They say Peter Pan never grew up.

What most people don’t know is that his creator quietly gave away the *right* to grow rich from that story—and in doing so, helped save thousands of real children’s lives.

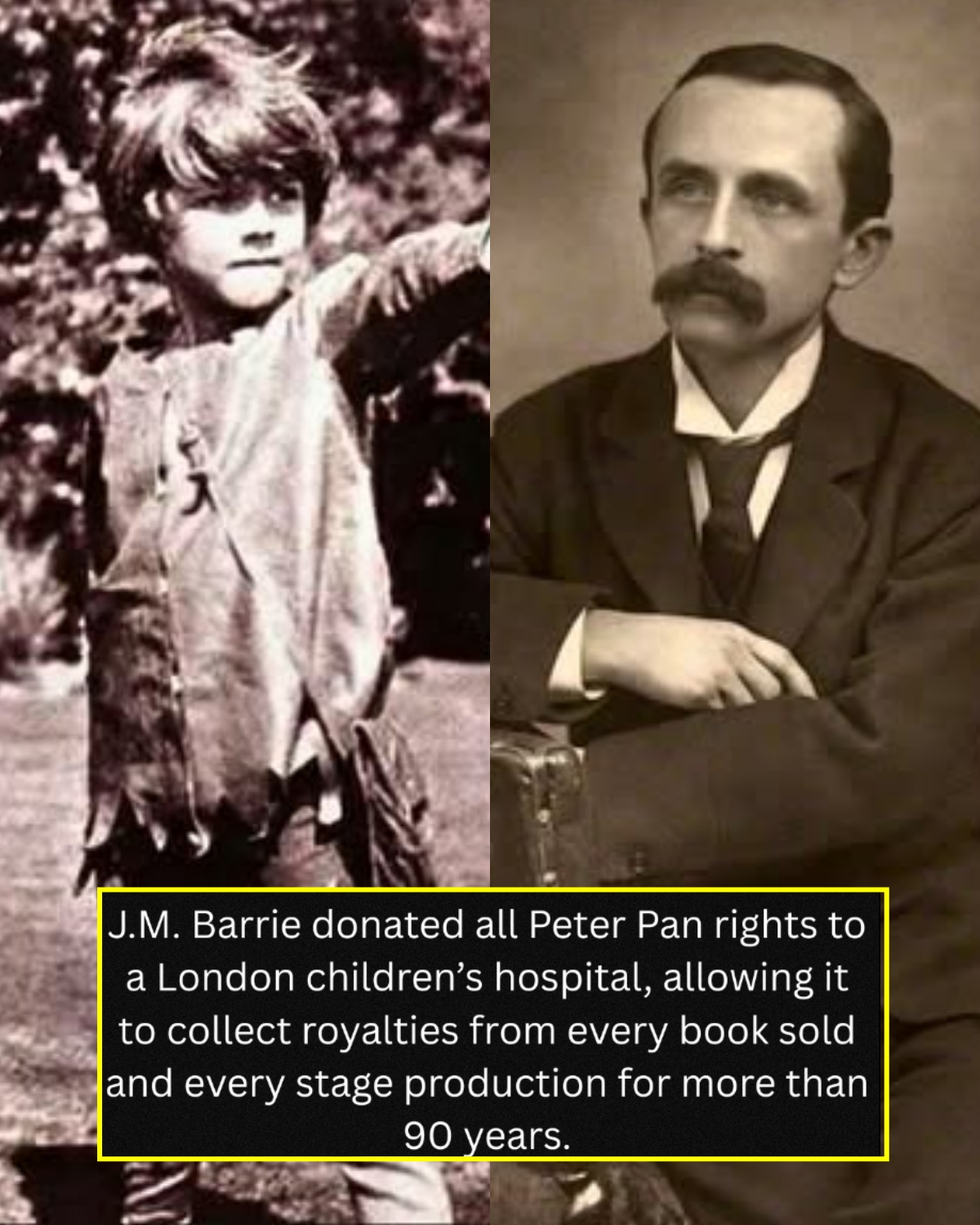

In 1929, at the height of his fame, **J.M. Barrie** signed away **all rights to “Peter Pan”**—not to his family, not to a publisher, not to a university, but to a children’s hospital in London. No press conference. No emotional speech. No self‑congratulatory interview.

He simply walked into **Great Ormond Street Hospital** and turned one of the most valuable stories in English literature into a **permanent lifeline** for sick children.

He never publicly explained why.

He refused all publicity.

He even asked the hospital **not to use his name** to raise money.

To the outside world, it looked like an eccentric act of generosity.

