It didn’t start with a roar.

It wasn’t the grinding screech of Tiger tank treads. And it wasn’t the terrifying banshee whistle of an incoming 88 mm shell.

It started with a sound so small, so insignificant, you could mistake it for a dry twig snapping under a tire.

A metallic click.

And then the world disappeared.

For a split second, gravity didn’t just shift. It reversed.

A 2½‑ton GMC truck was tossed into the air like a child’s discarded toy. Dust, twisted steel, and the fragments of what used to be a life were blended together in a black, suffocating cloud.

When the sound finally caught up to the visual, it wasn’t an explosion anymore. It was a physical punch to the chest.

That was how silence reigned on the roads to Germany in 1944.

Welcome to the Western Front, a place where the deadliest enemy wasn’t the Wehrmacht soldier retreating in desperation, but what he left behind.

Let’s rewind the clock to that autumn.

The United States Army—the greatest war machine in human history—was at its absolute peak. After the breakout from Normandy, we had liberated Paris and were tearing toward the German border at breakneck speed.

Morale was sky‑high. We had the Sherman tanks, we owned the skies, and we had a logistical supply chain so robust they called it the Red Ball Express, a literal river of steel that never slept.

But then everything started to slow down.

Not because we ran out of gas. Not because we ran out of ammo.

But because we hit a wall—an invisible one.

The Germans, masters of defensive warfare, knew they couldn’t stand toe‑to‑toe with American firepower in the open field anymore.

So they took the war underground.

They turned the muddy back roads of France, Belgium, and Holland into massive killing fields.

Their weapon of choice: the Teller mine.

It was a circular plate of metal, looking like an oversized dinner plate packed with TNT.

It sat quietly under the mud, under a pile of rotting leaves, or buried right inside an old tire track.

It was patient. It didn’t get tired. It didn’t need rations.

It just waited for the weight of a Willys Jeep or a troop transport to trigger the pressure plate.

For the drivers of the Third Armored, or the infantry of the Big Red One, every single yard of forward progress became a gamble with the devil.

Imagine you are a 20‑year‑old kid from a farm in Kansas or a block in Brooklyn.

You’re white‑knuckling the steering wheel of an open‑top Jeep. The wind is cutting your face, but there is cold sweat freezing on your spine.

You’re staring at the dirt road ahead, trying to analyze every shadow, every slight discoloration in the mud.

Does that patch of dirt look too fresh? Does that pile of debris look a little too organized?

The psychological strain was worse than a firefight. In a firefight, you can shoot back. You can find cover. You can see the enemy.

But with mines, you were helpless. You were fighting a ghost.

The paranoia spread through the convoys faster than a virus.

Even the most battle‑hardened veterans began to hesitate. They called it “mine psychosis.”

The result was a logistical catastrophe. Entire armored divisions built for lightning speed were forced to crawl at the pace of a pedestrian.

Tanks costing thousands of dollars sat idling, burning fuel. Thousands of tons of ammunition, gasoline, and food were backed up for miles, turning the supply line into a parking lot—sitting ducks for German artillery spotters and snipers.

General Patton, a man who lived and breathed the philosophy of constant attack, had to grind his teeth as he watched the tactical map stagnate.

The question on everyone’s mind was simple: How do we clear them?

At that time, our military doctrine was brutal and basic. The job of mine‑clearing fell to the combat engineers.

These were some of the bravest men in the service—but they were only human.

They had to get down on their bellies in the freezing mud. They had to crawl inch by inch.

In their hands, they held simple metal probes or the SCR‑625 mine detector, a heavy, cumbersome piece of electronics.

The process was agonizingly slow.

An engineer would sweep the detector back and forth like a pendulum. If he got a signal, he had to stop, gently probe the earth with a knife to locate the mine, and then neutralize it.

All of this while potentially under enemy fire.

The average speed to clear a narrow lane was measured in feet per hour.

It was an equation with no good answer. If we moved fast, we lost trucks and men to the mines. If we moved slow to clear them by hand, we lost the strategic initiative and let the enemy regroup.

We needed something different.

We needed a mechanical miracle. We needed something faster than a man on foot, but sharper than the eyes of a terrified driver.

We needed a solution that was distinctly American—pragmatic, bold, and borderline crazy.

And ironically, that solution didn’t come from a high‑tech laboratory in Washington or Detroit.

