.

The program was designed to identify gifted minority students and place them in prep schools—those polished, private institutions where the children of the upper‑middle class and the wealthy prepared for the futures that were essentially handed to them.

At sixteen, Tracy earned one of those scholarships.

She left the familiar chaos of Cleveland for the manicured lawns of the Wooster School in Connecticut.

It might as well have been a different planet.

Her new classmates had grown up with skiing vacations, summer camps, and houses with spare rooms. Some had never met anyone who’d grown up truly poor.

They were curious—but not always kind.

They asked questions that were meant to be conversations, but felt like interrogations.

Questions that revealed their ignorance more than their interest:

“What was it like to be poor?”

“Did you see a lot of crime?”

“Was it scary where you lived?”

To them, her background was exotic. To her, it was just life.

The contrast was brutal. In Cleveland, money had been scarce, but experience was rich and raw. At Wooster, material comfort was abundant, but the reality she knew felt invisible, dismissed, or misunderstood.

Tracy could have shrunk under that gaze.

Instead, she did what she had always done.

She played.

She kept her guitar close.

She turned discomfort into lyrics.

She turned alienation into fuel.

Being an outsider gave her a clearer view of both worlds—the one she’d come from, and the one she was now being allowed to observe up close.

It sharpened her senses. It gave her more to say.

Harvard Square, subway tunnels, and a quiet storm of a voice

After high school, Tracy earned a scholarship to Tufts University in Massachusetts. She chose anthropology as her major—a discipline built on observing humans and their societies.

It was a perfect academic mirror of what she had been doing her whole life: watching people, listening to them, and trying to make sense of how systems shape lives.

But the real stage for her transformation wasn’t a lecture hall.

It was outside.

She busked in Harvard Square.

She played on subway platforms.

She sang in coffeehouses with bad lighting and mismatched chairs, where the air smelled like espresso and anxiety.

Her performances were simple: her voice, her guitar, her songs. No drum machines, no synthesizers, no dancers, no pyrotechnics.

Just words and chords.

Students and strangers stopped. Some stayed. Some cried.

There was something in her voice—steady, unforced, calm but intense—that cut through noise in a way screaming never could.

One night, a fellow student named Brian Koppelman walked into a coffeehouse and heard her.

He froze.

There are moments when you hear something and know instantly: this is not normal. This is not background. This is not just another person with a guitar.

Brian was the son of a music publisher. He understood, maybe better than most students, what he was hearing. He approached Tracy and told her he wanted to introduce her to his father.

Tracy was skeptical.

Industry people had never been part of her world.

Trusting them didn’t come naturally.

But slowly, through persistence and luck, the connection led somewhere very real.

Elektra Records came calling.

The girl who had once stood in line for food stamps with her mother was now signing a record deal.

1988: An album, a voice, and a world on the brink

In April 1988, Tracy released her self‑titled debut album: *Tracy Chapman*.

At a time when Top 40 was dominated by big hair, big drums, glossy production, and huge personalities, her record sounded almost shockingly bare.

No glitter.

No elaborate beats.

Just her voice, her guitar, and songs like “Fast Car,” “Talkin’ ’bout a Revolution,” and “Baby Can I Hold You”—small in arrangement, enormous in impact.

She sang about poverty without pity.

She sang about escape without promising miracles.

She sang about revolution in a voice that sounded more like a quiet prophecy than a war cry.

The album got attention. The critics noticed. Sales were decent—around 250,000 copies. A respectable showing for a relatively unknown, acoustic, politically charged artist.

But the world hadn’t quite caught up yet.

And then, history reached out and grabbed her.

Wembley Stadium. A missing hard disk. A once‑in‑a‑lifetime opening.

June 11, 1988. Wembley Stadium, London.

The occasion: The Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute.

Mandela was still imprisoned. Apartheid still in place. The concert was framed as a call for his freedom—a global broadcast of protest and hope.

Over 70,000 people filled the stadium. Many more watched on screens, in bars, in living rooms. An estimated 600 million viewers tuned in worldwide.

Tracy was on the bill—but not as a headliner.

She played an afternoon set, earlier in the day, far from the prime‑time spotlight. She did what she always did: stepped to the mic, played her songs, poured herself out, and then walked off.

Later, she was backstage, one artist among many. The big names—like Stevie Wonder—were slated to take the stage in the evening, during the peak broadcast hours.

Then chaos hit.

Just before Stevie Wonder’s set, someone realized that the hard disk containing all 25 minutes of his synthesized backing tracks was missing.

Gone.

Without that disk, his entire show could not go on as planned. In front of tens of thousands in the stadium and hundreds of millions watching at home, Stevie—one of the greatest performers alive—was forced to walk off stage in tears.

The organizers panicked.

They had a live global broadcast. Cameras rolling. A massive audience. And suddenly… nothing on stage.

They needed someone who could perform *right now*.

Someone who didn’t need elaborate equipment.

Someone who could hold a stadium’s attention with almost nothing.

There was a woman backstage with an acoustic guitar.

