San Francisco, 1872.

A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built railroads, banks, and empires. Women were expected to build something else: families, reputations, quiet lives that didn’t threaten anyone’s idea of how the world should work.

In that city, in that year, a girl named Julia Morgan was born.

From the beginning, the rules were clear. Women could sew, teach, perform music, host guests. They could be graceful, refined, obedient. They were *not* supposed to be out on construction sites, arguing with contractors, calculating loads, or designing towers that could withstand the anger of the earth itself.

Building things was not on the approved list.

Julia did not care.

The Girl Who Liked to Look Up

Imagine her as a child in San Francisco, walking past buildings that scratched at the sky. Most people noticed the signs, the crowds, the noise. Julia noticed lines. Angles. How the light hit a cornice at 3 PM. How a building met the ground. How a staircase carried weight.

Her family was comfortable, not poor and not fabulously rich—secure enough that she had access to education and books. Her mother gave her music lessons, as a proper young lady should have. Her father, a businessman and engineer, talked about structures, bridges, and numbers.

Someone else might have absorbed those conversations politely and then gone back to embroidery. Julia listened and filed them away.

In a world that told girls to look down, she kept looking up.

Berkeley: The Only Woman in the Room

At 18, when many young women of her time were thinking about marriage, Julia was thinking about math, stress loads, and structural integrity. She enrolled at UC Berkeley to study civil engineering. Not finishing school. Not literature. Not music. Engineering.

She walked into lecture halls and seminar rooms filled with men. Dozens of them. Sometimes hundreds. She was often the only woman in the room.

You can picture the looks. Some curious. Some dismissive. Some amused. One girl among all these serious young men, training to become builders of the modern world.

Did they say anything to her? Some surely did. Comments like:

– “Shouldn’t you be in the arts department?”

– “Are you lost?”

– “You know this is engineering, right?”

But if that bothered her, she didn’t leave. She stayed. Day after day. Year after year.

She solved the same problems. Took the same tests. Studied the same diagrams. If anything, she had to be *better*, because one mistake would be blamed not just on “Julia,” but on “women.”

In 1894, she graduated. The only woman in her engineering class. No shortcuts. No extra accommodations. Just work.

A Mentor with an Impossible Suggestion

At Berkeley, one of her professors saw something in her that went beyond good grades. A seriousness. An obsession. A calm, focused intensity.

He knew she was drawn not just to the math of structures but to the *art* of them: proportion, composition, beauty. So he suggested something outrageous.

Apply to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

To understand how impossible this sounded, you have to understand what that school was. The École des Beaux-Arts was not just an architecture school. It was *the* architecture school. The elite of the elite. The place where the great designers of Europe sharpened their tools.

And in all its history, up to that point, it had never admitted a woman to study architecture.

Not once.

Not ever.

Her mentor knew this. Julia knew it. The whole world knew it.

But he still told her to try.

He might as well have said, “You should try being the first person to walk on the moon.”

Most people, confronted with that, would have laughed, thanked him politely, and gone home to find a more “realistic” plan. Julia packed her bags.

Paris: A Closed Door, Slightly Open

She arrived in Paris in the late 1890s. A city of boulevards, cafés, and seriousness about art. She took drawing classes, brushed up her skills, and waited.

In 1897, after years of pressure from French women artists, the École finally made a concession. It would allow women to apply to the architecture program.

Apply. Not attend.

There was still a gate. That gate was the entrance exam.

Julia took it. It was brutal—multi‑day, highly competitive, designed to filter out all but the very best. She poured herself into it, submitted her drawings, her plans, her solutions. Then she waited for the rankings.

She placed 42nd out of 376 applicants.

Only the top 30 were accepted.

That number—42—could have been a life sentence. She had done well. Better than hundreds of men. But “well” wasn’t enough. She was out.

She tried again six months later. Another round of effort. Another exam. Another hope. This time, she failed again.

