In September 1802, a Richmond newspaper published a story that shook the nation. It claimed President Thomas Jefferson was keeping one of his slaves, Sally Hemings, as a concubine and had fathered several children with her. Jefferson’s enemies seized the scandal, newspapers printed obscene caricatures, and sermons condemned him from the pulpit. Jefferson never responded—no denial, no confirmation—maintaining a silence that would last two centuries.

What the paper did not reveal was even more disturbing. Sally Hemings was the half-sister of Jefferson’s late wife, sharing the same father. When Martha Jefferson died, Jefferson inherited Sally—who was nine years old. Eighteen years later, Sally had borne six children, all by the same man, all born enslaved, all light-skinned enough to pass as white, and all bearing Jefferson’s face.

How did the author of the Declaration of Independence end up with a secret family by his wife’s sister? How did a 16-year-old girl become pregnant by the most powerful man in America? Why did Sally return from Paris when she could have claimed freedom? And how did they live under the same roof for 38 years without intervention? The answers begin in 1787, when Jefferson took Sally to Paris and made a promise that changed both their destinies.

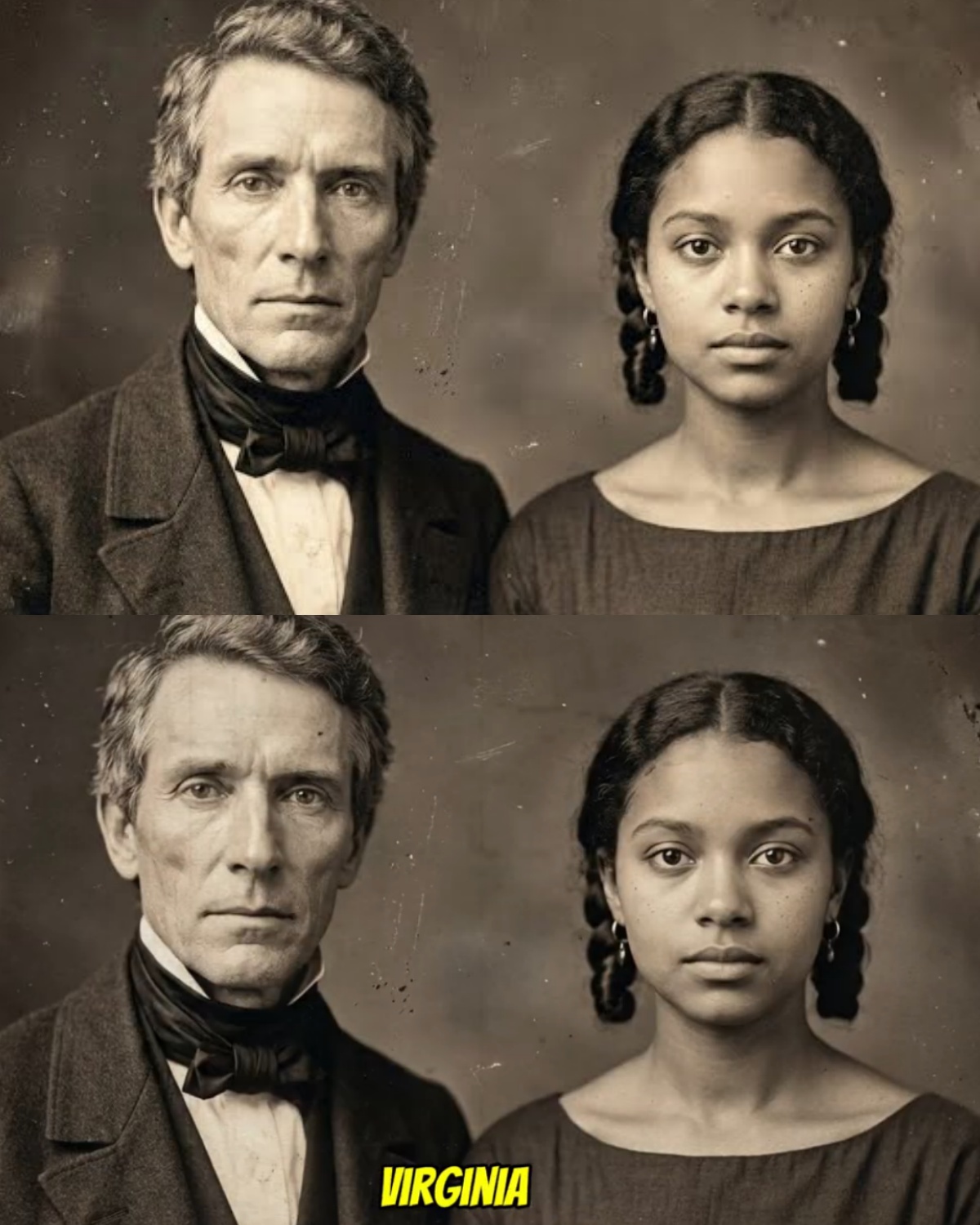

Virginia, 1782. Jefferson, age 39—lawyer, politician, architect, and philosopher—had written the Declaration six years earlier and owned Monticello with hundreds of enslaved people. In September, his wife Martha died after their sixth child. Devastated, he vowed never to remarry and kept that promise—finding another way to avoid being alone.

Martha brought land, money, and slaves into the marriage, including the Hemings family. The matriarch, Elizabeth Hemings, had twelve children, six fathered by Martha’s father, John Wayles. One of those children was Sally. She was nine when Martha died, light-skinned with long straight hair, and became Jefferson’s property.

Sally did not work in the fields like other enslaved children. She was assigned to the main house—maid, kitchen helper, table service—close to the white family. Jefferson enforced strict rules on which enslaved people entered the house—but the Hemingses, Martha’s kin, had privileges others did not. Sally grew up as Jefferson’s political career pulled him away.

In 1784 Jefferson left for Paris as minister, bringing his eldest daughter Patsy. He missed his younger daughter Polly and in 1787 asked for an adult woman to accompany Polly across the Atlantic. Instead, a letter arrived: Polly had traveled with fourteen-year-old Sally—pleasant, attentive, caring for Polly during the voyage.

Jefferson did not object to the change and arranged their travel from London to Paris. Sally arrived in mid-July to a city bursting with life. Jefferson welcomed Polly, then looked at Sally—now tall, slender, light-skinned, with features that resembled Martha. It was like seeing his late wife as a living memory.

