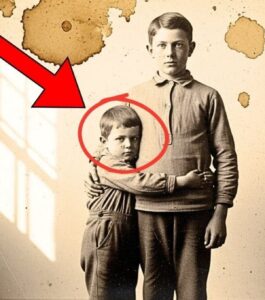

On October 15, 1895, photographer Marcus Webb was hired by the Blackwood Workhouse in Lancaster, England to showcase its “excellent” care for destitute children. One image featured two brothers, Thomas and Edward Hartley, ages 11 and 8, with Edward’s arms wrapped around Thomas in what looked like a loving embrace. Webb filed it as proof of institutional compassion. In 2019, 124 years later, digital restoration specialist Dr. Sarah Chen magnified the image to 12,800%. What surfaced made her physically ill: the embrace wasn’t love—it was terror—and the hidden details exposed one of Victorian England’s darkest secrets.

Thomas and Edward became orphans on March 3, 1895, when their mother, Katherine, died of consumption in a Manchester tenement. Their father had been crushed in a factory accident two years earlier at the Ashton Cotton Mill, where he worked 14-hour shifts for eight shillings a week. Katherine fought to keep the boys fed and housed—taking in laundry, sewing by candlelight, and going without food so they could eat. But consumption ignored sacrifice; by February, she could no longer work or breathe properly. Her sister Margaret Clark found her skeletal and fevered on March 2 and heard a dying plea: “Promise me—don’t let them go to the workhouse.”

Margaret promised, but she and her coal-miner husband already had six children in a two-room cottage. There was no space, no money, and no alternatives among relatives. Katherine died the next morning, with Thomas holding her hand while Edward sobbed into the blanket. Margaret tried three other families—each refused in hard times. On March 8, Margaret told Thomas through tears the only option was Blackwood Workhouse—and begged him to protect Edward.

Blackwood stood on Burnley’s outskirts, a three-story stone building that looked—and operated—like a prison. The workhouse system claimed to provide shelter and food, but was designed to be so harsh that the poor would avoid it at any cost. The theory: cruelty would motivate people to find work and stop burdening society. Thomas and Edward were children, not employable adults, and Blackwood under Master Harold Grimshaw was notorious for cruelty toward minors. Three separate people warned Margaret: the corner-shop keeper, a local priest, and a coal deliverer—all describing beatings, starvation, and screams from punishment rooms.

Margaret had no choice if she wanted to keep the brothers together; other facilities would split them. On March 10, 1895, Thomas and Edward were admitted to Blackwood Workhouse and assigned to boy ward C indefinitely. Neither boy ever left voluntarily. Six months later, notice came that an inspector from the Poor Law Board would visit on October 15. Grimshaw, furious, staged a “model” workhouse for three days—closing the oak shed, cleaning children, improving gruel, and emptying the punishment room.

Thomas was dragged out of isolation after 72 hours for stealing bread for Edward. Nurse Abigail Stone cleaned him and saw bruises in multiple stages of healing—finger marks and cane lines—then whispered: “Pull your sleeves down and button them. Do not roll them up tomorrow.” Thomas obeyed, hollow-eyed from six months of submission. Edward’s body fared better because Thomas took punishments for him, but the younger boy was psychologically shattered—flinching, silent, and screaming at night until Thomas held him.

Inspector Martin Whitmore arrived at 10 a.m. on October 15—decent, concerned, but rushed, with four hours to cover Blackwood before the next stop. Grimshaw showed him the cleanest wards, best-fed children, and “new equipment,” a carefully scripted performance. When Whitmore requested photographs for his report, Grimshaw had already hired Marcus Webb. Ten children were chosen for the session—including Thomas and Edward—washed, combed, and posed.

Grimshaw instructed Edward to put his arms around Thomas to show “sibling bonding” in a caring environment. Edward looked terrified; Thomas gave a tiny nod and whispered, “Just do what he says.” Marcus set his tripod and announced an eight-second exposure. Through his lens, it appeared tender—a younger boy seeking comfort from his older brother. Eight seconds preserved a moment that concealed more than anyone in that room could see.

Dr. Sarah Chen had twelve years’ experience restoring historical photographs when she began the Lancaster project, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. On August 3, 2019, she opened file LHP4472: Blackwood Workhouse, October 1895—children in the assembly hall. Most images showed rows of expressionless children. One photo of two boys in an embrace was labeled “example of sibling affection maintained in institutional care.” Something about it bothered Sarah—an instinct sharpened by years of reading faces.

