Scene 1: The day the gate opened

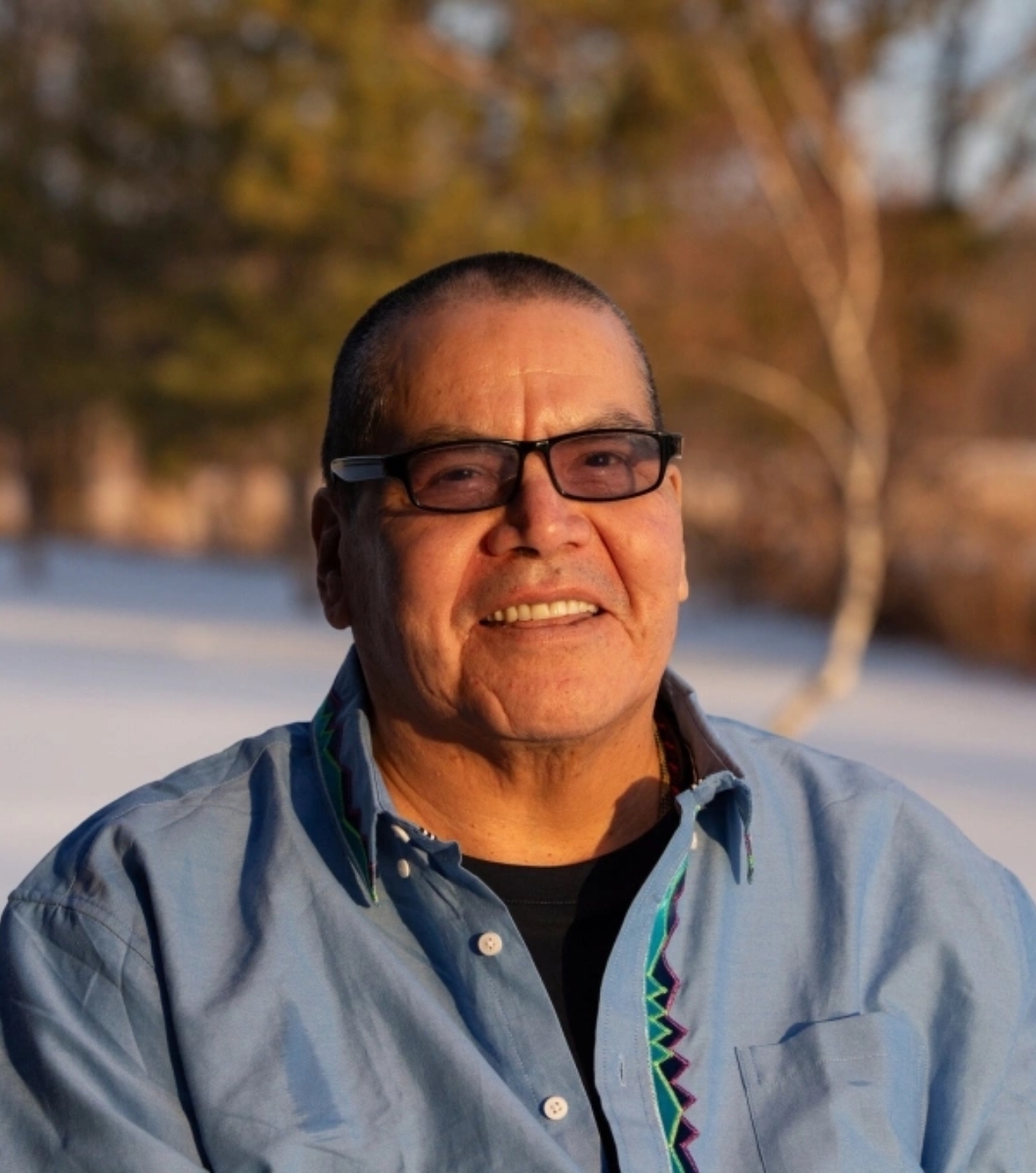

The morning air was cold enough to sting. A steel door slid on its track, and a 63-year-old man stepped forward with a paper sack of belongings and a stare that didn’t quite know where to land. His name is Brian Pippitt. He had entered prison in another century. On January 7, he walked out—after more than twenty-six years behind bars in Minnesota.

