At 7:10 a.m. on June 4, 1942, First Lieutenant James Muri dropped to 200 feet above the Pacific, watching thirty Japanese Zeros dive from 12,000 feet toward his B-26 Marauder. He was twenty-three, on his first combat mission, with zero training for what came next. The Imperial Japanese Navy had positioned four carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, Sōryū—150 miles northwest of Midway, shielded by destroyers, battleships, and heavy cruisers. Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo commanded the most powerful strike force the Pacific had seen.

The Martin B-26 was never meant for this. Nicknamed “Widowmaker,” it carried unforgiving handling: landing speed near 150 mph, wing loading 53 lb/ft², small wings, massive engines. Pilots called it a flying coffin. Nobody imagined slinging a 2,000-pound torpedo under its belly, dropping at wavetop height through carrier flak. Nobody briefed Muri’s squadron on torpedo tactics before they scrambled at 0600.

Four B-26s took off, led by Captain James Collins. Muri flew Susie Q, named for his wife Alice. Two crews had never dropped a live torpedo; the other two had exactly one practice drop apiece. Between them: zero combat experience and ninety minutes of torpedo training. Two of the four would never return to Midway. They knew the math before takeoff.

Three hours earlier, Navy torpedo squadrons had lost forty-five aircraft out of fifty-one—two hundred twenty-five men—most within eight minutes. The B-26 carried seven: pilot, copilot, navigator, bombardier, three gunners. Muri’s copilot was Second Lieutenant Pren Moore; bombardier Second Lieutenant Russell Johnson; dorsal gunner Staff Sergeant John Gogoj; waist gunner Corporal Frank Melo; tail gunner Private Earl Ashley; navigator William Moore. They found Nagumo’s carriers at 0700—four massive flattops steaming in formation.

These were the ships that had launched Pearl Harbor six months earlier—three hundred aircraft, twelve thousand sailors. Thirty Zeros rose to meet four Marauders. The math wasn’t complicated. Collins banked hard left; tracers ripped past Susie Q’s cockpit. Muri dropped lower: 150 feet, 100, 50—propellers throwing salt spray across the windscreen. Moore called out range: 3,000 yards, 2,000, 1,500.

Akagi’s guns opened—25 mm bursts ahead, heavier shells from the destroyer screen. The sky filled with steel and smoke. Muri held course. Zeros attacked from above and behind. Gogoj’s turret hammered back, the vibration shaking the airframe. At 1,000 yards, Moore shouted release points: five seconds, four, three. Cannon hits punched the fuselage; something exploded behind the cockpit; smoke poured through the radio bay.

Moore released at 800 yards; the bomber jumped as 2,000 pounds dropped. Muri banked right to clear Akagi’s path—then every gun on the flagship locked onto Susie Q. Shells tore through wings, tail, and both engines. Muri realized he had one chance to survive the next ten seconds. He yanked left—not away from Akagi, but toward her.

The B-26 screamed across the water at 280 mph—50 feet became 40, then 30. Tracers converged from every angle. Muri aimed at the carrier’s port side—twenty feet above the waves. Akagi’s flight deck rose like a steel cliff—860 feet long, 102 feet wide—the flagship of Japan’s First Air Fleet and Nagumo’s command post. Fifteen feet. Gunners saw the bomber coming straight at them.

Some dropped flat; others kept firing. Muri held course. The bow filled his windscreen—steel, rivets, aircraft parked wingtip to wingtip. Ten feet, five, three above the Pacific—then he pulled, and Susie Q cleared Akagi’s bow by less than six feet. The B-26 thundered down the flight deck at masthead height. Sailors threw themselves flat. Crews abandoned guns. Prop wash knocked men off their feet; parked Zeros rocked on their gear.

Nagumo stood on the bridge and watched an American bomber pass twenty feet in front of him at 280 mph. The noise shattered windows; staff officers hit the deck; the admiral stayed standing. In the nose, Russell Johnson grabbed the gun and opened fire—.50-caliber rounds raked the deck bow to stern—two sailors killed, a gun position wrecked, three wounded. Shell casings scattered across Muri’s windscreen.

Behind the cockpit, Melo fought a fire in the radio bay; the waist position was shredded; hydraulic fluid sprayed everywhere. He held an extinguisher in one hand and kept firing with the other. Smoke filled the fuselage; the electrical system failed; half the instruments died. Pren Moore left his seat, crawled aft through smoke—three gunners wounded: Gogoj’s shoulder, Ashley’s leg and arm, Melo’s face lacerated. Moore pulled the first-aid kit and worked while the aircraft shook from continuous attacks.