It started in the mind of a grease‑stained GI standing in the middle of a muddy field depot, surrounded by shell casings and broken machinery.

He was staring at his standard‑issue Willys Jeep with an idea that to anyone else would have sounded like a suicide mission.

But as the history of the Second World War proves time and time again, it is often the craziest ideas that unlock the door to victory.

And that key was about to be turned, right there in the mud of Europe.

Here is the brutal math of the battlefield—a calculation that kept generals awake at night and sent shivers down the spines of private soldiers.

In 1944, a fully equipped M4 Sherman tank cost the American taxpayer roughly $33,500.

A German Teller mine cost the Wehrmacht about ten bucks.

And in the freezing mud of the Rhineland, the $10 mine was winning.

It seems impossible, doesn’t it?

We had the industrial might of Detroit churning out steel behemoths. We had the atomic bomb in development. We had the proximity fuse.

Yet the only thing standing between an American convoy and total destruction was a man on his hands and knees holding a stick.

To truly understand the frustration, you have to look at the tools of the trade.

The standard‑issue mine detector, the SCR‑625, was a marvel of its time—but on the front lines, it was a beast.

It was cumbersome, temperamental, and heavy. The operator looked like he was vacuuming the worst carpet in the world.

He had to sweep the discs slowly—painfully slowly—left and right.

When the headset buzzed, the real nightmare began.

The machine didn’t tell you what was down there. It just told you *something* was down there.

It could be a lethal anti‑tank mine, or it could be a rusted horseshoe from World War I.

You didn’t know until you checked.

So the engineer would kneel in the slush. He would take out a bayonet or a metal probe and gently, with the touch of a surgeon defusing a bomb, poke into the earth at a 45‑degree angle.

If he hit something hard, he had to scrape away the dirt with his fingertips.

Imagine doing that for ten hours straight. Imagine doing that while mortar rounds are walking their way toward your position.

One slip of the wrist, one moment of impatience, and you simply ceased to exist.

It wasn’t just dangerous. It was agonizingly inefficient.

While these brave engineers played this high‑stakes game of poker with the ground, the war behind them ground to a halt.

A modern army runs on momentum. It is a shark. If it stops moving, it dies.

But the mines had turned the U.S. Army into a beached whale.

Behind the lead Jeep, you would see a sight that made logistics officers want to scream: a traffic jam stretching back five, maybe ten miles.

Two‑and‑a‑half‑ton trucks, fuel tankers, ambulances, mobile command posts—all idling, engines overheating, drivers leaning out of cabs, cursing the delay.

This was the logjam of death.

A stationary column is a target‑rich environment.

German forward observers, hiding in church steeples or tree lines miles away, would spot the dust cloud of a stalled convoy.

They would pick up their radios, dial in the coordinates, and rain hellfire down on the Americans.

Men died not because they were outgunned, but because they were stuck in traffic.

The pressure coming down the chain of command was immense.

The colonels were screaming at the captains. The captains were screaming at the lieutenants. And the lieutenants were pleading with the engineers.

Move it. We have to move.

But you can’t hurry a minefield. That is the physics of terror.

The situation was desperate. We were losing the most valuable resource we had: time.

Every hour spent probing the mud was an hour the enemy used to reinforce their next line of defense.

The Army needed a breakthrough.

They didn’t need a better bayonet. They didn’t need a braver engineer—God knows the ones they had were brave enough.

They needed speed. They needed a way to sweep the roads at the speed of the advance, not the speed of a crawl.

In the rear echelon, the brass was sending urgent requests back to the States for new technology. “Send us something faster,” they telegraphed.

But research and development takes months. Shipping takes weeks.

The boys on the line didn’t have weeks. They barely had minutes.

The solution wasn’t going to come from a laboratory at MIT.

It wasn’t going to come from a factory floor in Ohio.

If the traffic jam was going to be broken, the answer had to be found right there in the chaos of the field, using the junk lying around in the back of a truck.

Necessity is the mother of invention, they say.

But in war, desperation is the father.

And in a makeshift garage near the front, desperation was about to meet American ingenuity head‑on.

History often forgets that the line between a court‑martial and a Medal of Honor is razor thin.

Sometimes the only difference is whether your crazy idea actually works.

In a dripping‑wet canvas tent somewhere near the Belgian border, Tech Sergeant Miller was walking that line.