To those who knew his past, his grief, and the boys who inspired Peter Pan, it looked like something else: **a broken man quietly trying to turn a story about never growing up into a way of helping those who might never get the chance.**

The Day Peter Pan Became a Hospital Fund

By 1929, **James Matthew Barrie** was not just a writer—he was an institution.

– “Peter Pan” had become a phenomenon.

– The play had been performed countless times.

– The book was beloved worldwide.

He could have ensured that the royalties made **his heirs rich for generations**.

Instead, he did something so unusual that the lawyers didn’t even know how to process it.

# A Gift So Strange Lawyers Had to Invent New Forms

Barrie’s decision was simple on paper, but revolutionary in practice:

He **donated all his rights to “Peter Pan”**—including:

– **Book royalties**

– **Stage performance fees**

– **Adaptation rights** (within the legal frameworks of the time)

to **Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children** in London.

This wasn’t a symbolic gesture. It was the entire income stream from his most famous work.

The legal system wasn’t built for this.

Publishers were used to dealing with:

– Authors

– Estates

– Companies

They were **not** used to a children’s hospital owning the rights to a global literary sensation. Lawyers had to **draft new kinds of paperwork**. Contracts had to be reworked. Some officials weren’t even sure if it was *allowed*.

And yet, Barrie was clear.

These rights did not belong to him anymore. They belonged to the hospital—and, in a deeper way, to the **children**.

# A Gift So Quiet the Hospital Was Afraid to Talk About It

You might imagine the hospital would rush to announce such a staggering gift. They didn’t.

In fact, **Great Ormond Street Hospital initially kept it quiet.**

They were:

– Unsure how the public would react.

– Nervous about appearing to “profit” from a beloved children’s story.

– Uncertain how to use Barrie’s name without betraying his wishes.

Barrie had **explicitly asked**:

– No publicity stunts.

– No marketing around his generosity.

– No “J.M. Barrie wards” or grand plaques trumpeting his name.

He did not want a monument.

He wanted **money for medicine**.

So for a time, one of the greatest acts of literary charity in history ran almost **silently in the background**, feeding the hospital small but steady streams of income every time someone bought “Peter Pan” or staged the play.

Nobody outside the hospital and the publishing world truly understood what he had done.

Not yet.

The Boys Who Never Grew Up—and the Man Who Never Got Over It

To understand why Barrie gave away Peter Pan, you have to go back long before 1929—to a group of brothers who played in London parks and changed his life forever.

They were the **Davies boys**.

They became his **family, his heartbreak, and his inspiration**.

# The Real‑Life Lost Boys

The Davies brothers—George, Jack, Peter, Michael, and Nico—were the sons of Sylvia and Arthur Llewelyn Davies. Barrie met them in London’s Kensington Gardens around the turn of the century.

To them, he was:

– A funny, small, soft‑spoken man.

– A storyteller.

– A fellow conspirator in games of pirates, Indians, and flying boys.

To him, they were something much more.

He watched them:

– Run through the park.

– Turn sticks into swords and imaginations into universes.

– Talk about never wanting to grow up.

Those games, those boys, and those long afternoons became the **seed of Peter Pan**.

The names and faces blurred into myth.

The “Lost Boys” of Neverland weren’t one person—they were **all the Davies boys**, distilled into fiction.

But real life would not be kind to them.

# From Playtime to Guardianship

Tragedy came in waves.

First, the boys’ father, Arthur, fell ill and died.

Then, some years later, their mother Sylvia—whom Barrie loved deeply in his own quiet way—also died.

Suddenly, the boys were not simply his playmates or inspirations.

They were, in many practical ways, **his responsibility**.

Barrie helped raise them.

He:

– Paid their school fees.

– Supported them financially.

– Gave them a home, a structure, and as much love as a man haunted by his own childhood could offer.

He didn’t just write about lost boys.

He **lived** with them.

And he watched as tragedy continued to stalk them:

– One died young in World War I.

– Another struggled under the weight of being “the real Peter Pan.”

– Emotional scars, expectations, and grief followed them all.

Barrie had written a story about a boy who never grew up.

Real life gave him boys who never got the chance.

Many historians believe this is where the roots of his decision lie:

In his deep grief, his guilt, and his desperate desire to turn that pain into something **useful**.

Turning Fiction into Medicine

For most writers, the dream is immortality: a book that sells forever, a name that never disappears.

