– Prologue: The Ambush at Marjah

The heat curled off the canal like a living thing. Dust hung in the air as the convoy crawled along a narrow track, engines grinding at the edge of failure. Locals had vanished from doorways—eyes that once followed vehicles now shuttered behind splintered wood. Chantelle Taylor felt the threat before she could name it: the silence that falls just before noise becomes violence. When the world erupted, she did not think—she moved.

Explosions slammed the column from the flank and rear, shockwaves hammering metal into shrapnel and breath into panic. Her vehicle heeled under the blast, grit filling her mouth, the radio flaring with half-words and a sudden spike in heart rates. A muzzle flash bloomed from the left bank, clean and unmistakable, like a match struck in a dark room. She shouldered the SA80, found her sight picture, and did the thing training makes almost holy: exhale, control, decide. The trigger broke.

– Part I: Roots of a Soldier

Plymouth’s housing estate taught economy—of space, of noise, of hope measured in weekends. As the youngest of five, Chantelle learned to listen more than speak, to move through rooms without disturbing their settled weather. No one in the family wore uniforms or polished medals; the closest thing to regimental discipline was who did the washing up. Her first memory of the body under stress came in a playground: a fall, a cut, the staccato cry of a child who didn’t want help but needed it anyway. Her hands shook as she pressed a tissue to the bleed. She learned two truths in that moment—fear is loud; action is louder.

At twenty-two, with no mythology to make it easier, she walked into a recruiting office and said yes to something that would say no to her many times. April 1998 felt like a dare she finally accepted. Basic training did not disappoint in its cruelty. Ravines of exhaustion opened under her feet day after day, while the shouted cadence pounded doubts into a fine dust. Rules felt like a set of chains worn by choice. The thought of leaving crept up on her during pre-dawn runs, then receded when she found she could carry more than she thought.

The shift came quietly—like weather changing without ceremony. Confidence grew in the way she slept, fully spent, or how she checked lockers with a pride that surprised her. Somewhere between blisters and blunted pride, the Army started feeling less like punishment and more like a language she could finally speak. When it came time to choose a specialty, she walked toward the word that called her bluff: combat medical technician. The reason she gave later was simple, almost defiant—it was the only role that had “combat” in the title. If she was going to be there, it wouldn’t be halfway.

– Part II: Forged From the Inside Out

The first weeks in trade training peeled away illusions of heroics and replaced them with rituals. She learned to inventory trauma kits by touch, to read a pulse like a clock, to make decisions that outran panic. Physical pain sharpened her focus; discipline became a form of kindness to her future self. The corporal who ran drills had a voice like gravel and a heart like a metronome—steady, never sentimental, always on time. On a rain-soaked night exercise, when fatigue smudged voices and maps alike, he paused over her casualty assessment and said, “You can’t save someone you refuse to look at.” She looked.

When the day ends and nothing lives but the hum of fluorescent lights, you learn tiny liturgies: folding bandages with the same neat corners every time, labeling vials in block letters you could read in smoke, checking the weight of your pack twice because it will be different when it’s wet. She got good at the small things, because the small things become the big things when bullets and minutes start arguing. Somewhere in that grind, she decided the job wasn’t merely about not failing—it was about being the person others could hand fear to without apology.

– Part III: Lessons from Kosovo

Kosovo did not smell like war movies. It smelled like wet dirt and old grief. The Canadian detachment she joined moved with quiet precision, paperwork stitched to empathy, spade next to camera, evidence bag next to prayer. A mass grave is not a headline when you’re in it—it is a grid to be respected, a method that keeps chaos from eating dignity. Chantelle learned how to mark bones without erasing names, how to hold silence while others held outrage. Genocide is the word you write later; in the moment, it’s counting and cataloging and promising yourself you will remember.

She saw what policy does when it metastasizes into orders: houses emptied, the language of neighbors turned into ammunition, family histories stalled at the edge of a ditch. Most people would break right there, bending under the weight of the idea that humans can do this to each other. She chose a different path—absorb the lesson, don’t let it calcify into cynicism. Every evening she wrote in a notebook with lines so fine they felt like a map. The entries weren’t dramatic; they were records of what she needed to hold: times, faces, the way hands tremble when they touch what was once a person. The ritual kept her sane.

– Part IV: Sierra Leone—Twenty-Four and the Children’s War

The jungle made its own laws. Sierra Leone in 2000 meant humidity that could drown a thought and insects that negotiated land use with your blood. The forward sites were patchwork survival—tarps, cots, a radio that favored static over urgency. Her first serious combat injuries arrived with the sound of panic riding shotgun. Airway, breathing, circulation—the mantra rose like a staircase she took two steps at a time. She learned that stopping bleeding is a race, not a prayer, and that fluids are hope when hope feels theoretical.

Then came the children. Some had talismans around their necks; some had eyes too old for faces too young. Child soldiers are both perpetrator and victim—untrained hands forced into trained violence. The first time she cleaned blood from a boy’s hands with saline, he flinched at kindness like it might bite. Chantelle did not make speeches about innocence; she threaded needles and stitched wounds, and later she stared at the tent roof, counting loops to keep from crying. The moral geometry of war shifted. You could not unsee it. You could only decide not to look away.