He wasn’t a scientist with a PhD. He was a grease monkey with busted knuckles and a bad attitude about walking in the mud.

He looked at the pile of broken SCR‑625 mine detectors in the corner. And then he looked at his Willys Jeep.

Two tools. One was too slow. The other was too fast.

But Miller realized something the brass back in Washington hadn’t.

The problem wasn’t the technology.

The problem was the delivery system. The problem was human legs.

“If we can’t *walk* the mines out,” Miller muttered to his corporal, “why don’t we *drive* them out?”

It sounded insane. Driving a Jeep into a minefield was literally the textbook definition of suicide.

But Miller had a vision. He didn’t see a car. He saw a platform.

The fabrication process that followed was pure, unfiltered American improvisation.

There were no blueprints. There were no safety inspections.

There was just a welding torch, a pile of scrap iron scavenged from a bombed‑out bridge, and a relentless desire to get the job done.

Miller and his crew went to work like mad scientists.

They took the delicate electronic guts out of the infantry mine detectors—the amplifier, the batteries, the search coil.

They weren’t treating this equipment with the proper respect the manual demanded. They were hacking it.

They grabbed lengths of angle iron and welded them to the front bumper of the Willys.

They weren’t building a bumper. They were building a boom—a massive, articulated arm that extended six to ten feet out in front of the vehicle’s nose.

It looked ridiculous. It looked like the Jeep was growing the antennae of a giant metal lobster.

But there was genius in the madness.

The logic was cold and hard. If the search coil was mounted directly to the bumper, the Jeep would trigger the mine at the exact moment it detected it.

Boom. Game over.

They needed standoff distance. They needed time.

By extending the sensor ten feet forward, they were buying the driver a fraction of a second.

That ten‑foot gap was the difference between life and death. It was the reaction zone.

The garage was filled with the acrid smell of ozone and burning metal. Sparks flew as they jury‑rigged the wiring.

They ran cables from the sensor on the boom back across the hood and into the dashboard.

They took the operator’s headset—usually worn by a guy crawling in the dirt—and modified it for the driver.

When they stepped back to look at their creation, it wasn’t pretty.

It was a Frankenstein monster of parts. Wires were duct‑taped to the fender. The boom bobbed up and down with the suspension.

It looked like a Rube Goldberg contraption that would fall apart at the first pothole.

A visiting officer reportedly walked past the tent, saw the monstrosity, and asked, “What in God’s name is *that* thing?”

Miller didn’t salute. He just wiped the grease from his forehead and patted the hood of the Willys.

“That, sir,” he said, “is the fastest minesweeper in the U.S. Army. Or it’s a very expensive coffin. We’re about to find out.”

They fired up the engine. The little Go‑Devil engine purred to life, vibrating the strange metal boom out front.

It was ugly. It was unauthorized. And it was untested.

But as it rolled out of the garage and into the gray light of dawn, it represented the very best of the American GI spirit.

If you don’t give us the tool we need, we’ll build it ourselves out of your junk.

Now all they had to do was find someone crazy enough to drive it.

We usually think of a safety feature as something that softens the blow—like a seat belt or a helmet.

But in Sergeant Miller’s garage, the ultimate safety feature wasn’t a piece of armor. It was a math problem.

And if you solved it wrong, you didn’t get an F. You got vaporized.

Let’s look under the hood of this mechanical Frankenstein.

To the untrained eye, it looked like a Jeep that had driven through a hardware store and dragged half the inventory out with it.

But every ugly weld and hanging wire served a brutal purpose.

The heart of the beast was the search coil ripped from the handheld detector.

But instead of swinging from a soldier’s tired arm, it was suspended inside a wooden or plastic housing, dangling from that long, skeletal boom extending from the front bumper.

The engineering challenge here was a nightmare.

The coil had to float in the sweet spot—close enough to the ground to sniff out the magnetic signature of a German mine, but high enough to clear rocks and debris.

Too high, you miss the mine and blow up. Too low, you hit a bump, break the sensor, and the convoy stops.

But the real magic—and the real terror—happened inside the cab.

Miller and his team didn’t just want a detector. They wanted a reflex.

They knew that a human driver, no matter how sharp, takes time to react.

The brain has to hear the signal, process the fear, and tell the foot to hit the brake. That takes about three‑quarters of a second.

