November 7, 1849. Savannah’s public market. A pregnant young woman stands bound at the waist-high rail—five months along, wrists raw, priced not at $19 but 19 cents. Less than a pound of coffee. The auctioneer’s voice carries; the crowd shifts; even hardened traders look uneasy. The low price isn’t charity. It’s humiliation engineered to attract a specific type of buyer. The deed is immaculate, the minimum bid is obscene, and the city will spend the next eighty years trying to bury what happened next.

Her name appears twice in official papers—spelled differently both times. Dinah in one ledger. Diana in a coroner’s report six years later. She called herself Dinina when she finally spoke. Her story moves from rape in a “respectable” Charleston household to a rigged sale in Savannah, to a bidding war that escalates from pennies to $1,200, to an escape that threads the Underground Railroad by ship and by wagon, to a return south years later to rescue the child who was sold from her arms. Along the way: murder, sealed evidence, and a plantation secret so vicious that when it was unearthed in 1931, the authorities locked the files and forbid public discussion.

This is the chapter Savannah tried to erase. Here’s how the trap was set—and how one woman and a network of hidden allies broke it.

Savannah’s Market, Charleston’s Respectability, and a Price Meant to Wound

Savannah’s auction platform was the city’s stage of commerce—furniture, livestock, and human beings, sold under the same Greek Revival façade that made brutality look orderly. Cyrus Feldman, the auctioneer, had a reputation for efficiency. He could read a crowd, press a bid, and keep his hands steady even when nerves rattled through the floorboards.

The paperwork for Lot: Dinah looked routine at first glance: age ~22, five months pregnant, domestic skills. Then came the minimum: 19 cents. It didn’t signal defect; it signaled vengeance. In 1849, a healthy, childbearing woman often sold for $700–$900. Price communicates intent. This price was engineered to summon a specific buyer profile—men who specialized in extracting value from “damaged” people quickly and violently.

Why so low? The name behind the sale explains everything.

In Charleston, Dinina had been owned by a tobacco merchant and deacon named Elias Cartwright. Publicly—church, chamber, charity. Privately—serial rape of a teenage girl he owned, later selling her first child, Ruth, for $400 to erase evidence. When Dinina became pregnant again, Elias’s wife confronted not her husband, but the girl—blaming seduction and demanding removal. Elias needed her gone far enough that his respectability stayed intact. He forgave a Savannah merchant’s debt—$800—in exchange for logistics: get her to Savannah, set the minimum at 19 cents, make sure the buyer fits the pattern.

Savannah was told the price. It wasn’t told the plan.

The Auction That Turned into a Duel

Feldman read the bill of sale and the crowd balked. “Nineteen cents?” Questions flew about disease and defect; Feldman refused to lie. The price reflected “a personal matter,” not a physical issue. Three men remained interested:

– William Hadley, the Savannah merchant who arranged the sale.

– Thornton Graves, a planter known among enslaved people as Chatham County’s cruelest master—and a professional slave catcher with extra income tied to hunting fugitives.

– A stranger in travel clothes with a scar on his cheek and winter-colored eyes.

Hadley bid 19 cents. Graves countered. Then the stranger spoke: “Ten dollars.” From there, control left commerce. The price jumped—$50, $100—until Graves tried to end it with $300. The stranger didn’t blink. He escalated past logic: $1,200, cash.

Sold to “Jacob Marsh.”

Graves confronted Marsh in the doorway—expecting deference. Marsh declined the lesson. He led Dinina out into the sunlight, and the city understood it had just watched something other than a sale. It had watched a rescue disguised as ruin.

Who Was “Jacob Marsh”? And Why $1,200?

Two blocks from the market, Marsh helped her into a farm cart and drove past Savannah’s bright façades toward scrub and pine. Only in the trees did he speak like a man not performing for a crowd.

He said the quiet parts. Elias had sent her “to die”—not overtly, but structurally. Nineteen cents attracts buyers who extract value fast and leave bodies behind. Graves had a pattern: seven pregnant women in ten years, bought cheap, isolated in a barn, then gone. “Childbirth” or “runaway” on paper; screaming at night in truth; infants heard and then silenced.

Marsh’s letter—folded and marked with a small bird—carried a message from Bethy, an elder in Elias’s household: the plan is in motion; trust Jacob; follow instructions; you are not alone. Bethy had watched for years, connected to an abolitionist network hidden in ordinary rooms. Elias’s household had furniture. It also had eyes.

Jacob Marsh told the truth about his name, too. He was Jacob Brennan of Pennsylvania, and he worked with the Underground Railroad—safe houses, false identities, and routes carved through hostile maps. He bought Dinina to stop Graves from adding her to a list no ledger wanted to record. Saving her was rescue and strategy.

The cabin where he hid her—the one where Sarah and her daughter Hannah kept fire and beans and quiet—wasn’t random. It was part of a local network designed to hide in plain sight while the roads were watched. Graves was a hunter. Hunters look for movement. The safest place—temporarily—was stillness.