Barrie could have had that in a very traditional way—through wealth, estates, and literary fame. Instead, he chose something far more radical:

He made **Peter Pan’s success pay for children’s survival.**

# Every Copy, Every Ticket, Every Curtain Call

Barrie’s donation meant that **every time**:

– A child bought a copy of “Peter Pan,”

– A theatre put on the play,

– A producer revived the story,

money flowed—not into Barrie’s pocket, not into a millionaire’s estate—but straight into the accounts of **Great Ormond Street Hospital**.

His story about a boy who never grew up became a **funding engine** to help *real* children do exactly that: grow up.

This wasn’t theoretical. It was concrete:

– **Book sales** helped pay for equipment.

– **Performance royalties** helped sustain wards and staff.

– **Adaptations** turned imagination into **treatment, surgery, and research**.

For once, a work of pure fantasy was directly underwriting **real‑world healing**.

And then came the test that would prove just how vital this secret gift really was.

The War That Nearly Broke the Hospital—And the Story That Kept It Alive

When **World War II** engulfed Europe, London’s skyline wasn’t the only thing under attack.

Bombs fell. Families fled. Money dried up.

For charities and hospitals, the problem was brutal:

– Donations collapsed.

– Needs **skyrocketed**.

– The system strained under wounds, malnutrition, and a generation of traumatized children.

**Great Ormond Street Hospital** was no exception.

During those years:

– Resources were stretched to breaking.

– Fundraising was harder than ever.

– Emergency became the new normal.

And yet, in the middle of the chaos, one revenue stream did **not** stop:

**Peter Pan.**

People still read.

Theatres, when they could, still staged the play.

Publishers still sent royalties.

Barrie’s quiet act of generosity, signed in a different decade for reasons he never fully explained, became a **financial lifeline** when the hospital needed it most.

When donations disappeared and the war tried to swallow everything, “Peter Pan” kept paying the bills.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that countless children who walked through Great Ormond Street’s doors in those years—including some who might have lost their lives without care—owe part of their survival to a **fantasy about flying out of a bedroom window.**

The Most Unusual Law in British Literary History

Charity donations have limits. So do copyrights.

Under normal circumstances, a copyright expires after a set period (historically, around the life of the author plus several decades), and the work moves into the **public domain**—free for anyone to use.

“Peter Pan” should have followed that path.

Legally, the story’s **standard copyright protection ran out in 1987**.

But by then, something strange had happened.

Peter Pan no longer belonged only to literature or entertainment.

In a very real sense, he belonged to the **children**.

# When Parliament Bent the Rules for a Boy Who Never Grew Up

In 1987, as “Peter Pan” approached the end of its conventional copyright life, the British government faced a choice:

– Let the copyright expire and strip Great Ormond Street Hospital of a major source of income,

or

– Do something that had **never been done before**.

They chose the second option.

The **UK Parliament passed a unique legal provision** granting Great Ormond Street Hospital **the right to continue receiving royalties from “Peter Pan” stage performances in the UK indefinitely.**

Not 10 more years.

Not 50.

**Indefinitely.**

This was not a normal extension.

It was a **bespoke legal privilege**.

– No other book.

– No other play.

– No other author’s work has ever been granted this same treatment in British law.

It was a formal recognition of something that had quietly been true for decades:

“Peter Pan” was **no longer just a story.**

It was part of the national moral ledger—a promise that the success of this fictional child who never grew up would **permanently help real children grow up.**

# A Legal Echo of Barrie’s Belief

Barrie once said that Peter Pan “belongs to the children anyway.”

Decades after his death, Parliament effectively agreed.

They didn’t give the story to the public.

They gave its **benefit** to the children, forever.

Even today:

– Whenever a theatre in the UK stages “Peter Pan,”

– Whenever those lines are spoken under stage lights,

– Whenever an audience claps to save Tinker Bell—

some of the money from that performance helps pay for **equipment, research, and treatment** at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The boy who never grew up is still, in a quiet, legal, relentless way, helping real children grow up healthy.

The Man Who Refused to Take Credit

In an age when philanthropy is often accompanied by naming rights, photo ops, and carefully staged press releases, Barrie’s approach feels almost alien.

He had every opportunity to turn his gift into a **public monument to himself**.

He refused.

# No Plaques, No Campaigns, No “J.M. Barrie Wing”

When he signed over the rights, Barrie didn’t just decline publicity—he actively pushed it away.

He asked:

– That his name **not be used** as a fundraising tool.

– That the hospital not turn his donation into a spectacle.

– That the focus remain on the **children**, not the benefactor.

In a world obsessed with legacy, he tried his best to make his own invisible.

People bought tickets to “Peter Pan” without knowing they were funding hospital wards.

Parents read the book to their children without realizing they were indirectly buying medical equipment.