Some people later speculated that the jury deliberately lowered her scores because she was a woman. They didn’t need to say it out loud. Bias rarely announces itself. It just quietly moves the line a few inches out of reach.

Twice rejected. Twice close, but not enough.

Most people would have taken this as a sign. A message from the universe: this path is not for you.

The Third Attempt

Julia took the exam a third time.

Think about what that means. Not just stubbornness. Not just optimism. It means she believed something most of the world did not:

– That she did belong there.

– That her work was good enough.

– That a rule that had never been broken before could be broken with *her* name on it.

She sat down for the exam again. Pencil. Paper. Hours of concentration. She drew, calculated, composed. Every line had weight. Every decision mattered.

This time, when the results were posted, they told a different story.

Out of 392 applicants, she placed 13th.

Not barely in. Not squeaking by the cutoff. Safely inside. The École des Beaux-Arts had no excuse left. They couldn’t hide behind rankings or “merit.” By their own criteria, she had earned a place.

They admitted her. She became the first woman ever accepted into their architecture program.

The door that had been closed to women for generations didn’t swing wide open for everyone. It opened just enough for one determined woman to squeeze through.

On the Clock

There was a catch. There is almost always a catch.

Students at the École had to finish their studies and graduate before turning 30. This wasn’t a flexible guideline. It was a rule. And Julia was already 25.

She had less than five years to complete a program that many men took significantly longer to finish. That meant no wasted time. No failing out. No do‑overs.

So she did what she had always done: she worked. Hard. Quietly. Relentlessly.

No one writes about her partying through Paris. No one tells stories about dramatic romances or scandals. What we know about those years is simple: she produced. Project after project. Design after design. Critique after critique.

Architecture, at that level, is not a casual discipline. It’s long nights, rewrites, corrections. It’s professors tearing apart your designs and forcing you to defend every line. It’s walking through the city, sketchbook in hand, trying to understand why a façade feels “right.”

Julia wasn’t just surviving that environment. She was excelling.

In February 1902, one month before her 30th birthday, she did what no woman had ever done. She earned her certificate in architecture from the École des Beaux‑Arts.

There was no parade. No fireworks. No headline: *Woman Does the Impossible*. The world moved on, as it always does.

But a fact had been created. A barrier that had existed for centuries was no longer absolute. A woman had walked in, done the work, and walked out with the same qualification as the men.

Back Home: Talent, With a Discount

Armed with a world‑class education, Julia returned to California. She did not walk into a world that suddenly respected her.

She went to work for an established architect. He praised her talent to colleagues. He bragged about her training. He liked having someone so capable in the office.

And then, when it came time to talk about money, he revealed how he really saw her. He told another architect he could pay her “almost nothing, as it is a woman.”

He didn’t whisper it. He didn’t hide it. To him, this was reasonable. Logical, even. Same work, lower cost. Why not?

Julia overheard.

Imagine that moment. You’ve fought your way through a male‑dominated university in America. You’ve crossed an ocean. You’ve broken into the most prestigious architecture school in the world. You’ve worked yourself to the edge of exhaustion to graduate on time.

And now, back home, someone tells you your work is worth “almost nothing” because of your gender.

She could have shouted. She could have cried. She could have thrown her drafting tools at the wall. We don’t have a record that she did any of those things.

What we know is this: she listened. She learned. And she quietly made a different plan.

She saved her money. She waited until the time was right. And then she quit.

1904: The License, the Office, the Leap

In 1904, Julia Morgan became the first woman licensed as an architect in California.

There was no special category, no “women’s license.” She passed the same exams as everyone else. Her name went onto the same list. Her stamp carried the same legal weight.

Then she did something even more radical: she opened her own office in San Francisco.

She wasn’t content to be the underpaid genius in the corner of someone else’s firm. She was going to put her own name on the door, sign her own drawings, and answer to her own clients.

She rented space. She set up her drafting tables. She hired staff. She began to build something that hadn’t existed before: a woman‑led architecture practice in a world that barely believed such a thing was possible.