Jefferson decided Sally would stay in Paris to care for Polly. He paid for her to learn French, fine sewing, and French manners. For two years Sally lived in a city where slavery had no legal standing and enslaved people could petition for freedom. On French soil, she could have walked away.

But she was fourteen, alone, with no money or family beyond the Jeffersons. She learned quickly, and Jefferson watched—how she moved, learned, and evoked Martha with every gesture. Between 1787 and 1789, a relationship began. He was 44, she was 16; he was the U.S. minister to France, she was his slave. In such an unequal power dynamic, consent had no real meaning.

In autumn 1789, Washington requested Jefferson as Secretary of State. Jefferson prepared to return to America, booking passage for his daughters, Sally’s brother James Hemings, and Sally. Sally refused. In Paris she had something like freedom, and she was three months pregnant.

According to her son Madison’s later testimony, Sally told Jefferson she would stay—her child would be born free. Jefferson could not legally force her in France. He begged and promised: she would have privileges, never work the fields, and all her children would be freed at 21. With no other path, Sally accepted and boarded the ship back to Virginia.

Sally arrived at Monticello in November 1789, five months pregnant. No one asked questions. She was returned to the main house—near Jefferson and his daughters—as if nothing had changed. In 1790, she gave birth; the baby died within weeks. Jefferson wrote nothing of it.

Jefferson traveled often as Secretary of State but returned frequently to Monticello. Sally lived in the south dependency, in a room close to Jefferson’s—a highly unusual arrangement for an enslaved woman. In 1795, Sally gave birth to Harriet, light-skinned enough to pass as white. The child died at two.

In 1798, she bore Beverly, who survived and grew strong, light-skinned, with Jefferson’s features. Beverly worked as a carpenter and musician and lived in proximity to the big house. In 1799, another baby was born and died in infancy. By then, Jefferson was vice president. He kept returning to Monticello—and to Sally.

In 1801, Sally bore another Harriet—this one survived. She was beautiful, light-skinned, with straight hair and blue eyes, appearing white. That same year Jefferson became president. He lived in Washington but returned to Monticello frequently—an arrangement that kept his secret close.

By 1802, the long-suspected truth exploded publicly. Journalist James Callender—once Jefferson’s ally—published the claims about Sally and Jefferson’s children. He listed names, ages, and descriptions. The story spread, enemies attacked, cartoons mocked, and sermons condemned. Jefferson remained silent.