At 5 mph, that’s a delay of roughly five feet. Five feet is the difference between stopping before the mine and stopping on top of it.

So they bypassed the human brain entirely.

In some of the most advanced field modifications, these mechanics rigged up a solenoid—an electrical switch scavenged from starter motors or aircraft parts—and connected it directly to the Jeep’s brake and clutch pedals.

Think about the genius of that for a second. This was 1944.

They didn’t have microchips. They didn’t have computers.

They built an automated braking system using copper wire and junk parts.

Here’s how the dance of death worked. The driver would creep forward, sweating bullets, moving at a steady walking pace.

The moment that search coil out front sensed metal, an electrical impulse shot back through the wires.

Before the driver could even blink, the solenoid would fire, slamming the clutch in and locking the brakes.

The Jeep would lurch to a violent halt, throwing the driver against the steering wheel.

It was crude. It was violent. But it was brilliant.

The machine reacted faster than the man.

Inside the cockpit, the driver still wore the headset, listening to the constant low‑frequency hum of the detector.

It was a sound that drilled into your skull. A steady hum meant life. A sharp rise in pitch meant metal.

But there was a catch. This system wasn’t perfect.

It couldn’t tell the difference between a jagged piece of shrapnel and a live Teller mine.

Every time the Jeep slammed to a halt, the driver had to get out, walk to the front, and stare at the ground beneath the sensor—praying that the metal object down there was just a rusty tin can.

It turned the Jeep into a divining rod for danger.

It was a marvel of adaptation, stripping the Willys of its primary asset—speed—and giving it a new superpower: foresight.

But all the solenoids and sensors in the world couldn’t change the fact that someone still had to sit in that driver’s seat, completely exposed, trusting their life to a gadget built from scrap metal.

And now it was time to see if the math actually held up in the mud.

There is a golden rule in military engineering: nothing ever works right the first time.

But when your prototype is a 2,000‑pound vehicle driving directly over high explosives, “back to the drawing board” usually means back to the morgue.

The proving ground wasn’t a safe, cordoned‑off test track in Michigan.

It was a muddy, cratered road leading into a town that the maps called “liberated,” but the scouts called a death trap.

Sergeant Miller didn’t ask a subordinate to drive. He didn’t order a private to play the guinea pig.

He climbed into the driver’s seat himself.

That’s the unwritten law of the mechanic: if you build the beast, you ride the beast.

He strapped the heavy headset over his ears, drowning out the murmurs of the infantrymen watching from the ditch.

To them, Miller looked like a dead man walking. They were taking bets on how far he would get—50 yards, 100?

The skepticism was thick enough to cut with a knife. To the brass, this was a circus act. To the grunts, it was a suicide run.

Miller shifted the Willys into low gear. The engine whined.

The ungainly wooden boom out front bobbed and weaved like a dowser’s rod hunting for water.

The world narrowed down to the space between his ears. All he could hear was the static hiss of the detector.

All he could see was that wooden frame hovering inches above the mud.

He was driving blind, trusting his life to a mess of wires he had taped together just hours ago.

Ten yards. Twenty yards. The Jeep crawled forward. The mud sucked at the tires.

Suddenly, the hiss in his ears spiked into a scream.

*SCREECH.*

Before Miller’s foot could even twitch, the solenoids fired. The brake pedal slammed to the floor with a mechanical violence that threw him forward against the steering wheel.

The Jeep skidded to a halt, rocking on its suspension. The engine stalled.

Silence. Absolute, terrifying silence.

Miller sat frozen.

His heart was hammering against his ribs like a trapped bird.

Had he stopped in time, or was the pressure plate already depressed, ticking down a delay fuse beneath his front tire?

The soldiers in the ditch held their breath. They waited for the pink mist. They waited for the thunder.

Nothing happened.

Slowly, shakily, Miller unhooked the door strap.

He stepped out into the mud, his boots sinking deep.

He walked to the front of the Jeep, past the radiator, past the bumper, out to where the sensor head hovered over a patch of disturbed earth.

He pulled a can of white spray paint from his belt.

He knelt down and carefully, ever so carefully, brushed away a layer of wet leaves.

There it was: the dull gray metal casing of a German Teller mine.

The sensor had caught it. The brakes had caught it.

And the front tire was sitting exactly three feet away from oblivion.

Miller sprayed a bright white X on the ground, stood up, and turned to the gallery of stunned faces in the ditch.