– Part V: Private Loss—A New Armor

In 2002, grief found her not through a casualty report but through a family phone call. David, her brother, was gone. The kitchen where she grew up felt too small for all the words that could not be said. Grief is odd—it takes up space like a person you have to step around. Chantelle did not become a statue of stoicism; she became more alive in the parts of life that demanded action. Working harder was not a cliché—it was specific: hours on protocols until muscle memory could stand in for thought, checklists rehearsed until they became hypnosis, the MEDEVAC nine-liner drilled until it could be shouted through chaos.

When the invasion of Iraq came, purpose offered itself as medicine that did not promise cure but did blunt pain. She welcomed the mission because structure holds you when everything else slips. The desert carried its own language—rotor wash, dust storms, the scent of fuel that braided with sunrise. She learned to simplify under pressure: one thing, then the next, then the next. Complexity is arrogant in the face of blood; she became simple on purpose.

– Part VI: Iraq—Where Purpose is a Drug

Her team was a collage of accents and temperaments, a small nation that moved together because moving apart meant failure. The rules were clear: stabilize and move; do not become a shrine to indecision. She found mentors who trusted her with difficult, ugly tasks—the kind that keep people alive without making anyone look heroic. One taught her a trick with securing IV lines when the patient won’t stop shaking; another showed her how to change tone without changing the truth when telling someone what might happen next. The thing about war is that the lessons arrive whether you invite them or not. She took them in.

Fear did not leave; it learned to sit where it could be watched. She did not romanticize adrenaline—she used it like a tool. Recovery tents became classrooms at odd hours, with stories swapped like trauma currency and laughter engineered to puncture dread. Somewhere between sorties and sleep, she discovered she could meet the world at its worst and still find the means to act decently.

– Part VII: Helmand 2006—Hospital Under Canvas

Camp Bastion was a city of improvisation. The tented hospital was a daily miracle in beige: lines of stretchers, nurses whose hands were metronomes, surgeons who made time expand when it needed to. Chantelle stood at the hinge where arrival becomes care—triage that saw beyond blood to pattern, prioritization that saved the many because it refused to favor the loud. The British push into Helmand wrote its own dictionary: ambush, IED, casualty chain stressed to breaking.

Personal fear stalked her like a shadow she refused to acknowledge in public. Her fiancé served with the Parachute Regiment somewhere out there. Every dust-covered boot that crossed the threshold could have been a messenger of her own undoing. The nurses worked like saints without pews—long shifts, limited kit, pride stitched into their sleeves. Chantelle watched, learned, and filed it away under a heading she would need later: appreciation for the sharp end, where your best plan always meets someone else’s worst day.

– Part VIII: Return 2008—Thinking Like a Commander

Lashkar Gah headquarters wrapped her in responsibility that no patch could summarize. Managing medical assets during mass-casualty events meant arithmetic that included risk to pilots, not just need of patients. Helicopter crews are people, not platforms; she became allergic to decisions that treated them otherwise. “Best outcome for everyone” is the beautiful phrase that messes up easy choices. She accepted the mess.

The change was subtle but profound—she began to think in maps, not lists. The medic and the commander started sharing a brain. It wasn’t about rank; it was about range, the ability to see far enough to make near decisions that did not betray the future. Tactical awareness is compassion in war’s dialect. She learned to speak it.

– Part IX: Marjah—1.5 Seconds That Define a Life

They set out along the canal with a script in mind: go long, stay tight, read the air. The script broke in the way scripts do when the other side writes their own. Locals looked wrong. The temperature climbed past comfort into caution. The convoy advanced. The first blast made a joke of the horizon; the second turned the joke cruel.

Her vehicle shuddered, metal screamed, and her mouth tasted earth. Gunfire from the left and rear stitched the air, a pattern the Taliban had perfected like a bad hymn. She saw him—a man moving to pin their vehicle in place, his intent as visible as the weapon he raised. Training shouted through her bones. SA80 up. Sight clears. Breath tamed. Decision made. She squeezed. It was not mythic; it was necessary.

The radio flared with a new urgency—someone hit in the rear. Her commanding officer’s voice cut through the din, and together they moved—out, forward, toward the casualty, then back when a garbled update said first aid had already landed. The patrol peeled away from the kill zone, and a helicopter clawed at the sky, promising evacuation and delivering it under fire. Later, when asked why, she said the only phrase that fit: “We had to neutralize the threat.” The sentence is clean; the memory is not.

– Part X: Seven Weeks in Nad-e Ali—The Golden Hour in Hell

B Company set up in a patrol base that might as well have been a target pinned to a board. Kajaki echoed through the operation like a place you’d rather not remember but cannot forget. Over seven weeks, one hundred British troops and a small Afghan contingent absorbed sixty-six casualties. Numbers are dry until you’re the one counting bodies and breaths.

