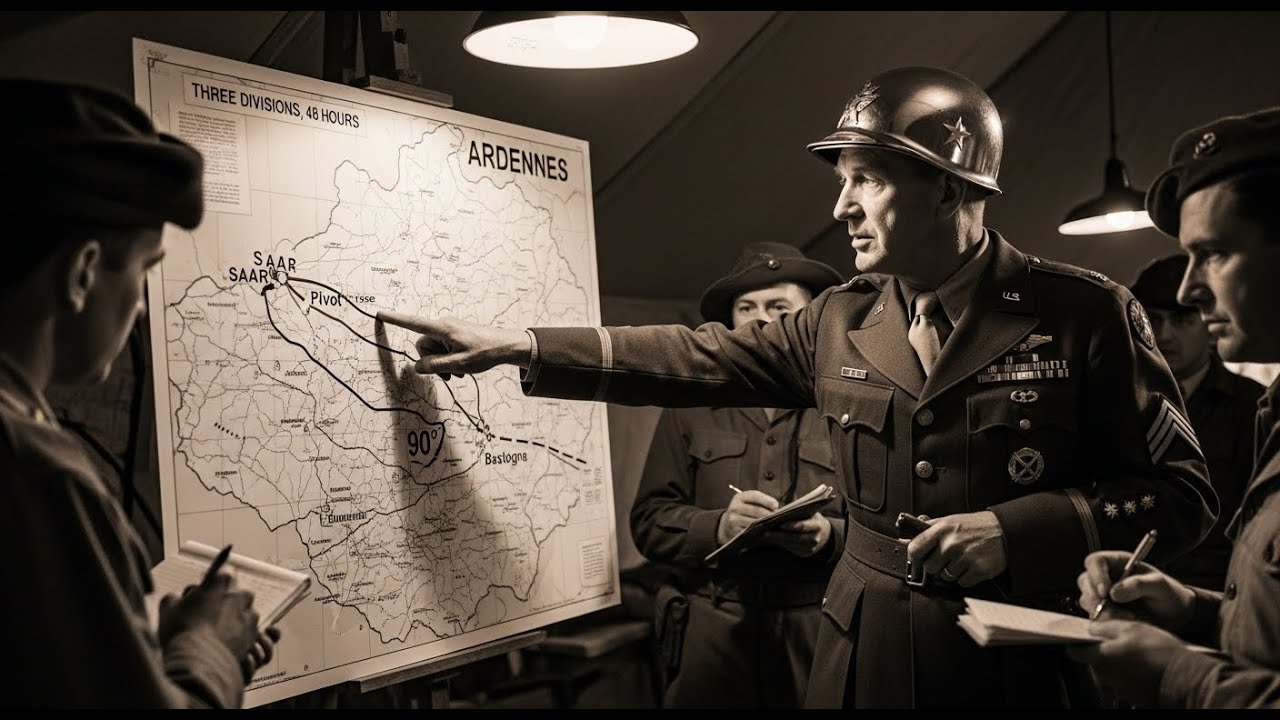

– “Impossible. Unmöglich.” That word echoed through German High Command on December 19, 1944. American General George S. Patton had announced he would disengage three full divisions from combat, pivot them 90 degrees north, march through the worst winter in decades, and attack the southern flank of the Ardennes offensive within 48 hours. German generals laughed; intelligence officers dismissed it as propaganda. Field Marshal von Rundstedt declared no army could execute such a maneuver in less than a week.

They were all wrong. Intercepted communications, diary entries, and postwar interrogations reveal how Patton’s “impossible” plan shattered German confidence and turned the Battle of the Bulge from potential victory into catastrophic defeat. Today, we reveal what German commanders actually said when Patton did the impossible. When German intelligence first intercepted messages about Third Army pivoting north, the reaction was mockery, not fear.

In Army Group B’s command bunker, Field Marshal Walter Model reviewed the report and dismissed it as Allied disinformation. “Patton is fighting in the Saar,” he told staff. “This is deception—he cannot be in two places at once.” The Ardennes offensive, codenamed Wacht am Rhein, relied on a core assumption: the Allies would need at least a week to shift forces.

German planners had studied Allied doctrine, logistics, and command structure. Moving large formations required extensive planning and supply coordination—time the Germans believed they had. A 90-degree pivot of three divisions through winter conditions? Two weeks minimum, perhaps three. Colonel General Alfred Jodl, operations chief at OKW, wrote in his diary on December 19 that Patton’s 48-hour claim was either brilliant psychological warfare or proof American commanders had lost touch with operational reality.

“No army in history has executed such a maneuver under such conditions in such time,” Jodl noted. Even Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, father of German panzer tactics, couldn’t believe it. Told of Patton’s announcement, he reportedly said, “If Patton actually accomplishes this, I will have to rewrite everything I know about armored operations.” Guderian knew armor and logistics; Patton’s promise violated bedrock principles of operational art.

German field commanders on the southern flank received orders to expect counterattacks—but not for three or four days. Forward units were told to press west, not defend south. Seventh Army, responsible for the southern shoulder, was given minimal reserves because High Command didn’t believe a major threat could materialize so fast. That disbelief was Germany’s first critical mistake.