Audiences applauded, laughed, and cried without the slightest awareness that a portion of their ticket was going to help a child they’d never meet.

That was exactly how Barrie wanted it.

He didn’t want to be *thanked*.

He wanted children to be **treated**.

# Generosity as Quiet Reparation

We can’t know everything that went on inside Barrie’s mind.

But his life was marked by:

– A difficult childhood.

– Profound grief over the Davies boys.

– Lifelong struggles with loneliness and loss.

To some historians, his gift looks like **reparation**:

– For the boys who died too young.

– For the ways fame twisted the lives of those associated with Peter Pan.

– For his own sense of guilt and helplessness in the face of tragedy.

He couldn’t save everyone he loved.

But he could make sure Peter Pan did something **useful** in the real world.

Not as a monument.

As a **mechanism**.

A Story That Heals in the Background

Today, most people encounter Peter Pan as:

– A children’s book,

– An animated film,

– A stage musical,

– A pantomime at Christmas.

They rarely stop to think that **every performance in the UK** is doing double duty:

– Entertaining the audience,

and

– Sending money to the wards of Great Ormond Street Hospital.

# From Stage Lights to Surgical Lights

Royalties from “Peter Pan” help support:

– **Specialized equipment**

– **Medical research**

– **Training**, **treatment**, and **facilities** for critically ill children

No, a single ticket doesn’t buy a ventilator.

A single copy of the book doesn’t pay for a surgery.

But over years and decades, the stream of income adds up.

A fictional boy who refused to grow up is funding the very real infrastructure that helps *other* boys and girls grow up with:

– Beating hearts.

– Functioning lungs.

– Healthy futures.

Peter Pan doesn’t just fly across the stage.

Behind the scenes, he quietly keeps the lights on in hospital rooms where the stakes are far higher than whether Wendy will stay in Neverland.

The Secret at the Heart of a Classic

Most readers know Peter Pan for:

– “Second star to the right and straight on till morning.”

– The crocodile with the ticking clock.

– The shadow that won’t stay attached.

– The boy at the nursery window.

Few know about the document Barrie signed in 1929, or the wartime budgets his royalties stabilized, or the Parliamentary clause that still protects Great Ormond Street’s share of the play’s success.

And yet, when you look closely, it all fits.

Peter Pan is a story obsessed with:

– **Childhood**

– **Loss**

– **The fear of growing up**

– **The ache of those who never get the chance**

Barrie’s gift transformed that ache into action.

Every time the story is told, it remembers—not just in metaphor, but in money—the children who are fighting for a future.

Why This Story Still Matters

There are bigger fortunes in the world than the royalties to “Peter Pan.”

There are larger hospitals, grander philanthropic gestures, more visible donors.

But few stories bring together:

– A **deeply personal grief**,

– A **global cultural icon**,

– A **children’s hospital in need**,

and

– A **one‑of‑a‑kind law** that recognizes the moral weight of fiction.

J.M. Barrie did not have to give away his masterpiece.

He did not have to stay anonymous.

He did not have to keep his motives private.

He chose to.

And because he did:

– A play written in the early 1900s still funds 21st‑century medical care.

– A character who vowed never to grow up helps real children live long enough to do exactly that.

– A story about flight and fantasy has a very real, very practical impact on hospital floors and research labs.

The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up—and the Children Who Now Can

If you walk into **Great Ormond Street Hospital** today, you will see:

– Modern machines.

– Busy corridors.

– Exhausted parents.

– Brave children.

You might not see Peter Pan.

But he’s there—**in the balance sheets**, in the history, in the continued trickle of funds that helps the hospital do what it does.

He is:

– In the royalties that still arrive.

– In the performances that still pay.

– In the law that still protects the hospital’s rights in the UK.

And behind him, always, is a small Scottish man who knew better than anyone that stories can’t stop loss—but they **can** change what comes after.

J.M. Barrie once wrote about a boy who flew away from adulthood.

In real life, he took the money that story earned and sent it straight into the arms of the children who couldn’t fly away from anything—not from illness, not from hospitals, not from the long road back to health.

He believed Peter Pan “belongs to the children anyway.”

Nearly a century after he signed that quiet, revolutionary document, the world has proven him right.

Every time a curtain rises on “Peter Pan,” somewhere in Great Ormond Street Hospital a different kind of work begins:

Not make‑believe.

Not pretend.

But the **real magic** of medicine, care, and second chances—

funded in part by a story about never growing up, and a man who quietly decided that if Peter Pan was going to live forever, **other children should get the chance to, too.**

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load