June 28th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas. The transport train screeched to a halt in heat so thick it felt solid. Emma Richter stood chained to three other women, wrists raw from three weeks of metal. She had crossed an ocean expecting brutality, cruelty, everything propaganda had promised about America.

Then a rancher named Jack Morrison walked toward them carrying bolt cutters. He looked at their chains with something she couldn’t identify—disgust, maybe, or anger. He spoke five words through an interpreter that made every woman freeze: “You won’t need these here.”

The chains hit the concrete floor with a sound like thunder. In that moment, everything Emma believed about her enemies shattered.

Before we dive deeper, hit subscribe and ring the notification bell. This channel reveals World War II moments textbooks forgot. Like for more untold history, and comment where you’re watching from. These stories deserve remembering.

Now, back to that scorching Texas morning. Camp Hearn sprawled across central Texas like a small city built from raw lumber and wire. Nearly 4,000 prisoners lived here by mid‑1944, most of them Afrika Korps soldiers captured in Tunisia. Veterans of Rommel’s campaigns now confined to American soil.

But one barracks held something unusual: approximately 100 German women—radio operators, Wehrmacht auxiliaries, nurses—captured across Europe. They had been gathered from various holding facilities and shipped here for what the army called “administrative efficiency.”

The women arrived expecting horror. Nazi propaganda had been explicit: Americans would torture prisoners, starve them, work them to death. The Atlantic crossing reinforced those fears—cramped conditions, minimal food, armed guards treating them like dangerous cargo.

Then came the chains. Four women linked together at the wrists. “Security protocol,” the guard said. For three weeks, Emma slept chained to Hilda on one side, Rosa on the other.

The metal wore grooves into her skin—red marks that throbbed constantly. She learned to eat with her left hand because her right was tethered. Learned to sleep sitting up when Rosa had nightmares. The chains became normal, background noise. You stopped questioning.

Then came processing day. Photographs, fingerprints, numbers assigned like inventory. They received donated civilian dresses that hung loose on their frames. American women were built differently, apparently. The dresses made them look smaller, younger, like children playing dress‑up.

Through all of this, the chains remained—until Jack Morrison arrived. He was 59 years old, weathered like old leather, wearing rancher clothes and boots caked with Texas dust. He owned 5,000 acres of pasture southwest of camp.

The war had taken his ranch hands: young men shipped overseas or pulled into defense factories. His cattle needed tending. His fences needed repair. The labor shortage was desperate across rural Texas.

Morrison stood in the administrative building looking at 12 chained women with an expression that made the camp commandant nervous. Beside him stood Wilhelm Fiser, a German‑American from Fredericksburg who would interpret. Morrison spoke. Fiser translated carefully.

“Mr. Morrison wants to know why they’re still chained.” The commandant’s answer was immediate: “Security protocol. Enemy military personnel. Potentially dangerous.”

Morrison’s response was longer, harder, delivered in a tone that left no room for negotiation. Fiser hesitated before translating. “Mr. Morrison says chains are dangerous around livestock. Could catch on equipment. Could injure workers and animals. He says he won’t take them chained. Says, ‘If they’re too dangerous to unchain, they’re too dangerous for ranch work. I’ll find other labor.’”

Silence filled the room. The commandant had heard this argument before from civilian contractors. The labor shortage gave them leverage. Morrison clearly wasn’t bluffing. The commandant made his decision. “Remove the chains.”

A guard approached with keys. The metallic click of locks opening sounded impossibly loud. The mechanism connecting Emma to Hilda released. Then Rosa, then Hannelore. The chains fell.

The sound echoed through the building like something sacred breaking. Emma stared at her wrists. The grooves remained red and angry, but the weight was gone. She lifted her arms experimentally. The freedom felt strange, terrifying almost.

Morrison stepped forward. Fiser translated his words carefully. “You’ll work hard. We’ll treat you fair. You need something, you tell the foreman. You have problems, you report them. That’s the deal.”

He paused, looked each woman directly in the eye. “And you won’t need chains here. Not on my ranch. You’re people first, prisoners second.” Fiser’s voice wavered slightly on that last part.

“People first, prisoners second.” The words hung in the Texas heat like something impossible. That night, Emma lay in her bunk, unchained for the first time in weeks. She couldn’t sleep.

Freedom felt too strange, too fragile, like something that could be revoked at dawn. She kept expecting guards to burst in, to reattach the chains, to tell them Morrison’s kindness had been a mistake.