This was not a courtroom victory with cameras flashing and a judge’s gavel ringing out finality. It was a parole board’s decision, shadowed by something larger. According to the Minnesota Attorney General’s Conviction Review Unit, the case that sent him to prison had unravelled. In their words, “Mr. Pippitt should be declared innocent.”

– Scene 2: How a life sentence began

Go back to February 24, 1998. A small Minnesota town. An apartment beside a store. Inside, 84-year-old saleswoman Evelyn Malin was found beaten and strangled. It was a crime that shook neighbors, ignited fears, and set investigators on a path that would define lives for decades.

In 1999, police arrested several suspects. In 2001, a jury convicted one of them—Brian Pippitt—of murder during a robbery. He was sentenced to life in prison. The prosecution’s narrative was stark: Pippitt and four other men broke into the store to get beer and cigarettes; during the robbery, Malin was killed. The verdict was clear. The sentence was long.

– Scene 3: The man who said “I didn’t do it”

From the first hearing to the final appeal, Pippitt’s answer did not change. Not guilty. In interviews and filings, he insisted he had not been there. Over the years, he filed appeals that went nowhere. The rulings stood. The door stayed shut. And time, relentless and indifferent, kept moving. People he loved passed away. Photographs faded in his mind faster than they faded on paper. It is hard to convey the weight of years when every day ends in the same cell.

– Scene 4: A unit built for second looks

In 2021, the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office created the Conviction Review Unit—CRU, for short. Its mission was precise: re-examine claims of innocence with fresh eyes, gather new information, and assess whether a conviction still holds when tested against modern standards and the full record. According to the AG’s office, the unit has reviewed more than a thousand applications. Only a few have moved forward. Pippitt’s case became one of them.

– Scene 5: Two years of re-reading the past

The CRU’s review, as described by the Attorney General’s office, stretched across two years. Investigators read thousands of pages. They interviewed more than 25 witnesses and experts. They re-checked forensic threads. They scrutinized what, in 2001, had been the spine of the case: testimony from co-defendants who had struck plea deals, statements from a jailhouse informant who claimed Pippitt confessed, and a collage of details that looked persuasive under the pressure of a grieving community and a courtroom clock.

According to the CRU report, problems surfaced quickly. Two key witnesses recanted. The jailhouse informant’s account clashed with other evidence. And crucially, the fingerprints, hair, and DNA gathered from the scene did not match Pippitt. What had once sounded cohesive began to split at the seams.

– Scene 6: The anatomy of a fragile case

Cases that lean heavily on incentivized testimony are inherently delicate. Co-defendants who agree to cooperate can receive reduced sentences. Jailhouse informants can hope for better outcomes of their own. The law allows such evidence; courts instruct juries on how to weigh it. But when later reviews discover contradictions and retractions, the whole structure can wobble.

In Pippitt’s file, the CRU found enough wobble to raise a conclusion: the conviction could no longer stand when tested against the full record. Their language was unambiguous—he should be declared innocent. That conclusion does not come lightly from a state attorney general’s office. According to the AG, since the unit’s formation, only three cases had been recommended for exoneration at the time—this was the first in which the person was still incarcerated.

– Scene 7: Freedom, but not finality

A parole board can open a door. It cannot erase a conviction. On January 7, the Minnesota Parole Board granted Pippitt release. He stepped into the world still legally burdened by the old judgment. His next steps would head not to celebration, but to a courthouse in Aitkin County, where lawyers would seek to convert the CRU’s conclusion into a formal exoneration.

Outside, someone asked him what he most wanted. The answer was not grand. “Go for a walk. Look at the sky. The Milky Way.” He said he hoped to have a dog. He wanted to spend time with family—what remained of it. After the sentence, years had done what years do. Many of those he loved were gone.

– Scene 8: The crime, the victim, the respect she deserves

When a conviction falters, the first duty is to remember the person at the center of the loss. Her name was Evelyn Malin. She was 84. She was a familiar face in a small community, a neighbor whose routine made people feel that the world would keep its shape. What happened to her was brutal and wrong. Nothing about a review unit’s findings changes that. Justice, if it means anything, must hold grief and accuracy at the same time.

– Scene 9: A case built in a different era

The late 1990s were not ancient history. Yet criminal justice in that period was different. Forensic capabilities were not what they are now. Data systems were less connected. Best practices around lineup procedures, disclosure obligations, and informant use have sharpened since then. When a conviction is re-examined, part of the work is asking whether today’s standards would have caught what yesterday’s missed.

