In 1907, New York City did something unthinkable.

It quietly killed New Year’s Eve.

No countdown, no midnight explosions, no sky on fire.

The city outlawed fireworks, slammed the door on the one spectacle millions lived for, and left party planners staring at a problem that felt almost sacrilegious:

**How do you celebrate the New Year in the world’s loudest city when the law suddenly demands silence?**

The answer did *not* come from a party planner, a politician, or a showman.

It came from the quiet world of maritime navigation, a 700‑pound iron and wood sphere, and a newspaper publisher who refused to let the city’s biggest night go dark.

That night, December 31, 1907, on top of a building that didn’t even exist a decade before, a strange glowing ball slowly began to fall.

The crowd roared.

The clock struck twelve.

And a brand‑new ritual was born—one that would outlive the fireworks, outlive the man who dreamed it up, and eventually be watched by more than a **billion people** around the world.

But none of it was guaranteed.

It all hinged on a ban, a borrowed idea from sailors, and one young metalworker climbing into history with a wrench and a blueprint.

A City That Lived for Noise — and Then Lost Its Spark

At the dawn of the 1900s, **New York City** was already what the rest of the world imagined when they thought of modern life:

– Streets crowded with trolleys and carriages.

– Elevated trains rattling overhead.

– Electric lights cutting through the dusk like magic.

– Cafés, saloons, and “lobster palaces” packed with people who refused to sleep.

New Year’s Eve was not just another holiday.

In New York, it was a **statement**: this city would meet the future with sound and fury.

For years, the sky over Manhattan had answered that call with **fireworks**:

– Explosions tearing the darkness open.

– Smoke drifting over the avenues.

– Strangers kissing, shouting, throwing themselves into the chaos.

But by **1907**, city officials had had enough.

# Fireworks, Fear, and a Police Problem

Fireworks weren’t charming anymore—not to the people in charge.

They were:

– Dangerous.

– Unpredictable.

– A nightmare for fire departments and police.

The city worried about:

– Fires started on rooftops.

– Crowds pushing into unsafe spaces.

– Injuries, chaos, and complaints from business owners.

So in 1907, the decision was made:

**New York City outlawed fireworks within city limits.**

Just like that, the most spectacular moment of the year vanished from the legal calendar.

Those planning public celebrations were left with:

– No crackling sky.

– No legal explosions.

– And a very uncomfortable question: **How do you dazzle a city that expects to be dazzled?**

One man took that question personally.

Adolph Ochs: The Publisher Who Refused to Be Boring

**Adolph Ochs** was not a politician.

He wasn’t a city official, or a Broadway producer, or a millionaire showman in a fur coat.

He was something much more dangerous: a **newspaper publisher** with a flair for spectacle and a deep understanding of what the public craved.

As the publisher of **The New York Times**, Ochs had already transformed:

– The paper’s reputation.

– Its headquarters.

– Its role in the city’s identity.

He wasn’t interested in playing small.

And he was *certainly* not interested in letting New Year’s Eve go quietly.

# Times Square Before the Ball

Back then, the area we now call **Times Square** had only recently earned its name.

– It was known as Longacre Square until 1904.

– That year, The New York Times moved into a new building at the triangular intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue.

– The city renamed the area **Times Square** in honor of the paper.

Ochs didn’t just want an office.

He wanted **a stage**.

He began hosting celebrations around the building—part journalism, part theater, part civic pride.

New Year’s Eve became one of his favorite opportunities.

But with fireworks banned in 1907, his usual plans went up in smoke.

He needed something:

– Big, but legal.

– Silent, but dramatic.

– Visible from blocks away, but controllable.

So he did what great innovators always do:

He looked outside his own world for a solution.

The Sea’s Quiet Secret: The Time Ball

Far from the noise of Manhattan, out on the open sea, sailors lived and died by **precision time**.

Their navigation depended on wristwatches, pocket watches, and ship chronometers being **exact**.

If a ship’s clock was off by even a little, its position on the globe could be dangerously wrong.

So port cities around the world created a solution long before digital time signals existed:

**The time ball.**

# How the Time Ball Worked

The concept was simple but ingenious:

– A large ball was hoisted up a mast or tower in a harbor.

– At precisely noon, the ball would **drop**.

– Ships watching from the water would correct their clocks the moment they saw the ball begin its fall.

No explosion.

No sound needed.

Just gravity, visibility, and strict timing.

It was:

– Quiet.

– Reliable.

– Practical.

To sailors, the dropping ball meant:

**“Your time is now correct.”**

To Adolph Ochs, reading about such devices, it meant something else:

**“Your time is up.”**

A perfect visual metaphor for the last seconds of the year.

The Birth of the Ball: Iron, Wood, and 100 Light Bulbs

Ochs took the old maritime time ball and asked a dangerous question:

What if we **turned it into a show**?

