April 13th, 1945. The outskirts of Weimar, Germany. A beautiful, sunny spring day. A group of American soldiers from the 80th Infantry Division kicked open the door of a luxury villa. The house was pristine—expensive rugs, crystal chandeliers, fine art on the walls. The air smelled of expensive French perfume.

It looked like the home of a movie star, but it wasn’t. It was the home of Ilse Koch, the wife of the commandant of Buchenwald, the woman the prisoners whispered about in their nightmares. They called her the Witch of Buchenwald. The soldiers began to search the house. They were looking for SS officers. They were looking for weapons. But in the study, they found something else.

An American sergeant walked over to a table. On it was a lamp. It was a beautiful lamp. The base was made of wood. The shade was made of a strange pale leather, translucent and delicate. The sergeant touched it.

It felt odd. It didn’t feel like cow leather or goat leather. It had a texture that made his skin crawl. Then he looked closer. He saw faint lines. He saw a pattern that looked like a tattoo.

He froze. He called the medic. “Doc, come take a look at this.” The medic examined the lamp. He examined the book covers on the shelf. He examined the gloves lying on the desk.

He looked at the sergeant, his face white. “Sarge,” he whispered, “that’s not leather. That is human skin.” The soldiers recoiled. They were standing in a house of horrors, a house decorated with the bodies of murdered men.

This is the true story of Ilse Koch, often described as one of the most evil women of the Third Reich. It is the story of her twisted obsession with tattoos, her collection of human souvenirs, and the moment American justice finally caught up with the “witch.” To understand the horror found in that villa, we have to go back a few years to the height of Nazi power.

The Commander’s Wife: Life of Luxury

Ilse Koch was not a soldier. She held no military rank. She was a secretary, but she married power. Her husband was Karl Koch, the first commandant of Buchenwald concentration camp.

They lived in a large, beautiful villa right next to the camp. It was a surreal existence. On one side of the fence: starvation, torture, and death. On the other: garden parties, expensive wine, and music.

Ilse loved the power. She treated the camp like her personal kingdom. Prisoners who survived tell a chilling story. They remember her riding her horse.

She would ride through the camp inspection grounds. She was beautiful—red hair, tight riding clothes. But in her hand she carried a whip, a riding crop tipped with razor blades.

If a prisoner looked at her, she would slash his face. If a prisoner didn’t look at her, she would whip him for disrespect. She played a sadistic game.

She would wear provocative clothing to taunt the starving men. If anyone dared to glance, she would note down their prisoner number. That prisoner would disappear. But her cruelty wasn’t just physical.

It was “artistic.” She had a hobby, a collection. It started as a rumor among the prisoners. “Don’t show your skin. Hide your arms. If she sees your art, she will want it.”

The Tattoo Inspection: Selecting Victims

Ilse Koch was fascinated by tattoos. In the 1940s, tattoos were rare. They were usually found on sailors or criminals. Many of the prisoners at Buchenwald were criminals or political prisoners who had elaborate inkwork—ships, eagles, names of lovers.

Ilse Koch would attend the medical inspections. The prisoners were stripped naked, shivering in the cold wind. They stood in lines in the freezing air.

Ilse would walk down the line like a shopper in a grocery store. She wasn’t looking for lice or disease. She was looking for art. When she found a tattoo she liked—maybe a beautiful sailing ship on a man’s chest—she would smile.

She would ask the doctor, “Is this specimen healthy?” If the doctor said yes, the prisoner was doomed. He wasn’t sent to the work gangs. He was sent to the pathology lab.

The Pathology Lab (The Evidence)

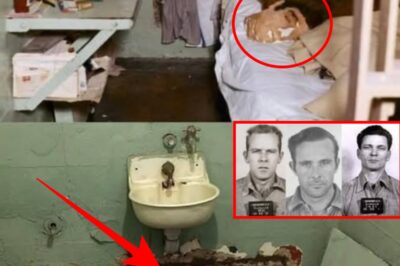

The pathology lab at Buchenwald was the center of the nightmare. This is where the American soldiers found the evidence that shocked the world. When the US Army liberated the camp, they found the lab intact.

Inside, they found jars—glass jars filled with alcohol. Floating inside were pieces of skin. There were hundreds of them, perfectly preserved squares of flesh. Some had pictures of birds. Some had dates. They were “specimens.”

But the skin wasn’t just for jars. According to witnesses at the Nuremberg trials, Ilse Koch had a special request for the camp doctors. She wanted functional art.

She ordered lampshades, book covers, gloves, wall hangings—all made from the tanned skin of the prisoners she selected. Imagine the psychology of a woman who sits in her living room reading a book bound in the skin of a man she had murdered under the light of a lamp made from another man’s chest.

It was a level of depravity that even battle‑hardened American soldiers couldn’t comprehend. When General Patton saw the lab, he was furious. He described it as the work of animals. But there was one more thing in the lab—something even worse than the skin.

The shrunken heads. Two human heads, shrunken to the size of a fist, preserved like tribal trophies. One was the head of a Polish prisoner who had been caught escaping. Ilse Koch kept them as paperweights.

The Witch is Captured

By 1945, the game was up. The Americans were coming. Her husband, Karl Koch, was already dead—executed by the SS themselves for corruption and theft. He had stolen from the Nazi state, which was the only crime the Nazis cared about.

Ilse fled. She tried to blend in. She went to live with her family in the town of Ludwigsburg. She thought she could hide.

She thought she was just an officer’s wife. She thought nobody knew about the lampshades. But the prisoners knew. When the Americans liberated Buchenwald, the survivors poured out their stories.

They told the intelligence officers about the red‑haired witch. They described the tattoos. They described the whip. The US Army launched a manhunt.