He didn’t smile. He didn’t cheer.

He just gave a thumbs‑up, climbed back into the Jeep, and started the engine.

The skepticism vanished instantly. A cheer went up from the infantry that could have drowned out an artillery barrage.

In that split second, the “lobster Jeep” graduated from a garage experiment to a savior.

The bottleneck was broken. The road was open.

And for the first time in weeks, the convoy wasn’t stopping for death.

It was stopping to mark it—and move on.

War is often remembered in broad strokes on a map.

We see arrows moving east, lines shifting west, and territories changing colors.

But for the men on the ground, the war wasn’t a map.

It was the ten feet of dirt directly in front of them.

And thanks to a grease‑stained mechanic and a hacked‑up Willys Jeep, that dirt was no longer a graveyard.

The lobster Jeep didn’t just clear a path through the Rhineland. It cleared a path through the psychological paralysis that had gripped the Army.

The design—crude, ugly, and brilliant—spread like a virus of hope.

From the frozen forests of the Ardennes to the sun‑baked roads of Italy, field workshops began replicating Sergeant Miller’s contraption.

They didn’t wait for official blueprints. They didn’t wait for permission.

They saw a problem, and they saw a solution that worked.

The Willys Jeep had always been called the Swiss Army knife of the war.

But this was its finest hour.

It ceased to be just a vehicle. It became a teammate.

It was the metal skin that bled so the soft flesh inside didn’t have to.

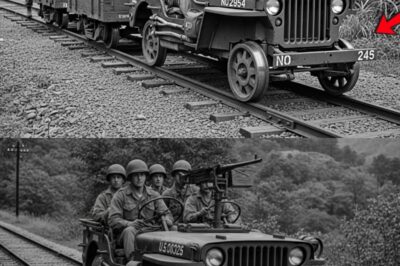

When we look at these black‑and‑white photos today, it’s easy to smile at the absurdity of it—a Jeep with a ten‑foot nose.

It looks like a cartoon. But zoom in.

Look at the faces of the men walking behind it.

They aren’t looking at the ground anymore. They are looking forward.

They are walking with heads high, rifles ready, marching toward victory instead of inching toward death.

That is the true legacy of American ingenuity.

It isn’t about the shiny, perfect weapons developed in sterile labs.

It is about the ability to look at a pile of junk in a muddy garage and see a way to save your brother’s life.

Most of these mine‑detecting Jeeps never made it back to the States.

They were driven until they broke, then stripped for parts and left to rust in the ditches of a continent they helped liberate.

There are no monuments to them.

You won’t find a bronze statue of a Jeep with a wooden boom in the town square.

But their monument is written in something far more permanent than bronze.

It is written in the family trees that continued to grow after 1945.

It is written in the lives of the soldiers who didn’t step on a pressure plate that autumn—who went home to marry their high school sweethearts, to raise children, and to build the world we live in today.

We often talk about “the road to victory.”

But we forget that the road had to be built inch by inch by men who were willing to drive into the unknown so others could follow in safety.

In the end, that little engine didn’t just open the road to Berlin.

It kept the road to the future open for all of us.

They built a machine to find death—

Only so they could find their way to life.

News

The US Army’s Tanks Were Dying Without Fuel — So a Mechanic Built a Lifeline Truck

In the chaotic symphony of war, there is one sound that terrifies a tanker more than the whistle of an…

Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her : “He Took a Bullet for Me!”

August 21st, 1945. A dirt track carved through the dense jungle of Luzon, Philippines. The war is over. The emperor…

The US Army Had No Locomotives in the Pacific in 1944 — So They Built The Railway Jeep

Picture this. It is 1944. You are deep in the steaming, suffocating jungles of Burma. The air is so thick…

Disabled German POWs Couldn’t Believe How Americans Treated Them

Fort Sam Houston, Texas. August 1943. The hospital train arrived at dawn, brakes screaming against steel, steam rising from the…

The Man Who Tried To Save Abraham Lincoln Killed His Own Wife

April 14th, 1865. The story begins with an invitation from President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary to attend a…

**“The Softest Secret of De Gaulle: The Disabled Daughter Who Changed a National Hero”**

Instead of hiding his daughter with Down syndrome, Charles de Gaulle raised her proudly, and she became the heart of…

End of content

No more pages to load