Eight hundred sixty feet of deck flashed by in three seconds. Susie Q cleared the stern and dropped to wavetop height. Every gun on every Japanese ship tried to track the bomber—but they couldn’t shoot without hitting their own flagship. The B-26 vanished into battle smoke. Muri banked right: altitude 40 feet, airspeed 270, both engines running rough, right oil pressure dropping, left temperature climbing. Zeros swarmed behind; the turret jammed; Ashley couldn’t man the tail gun; the nose gun was dry. Susie Q had no defensive armament.

No way to fight back, no way to outrun Zeros cruising at 330 mph. The bomber was a flying wreck with seven men aboard and 150 miles of ocean to Midway. Collins appeared off Muri’s port—his B-26 looked worse—smoke from one engine, a shredded tail. Both bombers were dead meat if the Zeros pressed. Then the fighters broke off—all of them. They climbed back to their carriers.

Muri didn’t know why. At that moment, American dive bombers were approaching from 20,000 feet. He leveled at 100 feet. Airspeed 260. Fuel half tanks. Compass and altimeter alive; everything else dying. Right oil pressure dropped into red; temperature maxed; black smoke streamed. He reduced power on the right. A B-26 could fly on one engine—if it wasn’t shot full of holes and carrying wounded men and a burning radio compartment.

Moore crawled back—his flight suit covered in blood not his own—three gunners stabilized; Melo refused to stop firing. Moore slid into the copilot seat. Both men knew the math: 150 miles to Midway; fuel for maybe 200 if the tanks weren’t leaking; one engine failing; no hydraulics; no radio. They flew with Collins for twenty minutes; he fell behind—more smoke, lower altitude. Muri held speed. You can’t help a damaged aircraft by damaging your own. Collins waved; Muri waved back. Each continued alone.

Behind them, Nagumo made the decision that would lose Japan the Pacific War. The morning’s attacks convinced him Midway’s defenses were still strong. His aircraft were armed with torpedoes for ships; he ordered a changeover to bombs for the island’s airfield. Deck crews began pulling torpedoes and hauling bombs from magazines—a 90-minute process.

At 0740, a scout report arrived: American carrier spotted. The situation flipped in one transmission. Nagumo needed torpedoes again; he ordered a reversal. Deck crews scrambled, reversing the changeover—torpedoes and bombs stacked together, fuel lines everywhere—the most dangerous configuration possible. Muri knew none of this. He flew across empty ocean, watching the right engine die.

Oil pressure hit zero; temperature peaked; metal parts welded inside the R-2800. The engine could seize at any moment. Fifty miles from Midway, Moore spotted smoke—Japanese strike aircraft returning from their raid. Two dozen planes. Fighters broke away toward Susie Q. Muri pushed the left engine to maximum. The Pratt & Whitney screamed; temperature climbed past redline. The B-26 accelerated to 280 on one engine and a prayer. The Japanese fighters fell back—low on fuel, unable to chase damaged bombers all the way home.

Twenty miles out, the right engine quit. The prop windmilled; Muri feathered it. Single-engine now; altitude dropped to fifty feet. The bomber couldn’t hold height with damage and dead weight. Ten miles out, Midway’s runway appeared—6,500 feet of coral and sand—a narrow lifeline in endless ocean. For a healthy B-26, plenty. For a shot-up bomber on one engine, with no hydraulics and wounded aboard, maybe not.

Moore prepared for crash procedures. Hydraulics were gone; normal gear extension impossible. Manual extension needed two men and time they might not have. Muri lined up—and another problem: the left main tire was gone, shot away over Akagi’s deck; the rim remained. Moore had spotted it earlier. Landing on one tire and a bare rim meant a violent pull left on touchdown.

Five miles out, altitude thirty feet—single engine just keeping them airborne. Moore cranked the manual gear handle—resistance everywhere—bent linkages from battle damage. He kept cranking—forty rotations under normal conditions; today, twice that. Three miles: main gear locked. Nose wheel wouldn’t budge. He cranked harder; the handle wouldn’t turn—jammed or broken.

