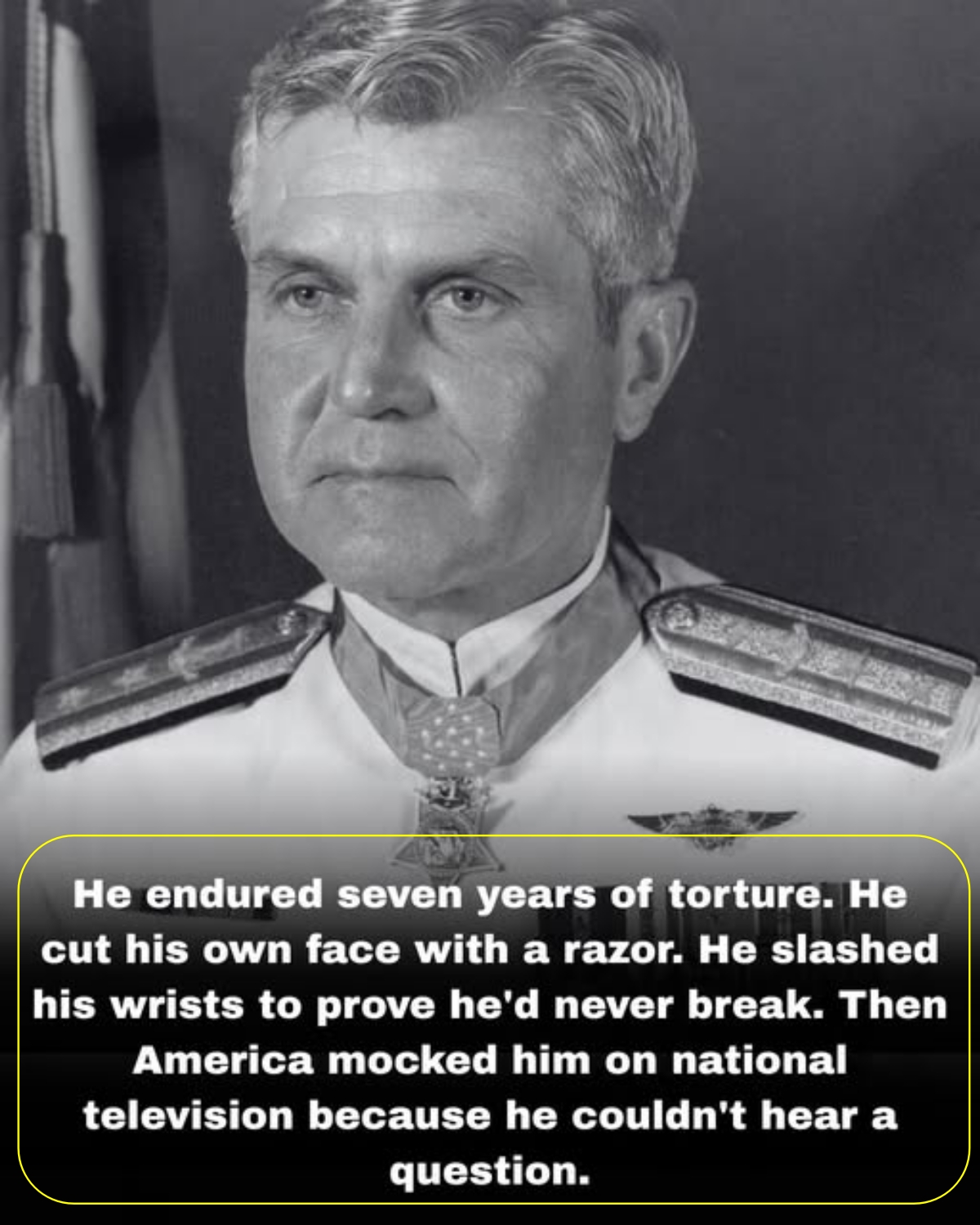

He endured seven years of torture. He cut his own face with a razor. He slashed his wrists to prove he’d never break.

Then America mocked him on national television because he couldn’t hear a question.

September 9, 1965. North Vietnam.

Captain James Stockdale was flying his A-4 Skyhawk over enemy territory when anti-aircraft fire tore through his plane. He ejected, and the fall shattered his back and dislocated his knee. He was captured within minutes.

North Vietnamese soldiers beat him until he could barely stand, then dragged him to Hỏa Lò Prison—the place American POWs would call the “Hanoi Hilton.” Stockdale had no idea he’d spend the next seven years there. At 41, he was the highest-ranking U.S. naval officer held prisoner in North Vietnam, and the enemy knew it. They decided to make an example of him.

He was a Naval Academy graduate with a master’s degree from Stanford. He was disciplined, intellectually sharp, and deeply principled. Over seven years, they tortured him fifteen times. They starved him, denied him medical treatment, and tried to break his will.

They kept him in solitary confinement for four years. They locked him in leg irons for two. He lived in a world of concrete walls, bare cells, and sudden eruptions of pain. But Stockdale refused to break.

He organized a secret communication system among the POWs—taps on walls, coded coughs, hand signals during brief moments outside cells. Through that system, he kept the men unified. He kept them alive. Most importantly, he kept them human.

Then came spring 1969. Stockdale learned the North Vietnamese planned to parade him and other POWs before foreign journalists—proof, they claimed, that prisoners were being treated well. He knew what that spectacle would mean.

His captors would force him to smile, to say he was being treated humanely, to become a living advertisement for the regime that was torturing him. Stockdale understood that if he cooperated, even under duress, his image would be used against his own country and his fellow prisoners. He couldn’t let that happen.