Graves’s Pattern in Ink: A Journal of Murder

Sarah brought out a leather journal kept by Abigail, who had lived and died in Graves’s orbit. The entries were dated and specific. Names—Rachel, Margaret, others unnamed—arrived pregnant, were isolated in the old tobacco barn, screamed, “ran away,” and never returned. Abigail heard a newborn’s cry stop like a knife. She tracked the events like evidence. Systematic acquisition, isolation, disappearance. No medical care. No community. No record beyond whispers.

Why? The journal couldn’t answer motive with certainty—only pattern. Graves bought pregnant women cheaply, kept them away from other enslaved people, and neither mothers nor infants survived. It wasn’t economics. It was something darker, enabled by law that recognized ownership instead of humanity.

Stopping it required humiliating Graves publicly, then outrunning his anger.

The Escape Plan: Not Overland—By Sea

Brennan’s face turned drawn. Graves knew he had been outbid by a stranger and started asking questions—hotel registers, cash, routes. “Jacob Marsh” didn’t exist on paper. Brennan needed to make him disappear and move Dinina on a path Graves wouldn’t expect.

He chose water. A sympathetic captain—Samuel Porter—was leaving for Philadelphia in five days. The plan: hide her in the cargo hold; deliver her to Thomas Garrett in Wilmington; let Garrett guide her through the chain into Ontario.

The cargo hold was five feet by three—dark, damp, and barely air. Porter would bring food and water twice daily. Seven days at sea, if the weather held. Brennan pressed money—$50—for her future and told her the truth about risk. Childbirth at sea is dangerous. But staying in Georgia meant Graves.

She climbed behind crates, Porter sealed the space, and the ship set out at dawn.

The Storm, the Silence, and the Sailor

On day three, a storm hammered the ship until the hull felt like a living thing trying to throw its cargo into the ocean. Crates shifted; barrels rolled; ropes swung. Deliberate calm gave way to survival instinct. Dinina braced and prayed—not for miracles, but for wood not to crush her and water not to fill the hold.

When the storm passed, Porter didn’t come. No food. No water. Hours became a day; a day became two; thirst turned cruel. On day three, light flooded the gap. A young sailor—Michael—lifted a canteen and told her the truth. Porter had fallen and broken his neck during the storm. Before he died, he told Michael where she was and what mattered: keep her alive.

Michael fed her slowly, reset the crates, and promised: Wilmington tomorrow. Then Thomas Garrett would take her north.

He kept his word.

Wilmington: Thomas Garrett Takes the Wheel

Garrett met the ship with quiet competence. He and Michael carried her up the ladder, hid her under blankets, and drove into the city’s edges. The plan was measured: rest in a safe house; then move at night through Pennsylvania and New York to Canada. Garrett’s track record—over two hundred people guided to freedom—was built on patience, caution, and refusal to accept loss.

In a small house that smelled like soup and clean linen, Garrett’s wife Rachel fed her. Dinina saw free territory for the first time and let herself imagine what it could mean: a child born under law that recognized his life.

Frederick Douglass later told her the sentence that became instruction: your survival is resistance; your testimony is justice. Do not remain silent.

She didn’t.

The Border, the Breath, and the Name

January 1850, Ontario. Eight months pregnant, bones aching from winter and weeks of hiding, she crossed into legal freedom on frozen ground. She fell to her knees not because fatigue demanded it, but because reality did: she had survived. The Underground Railroad had a thousand hands. Some were men like Brennan, Garrett, Porter, and Michael. Many were women like Sarah, Hannah, Rachel, Clara. Each worked in the open secret of quiet rooms.

Three weeks later, she gave birth to a son after eighteen hours of labor. The midwife’s name was Clara. The baby’s name became Jacob—after the man who spent $1,200 to buy her life.

She settled in Dawn, Ontario—a Black settlement near the border—and built a life that refused erasure: seamstress, teacher’s helper, reader, writer. She married Samuel Richards, a blacksmith who understood that freedom does not erase wounds; it gives them space to heal. They added two daughters to the family. And then she went back south.

The Return for Ruth

Six years into freedom, a Quaker missionary sent a lead: a girl named Ruth, light-skinned, working outside Charleston. She remembered her mother. The rescue was incredibly dangerous—returning to slave territory as a free woman required courage sharper than weapons. Two experienced conductors guided her. They entered the cabin at midnight, woke Ruth gently, and left before the world could put chains back on history.

They reached Canada in October. When Ruth met her mother, she learned what resilience looks like when it refuses to die.

Completeness is rare in stories like this. She earned it.

War, Occupation, and the Cellar Under Graves’s Tobacco Barn

In 1863, Union forces occupied Savannah. A Black regiment searched Thornton Graves’s plantation. Sergeant Isaiah Freeman noticed newer planks in the old tobacco barn, pried them up, and found a concealed cellar. Inside: bodies—eight women; infants; canvas-wrapped remains; skulls marked by violence. Testimony from formerly enslaved people documented the pattern: pregnant women purchased cheaply, isolated, then gone. Babies heard, then silenced. Graves had used law, wealth, and isolation as his cover.

