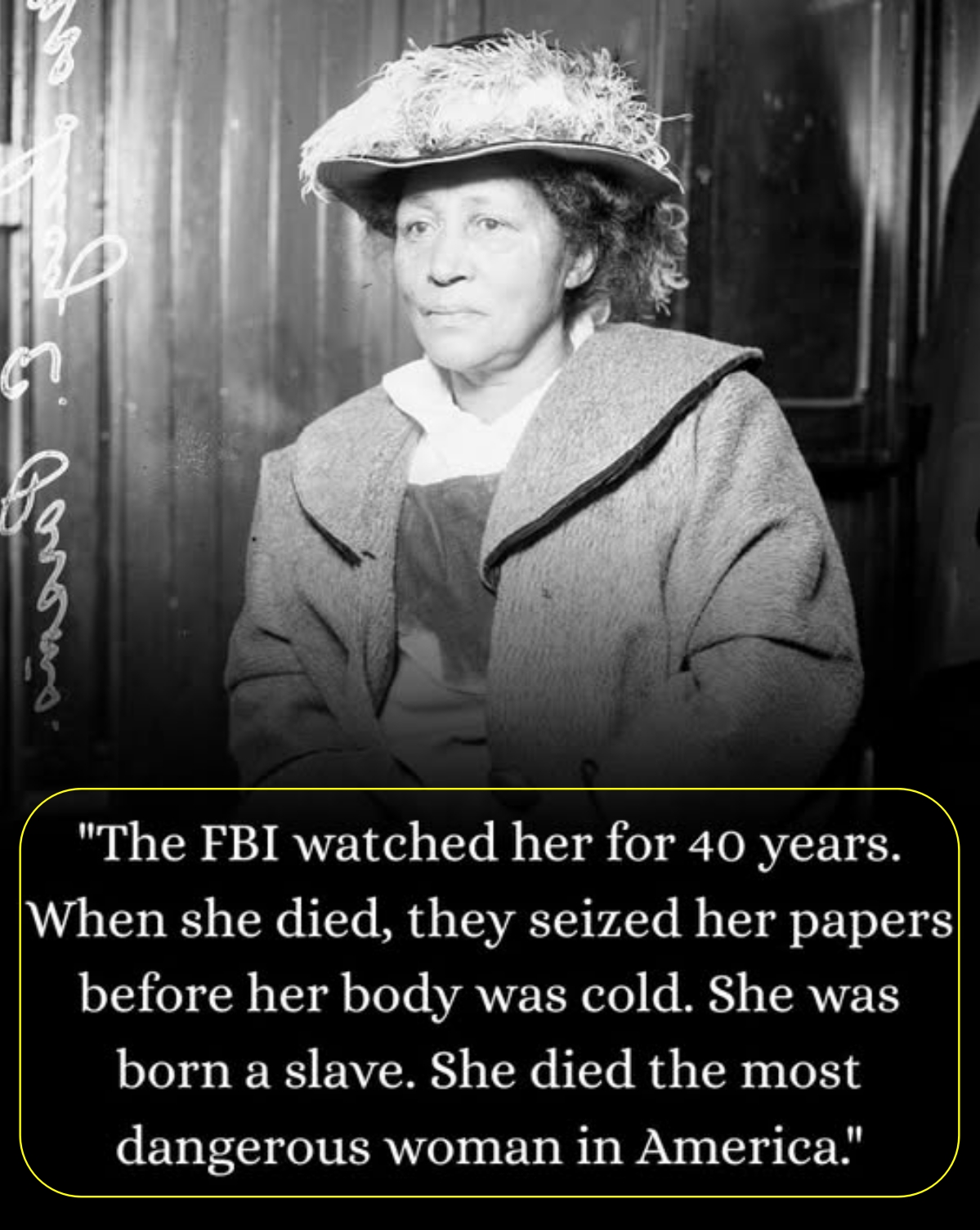

“The FBI watched her for 40 years. When she died, they seized her papers before her body was cold. She was born a slave. She died the most dangerous woman in America.”

Somewhere in Texas, a baby girl was born into slavery. She had no legal name, no birth certificate, no rights. The law said she was property—three-fifths of a person at most, nothing at worst. America had decided her fate before she took her first breath: she would be erased, forgotten, crushed under the weight of systems designed to destroy people like her.

She had African blood, Mexican blood, Native American blood. Every identity America was built on exploiting ran through her veins. But Lucy Parsons refused to vanish. And for the next 91 years, she would become the person the powerful feared most—not because of violence, but because of something far more dangerous: she gave the powerless their voice back.

When the Civil War ended and slavery collapsed, Lucy walked into freedom with nothing. She had no money, no family connections, no formal education. What she had was fury and brilliance. In Reconstruction Texas—where Black people were terrorized and freedom was often just a word—Lucy did something revolutionary: she taught herself to read, to write, and to think without asking permission from anyone.

Then she met Albert Parsons. Albert was a former Confederate soldier who had done the unthinkable: he rejected everything he’d been raised to believe. He renounced the Confederacy and became a radical advocate for workers’ rights and racial equality. In 1871, Lucy and Albert married.