A time ball didn’t explode.

It didn’t make noise.

But in a city that now had to celebrate silently, its simplicity became a feature, not a flaw.

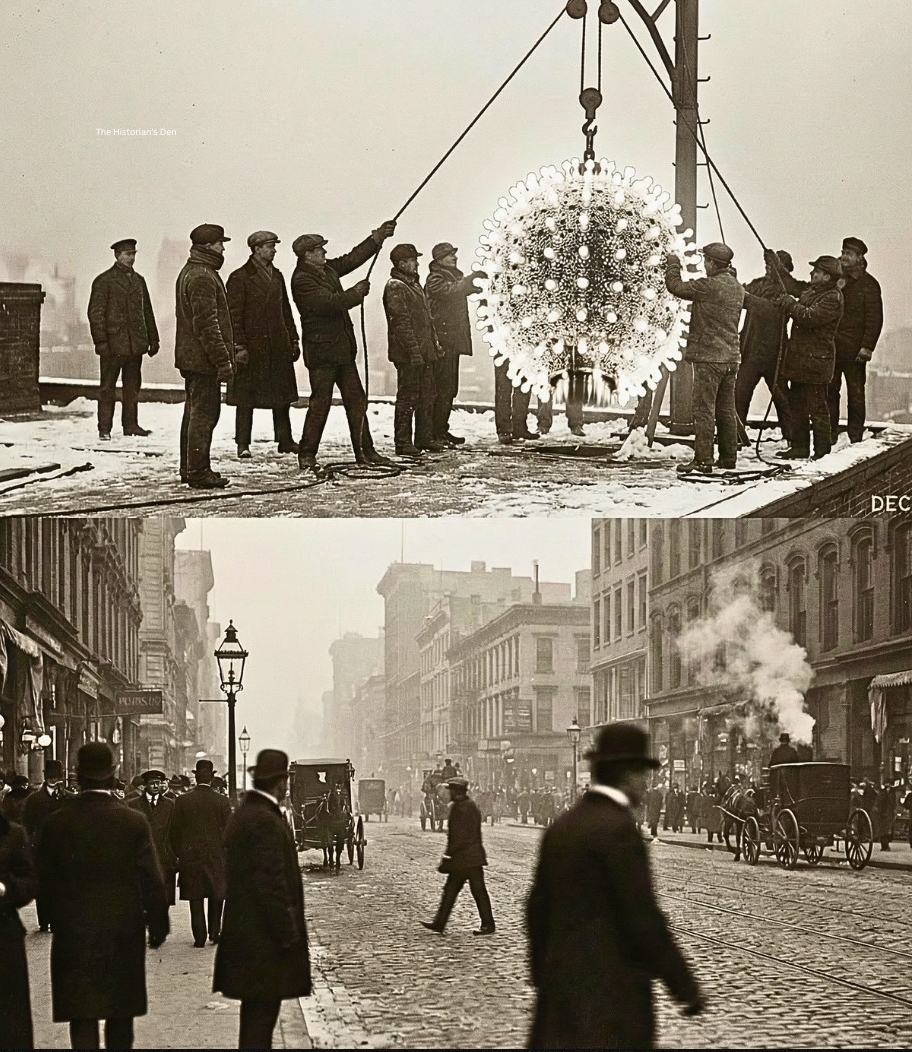

He needed someone to build it—someone young, precise, and unafraid to hoist a 700‑pound experiment over a city.

He found him in **Jacob Starr.**

# The Metalworker Who Made Midnight

Jacob Starr was a young metalworker, not a celebrity, not a headline name.

But on Ochs’s commission, he became the engineer of a new tradition.

His instructions were ambitious:

– Create a sphere big enough to be seen from the streets.

– Make it sturdy enough to survive winter winds.

– Light it so it glowed in the night.

– Mount it so it could rise, wait, and then fall exactly when commanded.

What he built was this:

– **An iron and wood ball**

– **Five feet in diameter**

– Weighing about **700 pounds**

– Studded with **100 incandescent light bulbs**

It was:

– Industrial and elegant.

– Heavy, but graceful in concept.

– Part machine, part lantern, part symbol.

It would be placed at the very top of the flagpole on the roof of **One Times Square**, the New York Times building.

On December 31, 1907, it would have its first test.

December 31, 1907: The Night the Sky Stayed Dark but the City Didn’t

It was a strange New Year’s Eve.

For the first time, there would be **no legal fireworks** above Manhattan.

– No explosive finale.

– No crackling sky.

– No shower of embers over the rooftops.

But at the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue, a crowd was already forming around the New York Times building.

Word had spread: something new was going to happen at midnight.