Monday morning arrived hot and bright. Twelve German women climbed into a military truck at dawn. No chains—just two guards with rifles, who looked bored rather than alert. The truck rumbled southwest through flat landscape: endless sky, scattered cattle, barbed wire running to the horizon.

Twelve miles later, Morrison Ranch appeared. Five thousand acres of rolling pasture. Cattle dotted the distance like toys. Windmills turned slowly, pumping water from deep underground.

The main house was white clapboard with a wide porch, surrounded by ancient oaks. Barns and corrals clustered nearby, wood silvered by decades of sun. Morrison met them in the yard.

Beside him stood Tom Rawlings, his foreman—a lean man in his 50s who had worked this ranch 30 years. Several ranch hands stood nearby, older men and teenage boys. The prime‑age workers had gone to war.

Through Fiser, Morrison explained the work. Some women would tend the vegetable garden that fed the ranch household. Others would handle livestock—feeding, watering, general maintenance. Still others would repair fences, a never‑ending task on a ranch this size.

Emma was assigned to livestock work with five other women. They received work gloves—heavy leather, worn but functional. Too large for women’s hands, but serviceable.

Morrison demonstrated how to pitch hay into feeding troughs, how to pump water into metal tanks, how to move around cattle safely without startling them. Then they began.

The work was brutal. Radio operation required mental focus, but not muscle. This was different—lifting hay bales, hauling water buckets, walking miles across open pasture, checking fence lines.

By mid‑morning, Emma’s back ached. By noon, her hands were blistered despite the gloves. But she wasn’t chained. That awareness returned constantly, surprising her each time.

At noon, Morrison’s wife appeared. Sarah Morrison was practical, kind in a no‑nonsense way. She brought lunch on wooden trays: sandwiches made with thick bread and actual meat, fresh fruit, a large pitcher of lemonade beaded with condensation.

The women ate in the shade of a massive live oak. The guards sat nearby but didn’t hover. Mrs. Morrison served the food with gestures that conveyed respect. She placed plates in hands rather than dropping them on the ground. She made sure everyone had enough.

When the first pitcher emptied, she brought more without being asked. The lemonade was a revelation—cold, sweet, tart, shocking. After weeks of tepid water and bitter coffee, Emma drank slowly, trying to memorize this taste.

It felt like kindness made liquid, like proof the world still contained sweetness, even for prisoners. Rosa spoke quietly in German. “This is strange.”

Hilda asked what she meant. “All of it. The work. The food. The way they treat us. Like people.”

The afternoon brought different challenges. Tom Rawlings showed them how to repair damaged fence, how to stretch wire tight, how to hammer staples into wooden posts without splitting the wood. Tom spoke little, but his instructions were clear.

He didn’t care that they were German. Didn’t care about politics or ideology. He cared whether they worked honestly and learned quickly. By those measures, he seemed satisfied.

As the sun lowered toward the horizon, painting the sky orange and pink, the women loaded back into the truck—exhausted, sore, hands blistered, backs aching. But something had shifted.

They had worked an honest day, had been treated fairly, had drunk cold lemonade under a Texas sky. They had been called by their names instead of their numbers. The chains were gone, and the world hadn’t ended.

Three weeks into the work, Morrison had a problem. A cow had died giving birth. The calf survived—barely. Weak, old‑man legs and huge dark eyes. Without its mother, it would die within days unless someone bottle‑fed it every few hours.

Morrison walked into the barn where Emma was stacking hay bales. Fiser translated: “Mr. Morrison needs help with an orphan calf. It needs bottle feeding to survive. He’s asking for a volunteer.”

Emma’s hand went up before she’d consciously decided. Morrison nodded and gestured for her to follow. The calf lay in fresh straw, too weak to stand.

Morrison showed her how to mix the formula—powdered milk, warm water, precise measurements. How to fill the oversized bottle. How to hold it at the correct angle. How to be patient while the calf learned to suck.

“They’re stubborn at first,” Morrison said through Fiser. “But once they learn, they’ll remember you. You’ll be its mother now.”

Emma knelt in the straw. The calf smelled like hay and warmth and something indefinably alive. She touched its neck gently, then guided the bottle toward its mouth.

The calf resisted at first, turning its head, confused by this strange rubber nipple. Emma persisted, patient, murmuring soft German words she didn’t even realize she was speaking. Then the calf latched on.