Medical work is a race disguised as ritual. Tourniquets bite. Tranexamic acid buys time. Airways are negotiated like peace treaties. The nine-liner MEDEVAC report becomes poetry shouted over gunfire—location, call sign, number and type of patients, special equipment, site security, method of marking, patient nationality and status, NBC contamination. Dustoff crews risk their own lives so you can push someone toward survival. Chantelle ran that race lulled by nothing but urgency.

Heat made even thinking a labor. Food was an afterthought, monotony served three times a day. Sleep was a rumor. Attacks were a habit. And yet the team made a culture out of competence—respect traded like currency, jokes timed like medicine, anger edged into focus. The Afghan National Army soldiers watched the British medics and began to mimic—not bravado, but care. Trust was not declared; it was earned in the bloody minutes no one dramatizes for audiences who love clean endings.

– Part XI: Homeward—Honors, Options, and a Left Turn

Back in Britain, the arc of a career bent upward—staff sergeant, the murmur of a commission. The suggestion felt like a compliment and a trap. Chantelle said no because she understood the geometry of her own life: new challenges called louder than new rank. Her comrades gave her farewells that mattered more than plaques.

One gift stood above the rest: a trophy of Bellerophon mounted on Pegasus—the emblem of airborne forces. Those who jump from planes don’t share their icons lightly. The statue said what men often refuse to say plainly: you are one of us. It sat on a shelf where she could see it from the doorway, a reminder that belonging sometimes comes disguised as a myth on a horse.

– Part XII: The Front Line by Other Means

It’s hard to leave war without circling back. In 2009, she returned to Afghanistan, this time under the U.S. Department of State, training Afghan soldiers in combat medicine. “Train the trainer” is the boring phrase for a radical act—giving people the tools to save their own, not waiting for rescue. Her classrooms were whatever stayed standing that week. Her curriculum was survival.

Then she changed theaters without changing the stakes—diplomatic security, primary protection for the Australian ambassador to Iraq. Route planning replaced patrol routes; threat assessments replaced enemy sitreps. The work asked for the same things—attention, restraint, readiness. The job was to be invisible until the moment you charged at danger. She could do invisible. She could do charge.

– Part XIII: What Remains

Being “the first British woman to kill an enemy in close combat” reads like a headline that threatens to shrink a life into one frame. Chantelle did not seek the label; she lived a set of choices that made it inevitable. The battles matter, but so do the hours when nothing happens and preparation is everything. The medals matter, but so does the hand squeeze in a helicopter when a patient decides to stay.

Her story is not about barrier-breaking as theater; it is about utility under pressure. She did work where failure doesn’t say sorry. She made decisions where perfection is required but rarely possible. She stood with her team when hell tried to teach them its grammar. She did not claim fearlessness; she practiced courage—the art of acting correctly while afraid.

– Coda: The Trigger and the Thing No One Saw

Return to the canal, to the heat that distorts sightlines, to the dust that makes breath an argument. Slow the frame. Watch the sight settle, the micro-tremor vanish, the line between hesitation and choice thin to a thread. Feel the stock against the shoulder, the mind briefly empty, the body remembering what it was taught.

Stop before the sound. Hold the silence where futures are decided. Let consequence hover, unnamed, heavy. And ask yourself: when your own 1.5 seconds arrive—what will your hands know that your mind cannot say? Who will you be when the world erupts and the only honest answer is action?

News

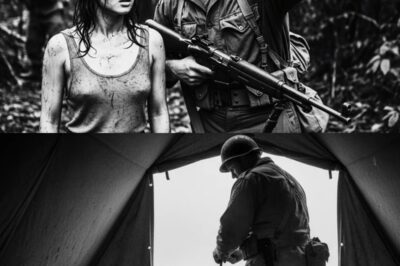

“You’ll Sleep in My Tent!” — The Moment An American Soldier Rescues Japanese Girl POW from Bandits.

– January 15, 1945. The foothills of the Caraballo Mountains, Luzon, Philippines. The jungle floor is a tapestry of decay—rotting…

Luftwaffe Aces Couldn’t Believe How Many B-17s Americans Could Build

– A German fighter pilot watches the sky turn black with American bombers—again. He’s just shot down his third B-17…

The General Asked, “Any Snipers Here?” — After 13 Misses, a Simple Woman Hit Target at 4,000m

– Arizona Defense Testing Range. Midday sun beats down on concrete and steel. Thirteen professional snipers—all men—stand in a line….

“You Paid For Me… Now Do It” — The Rancher Did It. And Then… He Had A Wife

– The wind cut across the open land like a blade—cold and sharp—finding its way into your bones. A tired…

When American Soldiers Found 29 Frozen German Nurses in 1945 A Heartbreaking WWII True Story

– The date is February 1, 1945. The location: a frozen forest near the Elbe River in Germany. The temperature…

Bumpy Johnson’s Daughter Was KIDNAPPED — What He Did in the Next 4 Hours Became LEGEND

– June 15, 1961, 8:04 a.m. Mrs. Johnson walked into her daughter’s bedroom. Ruthie wasn’t there. The bed was made,…

End of content

No more pages to load