She began restoration: dust removal, scratch repair, contrast and sharpness adjustments, aided by a well-preserved glass plate negative. At 400%, then 800%, then 1,600%, details sharpened. At 3,200%, she saw the older boy’s hands trembling—motion blur within an eight-second exposure—knuckles white and fingers clenched. At 6,400%, dark stains at the cuffs appeared—wrong color and texture for dirt. Sarah recognized dried blood.

At high magnification, the older boy’s face resolved into a mask of suppressed pain—eyes wide, jaw tight, fighting not to show suffering. At 12,800%, the maximum resolution, a half-inch of exposed forearm showed clear bruising—finger-shaped contusions consistent with a violent grip. On the neck, just above the collar, a circular mark about one inch in diameter appeared—consistent with a cane strike. The younger boy’s hands clutched fabric with desperate force; his neck and jaw were tense, not relaxed.

Records identified the boys: Thomas Hartley, 11; Edward Hartley, 8; admitted March 1895. Sarah checked Blackwood’s database and found two entries. Thomas Hartley, discharged December 1895—“ran away during night, not recovered.” Edward Hartley, died November 21, 1895—cause of death: pneumonia. Six weeks after the photograph, the younger boy was dead. Sarah called the Lancaster Archives Historical Research Department: “I think I’ve found evidence of child abuse—and a 124-year cover-up.”

Her call triggered an eight-month investigation by six researchers. Official records—admission logs, ledgers, death certificates, correspondence, inspector reports—painted a competent institution. Unofficial records—misfiled, overlooked, or hidden—told a different story. Senior archivist Dr. Robert Ashford pulled sealed parliamentary inquiry files from 1896, initiated by anonymous letters to social reformer George Lansbury. The testimonies, unsealed in 1996, had been largely ignored.

Nurse Abigail Stone testified: the Hartley photograph was a lie. Thomas had spent three days in isolation and had been beaten so severely she feared internal injuries. Grimshaw ordered her to clean him and conceal bruises. Edward was constantly terrified, barely ate, and woke screaming nightly; Thomas took punishments to protect him. Edward’s pneumonia was technically accurate—but driven by malnutrition, cold, and systemic abuse.

Coal delivery worker Samuel Brooks testified about children with bruises and ribs visible through skin. He saw a boy of about 10 or 11—hands bleeding while loading coal—who vanished months later. He later learned the boy’s name was Thomas Hartley, who ran away in December and was never found. Father Edward Davies testified that he conducted Edward’s funeral—an eight-year-old weighing about 40 pounds, at least 15 underweight. The undertaker showed extensive bruising inconsistent with pneumonia alone; Davies reported it to the board. Nothing happened.

Most damning was a letter in Grimshaw’s personal file dated October 20, 1895—five days after the photo. “The inspection was a complete success. Whitmore saw exactly what I wanted him to see. The photographs will be useful for fundraising. We can return to normal operations. The Hartley boys caused trouble during preparations but were appropriately disciplined. The younger one shows signs of illness; I expect he’ll recover or be removed soon.” Edward died one month later. Thomas disappeared six weeks after.

For 124 years, no one knew what became of Thomas after his December 1895 escape. In October 2019, three months into Sarah’s work, a woman named Margaret Preston contacted the archives. She believed her great-great-grandfather was Thomas Hartley, who had changed his surname to Preston when he enlisted in 1900, likely to avoid institutional return. She provided photos of Thomas as an elderly man, surrounded by grandchildren, smiling with eyes that carried decades of unspoken pain.

Sarah compared the 1895 image to later-life photos, using age-progression facial recognition. The system returned a 94% probability match—Thomas Hartley had survived. He fled in winter at age 11 and reached Liverpool, where a merchant captain took him in as a cabin boy. He spent his teens at sea, enlisted in the army at 16 by lying about his age, then settled in Southampton as a dock worker, married, and raised four children. He never spoke of Edward.

Margaret discovered a small leather journal from 1948, written when Thomas was 64 and ill. In a March 15 entry, he wrote: “I see Eddie’s face every night. He was 8, and he died because I couldn’t protect him. I promised Mother and Aunt Margaret I would protect him. I failed. Blackwood killed my little brother—starved him, beat him, worked him until he couldn’t stand, then let him die. I ran because I knew I was next. I am a coward. I left Eddie’s grave and carried that guilt for 53 years.”

