March 23, 1945, 10:47 a.m. Winston Churchill sat aboard his command aircraft, minutes from landing to witness British glory. Field Marshal Montgomery’s Operation Plunder—the meticulously planned Rhine crossing—was set to showcase British professionalism to the world. Then the radio crackled with four words that froze him: “Patton crossed last night.” Not with a thousand guns and airborne drops—just boats and what Patton called “a band of angry Pennsylvanians.”

Montgomery’s immediate cable to Churchill held two sentences: “American insubordination has made a mockery of Allied planning. Patton must be relieved of command immediately.” What Churchill said next—to Montgomery, to his inner circle, and in a whisper to his physician—would reveal alliance warfare’s brutal truth: pride has a price, and wars are won by choosing results over protocol. To grasp Churchill’s dilemma, you must understand what Montgomery had been promised.

On January 12, 1945, Churchill personally assured Montgomery that Plunder would be the centerpiece of Allied victory—British professionalism, not American improvisation. For two months, Monty planned: 1.2 million men, 25,000 vehicles, 3,500 guns, airborne drops, smoke screens—the largest river crossing since Normandy. Churchill invited correspondents, arranged photographers, and drafted the communiqué that would hail British excellence the moment the east bank was secured. Everything was ready—except George Patton.

March 22, 10:37 p.m. Patton called Eisenhower from Luxembourg. “Ike, quick update—we crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim. Assault boats. Minimal casualties. Thought you’d want to know.” Eisenhower’s reply, captured in telephone logs, betrayed the political catastrophe. “George, please tell me you coordinated with Montgomery.” Patton’s answer was pure Patton: “Monty’s got his crossing tomorrow. Didn’t want to bother him with details.”

Eisenhower hung up and called his chief of staff. “Get me Churchill. George just created the biggest diplomatic crisis of the war.” By 6:18 a.m., Montgomery had confirmation: Americans had crossed twelve hours before Plunder. He didn’t shout—he went cold. “Patton has deliberately sabotaged Allied strategy to satisfy his ego. This is strategic-level insubordination. I want him relieved, court-martialed, and sent home—today.”

His chief of staff tried moderation. “Sir, the crossing was successful. Third Army is expanding the bridgehead.” Montgomery cut him off. “Success is irrelevant. Discipline is paramount. Allow this, and we have chaos, not coalition.” He drafted an immediate message to Churchill: “American general conducted unauthorized operation violating agreed framework. Request you demand Eisenhower relieve Patton. British forces cannot operate alongside commanders who ignore command.”

Churchill received Monty’s cable at 9:15 a.m., minutes before landing. “Ismay, what are the facts?” “Sir, Patton crossed at Oppenheim last night. Under thirty casualties. Bridgehead secure. No elaborate preparation. No permission.” Churchill stared out at Germany below. Monty was his chosen general, his protégé, the careful professional who embodied proper conduct. But Patton had crossed Hitler’s last natural barrier before Monty could even begin.

The political math was brutal. Support Montgomery, and Churchill would demand the firing of an American general for succeeding too quickly. Support Patton, and he would undercut British prestige in front of the world. At 10:52, Churchill’s plane touched down. Montgomery stood waiting—ramrod straight. “Prime Minister, thank you for coming to witness Operation Plunder.” Churchill kept his tone neutral. “Field Marshal, I received your message. Walk with me.”

Montgomery began at once. “I must insist Patton be relieved. His insubordination cannot stand.” Churchill raised a hand. “Bernard, answer one question honestly. If Patton had asked permission to cross last night, what would you have said?” Monty didn’t hesitate. “Denied. His crossing diverts attention from the main effort.” “Your main effort,” Churchill said. “The Allied main effort, as agreed by planners.”

