November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black smoke pours from the cowling of his P-51 Mustang. The Merlin engine screams—metal grinding against metal. Thirty seconds ago, he was leading a strafing run against a German airfield. Now he’s a dead man flying.

An 88 mm fragment has severed the oil line. Without oil, the Rolls-Royce Merlin will seize in roughly 90 seconds. After that, the prop becomes a 400-pound anchor and the Mustang turns into a brick with wings. Carr has one option: bail out. He slides the canopy, rolls the dying fighter inverted, and drops into the freezing sky.

At 8,000 feet, the silk canopy blooms. Below him, enemy territory stretches to every horizon—200 miles behind German lines. No radio, no weapon beyond a .45 pistol with seven rounds, no food, no water. November cold will fall below freezing at night. The math of survival is brutal: only 23% of downed pilots evade capture; 77% end up in Stalag Luft III or unmarked graves.

Bruce Carr is about to become the exception. In four days, he won’t just escape—he will steal one of Germany’s most advanced fighters and fly it home. Bruce Ward Carr was born January 28, 1924, in Union Springs, New York. Nothing about his childhood was remarkable except one thing: at 15, in 1939, he learned to fly.

The year matters. Germany invaded Poland that September; World War II began. A farm kid couldn’t know he’d be dogfighting over Berlin in five years, but something in him sensed that flying would become the most important skill a young man could possess. Not in a formal program—just a crop-duster named Earl letting him take the controls of a biplane one summer afternoon.

Carr was hooked. By 16, he had more stick time than most cadets. On September 3, 1942, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces at 18. In training, his instructor turned out to be Earl—who had joined up and now recommended Carr for the accelerated program after seeing 240 hours already logged.

By August 1943, Carr was a flight officer. By February 1944, he was in England with the 380th Fighter Squadron, 363rd Group, Ninth Air Force. His first assignment: the P-51 Mustang. The P-51 was the finest piston fighter ever built. Range 1,650 miles with drop tanks—enough to escort bombers from England to Berlin and back.

Top speed 437 mph at 25,000 feet. Ceiling 41,900 feet. Six .50 caliber Brownings with 1,880 rounds—enough to shred a bomber in two seconds. Before P-51Ds arrived in numbers, daylight raids suffered catastrophic losses—60 bombers lost over Schweinfurt in October 1943. Without escort, B-17s and B-24s were sitting ducks.

The Mustang changed everything. For the first time, American fighters could accompany bombers all the way. German pilots called them “long-nosed bastards.” The Luftwaffe bled experienced pilots faster than they could replace them. Carr fell in love immediately. The cockpit fit like a glove; controls were crisp; visibility excellent; power intoxicating. He named his plane Angel’s Playmate—never imagining he would soon sit in a cockpit with German labels and a swastika on the tail.

March 8, 1944: Carr’s first combat engagement. He chased a Bf 109 over Germany as the enemy dove for the deck, skimming treetops. Carr followed—forty miles at over 400 mph, both aircraft barely clearing the forest. His first bursts missed. A single bullet clipped the 109’s left wing; the pilot panicked and pulled up to bail out—too low. The chute didn’t fully deploy. The pilot hit at 60 mph; the 109 plowed into a hillside.

Carr returned expecting congratulations. Instead, his CO scolded him for reckless flying and transferred him. The kill didn’t count; the pilot had killed himself trying to escape. It was a signal that Carr didn’t think like others—where they saw recklessness, he saw opportunity; where they saw limits, he saw suggestions.

In May 1944, Carr transferred to the 353rd Squadron, 354th Group—the Pioneer Mustang Group, first in Europe to fly P-51s in combat. The best Mustang pilots in the war. Carr fit right in. June 17, 1944—eleven days after D-Day—he shared an FW 190 kill over Normandy. Two months later, he pinned second lieutenant.

September 12, 1944: strafing a German airfield, he destroyed several Ju 88s on the ground. On the way home, he spotted thirty FW 190s two thousand feet below. He dove. In three minutes, he shot down three fighters. When his wingman took damage, Carr escorted him back to friendly territory, foregoing more kills to protect him—earning the Silver Star.

October 29, 1944: two Bf 109s down over Germany. Total confirmed 7.5—officially an ace. Four days later, his luck ran out. November 2: he hit the frozen ground hard. The chute landing twisted his ankle—badly sprained. He buried the canopy silk under leaves. The Germans would search—he had twenty minutes.