Tracy Chapman.

They asked her to go back out.

One woman. One guitar. Seventy thousand people go quiet.

Imagine it:

You are a relatively new artist. Your debut album has been out for two months. You’ve just played your scheduled set. Now, out of nowhere, people are telling you:

“We need you to walk onto this gigantic stage, in front of this enormous crowd, with almost no warning, and fill the space that was supposed to belong to Stevie Wonder.”

Most people would have frozen.

Tracy didn’t.

She walked out, guitar in hand, into the wash of stadium lights.

No band behind her.

No backup singers.

No screen visuals.

Just her.

She started to play.

She played three songs. One of them was “Fast Car”—a song about a girl trying to outrun generational poverty, trying to drive past the limits geography and class had placed around her life.

In that moment—her voice threading its way through the air, her fingers steady on the strings—something rare happened:

A stadium went quiet to hear a folk song.

No spectacle.

No fireworks.

Just a story held up to the light.

On TV screens across the planet, people who had never heard her before leaned in.

Who is that?

What is this song?

It was one of those moments you cannot manufacture: an unscripted collision of timing, talent, and trouble.

Twenty‑five minutes of chaos. A lifetime of change.

In the two weeks after that unscheduled Wembley performance, everything changed.

Album sales for *Tracy Chapman* jumped from 250,000 to over two million copies.

“Fast Car” shot up the Billboard Hot 100, reaching number six.

The album itself climbed to number one.

Her songs were suddenly everywhere—on radio, in stores, in dorm rooms, in apartments where people sat on the floor and let the lyrics wash over them.

She was no longer just the student busker from Harvard Square or the promising new artist critics liked.

She was a phenomenon.

*Tracy Chapman* would eventually sell over 20 million copies worldwide. The following year, she won three Grammy Awards, including Best New Artist and Best Contemporary Folk Album.

The girl whose mother had once gambled on a ukulele in Cleveland was now a global voice of conscience.

And then, at the height of a level of fame many artists never even approach, Tracy Chapman did something that confounded the industry.

She refused to become a product.

The choice to step back when the spotlight is brightest

After her debut, Tracy continued to release music. Seven more albums followed over the years. Her 1995 single “Give Me One Reason” became another major hit—bluesy, soulful, and unmistakably her. It earned her a fourth Grammy.

But she never tried to become a celebrity in the traditional sense.

No scandal‑courting.

No desperate reinventions to chase trends.

No tabloid headlines.

She rarely did interviews. She didn’t flood the market with appearances. She toured, released, and then receded back into a relatively private life.

By 2008, she released her last studio album. After that: silence.

No new albums.

Very few performances.

In an era when social media was teaching artists to stay constantly visible, constantly “on,” Tracy did the opposite.

She disappeared, at least from the public’s daily line of sight.

To some, it looked like she’d walked away from music.

To others, it looked like an act of self‑respect.

She had said what she needed to say. She didn’t need to keep shouting just to stay seen.

Her songs, especially “Fast Car,” stayed alive on their own—through old CDs, playlists, late‑night drives, and teenagers discovering her decades after her debut.

And somewhere, in North Carolina, a little boy was listening.

A four‑year‑old in the backseat, a song on the radio

Luke Combs grew up far from Cleveland and far from Harvard Square. Born in North Carolina in 1990, he grew into one of the most popular country singers of his generation—known for his big, heartfelt voice and working‑class storytelling.

But long before the fame, there was just a kid in a car seat.

He has said that he fell in love with “Fast Car” when he was around four years old, listening to it with his dad. The song stayed with him—not as a “classic folk track” or an “important piece of social commentary,” but as something raw and honest that cut through.

Decades later, Luke had his own platform, his own fans, his own chart‑topping career.

And he chose to go back to that song.

In March 2023, Luke Combs released a cover of “Fast Car.”

He didn’t change the story.

He didn’t flip the pronouns to make it more conventionally “masculine.”

He didn’t reframe the song through his own ego.

He just sang it—Tracy’s lyrics, Tracy’s melody—through his voice, with reverence.

You could hear the respect in the way he stayed out of the way of the song.

The response was immediate and massive.

A second life for “Fast Car”—and a series of firsts for Tracy Chapman

Luke’s version of “Fast Car” shot up the charts. Country radio picked it up and played it heavily. A song written by a Black woman from Cleveland in the 1980s was now being sung by a white male country star in the 2020s—and somehow, it fit.

The core of the song—wanting a way out, wanting a better life, wanting a chance—was as universal in 2023 as it had been in 1988.

But something else happened too:

On the Billboard Country Airplay chart, Luke’s “Fast Car” hit number one.

That meant that Tracy Chapman—who had not been in the studio, who had not done the promotional rounds, who had not chased a hit—had just become the first Black woman with a *sole songwriting credit* on a number‑one country song.

Not the first Black woman to *sing* on a country track.

The first to have written, alone, the song at the top.

In November 2023, the Country Music Association gave “Fast Car” its Song of the Year award.