Late one night, he took a razor and slashed open his own scalp. Blood poured down his face and into his eyes. Then he grabbed a wooden stool and beat himself in the face with it—over and over—until his face was so swollen and disfigured that he couldn’t be presented to anyone.

The North Vietnamese found him like that and were enraged. They had planned their propaganda event; he had destroyed it with his own blood. As punishment, they tortured him again—more brutally than before, for days.

But they didn’t get their photo op. There was no clean, composed image of a healthy, smiling James Stockdale for foreign cameras. There was only a battered man who had literally disfigured himself rather than be used.

Later, when his captors discovered the secret communication network he’d organized among the POWs, they saw it as an act of rebellion. They tortured him again, determined to crush the resistance. This time, Stockdale decided to show them—once and for all—that he would never, ever submit.

He slashed his own wrists.

His Medal of Honor citation describes what happened next:

“He deliberately inflicted a near-mortal wound to his person in order to convince his captors of his willingness to give up his life rather than capitulate.” Stockdale was sending a message: they could not use him, could not own him, could not force him to betray others.

The North Vietnamese found him bleeding out. They revived him—not because they cared if he lived, but because a dead Stockdale was useless strategically. A corpse could not be paraded, interrogated, or exploited.

But something changed after that. They realized he meant it. He would die before he’d break. If they pushed him too far, they’d lose their most valuable prisoner—and the message that would send to other POWs terrified them.

The excessive torture stopped—not just for Stockdale, but for all the POWs. By proving he was willing to die on his own terms, he imposed limits on his captors. He had saved himself and his men by convincing the enemy that further brutality could backfire.

Seven years. Fifteen torture sessions. Four years alone in a cell. Two years in irons. The numbers are clinical; the reality was not. It was years of pain, isolation, and the constant temptation to give up.

February 1973. Operation Homecoming.

Stockdale was finally released. The torture had damaged him so severely he could barely walk. His hearing was destroyed—his eardrums ruptured from repeated beatings.

He came home to a hero’s welcome. In 1976, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He was already one of the most decorated officers in Navy history, and in 1979, he retired as a Vice Admiral.

After the Navy, he devoted himself to academia, teaching philosophy at Stanford. He reflected deeply on stoicism, duty, and resilience. Universities recognized his mind and his character—he received eleven honorary doctoral degrees.

And then, in 1992, something strange happened. His friend Ross Perot—who had worked tirelessly to help POWs during the war—decided to run for president as an independent. Perot asked Stockdale to stand in as his vice-presidential candidate temporarily, just until a permanent candidate could be found.

But a permanent candidate was never found. One week before the nationally televised vice-presidential debate, Stockdale learned he’d have to go on stage with Al Gore and Dan Quayle. He had no campaign machine, no media training, and almost no preparation.

Admiral James Stockdale was no politician. He was a warrior, a philosopher, and a survivor of unimaginable horror. On October 13, 1992, he stood on that debate stage—out of place, uncomfortable, and unpolished, but willing to serve because a friend had asked.

When the first question was directed to him, he didn’t hear it. His hearing aids—the ones he needed because his captors had destroyed his eardrums—weren’t turned on. He fumbled, apologized, and tried to regain his footing.

“I forgot to turn on my hearing aid,” he said. It was a simple, human mistake—a technical slip from a man whose body carried the scars of years of torture.

America laughed.

Late-night comedians made him a punchline. Sketch shows turned him into a caricature: the confused old man who couldn’t hear, who didn’t belong on stage, who seemed lost and doddering. “Stockdale” became slang for an out-of-touch fool.

The man who had mutilated himself rather than be used as propaganda. The man who had saved dozens of lives with his courage. The man who had endured seven years of hell.

He was mocked on national television by millions of people who had no idea what he’d sacrificed. They saw a momentary stumble, not the long, brutal road that led to it.

Two years later, comedian Dennis Miller said this on his HBO show:

“Now I know ‘Stockdale’ has become a buzzword in this culture for doddering old man, but let’s look at the record, folks. The guy was the first guy in and the last guy out of Vietnam, a war that many Americans, including your new President, chose not to dirty their hands with. He had to turn his hearing aid on at that debate because those fucking animals knocked his eardrums out when he wouldn’t spill his guts. He teaches philosophy at Stanford University. He’s a brilliant, sensitive, courageous man. And yet he committed the one unpardonable sin in our culture: he was bad on television.”

Miller was right. In a culture that worships performance, Stockdale’s real achievements were invisible. He had survived torture that would have broken almost anyone. He had organized resistance from inside a prison cell.

He had disfigured himself to deny his enemies a propaganda victory. He had nearly bled to death to prove he’d never surrender. And America remembered him as the guy who forgot to turn on his hearing aid.

Vice Admiral James Bond Stockdale died in July 2005 at age 81, after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease. His body and mind had carried the cost of his service for decades. Even in illness, he was surrounded by a family who knew the truth of his life.

He was born in Abingdon, Illinois, on December 23, 1923—one hundred two years ago today. His story began in a small Midwestern town and carried him through war, captivity, and public misunderstanding.

His wife Sybil—who fought for POWs relentlessly while he was imprisoned—was a hero too. She launched a national awareness campaign, refused to accept silence, and changed how America treated its prisoners of war. She died in 2015, having spent her life fighting for men the world could not see.

History should remember James Stockdale for what he endured. For what he sacrificed. For the men he saved and the example he set. Not for a hearing aid malfunction on a debate stage.

He cut his own face to avoid being propaganda. He slashed his own wrists to prove he’d never break. He survived seven years in hell.

And when he came home, he was mocked for the injuries his torture had caused. That’s not justice. But it is a reminder.

Sometimes the people who sacrifice the most are the ones we forget first. Sometimes the heroes who endure the worst are the ones we turn into punchlines. James Stockdale deserved better.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load