It drank desperately, milk disappearing from the bottle, its tail twitching with satisfaction. Something cracked open in Emma’s chest. Not broke—opened.

She had never been maternal, never particularly liked children or animals, had never imagined herself as a caretaker. But this calf needed her. Its survival depended on her patience, her attention, her willingness to return every few hours with a bottle.

And the calf didn’t care that she was German. Didn’t care about war or uniforms or enemy status. It just knew she brought food and warmth and safety.

When the bottle emptied, the calf looked at her with eyes that held only gratitude. Morrison watched from the barn entrance. “That calf won’t forget you. You’re its person now.”

Emma nodded, not trusting her voice. She fed the calf four times a day for two weeks. Watched it grow stronger. Watched it stand on wobbly legs, then run clumsily around the corral.

Each feeding session felt like proof she could support life instead of systems designed for death. Then Morrison taught her to ride.

It happened unexpectedly. He needed to move cattle between pastures, but his regular hands were occupied elsewhere. He looked at Emma—at her competence with animals, at the way she moved around livestock without fear.

Fiser translated: “You ever ride a horse?” Emma admitted she hadn’t. “Want to learn?” She did. Desperately.

Morrison started her on an old mare named Patience—aptly named—calm and forgiving of beginner mistakes. He showed her how to mount, how to sit balanced in the saddle, how to hold the reins loosely, how to communicate through subtle shifts of weight.

The first ride was terrifying and thrilling in equal measure. The height, the movement, the power of a living creature beneath her that could choose to cooperate or rebel. But Patience was patient, and Emma was determined.

By the third lesson, she could walk the horse confidently. By the fifth, she could trot without panic. By the tenth, Morrison trusted her enough to help move small groups of cattle between pastures—real work that freed his experienced hands for harder tasks.

The transformation was remarkable. Emma Richter, radio operator from Berlin, was becoming a cowgirl in Texas. She learned the ranch’s geography—every pasture, every water source, every gate and fence line.

She learned which cattle were calm and which were difficult. Learned to read weather and cloud formations. Learned to judge time by the position of the sun instead of clocks.

Her body changed too. Muscles developed in her arms, shoulders, and legs. Her hands grew calloused, no longer soft from office work. Her skin darkened from constant sun. She became stronger than she’d ever been.

Tom Rawlings noticed. One afternoon, working together to repair a windmill, he said in his slow drawl, “You got a natural feel for this work. Most city folks never develop it.”

Emma replied in careful English. “Berlin is very different from here.” Tom nodded. “War is a strange thing. Takes people from where they belong and drops them somewhere unexpected. Sometimes they find they belong in the new place better than the old.”

Emma had no answer. But she thought about his words that night in her bunk. She thought about the calf that knew her voice, the horse that responded to her commands, the fence she’d repaired that would stand for years, the work that left her exhausted but satisfied in ways radio operation never had.

She was still a prisoner. But she was also someone capable, someone who mattered. The chains were gone from her wrists. She was beginning to feel them lift from her mind, too.

By September 1944, the work continued through summer heat into autumn. Twenty German women now worked at Morrison Ranch regularly. The program had expanded as word spread of the labor quality.

The cattle were fed. The fences stood strong. The vegetable garden produced bushels of tomatoes, beans, squash. Emma had become indispensable.

She could ride as well as any ranch hand. Could bottle‑feed calves, repair windmills, move cattle across pastures with quiet confidence. Tom Rawlings told Morrison she was the best worker he’d supervised in years—man or woman, prisoner or free.

Her English improved rapidly through daily use. She understood Tom’s drawl now, caught Morrison’s dry humor, could joke with the younger ranch hands in simple sentences that made them laugh.

The grooves on her wrists had faded completely. Only faint white lines remained where chains had marked her skin. Then the news came. Germany was losing badly. The Allies were advancing from all sides.

The war would end soon—maybe months, maybe a year. Prisoners would eventually be repatriated, sent home to whatever remained of their country. Morrison gathered all 20 German women in the barn on a Saturday afternoon in late September.

The air smelled of hay and leather. Golden light slanted through gaps in the wood. Fiser stood ready to translate. Morrison removed his hat, held it in weathered hands, and looked at each woman in turn. Then he spoke.

“You folks have worked here for months now. Good, honest work.” He nodded at Emma. “Some of you have become genuinely skilled at ranch tasks most city people never learn.” Fiser translated carefully.