Intelligence agents tracked her down. On August 19th, 1945, they found her. She was living comfortably. She acted surprised when the MPs arrested her.

“I am just a woman,” she said. “I never hurt anyone. I was just the wife of the commandant. I had no rank.” She played the victim. She played the innocent mother.

But the Americans had the evidence. They had the lamp. They had the shrunken heads. And they had thousands of witnesses who were ready to point the finger.

The Trial: The Showcase in Court

1947. Dachau. The Americans set up a military tribunal to try the war criminals of Buchenwald. Sitting in the dock were 30 men—SS officers, doctors, executioners—and one woman: Ilse Koch.

She was the star of the show. The press called her the “Bitch of Buchenwald.” She sat there, cold and arrogant. She stared at the judges.

The prosecutor brought out the evidence. He placed the objects on the table. The courtroom went silent. He showed the tanned skin. He showed the shrunken heads.

He brought in witnesses—former prisoners—who testified. “She pointed at me. She wanted my tattoo.” “I saw her hitting children.” “I saw the lamp in her living room.” Ilse denied everything.

She claimed it was goat skin. She said the prisoners were lying. She insisted it was all American propaganda. But the judges didn’t buy it.

She was found guilty. She was sentenced to life imprisonment. It seemed like justice. The witch would rot in a cell forever.

General Clay’s Controversial Decision

But then something shocking happened—something that made the American public scream with rage. General Lucius D. Clay was the American military governor of Germany. He was the man in charge of reviewing the sentences.

In 1948, he looked at Ilse Koch’s file. He was a lawyer at heart. He reviewed the technical evidence. He decided that the evidence of the lampshades was circumstantial.

The skin had disappeared—some say stolen by souvenir hunters. The witnesses were considered unreliable according to strict legal standards. So, General Clay did the unthinkable.

He reduced her sentence from life to four years. Four years for the woman accused of making human art. Since she had already served two years, she would be free in 1949.

When this news hit the United States, the reaction was nuclear. Newspapers ran headlines: “The Witch Goes Free.” Senators demanded an investigation. Holocaust survivors protested in the streets.

They couldn’t believe that the US Army was letting a monster walk away. General Clay stood by his decision. “There was no convincing evidence that she selected inmates for extermination in order to secure tattooed skins,” he argued.

He was technically right by the law books, but he was morally wrong in the eyes of the world. Ilse Koch walked out of the American prison in October 1949. She thought she was free. She smiled at the cameras.

She thought she had won. But she forgot one thing. The Germans hated her too.

German Justice: Rearrested

The moment she stepped out of the American prison gate, West German police officers were waiting for her. The Americans had let her go, but the new West German government arrested her immediately. They charged her not with war crimes, which the Americans handled, but with murder and attempted murder of German citizens inside the camp.

This time, there was no escape. The German trial was even more brutal. More witnesses came forward. More evidence was found.

The German prosecutor was relentless. He called her a perverted beast. In 1951, the German court sentenced her to life imprisonment with hard labor.

No parole. No early release. The witch was locked away for good.

The Ghost in the Cell

Ilse spent the next 16 years in a German women’s prison. She became delusional. She claimed she was the victim of a conspiracy. She insisted she was a loving mother who just wanted to ride horses.

She wrote letters to her son, Uwe. Uwe had been born in prison—a scandal in itself. He tried to visit her. He tried to understand why his mother was the most hated woman on earth.

But even he couldn’t find a trace of humanity in her. On September 1st, 1967, Ilse ate her final meal. She wrote a note: “I cannot do this anymore.”

She took her bedsheets, tied them to the window bars, and hanged herself. She died at 60, alone in a cold cell, just like the thousands of victims she had helped torture and kill.

The story of Ilse Koch is one of the darkest chapters of humanity. It forces us to ask: “How does a normal person—a secretary, a wife—become a monster?” She wasn’t forced to do it.

She didn’t have orders from Hitler to make lampshades. She did it because she enjoyed it. She did it because absolute power corrupts absolutely.

The Legacy of Evil

When the American soldiers kicked down her door in 1945, they didn’t just find a lamp. They found the darkness that lives inside the human soul. The lamp itself disappeared.

Some say it was destroyed. Some say it is hidden in a private collection. But the memory of it remains—a symbol of ultimate cruelty. General Patton was right to be sick. Eisenhower was right to film it.

Because stories like this are so horrible that we want to believe they are fake. We want to believe that humans aren’t capable of this. But the Witch of Buchenwald proved that they are.

She thought she was untouchable. She thought she was a queen. But in the end, she was just a prisoner, and her legacy is nothing but ash and shame.

The lamp made of human skin is one of the most debated artifacts of World War II. Some say it never existed. Others swore they saw it. Based on the testimony, do you believe the stories about Ilse Koch were true?

Let me know your thoughts in the comments. And if you want to see the story of how American soldiers took revenge on the SS guards at Dachau, click the video on the screen. Thanks for watching.

News

The Night Alcatraz Blinked

For decades, Alcatraz stood as a sentence, not a place. A slab of rock in the middle of San Francisco…

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

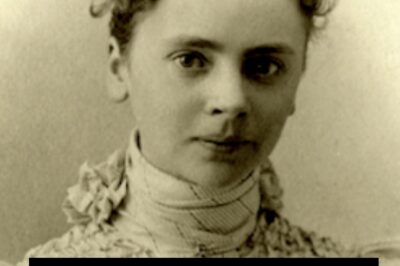

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

“You’re Not Animals” – German Women POWs Shocked When Texas Cowboys Removed Their Chains

June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid….

End of content

No more pages to load