Landing on mains without a nose wheel meant pitching forward, props striking the runway, cartwheeling disaster. Two miles: Moore’s hands bled; Muri held twenty feet; single engine howled fifty degrees past redline—could fail any second. One mile: the nose wheel dropped and locked—Moore felt it through the mechanism. Three wheels down. One main tire missing—but three wheels down.

Muri crossed the beach at fifteen feet doing 190—too fast. Normal approach was 150 on two engines; today he needed extra speed for margin, which meant more stopping distance on a short runway patched with coral. He chopped throttle; the B-26 fell—160, 150, 140—like a brick with wings. Suzie Q hit at 135. Right main touched first; left main hit on a bare rim—sparks exploded as metal scraped coral. The aircraft pulled hard left.

Muri stomped right rudder. The nose wheel slammed down. Both props still windmilling; right prop tips shattered—metal fragments everywhere. The B-26 swerved left despite full right rudder. Muri stood on brakes—the system used the last pressure left in shot-up lines. Suzie Q slowed—100, 90, 80—the runway was running out—70, 60. Wreckage blocked the far end. Muri aimed for a gap between burning fuel and twisted metal—50, 40—and rolled to a stop with 800 feet remaining.

Fire trucks and ambulances rushed. Muri shut down the left engine; the silence was overwhelming. His hands shook on the yoke; Moore sat motionless. Three wounded gunners waited for medics. Ground crews swarmed; medics extracted the wounded. An intelligence officer appeared and asked for a report. Muri climbed out and stood on the coral, counting bullet holes—stopped at 200.

The crew chief walked the bomber with a clipboard—counting every hole, tear, and scar. Final count: 506 bullet holes. The left tire destroyed; all prop blades damaged; hydraulics wrecked; radio burned; electrics partially failed. The chief delivered his verdict: Susie Q would never fly again.

Captain Collins landed thirty minutes later—473 holes, one dead engine, tail barely attached, two wounded. Both bombers would be written off. The other two B-26s never returned. Lieutenants Herbert Mayes and William Moore took direct hits during runs; both aircraft went into the Pacific—fourteen men lost—no survivors—no wreckage. Four Marauders attacked; two returned—eight wounded, fourteen killed, zero torpedo hits. Tactically, the mission failed.

Muri sat on the runway and watched the swarm catalog damage—cannon holes, machine-gun scars, tail like Swiss cheese; both engines destroyed internally, though they ran long enough to get home. A maintenance officer asked permission to cut the name from the fuselage before scrapping. It took an hour—tin snips and careful hands—Susie Q—Alice’s nickname—came away in one piece.

A bulldozer pushed the B-26 to the beach; two days later, it was shoved into the Pacific, sinking in forty feet of water. Serial 40-1391—nine months old—one combat mission—506 holes—gone. The attack’s immediate results looked minimal—no hits, two aircraft lost. Strategically, its impact proved profound.

Nagumo watched an American bomber roar down his deck. That image burned into his mind. Midway-based aircraft were attacking in waves—B-26s with torpedoes, B-17s with bombs, Navy torpedo bombers. He decided Midway’s air defenses remained dangerous—his carriers needed to strike the airfield again—forcing the changeover to bombs. Thirty minutes later came the scout report: American carriers. He reversed—all torpedoes again.

Deck crews had already moved hundreds of bombs to hangars. Torpedoes stacked beside bombs and fuel lines—every carrier in the worst possible configuration. At 1020, SBD Dauntlesses from Enterprise arrived. Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky led them down from 14,000 feet; seventeen more followed. They had searched for two hours and found the fleet by following smoke from earlier attacks.

The Dauntlesses dove at 250 mph. Zeros were low from chasing torpedo bombers; no high cover. Akagi’s crews saw the dive bombers at 8,000 feet—too late. The first 1,000-pounder hit at 1026 near the midship elevator—penetrating the flight deck and detonating in the upper hangar—bombs stacked beside torpedoes beside fuel lines. Ten seconds later, another bomb—throwing the deck into the hangar—more ordnance, more fuel—the chain reaction began.

Akagi—Nagumo’s flagship, leader of Pearl Harbor—became a furnace. Within fifteen minutes, uncontrollable fires raged through four decks. Nagumo transferred his flag to Nagara at 1100. By nightfall, Akagi was abandoned and sinking. Kaga took four hits in six minutes and sank at 1925. Sōryū took three bombs and sank at 1913. Three carriers destroyed in six minutes of American dive bombing.