He knew the airfield he had strafed lay five miles north. The Germans would expect him to move south or west. His survival depended on doing the unexpected. He headed north—toward the enemy. Counterintuitive, but logical: searchers would fan outward assuming escape; they wouldn’t expect him to move closer to the base. The airfield had food, water, and weapons.

Day one: forest movement at night; off roads; minimal warmth in the flight suit; ankle throbbing; 18 hours without food. Day two: a stream—ice-cold water numbing his throat. A German patrol 200 yards away; Carr lay motionless in a ditch for two hours while they passed. Day three: hunger became impossible; burning 4,000 calories just to stay warm; zero intake; his body cannibalized muscle. He decided to surrender at dawn.

Aviators treated aviators better; Stalag Luft camps were survivable—boring, but food, Red Cross packages, letters. Better than starving in a forest. Day four, late afternoon: Carr reached the edge of the airfield—eastern perimeter, treeline vantage. Hangars, fuel trucks, aircraft—FW 190s and some Bf 109s. He planned to walk to the gate at sunrise and surrender.

As darkness fell, he noticed a revetment 80 yards away. An FW 190 sat under camouflage netting. Two mechanics worked under portable lights. Carr watched. They checked fuel—full tanks. They ran the engine—the BMW 801 radial roared. Magnetos cycled. The preflight seemed complete. They shut down, covered the cockpit, and walked off. The FW 190 was ready to fly.

Carr’s mind started calculating. He’d never flown a German aircraft, didn’t speak the language, didn’t know the controls, starter, or gear—but he knew how to fly. Over 500 combat hours. Every aircraft has throttle, stick, and rudder. Physics don’t change because labels are in Gothic script. And a fully fueled fighter sat unguarded. The surrender plan evaporated.

At 3:00 a.m., the field fell quiet—skeleton watch, no activity near the revetment. Carr moved—eighty yards of open ground, no cover; if anyone looked, he died. He covered the distance in forty seconds, low and fast, his ankle screaming. The FW 190 was larger than expected—34-foot wingspan, 29-foot length, 7,000-pound empty weight, nearly a ton heavier than a P-51.

The cockpit sat high behind 30 mm armored glass. The BMW 801—14-cylinder air-cooled radial—made 1,700 horsepower. The FW 190 was Germany’s premier fighter—deployed in 1941, outclassed the Spitfire so thoroughly Britain rushed new variants. Germans called it “Würger”—Butcher Bird. Allies called it Trouble. Carr likely faced an A-8—two 13 mm guns in the cowling, four 20 mm cannons in the wings, 408 mph top speed, ~500-mile range.

Carr had never seen one from the inside. Everything he knew came from gun camera footage of them exploding. He slid the canopy and dropped into the cockpit. First problem: he couldn’t read anything. Every gauge and label was German. Second: the cockpit was tighter than the Mustang; his knees pressed the panel. The stick fell naturally to his right hand; throttle on the left—some things were universal.

He had four hours until sunrise. He used every minute—tracing wires, identifying gauges by position. Airspeed top-left. Altimeter top-center. Engine instruments clustered right. Fuel selector, magnetos, prop control—found. The starter was critical. In a Mustang, it’s electric. In an FW 190—unknown. On the right side, he found a T-handle with German text vaguely resembling “Starter.”

He pulled—nothing. He pushed—the cockpit filled with mechanical whine. An inertia starter winding. He let it spin—ten seconds, twenty. He pulled. The BMW coughed, caught, and roared to life. The noise was apocalyptic. Every German on the field would hear it. Carr had seconds.

No time for a runway or checks—no brakes, flaps, or radio. He shoved the throttle forward. The FW 190 lurched; the tail came up immediately—nose-heavy, eager to fly. He aimed between two hangars. Ground crews poured out, shouting and pointing. Sixty, seventy mph—the hangars rushed toward him. At ninety, he pulled. The FW 190 leapt, clearing roofs by inches.

Airborne in a stolen German fighter, 200 miles behind enemy lines. Now the hard part. Carr solved problems one at a time. Landing gear—left console lever—pulled. A satisfying thunk; the gear retracted. Speed built. Compass—gyro found; he oriented west-southwest toward France. Altitude—he climbed to 500 feet, then dropped back. Higher meant radar, fighters, flak. At treetop level, 50 feet and 280 mph, the forest blurred; radar missed him; flak couldn’t reach; ground troops couldn’t track.