In Pippitt’s case, according to the CRU, critical gaps remained: no physical evidence tying him to the scene; reliance on statements that later collapsed; a narrative that, on its face, now looked less certain. Where once there had been a single path to guilt, now there were multiple reasons to pause.

– Scene 10: The weight of recantations

Recantations are complicated. Sometimes they are unreliable. Courts treat them with caution. People change stories for many reasons—fear, pressure, regret. But when recantations are accompanied by external contradictions—when other evidence fails to support the original account—the doubts multiply. The CRU said two cooperating witnesses stepped back from their initial testimony. That matters, especially when the original case depends so heavily on their words.

– Scene 11: The jailhouse informant problem

The jailhouse informant’s testimony was another pillar. He claimed that Pippitt confessed to killing Malin. The CRU found contradictions. They noted conflicts with timelines and other evidence. Informant testimony is a known risk factor in wrongful convictions nationwide. Some states now require pretrial reliability hearings or enhanced disclosures when such witnesses testify. The reason is simple: incentives can distort truth.

– Scene 12: No match at the scene

Perhaps the most straightforward detail is also the most haunting. The CRU report states that no fingerprints, hair, or DNA from the scene matched Pippitt. In some cases, that alone does not clear a suspect. People wear gloves. Scenes get contaminated. But taken with everything else—the recantations, contradictions, and alternative accounts—the absence becomes loud.

– Scene 13: Time, lost and unforgiving

Twenty-six years. Consider what changes in that span. Technology leaps ahead. Children become adults. Parents age. Some funerals are missed. Memories, even of innocence, can fray under the grind of repetition. Pippitt said from inside, “I can’t believe I’m sitting in prison. The legal system should be fair and protect the innocent, but it hasn’t done that.” Statements like that are common in prisons. What is uncommon is when an attorney general’s independent unit later echoes the core claim: this person should be declared innocent.

– Scene 14: What a CRU is—and isn’t

Conviction Review Units are not appellate courts. They do not substitute for juries. They are internal safeguards—a recognition that any system built by humans needs a structured way to revisit outcomes. Most applications do not pass initial screening. Many cases are affirmed. In the small number where exoneration is recommended, the point is not to accuse past actors of malice. It is to correct the record when new facts, better methods, or a fuller view demand it.

– Scene 15: The path to exoneration

Parole grants breathing room; exoneration rewrites the page. For a court to vacate a conviction or declare a person innocent, filings must be made, hearings held, and judges convinced. Sometimes prosecutors join defense counsel in stipulations. Sometimes they ask for retrials. In Pippitt’s case, the CRU’s conclusion is a compass—not a gavel. The next chapter will be written in Aitkin County Court.

– Scene 16: What happens after release

Reentry is a separate trial with no jury and no judge. You walk out with a bag and a new clock. Housing must be found. Identification restored. Health care resumed. Friends, if they remain, must learn the person you became. Employers weigh headlines against second chances. The gap between inside time and outside time is not measured in calendars alone; it is measured in the ways the world learned to live without you.

– Scene 17: The human scale of a headline

It is easy to talk about units and reports and “the system.” Harder to talk about mornings when the coffee tastes new because it wasn’t stirred in a plastic cup. About the first night you sleep without a count light cracking the door frame. About walking a block and realizing you do not know the cost of anything anymore. The practicalities are mundane and monumental at once.

– Scene 18: The victim’s family and the need for answers

For the family of Evelyn Malin, headlines about a release can reopen wounds. They deserve clarity. They deserve accurate accounting of what happened and who was responsible. A CRU’s conclusion that Pippitt should be declared innocent raises new questions: Who committed the crime? What becomes of the original co-defendants? Can the trail be retraced after so many years? The work of review is not the end of the story; it is a pivot to a different set of tasks.

– Scene 19: Systemic lessons

Pippitt’s case is singular, but its themes recur: reliance on incentivized testimony, absence of physical evidence, informant contradictions, and the long shadow of time. Jurisdictions across the country have implemented reforms—recorded interrogations, improved discovery practices, better eyewitness procedures, informant reliability checks, and access to post-conviction DNA testing. Reviews like Minnesota’s are part of that movement: an institutional way to say, “We will look again.”