# Lobster Palaces and Electric Hats

The surrounding restaurants—known in that era as **“lobster palaces”** for their extravagant menus and flashy décor—were packed.

Inside:

– Waiters moved through the rooms balancing trays and champagne.

– Diners in evening clothes laughed, gossiped, and speculated about the odd new “stunt” atop the Times building.

Some of those waiters wore something that must have looked downright futuristic:

**Battery‑powered top hats** that lit up with the glowing numbers **“1908.”**

It was a small detail—but a telling one.

Electricity was still new enough to feel magical.

A ball covered with light bulbs, dropping in the cold winter air over a city of steam and stone, would not feel like a compromise.

It would feel like an announcement:

**New York could adapt. And it could do so with style.**

# The First Descent

As midnight approached, all the complicated moving parts converged:

– The crowd in the streets.

– The people at their windows.

– The diners in the restaurants.

– The workers on the roof, ready to control the ball’s slide.

Up above, the 700‑pound iron and wood sphere glowed against the night.

Seconds before midnight, it began to descend down the flagpole.

No explosion.

No blast wave of sound.

Just **anticipation**.

People watched:

– Heads tilted back.

– Breath visible in the cold air.

– Hands clutching each other or lifted in excitement.

The ball was doing what Ochs had wanted:

It was **measuring the last moments of one year and the first instant of the next**, in a way everyone could *see*.

When it reached the bottom at exactly midnight, the crowd roared.

The fireworks were gone.

But something new—and in some ways more powerful—had taken their place.

A tradition was born.

From Local Stunt to Global Ritual

Nobody standing in Times Square that first night could have predicted what the ball would become.

To them, it was a clever workaround.

A show for a city frustrated by new restrictions.

An answer to a problem created by a law.

But the idea lodged itself in the public imagination.

Year after year, the ball came back.

– The materials changed.

– The design evolved.

– The technology improved.

But the core ritual remained:

**Light up the night, count down the seconds, and let something visible fall as the year begins.**

# How a Silent Drop Became the World’s Loudest Moment

As decades passed:

– Radio arrived.

– Then television.

– Then global satellite broadcasts.

What began as a purely local spectacle turned into:

– A **national** event.

– Then an **international** one.

– Eventually a **global New Year’s symbol** watched by more than a **billion people**.

People far from New York, who had never walked Broadway or seen the Times building in person, began to think of the Times Square ball drop as the **official start of the year.**

They could have chosen fireworks in Sydney or chimes in London.

But over time, the image that stuck was this:

A glowing sphere descending slowly over the massive crowds of Times Square, cameras capturing faces from around the world, voices counting down in unison:

Ten.

Nine.

Eight…

A ritual that began because **fireworks were banned** became more iconic than fireworks themselves.

The Irony at the Heart of the Tradition

It’s easy to see the Times Square ball drop as pure celebration—neon, music, confetti, stars, and corporate branding.

But if you strip it back to its bones, the origin story still has teeth:

– It started with a **ban**, not a party.

– It was borrowed from **maritime logistics**, not show business.

– It was engineered by a **metalworker**, not a designer or artist.

The drama came later.

Underneath the glitter is something surprisingly modest:

A very old human desire to mark the moment when **time changes**.

To make the invisible visible.

To say, “This second right here is the border between what was and what will be.”

The fireworks were loud but imprecise.

The ball was silent but **exact**.

In that sense, Ochs didn’t just replace spectacle.

He replaced it with **symbolism**.

The ball isn’t just a decoration.

It’s a clock you can *feel* with your whole body.

A Banned Explosion, a Borrowed Tool, and a Bit of New York Genius

The official story of the Times Square ball drop fits neatly in a sentence:

In 1907, with fireworks banned, New York Times publisher Adolph Ochs borrowed the idea of the maritime time ball and commissioned Jacob Starr to build a 700‑pound illuminated sphere that would drop at midnight from the flagpole atop One Times Square, creating a new New Year’s Eve tradition.

But inside that sentence is an entire world:

– A city struggling with modernization and public safety.

– A publisher determined to keep the public’s attention.

– A forgotten craftsperson literally building the symbol of the future.

– A quiet nautical invention turned into a global celebration.

The next time you watch the ball drop—

– Whether on TV,

– On your phone,

– Or from the freezing streets of Manhattan—

you’re not just watching a party trick.

You’re seeing the echo of:

– Fireworks that once shook the city.

– A ban that threatened to silence its favorite moment.

– A publisher who thought, **What else could fall at midnight?**

– And a young metalworker who answered, **This.**

From a harbor tool to a skyscraper spectacle.

From a maritime noon signal to a midnight world event.

What began as a workaround for a banned firework has become the way the planet tells itself, once a year, that time is moving forward—and we’re moving with it.

All with a ball that falls, precisely, out of the night sky in New York.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load