Churchill paused. “By planners who gave you two months and gave Patton nothing. Bernard, is this about strategy—or pride?” Monty flushed. “It’s about maintaining command discipline.” Churchill’s reply was quiet, devastating. “It’s about Patton making you look slow.” The words hung in the cold air. “I’ve defended your methods for three years—preparation, overwhelming force, minimal casualties. The British way.”

“But watching Patton cross with boats while you required two months for the same objective raises uncomfortable questions,” Churchill continued. Monty stiffened. “Are you suggesting American methods are superior?” “I’m suggesting American speed achieves results we can no longer match.” Churchill turned to him. “The war is ending. Germany is collapsing. Every day we spend on perfect preparation is a day the Soviets move west. Patton understands this.”

“So you choose him over me?” Monty demanded. Churchill shook his head. “I choose to end the war before the Soviets claim half of Europe. That requires speed we no longer possess.” He had wrestled with this truth for months. After Bastogne’s relief in 72 hours, he wrote: “Patton does in days what takes us weeks.” In January, watching Patton race while Monty crawled, he confided: “The Americans move faster than we can think.”

Now, on a German airfield, Churchill accepted the conclusion he had resisted. British doctrine—the doctrine he had defended—was being surpassed by American operational tempo. Monty tried once more. “If Patton isn’t disciplined, command authority means nothing.” Churchill answered with the most honest assessment of Allied politics ever recorded. “You’re right. Patton violated protocol, bypassed coordination, and made us look foolish.”

“But if I demand Ike fire him, I must explain we are removing America’s most successful general because he succeeded too quickly without British permission. Do you understand how that sounds?” Churchill pressed on. “The Americans provide seventy percent of Allied strength, bear most casualties, and fund this entire enterprise. Their general crossed the Rhine in one night while we needed two months and a million men.”

“If I demand his firing, I admit British pride matters more than Allied victory.” Artillery answered him—Plunder had begun. Monty’s crossing was underway, brilliantly planned, but suddenly secondary. Churchill placed a hand on Monty’s shoulder. “You are one of Britain’s finest. History will remember your victories. But it will also record that an American crossed first—not because he was better, but because he risked speed while we calculated caution.”

“So I’ve lost,” Monty whispered. Churchill shook his head. “We’ve all lost something. You’ve lost precedence. I’ve lost the illusion that British methods still define modern war. But we are winning. That must be enough.” Churchill returned to his aircraft without watching the crossing. His secretary recorded what followed: twenty minutes of silence, then dictation to Eisenhower.

“General, I have received Field Marshal Montgomery’s request that General Patton be relieved for unauthorized Rhine crossing. After careful consideration, I must decline to support this request. General Patton’s operation, while uncoordinated, was successful and contributes to Allied objectives. I recommend no action be taken.” Churchill paused, then added a handwritten postscript: “Ike, keep Patton moving. We can’t match his speed—but we can’t afford to lose it.”

That evening, Churchill spoke privately with Lord Moran. The entry in Moran’s diary captured a leader stripped of illusions. “I’ve chosen American results over British pride. Monty will never forgive me. The establishment will be furious.” He poured a whiskey. “We’re no longer the leading military power in this alliance. We haven’t been for some time. I’ve been too proud to admit it.”

Asked if he regretted the decision, Churchill didn’t hesitate. “Not for a second. Pride doesn’t win wars. Speed does. Patton understands that. Monty does not. If I must choose between prestige and bringing our boys home sooner, I choose speed.” Then he laid bare the coalition’s reality. “Bernard wants Patton punished—and he’s right, by proper military standards.”

“But we are not a proper military. We are a coalition of competing national interests where the side with the most resources makes the rules. That side is no longer Britain—it is America.” Moran recorded Churchill’s next words verbatim. “I spent the war pretending we were equal partners. Today, I admitted the truth. They are the senior partner.”

“They provide the majority of men, materiel, and leadership. Patton crossed first because American doctrine has surpassed ours—not in bravery or training, but in willingness to move faster than caution recommends. That is the future of war—and we are no longer leading it.” The consequences were immediate. Montgomery never forgave him; their relationship cooled.