– Scene 20: Numbers that frame the stakes

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, thousands of people have been cleared in the United States since 1989, losing an average of more than ten years each. Common factors include mistaken identifications, perjury or false accusations, and official misconduct. Each case is unique; patterns teach. In that landscape, a state attorney general’s office saying “should be declared innocent” stands out. It is not a casual sentence.

– Scene 21: A night sky

Asked what he wanted most, Brian did not say a campaign, a lawsuit, or a microphone. He said a walk. A sky. The Milky Way. That detail is almost too fragile to carry in a sentence. It holds twenty-six winters and summers, and more than 9,000 nights behind concrete. It holds a man’s belief in something simple—stars—that did not require anyone’s permission to exist.

– Scene 22: The law catches up

The next hearings will involve filings, affidavits, and, likely, testimony. Lawyers will argue about standards: newly discovered evidence, actual innocence, due process. Judges will ask whether the original verdict can survive the CRU’s findings. Prosecutors will decide whether to oppose, agree, or seek a new trial. The question is no longer “Is he free?” He is. The question is, “Will the law say what the review unit already has?”

– Scene 23: What it means to say “innocent”

Courts are careful with that word. Some exonerations are phrased as “vacated,” “dismissed,” or “not guilty” at retrial. “Innocent” is rarer—reserved for cases where evidence affirmatively shows a person did not commit the crime. The CRU’s language points there. Whether the court will join that specific word remains to be seen.

– Scene 24: The empty chair

Return to the small apartment in 1998 and the life of Evelyn Malin. There is an empty chair in a kitchen. A cup left in a sink. A neighbor who still remembers the knock on the door. Justice is not only about setting the innocent free; it is about honoring the dead with accuracy. That is why reviews matter. Not to relitigate for sport, but to make our record of the past true.

– Scene 25: The cost that cannot be paid back

If a court declares him innocent, compensation statutes may apply. Some states offer set amounts per year wrongfully imprisoned. Money helps buy a home, health care, time. It cannot return birthdays, or the people who died while he waited. It cannot recover the years when the night sky was a square of darkness through a narrow pane.

– Scene 26: The road ahead

Pippitt’s lawyers will keep filing. The Attorney General’s office will keep reviewing. A county court will set dates. Reporters will call. Somewhere, a man will clip a leash onto a dog that does not yet know how important it is to sit in the sun while he drinks his coffee and learns the silence of a world without count bells.

– Scene 27: A final note on certainty

Stories like this invite strong reactions. Some will ask, “How could this happen?” Others will say, “Be cautious—the process must run its course.” Both are right in their way. The CRU’s conclusion is powerful. The court’s order will be decisive. In between is a man, a family grieving a lost loved one, and a state trying to write a more accurate sentence than the one it wrote in 2001.

– Scene 28: Closing

Twenty-six years. One life sentence. And a review that says he should be declared innocent. The steel door closed behind him on January 7. Ahead was a winter sky. The constellation he wanted was out there somewhere—unchanged by all that had changed. He walked forward, and for the first time in a long time, the path did not end at a gate.

News

Emma Rowena Gatewood was sixty‑seven years old, weighed about 150 pounds, and wore a size 8 shoe the day she walked out of the ordinary world and into the wilderness.

On paper, she looked like anyone’s grandmother. In reality, she was about to change hiking history forever. It was 1955….

21 Years Old, Stuck in a Lonely Weather Station – and She Accidentally Saved Tens of Thousands of Allied Soldiers

Three days before D‑Day, a 21‑year‑old Irish woman walked down a damp, wind‑bitten corridor and did something she’d already done…

JFK’s Assassination Was Way Worse Than You Thought

So, he’s finally done it. What do these new documents tell us about that fateful day in Dallas? In 2025,…

US Navy USS Saufley DD465 1952 Living Conditions

The USS Southerly was a general‑purpose 2,100‑ton destroyer of the Fletcher class. She was originally equipped to provide anti‑aircraft, surface,…

Man Finds Birth Mother and Uncovers His Family’s Unbelievable Past

Air Force Colonel Bruce Hollywood always knew he’d been adopted. His Asian features clearly didn’t come from his parents, who…

Before the wedding began the bride overheard the groom’s confession and her revenge stunned everyone

The bride heard the groom’s confession minutes before the wedding. Her revenge surprised everyone. Valentina Miller felt her legs trembling…

End of content

No more pages to load