Jefferson was reelected in 1804 and continued returning to Monticello. In 1805, Sally had Madison; in 1808, she had Eston—the lightest-skinned of all, able to pass completely for white. Later, Eston adopted the name Eston Hemings Jefferson, taking the surname he was denied legally but held by blood.

Sally had seven children by Jefferson; four survived to adulthood—Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston. All were born enslaved because the law followed the mother’s status. Even if their father was the President who wrote “all men are created equal,” the law protected him—not Sally.

Jefferson finished his presidency in 1809 and returned to Monticello. He was 66; Sally was 36. She had borne six of his children, lost two, and remained enslaved. Life settled into a routine: Jefferson in the main house with white family; Sally in a small room in the south building connected by a passageway; her children nearby with privileges others lacked.

Visitors noticed the light-skinned Hemings children. Enslaved workers answered evasively—“They’re Hemings family. They have white blood.” Everyone knew whose. Few said it aloud. Isaac Jefferson later recalled Sally’s proximity to the family and that she never worked the fields, but he avoided naming the relationship. Jefferson’s daughters likely suspected but denied it publicly.

Jefferson’s debts ballooned. He owed the modern equivalent of over $2 million. When he died, the plantation and enslaved people would be sold. Virginia law allowed manumission in wills. Jefferson, who had freed few, chose to free five enslaved people—two of Sally’s brothers and three of her sons: Beverly, Madison, and Eston. He fulfilled his Paris promise to free their children at 21.

He did not free Sally. Her name was absent from his will. Perhaps he thought informal freedom would follow; perhaps he did not care. On July 4, 1826, Jefferson died at Monticello at age 83—celebrated as a founding father, author of the Declaration, and statesman. Newspapers exalted him. No one mentioned Sally Hemings.

Sally was not formally freed, but Jefferson’s daughter Martha allowed her to leave Monticello. Sally moved to Charlottesville, living with Madison and Eston. She was 53 and de facto free, though legally enslaved until her death in 1835 at age 62. In the 1830 census, Sally and her children were recorded as white.

The four surviving Hemings children chose different paths. Beverly left in 1822, married a white woman, lived as white, and erased his past. Harriet also left in 1822 with money from Jefferson, married white, and kept the secret. Madison was freed in 1826, married a free Black woman, lived as Black, and in 1873 publicly told the full story.

Eston was freed in 1826, stayed in Virginia, then moved to Ohio in 1852 and adopted the surname Jefferson. He and his family lived as white. His descendants knew their Jefferson lineage but erased Sally’s story. Jefferson’s white family denied the truth for 150 years, insisting the Hemings children belonged to Jefferson’s nephews.

Historians long rejected Madison Hemings’ testimony as unreliable—too uncomfortable to accept that a founding father had an enslaved family. In 1998, DNA testing compared Eston’s descendants with Jefferson’s male line. The result confirmed Jefferson paternity for Eston—virtually confirming the relationship and likely paternity of Sally’s other children.

In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation officially acknowledged the relationship and the children. Monticello’s exhibits changed—adding Sally’s story, her children, the Paris promise, and the 37 years they spent together. They also acknowledged Jefferson never freed Sally.

Jefferson died as a celebrated American icon. Sally died largely forgotten. Their children were free but had to hide or deny their origins to survive. Some chose whiteness; others chose Black identity; all carried a secret America preferred not to face. The man who wrote “all men are created equal” had six children with his enslaved wife’s half-sister and never publicly acknowledged them.

This is the story America buried for two centuries. It took science to force its return. It is a story of power and powerlessness, hypocrisy and survival—of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, and six children born in the shadow of the most powerful man in America. History often hides what it cannot explain. The truth, eventually, surfaces.

If you want more stories never meant to be told, subscribe to Cursed Legacies. Comment “The truth always surfaces” if you made it to the end. Join us next time as we unearth another buried chapter.

News

What MacArthur Said When Patton Died…

December 21, 1945. Tokyo, Japan. General Douglas MacArthur sits in his office in the Dai-ichi Seimei Building—the headquarters from which…

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Saved the 101st Airborne

If Patton hadn’t moved in time, the 101st Airborne wouldn’t have been captured or forced to surrender. They would have…

The Phone Call That Made Eisenhower CRY – Patton’s 4 Words That Changed Everything

December 16, 1944. If General George S. Patton hadn’t made one phone call—hadn’t spoken four impossible words—the United States might…

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

End of content

No more pages to load