Captain Henry Clark prepared a report—evidence for war’s moral ledger. It fell into archive—a casualty of priorities and Reconstruction weight.

Graves fled south, died in Mississippi under an assumed name in 1867, never prosecuted. His estate unraveled quietly. The land passed through hands. In 1921, a Black farming cooperative bought part of it. In 1968, farmers found bones the 1863 excavation missed. Authorities reburied the remains under a marker: “Victims of slavery, 1843–1862. May they rest in peace.” Not justice. Not enough. But a name given where none had been.

In 1931, Emory graduate student Patricia Whitmore found Captain Clark’s report, wrote an article, and faced legal pressure from the Graves descendants’ lawyer. She sealed her research “to be opened fifty years after my death.” The envelope opened in 2024. The National Museum of African American History and Culture now holds the documents. The record exists. The silence no longer does.

The People Who Fought, and the Ledger They Created

– Jacob Brennan continued Railroad work until war, then served as Union intelligence. He died in 1879 in Pennsylvania.

– Sarah and Hannah operated their safe house until 1861; later moved north to help freed people adjust to life beyond property.

– Elias Cartwright died in 1865—bankrupt, alone, obituary sanitized. Constance lived twenty more years, never publicly accountable.

– William Hadley disappeared from records after 1863.

– Cyrus Feldman kept selling until abolition; tried goods-only; died in 1867—likely yellow fever.

Graves’s memory is a lesson: wealth can hide atrocity for a time; evidence outlives reputation.

Why Savannah Buried the Story—and Why It Matters Now

Cities prefer archives that protect comfort. Sealed records, vanished ledgers, restricted access “pending review.” But numbers don’t lie when read properly. Nineteen cents was engineered humiliation. $1,200 was engineered resistance. Eight bodies and infants were engineered murder. Every number here has a human attached to it.

This is a family story—Cartwright’s household, Graves’s plantation, Sarah’s cabin, Dawn’s settlement. It’s a system story—law, church, commerce, and reputation combining to keep cruelty intact. It’s also a resistance story—conductors, captains, seamstresses, midwives, missionaries, and journalists carrying pieces of truth until someone assembles them.

It’s platform-safe because it tells the truth without graphic detail and honors victims without sensationalizing. It’s potent because it refuses euphemism.

The Slow-Burn Cadence That Keeps You Reading

You started at the rail with nineteen cents. You watched a duel that turned a commodity into a life. You hid in a cargo hold through a storm and a death. You met the sailor who kept his promise. You watched Thomas Garrett lift someone from darkness into the cold light of a free evening. You crossed the border. You named a child. You went back south. You found Ruth. You found bones under a barn. You opened an envelope and read the report that turned rumor into proof.

You felt uncomfortable because stories like this force a choice: accept the myth or accept the ledger.

Choose the ledger.

Key Takeaways That Cut Through Myth

– Price is narrative. Nineteen cents was meant to crush dignity and attract cruelty; $1,200 was meant to break a pattern.

– Silence isn’t consent. Servants hear; elders organize; networks grow in rooms where powerful people think no one is listening.

– Memory outlives suppression. A captain’s report, a student’s sealed envelope, a museum’s archive—truth finds doors.

– Resistance scales through care. Beans, blankets, letters, rides, and names are infrastructure; they turn survival into history.

Coda: The Last Page in Her Hand

In Dawn, Ontario, Dinina kept a journal—forty years of unsanitized life. On the final page, she wrote what the courtrooms and columns wouldn’t:

“I was sold for nineteen cents because a man wanted me to believe I was worthless. I was never worthless. I survived because people who understood that truth risked everything. I am not special. I am one among millions. Remember them.”

The market is gone. The platform dismantled. The city’s memory curated. But the ledger exists—in archives, in journals, in bones found by accident, in names stitched into stories by people who refuse erasure.

Read this story. Share it. And understand why Savannah tried to keep it sealed.

Full citations and archival notes compiled from the narrative you provided—link in the comments.

News

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but…

U.S Nurse Treated a Japanese POW Woman in 1944 and Never Saw Her Again. 40 Years Later, 4 Officers

The rain hammered against the tin roof of the naval hospital on Saipan like bullets. July 1944. Eleanor Hartwell wiped…

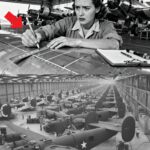

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory on Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Boot Lace Trick” Took Down 64 Germans in 3 Days

October 1944, deep in the shattered forests of western Germany, the rain never seemed to stop. The mud clung to…

Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open

17th April 1945. A muddy roadside near Heilbronn, Germany. Nineteen‑year‑old Luftwaffe helper Anna Schaefer is captured alone. Her uniform is…

End of content

No more pages to load