In fifty‑seven years of the CMA Awards, no Black songwriter—male or female—had ever won that category.

Tracy Chapman became the first.

She did not attend.

She sent a written statement instead:

“I’m sorry I couldn’t join you all tonight. It’s truly an honor for my song to be newly recognized after 35 years of its debut.”

Thirty‑five years.

A lifetime in the music industry.

And yet, here the song was again. Alive. Relevant. Leading.

It felt like the world had finally gotten around to fully appreciating something that had been quietly brilliant all along.

But the true full‑circle moment was still ahead.

The Grammys, 2024: a riff, a roar, and a standing ovation

February 2024. The Grammy Awards.

Most performances at the Grammys are about spectacle—outfits, choreography, staging. Big moments designed to light up social media feeds.

Amid all of that, a simple stage was set.

Luke Combs was there. So was Tracy Chapman.

When she walked out with a guitar, the audience reacted like they were seeing a once‑in‑a‑generation comet. Because they were. This was an artist who had spent decades refusing the spotlight, now stepping into it by choice.

She began to play the opening riff of “Fast Car.”

Just those first notes.

Simple. Recognizable. Devastating.

The camera panned over the audience. Taylor Swift stood up, singing along, eyes shining. Artists across genres—pop, R&B, rock, country—were on their feet.

Tracy sang the first verse. Her voice was older, but the same. Calm. Steady. Unforced. The kind of voice that sounds like it carries not just lyrics, but lived experience.

Luke joined in.

They didn’t compete.

They shared.

Two artists, from different genres, generations, and racial backgrounds, met in the center of a song written decades earlier by a young Black woman in Cleveland who had simply decided to tell the truth.

At the end, Tracy and Luke turned to each other and bowed.

Within hours, “Fast Car”—the original—hit number one on iTunes.

Thirty‑five years after its release, the world pressed play all over again.

A quiet revolution in plain sight

Tracy Chapman never wanted to be a celebrity.

She never built a “brand.” Never chased a narrative. Never curated an image beyond being exactly who she was.

She came from hunger, instability, and the kind of everyday racism that doesn’t always make headlines but leaves long bruises.

She watched.

She listened.

She wrote.

When she sang about wanting to “get us outta here,” she wasn’t inventing drama.

She was describing reality.

Her music was never about making people feel comfortable. It was about making them feel *seen*—the ones who work dead‑end jobs, who watch their parents count coins, who dream of a car, a bus ticket, a chance.

For years, the industry treated that kind of honesty as niche.

But time has a way of sorting the noise from the signal.

Songs built on trends fade.

Songs built on truth wait.

Sometimes, they have to wait 35 years.

What Tracy Chapman proved without ever trying to

In a world obsessed with speed—overnight virality, constant content, trending sounds—Tracy Chapman’s story moves at a different pace.

She didn’t become famous because of a marketing campaign.

She didn’t remain relevant because she stayed in the headlines.

Her life traces a different kind of arc:

– A little girl standing in line for food stamps with her mother

– A teenager writing protest songs in a poor Cleveland neighborhood

– A scholarship student navigating prep school culture shock

– A college busker playing in subway tunnels

– A young woman walking onto the world’s stage because a hard disk went missing

– A respected artist choosing privacy over fame

– A songwriter quietly making history in a genre that once barely acknowledged her existence

Tracy Chapman didn’t force the world to listen.

She just kept telling the truth.

Eventually, the world turned down the volume on everything else long enough to hear her.

Some revolutions arrive with marching bands and flag‑waving and speeches.

Others slip in through headphones and car radios and late‑night streaming sessions, carried by a voice that sounds like yours, singing about wanting a life that doesn’t hurt so much.

Tracy’s revolution was that second kind.

Soft.

Steady.

Uncompromising.

She showed that you don’t have to shout to be heard across decades.

You just have to say something real—and keep saying it, whether anyone claps or not.

Thirty‑five years after she first sang “Fast Car” to the world, a stadium, a genre, and a new generation finally stood up.

They were late.

She was ready.

News

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Boot Lace Trick” Took Down 64 Germans in 3 Days

October 1944, deep in the shattered forests of western Germany, the rain never seemed to stop. The mud clung to…

Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open

17th April 1945. A muddy roadside near Heilbronn, Germany. Nineteen‑year‑old Luftwaffe helper Anna Schaefer is captured alone. Her uniform is…

“Never Seen Such Men” – Japanese Women Under Occupation COULDN’T Resist Staring at American Soldiers

For years, Japanese women had been told only one thing about the enemy. That American soldiers were merciless. That surrender…

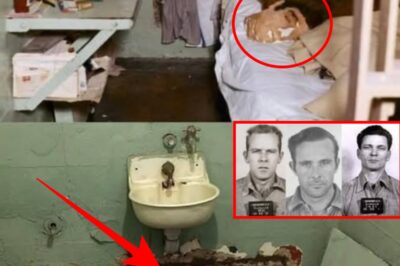

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

End of content

No more pages to load