By the time they realized Patton wasn’t bluffing, it was too late to refocus operations. December 21, 1944: German confidence began cracking. Reconnaissance units reported massive American movements heading north from the Saar—entire divisions with full equipment trains. Radio intercepts confirmed Third Army was disengaging and repositioning.

Most alarming, Luftwaffe aerial reconnaissance—despite terrible weather—spotted long columns of American vehicles rolling through the snowstorm. At Army Group B, Model’s tone changed dramatically. His chief of staff, General Hans Krebs, recorded him pacing, asking how this was possible. He demanded intelligence explain how Patton was doing in two days what should take two weeks.

German logisticians ran the numbers and concluded the Americans were attempting the impossible. Moving three divisions—about 133,000 men and 11,000 vehicles, plus tanks, artillery, ammunition, fuel, and supplies—through winter on shared roads required coordination beyond expectation. One quartermaster wrote, “Either the Americans have developed supernatural powers or our understanding of logistics is fundamentally flawed.” The psychological impact was severe.

German strategy had banked on Allied predictability and slowness. Suddenly, that assumption collapsed. “If Patton can do this,” commanders asked, “what else are the Americans capable of?” General der Panzertruppe Hasso von Manteuffel, Fifth Panzer Army commander, grasped the implications early.

He sent an urgent warning to Model: if Third Army hit the southern flank in force while German spearheads extended west, they would be isolated. “We must either accelerate to the Meuse immediately or prepare defenses to the south.” Acceleration was impossible—St. Vith and Bastogne resisted stubbornly, and fuel shortages were crippling.

The Germans had planned to seize American fuel dumps, but resistance blocked them. Panzer units ran dry while Patton supposedly marched three divisions through a blizzard. Colonel Hans von Luck later wrote, “We realized we had underestimated the enemy. The Americans we thought of as amateurs were outmaneuvering us with operational flexibility we could no longer match.”

By December 22, concern turned to alarm. Patton’s forces weren’t just moving—they were forming for attack. This wasn’t propaganda. It was real, and German High Command had no response prepared.

December 22, 1944, 6:00 a.m.: Fourth Armored Division smashed into German positions on the southern flank. The shock was immediate and total. Units told they had days to prepare were hit by full-scale American armor barely 72 hours after Patton’s announcement. Seventh Army’s command post erupted into chaos.

General der Panzertruppe Erich Brandenberger, commanding the southern shoulder, sent a frantic message to Army Group B: “Under heavy attack from American armor—multiple divisions. This is not a probe. This is a major offensive. Patton has done it.” Model’s response—recorded in command logs—showed stunned disbelief: “Confirm this is Third Army. Confirm Patton is directing the attack. How is this possible?”

When confirmation arrived, Model reportedly threw down his marshal’s baton and declared, “We are fighting a genius.” On the front lines, shock matched headquarters. Lieutenant Hans Schmidt, facing Fourth Armored, wrote, “The Americans appeared out of the snowstorm like ghosts. We were told they could not arrive for days. Yet here they were, in overwhelming strength, attacking with coordination and ferocity we had not seen before. They fought like men possessed.”

In Berlin, the atmosphere turned grim. Hitler had guaranteed the Americans couldn’t respond effectively, predicting at least ten days before any coordinated counterattack. Patton destroyed that prediction in under three. Informed of the attack, Hitler blamed intelligence and field commanders, refusing to accept that an American general had outthought and out-executed German planning.

Professional officers knew better. General der Infanterie Günther Blumentritt, Chief of Staff to von Rundstedt, wrote in his after-action report: “Patton’s relief of Bastogne represents one of the most brilliant operational achievements of the war. To disengage, move three divisions through winter, and attack within 48 hours requires staff work, logistics coordination, and command excellence exceeding anything we accomplished—even in 1940.” The southern flank began collapsing.

Units meant to advance west fought desperately to hold against Third Army. The careful timetable—already slipping—was now broken. Patton’s attack didn’t just relieve Bastogne; it shattered the operational logic of the entire offensive.

When Fourth Armored broke through to Bastogne on December 26, German High Command confronted a brutal truth. The offensive had failed—not only due to gallant resistance or fuel shortages, though both mattered. It failed because Patton had done what German planning deemed impossible. Von Rundstedt’s December 27 command conference—minutes captured after the war—revealed deep consternation.

“We built our strategy on the assumption that Allied response would be slow, disorganized, and reactive,” he began. “Patton has proven that catastrophically wrong. We are no longer fighting hesitant Allies of 1942–43. We face an enemy operating with speed and decisiveness that matches or exceeds our capabilities.” Strategic implications cascaded.

If the Americans could pivot three divisions 90 degrees in 48 hours, German operational security was meaningless. Any concentration could be met by rapid response. Surprise offensives—core to German doctrine—were obsolete against such flexibility. Panzer commanders felt the shock acutely.