British chiefs of staff lodged a formal protest. Churchill’s reply was blunt. “Would you prefer I demand his relief and watch the Americans ignore me? That would undermine British authority more than quiet acceptance.” Strategically, Churchill’s refusal signaled that operational success would be rewarded—even if it violated protocol. Patton grasped it at once. “The British finally understand this is our war,” he wrote. “We’ll finish it our way.”

Years later, Churchill’s memoirs devoted a chapter to the crossings. “Patton’s Oppenheim assault proved that modern warfare rewards speed over preparation,” he wrote. “Montgomery’s Plunder was a masterpiece of planning, yet Patton achieved the same objective in a single night with a fraction of the resources. The contrast was instructive—and uncomfortable.”

In a private 1953 letter to Eisenhower, Churchill was starker. “You once asked if I regretted refusing Montgomery’s demand to fire Patton. I do not. Patton won the race to the Rhine and ended the war faster. Was he insubordinate? Absolutely. Was he necessary? More than I wished to admit.” The hardest lesson of coalition warfare is simple: sometimes you must choose between the general who makes you proud and the general who wins faster.

Churchill chose speed. He chose results. He admitted that British methods, however professional, had been surpassed by American tempo. In making that choice, he acknowledged what Britain had avoided since 1942: the empire that once defined military excellence no longer set the standard—it tried to keep pace. Montgomery wanted punishment for broken rules. Patton exposed the uncomfortable reality.

In modern warfare, the side that moves fastest wins—and Britain no longer moved fastest.

News

Patton (1970) – 20 SHOCKING Facts They Never Wanted You to Know!

– Behind the Academy Award-winning classic Patton lies a battlefield of secrets. What seemed like a straightforward war epic is…

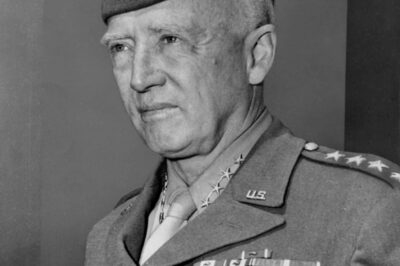

George S. Patton’s Victories Don’t Excuse What He Did

When disturbing allegations about George S. Patton surfaced, his daughter fiercely defended him. Only after her death did her writings…

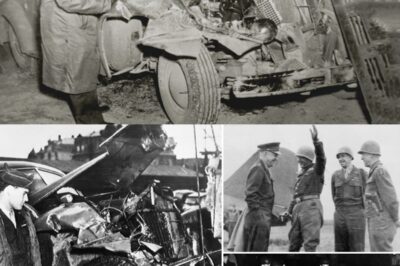

Was General Patton Silenced? The Death That Still Haunts WWII

Was General Patton MURDERED? Mystery over US war hero’s death in hospital 12 days after he was paralyzed in an…

Patton’s Assassin Confessed – He Was Paid $10,000

September 25, 1979, Washington, D.C. The Grand Ballroom of the Hilton sat in shadow—450 living ghosts at round tables under…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

June 1979, Newport Beach, California. Four days after John Wayne’s funeral, the house felt hollow—72 years of life reduced to…

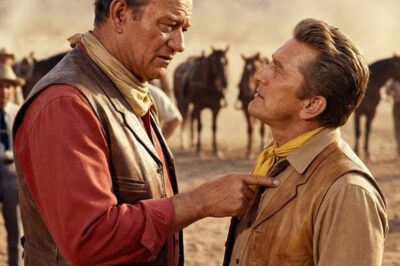

When Kirk Douglas Showed Up Late, John Wayne’s Revenge Shocked Everyone

September 1966, Durango, Mexico. Fifty crew members watched two Hollywood legends square off on a sunblasted set. Kirk Douglas had…

End of content

No more pages to load