The photograph, testimonies, journal, and digital restoration were presented to Parliament’s Historical Injustices Committee in March 2020. On November 21, 2020—exactly 125 years after Edward’s death—Parliament passed the Historical Institutional Abuse Recognition and Remedies Act, nicknamed the Hartley Act. It created a formal process to investigate historical institutional child abuse and issue posthumous acknowledgements. It built a national database of workhouse and residential-school records for researchers and descendants. It funded memorials and education to ensure victims are remembered.

The law was imperfect—it couldn’t bring Edward back or erase Thomas’s trauma or punish long-dead perpetrators. But it was recognition and accountability—an official statement: this happened, it was wrong, and we remember. On October 15, 2021—126 years after Webb’s photograph—a memorial was unveiled at the former Blackwood site. The building had been demolished in 1952; the land became a small public park in Burnley, with a single preserved stone wall.

The memorial is a bronze sculpture of two boys—one older, one younger—standing together. The older boy’s hand rests protectively on the younger’s shoulder; both face forward toward a future they never had. The inscription reads: “In memory of Edward Hartley (1887–1895) and Thomas Hartley (1884–1957), and all children who suffered in institutional care. Edward died here, age 8. Thomas survived but carried the wounds forever. May we never forget. May we never repeat.” Sarah Chen attended with Margaret Preston and three of Thomas’s great-great-grandchildren.

Over 200 people came—historians, activists, descendants of other victims, local residents, and schoolchildren who studied the case in the national curriculum. Panels showed the original image beside Sarah’s magnified restoration—secrets hidden in 1895, truth revealed now. “This photograph taught us that historical images aren’t neutral,” Sarah said at the dedication. “They were made by people with agendas—often something to hide. How many Victorian photos of clean children in orderly halls are lies?”

The memorial receives about 5,000 visitors annually. Many leave white roses for Edward and red roses for Thomas, along with notes: “You deserved better,” “We remember you,” “This should never have happened.” The glass plate negative is preserved at Lancaster Archives in climate-controlled storage. Sarah’s restored version is displayed at the National Justice Museum in Nottingham in “Hidden Histories: What Photographs Don’t Tell Us,” explaining how digital forensics unveils truths our ancestors missed—or ignored.

The exhibit is a favorite among school groups studying Victorian social history. In 2023, the BBC aired The Hartley Brothers: A Photograph’s Secret, viewed by 4.2 million and nominated for a BAFTA. Experts explained how pixels preserve evidence long after perpetrators die. Thomas Hartley died in 1957 at 73, surrounded by family who loved him. He built a good life from terrible beginnings—but carried the wound.

At the unveiling, Margaret Preston said it plainly: “My great-great-grandfather survived Blackwood, but part of him died there with Eddie.” He carried that trauma for 62 years, never spoke, never healed. The memorial is for Eddie, who died, and for Thomas, who survived but never escaped—and for all of us who carry inherited trauma from abuses done “in the name of charity.” Edward was 8—afraid of the dark, loved his brother, died cold, hungry, and in pain.

Thomas was 11—lost his last family, ran into winter darkness, and somehow survived. He built a life but never stopped seeing his brother’s face. The photograph shows an embrace; in truth, it shows a boy trying desperately to protect his brother from a world determined to break them both. 124 years later, we see the truth, say their names, and refuse to forget. Thomas and Edward Hartley mattered—and now their photograph ensures they always will.

News

What the German Major Said When He Asked the Americans for Help

May 5, 1945. Austria. The war in Europe has less than three days left. Hitler is dead; the German army…

“We Are Unclean,” — Japanese POW Women Refused the New Clothes Until American Soldiers Washed Hair

They had been told the Americans would defile them, strip them of honor, and treat them worse than animals. Yet…

American Doctor BROKE DOWN After Examining German POW Women — What He Found Saved 40 Lives

Texas, 1945. Captain James Morrison entered the medical barracks at Camp Swift expecting routine examinations. The spring air hung thick…

Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

She arrived in America with nothing but a small suitcase and a new name. Her husband called her Frances, but…

U.S Nurse Treated a Japanese POW Woman in 1944 and Never Saw Her Again. 40 Years Later, 4 Officers

The rain hammered against the tin roof of the naval hospital on Saipan like bullets. July 1944. Eleanor Hartwell wiped…

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory on Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

End of content

No more pages to load