The first projects came slowly. Word of mouth. Smaller commissions. Clients who were willing to take a chance—or who were smart enough to see that “chance” wasn’t the right word.

Then, at 5:12 AM on April 18, 1906, the ground moved.

The Earthquake

San Francisco shook itself apart.

A massive earthquake ripped through the city. Gas lines burst. Fires spread. Wooden buildings snapped. Brick façades peeled off like scabs. The shaking lasted less than a minute. The burning lasted for days.

Over 3,000 people died. Nearly 80% of the city was destroyed.

The skyline changed in a week.

Across the bay at Mills College in Oakland stood a bell tower. 72 feet of reinforced concrete that Julia had designed. Slender, elegant, and, as some critics thought at the time, perhaps too daring.

When the ground finished screaming and the dust settled, many buildings were cracked, broken, or gone.

Her bell tower stood.

Not just *mostly* standing. Standing, unscathed. Straight. Intact. Functional.

It wasn’t luck. It was design. She had used reinforced concrete—still relatively new in American architecture at the time—and used it intelligently. She had calculated loads and stresses with the eye of an engineer and the instinct of an artist.

People noticed.

In a city desperate to rebuild, suddenly there was proof. This woman could design structures that didn’t just look beautiful; they *survived*.

Clients flooded her office.

Rebuilding a City

One of the most symbolic buildings in San Francisco was the Fairmont Hotel. Elegant, imposing, perched on Nob Hill like a statement of wealth and stability. After the earthquake and the fires, its exterior still stood, but its interior was gutted—burned and ruined.

The owners needed someone to rebuild it. Someone fast, competent, and fearless. They hired Julia Morgan.

Under enormous pressure, she redesigned and oversaw the reconstruction. In less than a year, the Fairmont reopened. It became, once again, a symbol—this time of resilience and rebirth.

People walked through its halls, slept in its rooms, looked at its details, and most of them never knew a woman had made it possible.

That was a pattern throughout her career. She did enormous work with very little self‑promotion. No giant signature stamped on the façade. No loud interviews. The buildings spoke for her.

A Life of Work, Not Fame

Over the decades that followed, Julia’s office rarely sat idle. She designed:

– More than 30 YWCA buildings across multiple states—spaces specifically intended to support and shelter women.

– Churches that anchored communities.

– Schools that held generations of students.

– Hospitals where lives were saved.

– Offices, theaters, private homes.

– And, most famously, a sprawling project on a hill above the California coast: Hearst Castle.

Hearst Castle was not just one building. It was a complex of structures, gardens, pools, terraces, and details. Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst had money, ambition, and a vision. Julia had the discipline and imagination to turn that vision into reality.

For 28 years, she worked on that property.

Twenty‑eight years of drawings, revisions, supervision, decisions. Every tile, every arch, every column had to be not just beautiful but *buildable*. She walked the site. She managed crews. She adapted to changing whims and realities.

All this, while continuing to run her practice and serve other clients.

By the time she retired in 1951, the numbers were staggering. She had designed more than 700 buildings.

Seven hundred. In an era when people were still debating whether women should be allowed to vote, she was shaping skylines.

After the Work: The Quiet Fade

You might expect that when she died in 1957 at age 85, the obituaries would be long and loud. You might expect the profession to stop and reflect on what she had done.

Some did. Many didn’t.

Architecture, as a field, has a long tradition of forgetting the people who don’t match its preferred image of “the great architect.” For decades, her name faded from public attention.

Her buildings stood. People lived in them, prayed in them, learned in them, healed in them. Kids ran through hallways she had drawn on tracing paper decades before.

But the hand behind those lines was rarely mentioned.

The world moved on to new styles, new stars, new “masters.”

Rediscovery

Then, in 1988—more than 30 years after her death—a biography pulled her back into the light.

Researchers dug into archives. Historians traced projects. Old photos, letters, and drawings resurfaced. Patterns emerged.