Those dive bombers found the fleet by following chaos—smoke from burning aircraft and tightened formations defending against torpedo attacks. They followed the path Muri, Collins, Mayes, and Moore had carved an hour earlier. Muri’s crew remained on Midway as the battle concluded—Japanese withdrew June 7 after losing four carriers and 248 aircraft; American losses: Yorktown and 147 aircraft—the strategic balance shifted.

The Susie Q crew received treatment—Gogoj’s shoulder surgery; Ashley’s leg and arm sutured; Melo’s face bandaged. All three stayed two weeks before evacuation. Muri wrote his report June 5; intelligence questioned him for six hours—every detail: approach altitude, Zero numbers, gun positions, the moment he chose to fly over Akagi’s deck. His hands still shook holding the pencil.

Three months later, the Distinguished Service Cross arrived—for the whole crew. The citation cited extraordinary heroism—torpedo attack under impossible conditions—flying through concentrated flak and fighters. It did not mention the miss. The Navy understood something that took years to become clear: the attack created conditions that enabled the dive bombers. No historian could prove the line from Susie Q crossing Akagi’s deck to three carriers burning ninety minutes later—but Admirals Nimitz and Spruance believed it.

Torpedo attacks forced Nagumo into pressure decisions—positioning his fleet for destruction. The B-26s and torpedo bombers died buying time and chaos; the dive bombers exploited both. Muri transferred to Eglin Field in August 1942 to train B-26 crews—teaching approach speeds, power settings, single-engine procedures, how to survive when everything fails at once. He never flew combat again. One mission was enough.

The 22nd Bomb Group continued in the Pacific, flying B-26s until transitioning to B-25s in September 1943—campaigns in New Guinea, the Philippines, Borneo—flying until Japan’s surrender. Pren Moore flew thirty-five missions over Europe in B-26s and survived; Russell Johnson flew twenty-two more before rotating home; William Moore trained navigators; Gogoj, Ashley, and Melo recovered and returned—later reassigned stateside. All seven members of Susie Q’s crew survived the war.

Muri remained in the Air Force, serving in command roles, amassing over 5,000 hours, retiring as a lieutenant colonel in 1962. He and Alice settled in Montana in 1969, on Bridger Creek near Big Timber. They lived there thirty years; Alice died in 2001; Muri stayed on the ranch. Midway became America’s most analyzed naval battle—books and documentaries dissected decisions.

Dive bomber pilots drew most attention—Wade McClusky and Richard Best became famous. Torpedo crews were remembered as tragic heroes. The B-26 attack received less attention—four Army bombers against a naval task force; two lost; zero hits; minimal tactical impact didn’t fit the victory narrative. But one detail kept drawing historians back: Nagumo on Akagi’s bridge at 0710 watching an American bomber fly past at masthead height.

Three seconds—280 mph across 860 feet of deck—that Nagumo replayed for life. Japanese culture emphasized aggressive action—attack first, attack hard, keep initiative. Nagumo built his career on those principles—Pearl Harbor embodied them. But at 0710, he saw American bombers attacking in waves. His orders from Yamamoto said keep aircraft armed with torpedoes for anti-ship operations—American carriers were the primary target.

Midway was secondary. Yet he watched torpedo tracks and high-altitude bombing—instinct said destroy Midway’s air power before it could coordinate with carriers. At 0715—five minutes after Susie Q cleared the stern—he ordered the changeover. The decision was tactical and visceral. Crews began pulling torpedoes and hauling bombs—ninety minutes under ideal conditions—these were not ideal.

The fleet was under attack; damage control fought fires; CAP coordination was chaotic. At 0740, the scout report arrived: American carriers. Nagumo faced an impossible choice: continue the Midway attack and leave his carriers vulnerable—or reverse and lose another ninety minutes. He chose reversal—torpedoes again—but hangars were already stacked with bombs; torpedoes and fuel lines turned decks into powder magazines.

At 1020, dive bombers arrived—four carriers cluttered with aircraft below, hangar bays packed with ordnance, exhausted crews, Zeros too low to intercept. Bombs that hit Akagi ignited stacked ordnance and ruptured fuel lines—fires spread through four decks within minutes—systems overwhelmed—damage catastrophic. Historians still debate causation—but none dispute the psychological impact of the B-26 attack. Nagumo saw an American bomber fly down his deck; that image influenced his decisions.