Fuel showed full; ~500-mile range; France ~200 miles away—margin. For 45 minutes, he flew west. The sun rose. Forest gave way to farmland and scarred battlefields. He crossed the front—and his problems multiplied. Allied gunners saw what they expected: a German FW 190 at low altitude heading toward them. They opened fire.

Tracers arced from every direction. He had no radio, no signal—German markings on wings and tail. Carr flew lower and faster—down to 20 feet, hedgehopping. Prop wash kicked dust; civilians dove into ditches; American soldiers fired rifles. “Every .50 caliber in existence shot at me,” he later joked. Impacts shuddered the airframe, but German engineering held.

Ahead lay A-66—Orconte, France—home of the 354th. He lined up—no pattern, no calls—the flak crews already tracking him. Final problem: the gear wouldn’t come down. He pulled the lever—nothing. Pumped—nothing. Searched for an emergency release—unknown. The FW 190’s hydraulics required a selector valve to direct pressure to extension; he was pulling the wrong control.

Below, 40 mm Bofors crews loaded. A German fighter circled their base; they prepared to shoot it down. Carr decided to belly land. He lined up on grass beside the runway, lowered flaps—he had found that lever—and chopped throttle. The FW 190 sank—100 feet, 50, 20. It hit at 90 mph, slid 300 yards, flinging mud and debris, and stopped. Carr was alive.

Within seconds, MPs surrounded the aircraft—rifles raised—expecting a German. The canopy slid back. A mud-splattered American in a torn flight suit climbed onto the wing. “I’m Captain Carr of this goddamn squadron,” he shouted. No one believed him—missing four days, presumed dead or captured—and he had just belly-landed a German fighter on their field. Rifles stayed up until a staff car arrived.

Colonel George Bickel, CO of the 354th, stepped out, surveyed the wrecked FW 190, the mud-covered pilot, the bewildered MPs. “Where the hell have you been, and what have you been doing now?” The story blazed through the Air Forces—the only American in Europe to take off in a P-51 and return in an FW 190.

Carr’s war didn’t end there. April 2, 1945—near Schweinfurt—First Lieutenant Carr led four P-51s on reconnaissance at 15,000 feet. Movement above—German fighters stacked from 18,000 to 25,000—Bf 109s and FW 190s. He estimated 60 aircraft—the largest concentration he’d seen. Standard tactics said disengage. Four against sixty was suicide.

The Germans had altitude, numbers, and position. Manuals said report and live. Carr keyed his radio: “Engaging.” His wingmen didn’t hesitate. They climbed into the formation. The Germans weren’t expecting attack—loose defensive posture, conserving fuel, likely heading to intercept bombers. Four Americans climbing into their midst made no sense.

Carr used the confusion—slipped behind a Bf 109 and fired. The pilot never saw him; the 109 exploded. He shifted to an FW 190—three seconds of .50 caliber; the Butcher Bird rolled inverted and plunged. The formation scattered—no one knew how many attackers or where the fire came from. Carr moved through them like a wolf among sheep—picking, firing, moving. Third, fourth, fifth kills—three minutes, five aircraft down.

His wingmen accounted for ten more. Four Americans, fifteen German fighters destroyed, zero losses. Ammunition spent, Carr led his flight home. The surviving forty-five scattered. On April 9, Bruce Carr was promoted to captain and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross—second only to the Medal of Honor—for April 2.

His citation read: “Completely disregarding his personal safety and the enemy’s overwhelming numerical superiority and tactical advantage of altitude, he led his element in a direct attack … personally destroying five enemy aircraft and damaging another.” He became the last “ace in a day” in the European theater. No American matched that feat before Germany surrendered.

By war’s end, Carr had flown 172 combat missions and logged 14 or 15 confirmed aerial victories—records differ—plus numerous ground kills. He was 21. He stayed in uniform—joining the Acrojets, America’s first jet aerobatic team, flying F-80 Shooting Stars. In Korea, he flew 57 combat missions in F-86 Sabres with the 336th Fighter Interceptor Squadron—later commanding the 336th in 1955–56.

Then Vietnam—Colonel Carr, 44, flew 286 combat missions in F-100 Super Sabres—close air support, bombing, strafing—work he’d done 24 years earlier in a different war and aircraft. Three wars, three generations of fighters, 505 combat missions total. He retired in 1973.