This wasn’t just a talented architect among many. This was a foundational figure. Someone who had fully integrated engineering and art. Someone who had quietly redefined what was possible for women in her field.

Her story spread. Architecture schools began teaching her work. Scholars wrote articles. Tours highlighted “Julia Morgan buildings.” People started to see something that had been hiding in plain sight.

In 2014—57 years after she died—the American Institute of Architects awarded her the AIA Gold Medal, their highest honor.

Until that year, every recipient had been a man.

Julia Morgan became the first woman ever to receive it.

She did not stand on the stage to accept it. There was no speech. But the award said what the world had been slow to admit:

She belonged in the pantheon. She always had.

What She Did—and What She Didn’t Do

Look back at her life with clear eyes:

– She was told no, over and over.

– She was underpaid.

– She was underestimated.

– She worked in an era when women were not supposed to design buildings, negotiate with contractors, or lead offices—let alone design more than 700 structures.

She did not launch public campaigns demanding respect. She did not make herself the story. She did not wait for the world to become fair.

She just built.

She built in exam rooms in Paris, on drafting tables in San Francisco, on hillsides above the Pacific, in towns and cities up and down the coast.

She built when people questioned her presence.

She built when people discounted her pay.

She built when her name was left out of the articles.

And what she built is still standing.

Why Her Story Matters Now

It’s tempting to look at stories like Julia Morgan’s as ancient history. To say, “Things are different now,” and move on. And yes—some things *are* different. Women can study architecture openly. Many countries have laws against pay discrimination. Doors that were nailed shut are, at least in theory, open.

But some things haven’t changed as much as we’d like to think:

– People are still told “this field isn’t for you.”

– Bias still nudges scores down a few invisible points.

– Talent is still discounted because of gender, race, age, or class.

– Quiet workers still get overlooked while louder names get credit.

That’s why her story hits so hard. Because it isn’t just about architecture. It’s about anyone who has ever been told, directly or indirectly, “You don’t belong here.”

Julia Morgan’s answer was not a speech. It was a career.

She didn’t wait for permission.

She didn’t wait for everyone to be comfortable.

She didn’t wait for the world to be ready.

She built.

If the system pushed her out, she pushed back in by being too good to ignore. If they paid her “almost nothing,” she left and built a business where she set the terms.

When the ground shook and buildings fell, hers stayed standing—and people noticed.

The Quiet Revolution

Not all revolutions are loud. Some look like this:

– A young woman sitting alone in a lecture hall full of men and not leaving.

– A rejected candidate taking the same brutal exam a third time instead of accepting the verdict.

– An underpaid employee quietly saving, then walking out to start her own firm.

– An architect choosing reinforced concrete and careful detailing so her tower will survive when others fall.

Julia Morgan’s revolution wasn’t in slogans. It was in drawings, calculations, contracts, and concrete.

It was in the simple, stubborn decision to keep doing the work at a level that made arguments against her look ridiculous.

She lived in a time that had very clear ideas about what women could and couldn’t do.

Building things was not on the approved list.

She built anyway.

News

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid….

“Is This Pig Food?” – German Women POWs Shocked by American Corn… Until One Bite

April 1945, a muddy prison camp near Koblenz, Germany. Thirty‑four German women sat on wooden benches. Their uniforms were torn,…

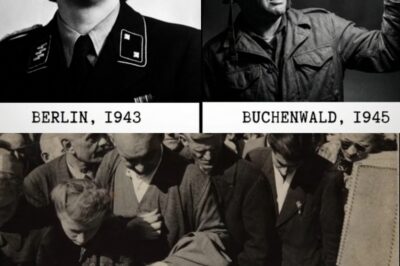

What American Soldiers Found in the Bedroom of the “Witch of Buchenwald”

April 13th, 1945. The outskirts of Weimar, Germany. A beautiful, sunny spring day. A group of American soldiers from the…

End of content

No more pages to load