Morrison continued. “When you first arrived, chained, looking scared and worn down, I wasn’t sure this would work. Wasn’t sure prisoners could be trusted without constant watching. Wasn’t sure Germans would take direction from Americans. Wasn’t sure about a lot of things.”

He paused, choosing his words. “But you proved something important. You proved that people are people, regardless of which side of a war they’re on. You proved that given decent treatment and real work, most folks respond with decent effort.”

“Chains and fear aren’t necessary. Just respect and fair dealing.” The women listened in silence. Some understood enough English now to grasp his meaning even before Fiser translated.

“The war will end. You’ll go home to Germany. What you’ll find there, I don’t know. Probably hardship, probably destruction, years of rebuilding.” His voice softened. “But remember this: you’re not prisoners first. You’re not Germans first. You’re people first.”

“People with skills and worth and dignity that no war can erase.” He looked at Emma. “You became a cowgirl in Texas. That wasn’t in any plan you made for your life, but you did it. You learned hard things, adapted, did difficult work with skill and grace.”

Fiser’s voice wavered, translating the words. The sincerity caught them off guard. Several women wiped their eyes. “When you go home,” Morrison concluded, “don’t let anyone reduce you to a category. You’re more than that. Remember it.”

Silence filled the barn. Dust floated in the warm light. A horse stamped nearby. Morrison handed each woman a gift: worn but usable work gloves and a handwritten note of thanks.

Emma’s included an extra line: “You’re welcome back if you ever want to visit. A cowgirl always has a place on this ranch.”

On May 8th, 1945, Germany surrendered. The announcement came formally through Camp Hearn. Relief, devastation, numbness—all existed at once. Emma felt oddly distant.

The war had become abstract while she worked cattle in Texas. Its end changed nothing immediately. She was still a prisoner, still on Morrison Ranch. Gradually, things shifted: repatriation schedules, paperwork, trains and ships moving millions back to shattered homelands.

Emma left in August 1945. The journey reversed her arrival, but without chains, without guards who feared her—just exhausted people returning to uncertainty. Hamburg was rubble. Berlin worse.

Her family’s building was gone. Neighbors told her what she already feared. Her parents had died in an air raid that February, buried in a mass grave. At 24, Emma was alone in a ruined city.

But she carried something with her: Texas, the ranch, the knowledge that dignity didn’t depend on nations. She worked clearing rubble, rebuilding streets. The labor was brutal, but she was strong now—calloused, resilient.

She found Hilda in a bread line. They embraced. “Do you think about Texas?” “Every day.” Years later, Jack Morrison wrote Emma back when she thanked him for removing the chains.

His reply was simple: “Decency, not generosity.” She kept the letters, the gloves, the photo labeled “Emma Richter, cowgirl.” Chains fell. Lives changed.

“You won’t need these here.”

News

They Hung My Mom On A Tree, Save Her!” The Little Girl Begged A Hell Angel — Then 99 Bikers Came

They found her running barefoot down the empty country road, her pink dress caked with mud and her voice breaking…

Bumpy Johnson’s mistress did this at his funeral… his wife grabbed her by the…

July 11th, 1968. The day the earth shook in Harlem. To the rest of the world, 1968 was already a…

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT

June 8th, 1962. 2:47 p.m., 125th Street, Harlem. May Johnson was walking out of the grocery store on Lenox Avenue…

The Woman They Paid “Almost Nothing”… Who Went On to Build 700 Buildings

San Francisco, 1872. A city of fog, timber, and risk. Gold Rush fortunes still echoed in its streets. Men built…

“Is This Pig Food?” – German Women POWs Shocked by American Corn… Until One Bite

April 1945, a muddy prison camp near Koblenz, Germany. Thirty‑four German women sat on wooden benches. Their uniforms were torn,…

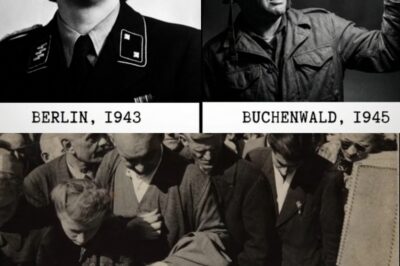

What American Soldiers Found in the Bedroom of the “Witch of Buchenwald”

April 13th, 1945. The outskirts of Weimar, Germany. A beautiful, sunny spring day. A group of American soldiers from the…

End of content

No more pages to load