April 25, 1998—St. Cloud, Florida—Bruce Ward Carr died of prostate cancer at 74. He was buried at Arlington—Section 64, Grave 6922—among heroes of every American war, within sight of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, across the river from the Lincoln Memorial. His headstone lists Colonel, USAF; Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, DFC with clusters, Air Medal with clusters, Purple Heart; and his wars—WWII, Korea, Vietnam.

It doesn’t mention the Butcher Bird, the four days in the Czechoslovakian forest, the belly landing with no gear, MPs pointing rifles, the CO asking, “Where the hell have you been?” Some stories don’t fit on stone. There are two ways to tell Bruce Carr’s story. The legend: the downed pilot who stole a German fighter and flew it home while every gun in Europe shot at him.

The record: the ace with 15 kills, Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross—the man who led four against sixty and won. Both are true; both are remarkable. But here’s what matters. In November 1944, an American pilot found himself alone, unarmed, and stranded 200 miles behind enemy lines. The rational choice was surrender. The safe choice was giving up.

Carr chose differently. He looked at an unfamiliar cockpit and saw not an obstacle, but an opportunity. He started an engine he’d never operated and flew an aircraft he’d never touched—not because he was reckless, but because he refused to accept that his options were limited to what seemed possible. Four months later, faced with sixty enemy fighters, he made the same calculation. Manuals said retreat. He chose attack. Fifteen enemy pilots never made it home.

In 1997, a year before his death, Colonel Carr flew once more. At Fantasy of Flight in Florida, he arrived in a P-51D—his own, still airworthy. He came over the crowd at 300 knots, 50 feet off the deck—the same profile he’d used fifty years earlier, flying a stolen FW 190 into a French airfield while his own side tried to shoot him down. Some things never change.

The crowd watched a 73-year-old man throw a WWII fighter through maneuvers that challenged pilots half his age—loops, rolls, high-G turns that would gray out younger men. Asked what he was thinking up there, he shrugged. “Same thing I was always thinking. What’s the airplane capable of? What am I capable of? Let’s find out.”

That’s the Bruce Carr story. Not just the stolen fighter or the 15 kills or three wars and 505 combat missions. It’s simpler. A pilot who looked at impossible odds and asked: What else can I do?

News

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

– Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying German prisoners slowed at Camp Ruston as nineteen women pressed their faces against…

Japanese Kamikaze Pilots Were Shocked by America’s Proximity Fuzes

-April 6, 1945. Off Okinawa in the East China Sea, dawn breaks over Task Force 58 of the U.S. Fifth…

When This B-26 Flew Over Japan’s Carrier Deck — Japanese Couldn’t Fire a Single Shot

At 7:10 a.m. on June 4, 1942, First Lieutenant James Muri dropped to 200 feet above the Pacific, watching thirty…

Why British Carriers Terrified Japanese Pilots More Than the Mighty U.S. Fleet

April 6, 1945. A Japanese Zero screams through the morning sky at 400 mph. The pilot, Lieutenant Kenji Yamamoto, has…

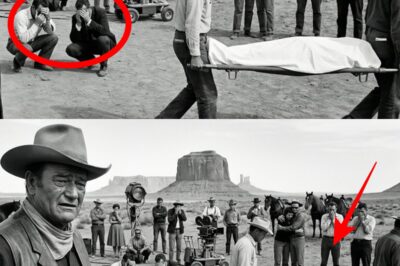

A Stuntman Died on John Wayne’s Set—What the Studio Offered His Widow Was an Insult

October 1966. A stuntman dies on John Wayne’s set. The studio’s offer to his widow is an insult. Wayne hears…

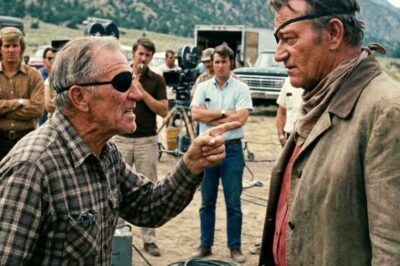

The Day John Wayne Met the Real Rooster Cogburn

March 1969. A one-eyed veteran storms onto John Wayne’s film set—furious, convinced Hollywood is mocking men like him. What happens…

End of content

No more pages to load