It was an interracial marriage. In Texas. In 1871. It wasn’t just controversial—it was illegal. It was a death sentence. The threats came immediately: burning crosses, mobs at their door, warnings that they’d be lynched if they stayed.

So they fled north to Chicago, hoping to find the freedom Texas had denied them. What they found instead was a different kind of hell. Chicago in the 1870s was an industrial empire built on human suffering. Men, women, children worked sixteen-hour days in factories that chewed up bodies and spit out corpses.

There were no safety regulations, no minimum wage, no weekends, no rest. Get injured and you were fired and replaced by nightfall. Die on the job and your family starved. Lucy saw it all: crushed hands of child laborers, exhausted mothers collapsing between shifts, men dying in preventable accidents while factory owners got obscenely rich.

Something inside her broke—not in despair, but in fury. She started writing for radical newspapers, her words so sharp editors said they “cut through chains.” She spoke on street corners, under bridges, on factory floors—anywhere workers gathered to listen.

“We are the slaves of slaves,” she told crowds. “We are exploited more ruthlessly than our fathers ever were.” Thousands came to hear her speak. And the authorities started taking notes.

By the early 1880s, Chicago police had labeled her “more dangerous than a thousand rioters.” The Chicago Tribune, unable to reconcile her eloquence with their racism, called her a “beautiful fiend.” Lucy didn’t care what they called her. She just kept talking.

She helped organize unions and wrote pamphlets that spread across the country. She stood beside the poorest, most desperate workers in America and told them something revolutionary: you deserve better, and you have the power to take it. Then came May 4, 1886—the day that destroyed her life and proved she’d never be destroyed.

Haymarket Square, Chicago. A peaceful rally, workers demanding an eight-hour workday—eight hours to work, eight hours to sleep, eight hours to actually live. Someone threw a bomb at the police. Chaos erupted: gunfire, screaming, blood.

Seven police officers were killed. At least four civilians died. The authorities needed scapegoats. They arrested eight labor activists, including Albert Parsons.

There was no evidence connecting any of them to the bomb. No proof, no witnesses placing them at the scene. Just their political beliefs and their dangerous ideas about workers deserving dignity. They were convicted anyway.

Albert Parsons and three others were sentenced to hang. Lucy—barely in her thirties, with two young children—became a force of nature. She traveled the country begging for mercy, demanding justice, giving speeches that moved even people who hated everything she stood for.

Newspapers that despised her politics couldn’t stop covering her. She was that powerful. But in the end, she failed. On November 11, 1887, they hanged Albert Parsons.

Lucy arrived at the prison with their children, desperate to see him one last time. The guards turned her away. She collapsed outside the prison gates, her children crying beside her. Most people would have broken.

Most people would have retreated into grief, accepted that the powerful always win, and given up. Lucy Parsons woke up angrier than ever. For the next fifty-five years, she became unstoppable.

She spoke in Boston, New York, San Francisco—hundreds of cities. She warned about inequality, championed free speech, organized the poor. She wrote, she marched, she was arrested dozens of times.

And every single time, she got back up. The Chicago police kept files on her for over forty years. The FBI monitored her until the day she died. To them, she wasn’t just an activist; she was an existential threat to every oppressive system in America.

By the 1930s, Lucy was in her eighties—gray-haired, unbowed, still on Chicago’s streets giving speeches. She still demanded justice with the same fire she’d had as a young widow. “An injury to one is an injury to all!” she would shout to crowds who’d never forgotten her.

On March 7, 1942, Lucy Parsons died in a house fire at her Chicago home. She was 89 years old. Within hours—before her body was even cold—the FBI raided what remained of her house.

They confiscated her personal papers, letters, manuscripts, and a lifetime of writing. Sixty years of work, documents that could inspire people, ideas that could spark movements. They took everything and locked it away where no one could read it.

Even in death, they feared her words more than they’d ever feared her actions. But they failed. Because you can’t burn ideas. You can’t confiscate courage. You can’t erase someone whose voice echoes in every movement for justice.

Lucy Parsons’ words didn’t die in that fire. They lived on: in every fight for fair wages, in every woman who refuses to be silenced, in every person who looks at injustice and says, “No. Not anymore.”

Here’s why Lucy Parsons matters. She was born property in 1851. She died free in 1942, having spent nearly a century fighting not just for her own freedom, but for everyone’s. The powerful called her “the most dangerous woman in America.”

They were right—but not because she was violent. Not because she threw bombs or burned buildings. It was because she gave people something far more dangerous than violence: hope, language, and the belief that they deserved better, along with the tools to demand it.

She proved you don’t need wealth, power, or permission to change the world. You just need to refuse to be erased. The FBI tried to erase her. History tried. Poverty, racism, sexism, grief—all of it tried to silence her.

She outlasted them all. Remember Lucy Parsons: the girl born into slavery who taught herself to read. Remember the woman who married for love when it was illegal and deadly. Remember the activist who spoke for fifty-five years after they murdered her husband.

Remember that the FBI seized her papers because they knew ideas are more dangerous than armies. Remember that she was called “more dangerous than a thousand rioters”—and she earned that title not with violence, but with words. Remember that sometimes the most powerful weapon against injustice isn’t a bomb.

It’s a woman who refuses to shut up. Lucy Parsons was born property. She died a legend. And her voice? It’s still echoing.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load