General der Panzertruppe Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, diverted from the Meuse to counter Patton, wrote bitterly: “We created mobile armored warfare. We wrote the doctrine of rapid maneuver and exploitation. Now an American general uses our concepts against us—and does it better. This is a bitter pill.” At Hitler’s headquarters, the Führer demanded continuation—more resources, more determination—against operational reality.

Privately, Model, Manteuffel, and von Rundstedt acknowledged it was pointless. Patton’s relief of Bastogne showed American forces could respond faster than Germans could exploit breakthroughs. The psychological impact rippled.

German soldiers began doubting victory. They’d been told Americans were poorly led and trained. Patton shattered the myth. Troops who had fought confidently in 1940–41 now faced an enemy who could outthink, outmaneuver, and outfight them.

The Battle of the Bulge continued, but German commanders knew from December 26 onward they had lost. Patton’s 48-hour miracle didn’t just rescue a surrounded unit; it broke the back of Germany’s last major offensive and proved American capability had surpassed German expertise. After Germany’s surrender, Allied interrogations probed captured commanders.

Their reflections on Bastogne were revealing. These were professionals seeking to understand how they had been outmaneuvered. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, OKW Chief, interrogated in May 1945, admitted, “We believed our own propaganda about American incompetence. Patton destroyed that illusion. Moving an army through a blizzard and attacking within 48 hours demonstrated operational excellence we could not match in 1944. Perhaps we could in 1940; by 1944, we had lost it. Patton still had it—or the Americans had learned it.”

General der Panzertruppe Hermann Balck, among Germany’s finest tacticians, was more analytical: “Patton understood that in modern war, the side that responds faster controls tempo. He did not wait for perfect conditions or complete information. He acted decisively with what he had. That is how we won earlier. By 1944, we were cautious and slow. Patton remained aggressive and fast. That determined the outcome.”

Even Model, who fought Third Army directly, acknowledged the achievement. Before his suicide in April 1945, he told staff, “If Germany had commanders who could operate with Patton’s speed and flexibility, we would have won. Our early victories made us arrogant; we believed our doctrine superior. Patton proved doctrine matters less than execution—and his execution was flawless.” Most telling was Guderian’s postwar assessment.

He had initially vowed to rewrite armored theory if Patton succeeded. Later, he conceded, “I did not believe it possible. Logistics alone should have taken a week. Movement through winter should have been chaotic. The attack should have been piecemeal. Instead, Patton achieved near-perfect coordination. Staff work was superb. Commanders executed brilliantly. Logistics performed miracles. This was not luck—this was operational excellence at every level.”

German military historians echoed the respect. General der Infanterie Hans Speidel, Rommel’s former chief of staff, wrote: “The relief of Bastogne stands as one of the finest examples of operational art. War colleges should study not just what Patton did, but how his army executed flawlessly under impossible conditions.” The ultimate verdict came from ordinary soldiers in POW camps.

Captured German troops frequently cited Bastogne’s relief as the moment they knew Germany would lose. One former Panzer commander said, “When Patton turned his army in a blizzard and attacked within two days, we knew we were beaten—not just in that battle, but in the war. We no longer had the leadership quality or execution capability to match such an enemy.” High Command learned too late what Patton’s soldiers already knew.

“Old Blood and Guts” was more than theatrics and ivory-handled pistols. He was an operational genius who did what others deemed impossible. If this deep dive into German High Command’s stunned reaction fascinated you, subscribe now.

We’re bringing untold stories from both sides of history’s greatest conflicts—the reality behind legends, voices you’ve never heard, and perspectives that change what you thought you knew about World War II. Hit the notification bell so you never miss our next video. We have more on moments that shocked commanders, battles that changed history, and truths behind famous operations.

Drop a comment on what aspect of the Bulge you want explored next: the German view of Bastogne’s defense, the American soldiers who held the line, or the intelligence failures behind the surprise. Your suggestions drive our content. If you enjoyed this, smash the like button and share with anyone who appreciates real military history told from perspectives you won’t find in textbooks.

Thanks for watching—and remember, sometimes “the impossible” is just something nobody’s tried yet. See you next time.

News

Why Patton Was the Only General Who Predicted the German Attack

– December 9, 1944. A cold Monday morning at Third Army headquarters in Nancy, France. Colonel Oscar Koch stood before…

Patton (1970) – 20 SHOCKING Facts They Never Wanted You to Know!

– Behind the Academy Award-winning classic Patton lies a battlefield of secrets. What seemed like a straightforward war epic is…

George S. Patton’s Victories Don’t Excuse What He Did

When disturbing allegations about George S. Patton surfaced, his daughter fiercely defended him. Only after her death did her writings…

Was General Patton Silenced? The Death That Still Haunts WWII

Was General Patton MURDERED? Mystery over US war hero’s death in hospital 12 days after he was paralyzed in an…

Patton’s Assassin Confessed – He Was Paid $10,000

September 25, 1979, Washington, D.C. The Grand Ballroom of the Hilton sat in shadow—450 living ghosts at round tables under…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

June 1979, Newport Beach, California. Four days after John Wayne’s funeral, the house felt hollow—72 years of life reduced to…

End of content

No more pages to load