Muri never claimed his mission changed the battle. His report said the torpedo missed; the attack achieved no direct hits; two B-26s lost; the mission failed tactically. He believed that until his death in 2013. The Air Force and Navy disagreed. His Distinguished Service Cross cited extraordinary heroism. In 2003, he received the Jimmy Doolittle Award for contributions to national security through military aviation.

He accepted in Washington at eighty-four, attending with his son James Jr.; Alice had died two years earlier. He thanked his crew and the Air Force; he mentioned the fourteen men who died in the other two B-26s; he said they deserved the recognition more; then he sat down and refused to say more about Midway. Muri died February 3, 2013, in Laurel, Montana, at ninety-four, of natural causes. He was buried at the veterans cemetery in Miles City with full honors.

The metal plate with Susie Q—cut from the fuselage in June 1942—survived. He kept it for seventy-one years; his family donated it to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in 2014. It hangs in the WWII gallery—paint faded, metal spotted with rust—but the name is visible: Susie Q—Alice Moyer Muri’s nickname—she married James on Christmas Day 1941.

The wreckage of B-26 serial 40-1391 remains in forty feet of water off Eastern Island at Midway Atoll—aluminum mostly corroded, steel lasting longer, coral grown over the wings, fish sheltering in nacelles. The aircraft that flew through 506 holes and brought seven men home now serves as an artificial reef. The men understood something historians took decades to articulate: tactical failure and strategic success are not mutually exclusive.

The torpedo missed. The mission caused no direct damage. But the chaos it created contributed to decisions that destroyed three carriers ninety minutes later. No single action wins wars; moments accumulate. Muri flying over Akagi’s deck was one. Torpedo crews dying in flames were another. B-17s bombing from high altitude were a third. Each achieved little alone; together, they created victory conditions.

The math of war operates beyond individual comprehension. Muri could not know his deck run would influence an admiral. Nagumo could not know ordnance handling would prove catastrophic when dive bombers arrived. Dive crews could not know they found the fleet partly because earlier attacks tightened formations and left smoke trails. Seven men flew into combat that morning; all seven came home in a battle that killed 3,000 on both sides.

They survived because a pilot made a split-second decision under impossible pressure; because a copilot manually cranked landing gear while the aircraft shook; because three wounded gunners kept fighting; because James Muri flew home on one engine across 150 miles of ocean and landed on a shot-up runway with no hydraulics and a missing tire. The B-26 demanded perfect technique and constant attention—killing pilots for mistakes and unlucky breaks.

Its early accident rate was so high ferry crews refused to fly it; some bases grounded the fleet. But in capable hands, it performed miracles. Susie Q flew through 506 bullet holes, lost an engine, hydraulics, most electrics, and a tire—and still brought seven men home. That was not luck. That was engineering and piloting under extreme conditions.

If this story moved you, hit like. Each like helps us share these forgotten histories. Subscribe and turn on notifications—we’re rescuing stories of pilots who flew through impossible situations with nothing but skill and courage. Drop a comment—tell us where you’re watching from and if someone in your family served. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Thank you for making sure James Muri and the crew of Susie Q don’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered—and you’re helping make that happen.

News

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

– Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying German prisoners slowed at Camp Ruston as nineteen women pressed their faces against…

Japanese Kamikaze Pilots Were Shocked by America’s Proximity Fuzes

-April 6, 1945. Off Okinawa in the East China Sea, dawn breaks over Task Force 58 of the U.S. Fifth…

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home

November 2, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

Why British Carriers Terrified Japanese Pilots More Than the Mighty U.S. Fleet

April 6, 1945. A Japanese Zero screams through the morning sky at 400 mph. The pilot, Lieutenant Kenji Yamamoto, has…

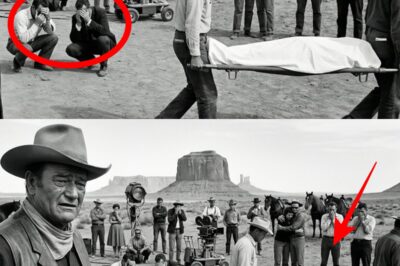

A Stuntman Died on John Wayne’s Set—What the Studio Offered His Widow Was an Insult

October 1966. A stuntman dies on John Wayne’s set. The studio’s offer to his widow is an insult. Wayne hears…

The Day John Wayne Met the Real Rooster Cogburn

March 1969. A one-eyed veteran storms onto John Wayne’s film set—furious, convinced Hollywood is mocking men like him. What happens…

End of content

No more pages to load