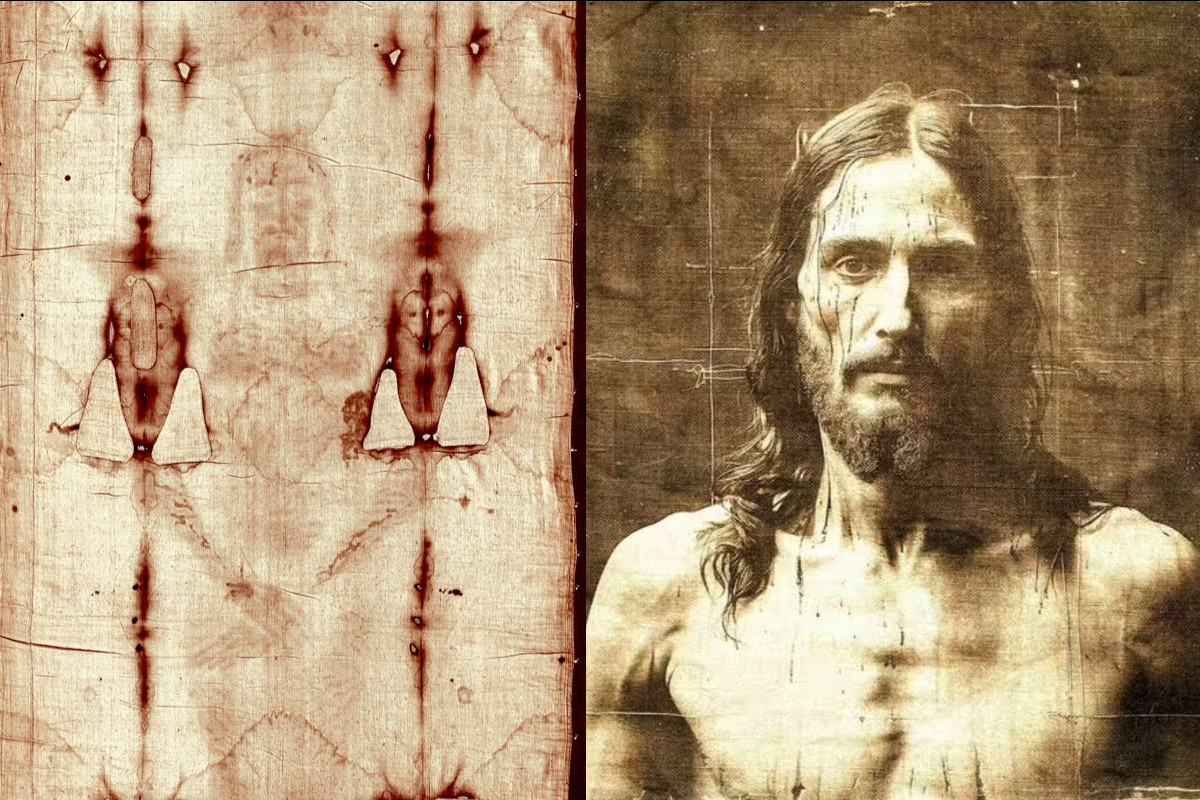

The Shroud of Turin: The Ghost in the Linen

Chapter 1: The Image That Shouldn’t Exist

In a climate-controlled server room deep beneath a European cathedral, a supercomputer hums quietly, processing millions of data points from a single object—a 14-foot strip of ancient linen. This isn’t just any artifact. It’s the Shroud of Turin, the world’s most famous religious relic, bearing a ghostly, faint image of a crucified man on both its ventral and dorsal sides.

For centuries, the narrative was simple: the Shroud was a medieval hoax, a clever painting designed to fool the masses. But the story never quite fit the facts. The image wasn’t paint, wasn’t dye, wasn’t ink. It was something else—something that, until now, defied explanation.

Now, with the rise of artificial intelligence, the Shroud’s secrets are finally being pried open. The computer stops. It catches a signal. The algorithm has identified a repeating, symmetrical pattern embedded in the linen’s chaotic fibers. This isn’t a stain—it’s a sequence. And it’s forcing physicists to ask a question they never thought they’d ask: is the Shroud actually a record of a nuclear-level event, a moment in history that physics can’t legally explain yet?

Chapter 2: The Digital Ghost

To understand why this discovery is making scientists nervous, you have to look at the details. The image on the Shroud is unbelievably superficial. It rests only on the very topmost microfibers of the linen threads—just a few hundred nanometers deep. For perspective, a human hair is about 80,000 nanometers thick. This image is thinner than a soap bubble.

The color doesn’t soak into the cloth like paint or dye. Slice a thread crosswise, and the center is white—the image sits on top like a scorch mark. There are no brush strokes, no directionality. It’s as if the fibers themselves were chemically altered by a rapid burst of energy.

When the AI looked at this, it didn’t see art. It saw data. Using principal component analysis—a technique for stripping away noise and finding core truth—the neural network revealed a field of information. The brightness and darkness of the image followed a precise, predictable rule, almost like a physical law of distance.

Imagine a cloth draped over a body. If you paint that, you use shading. But the Shroud doesn’t use shading. The AI confirmed that the intensity of the image corresponds perfectly to the distance between the cloth and the body. The closer the cloth was to the skin, the darker the image; the farther away, the lighter. It’s a perfect mathematical map.

But it gets wilder. The AI detected faint, repeating symmetries and ratios throughout the body—the distance between the eyes, the proportions of the hands, the curvature of the ribs—all obey an underlying geometric scaffolding. These patterns were invisible to the human eye for centuries, buried in the visual noise of the fabric’s weave. The AI saw them clearly.

This suggests the image wasn’t created by a human hand touching the cloth. A forger in the Middle Ages would have needed to be a master physicist, mathematician, and nanotechnologist to pull this off. They would have had to paint with invisible geometry.

Chapter 3: The Projection

The AI essentially proved that the image behaves less like a drawing and more like a projection. Scientists are now faced with a mind-bending reality: the Shroud might be a highly advanced piece of information technology created by a process we still don’t understand.

The AI didn’t solve the age debate. It made it irrelevant. Even if the cloth is from the Middle Ages, how did they encode 3D data into linen fibers? It’s like finding a QR code in a painting from the 1400s. It simply shouldn’t be there.

The Shroud is not just a picture—it’s a document containing verified data we are only now developing the tools to read.

Chapter 4: The Silence in the Background

But the AI went deeper. It analyzed the “noise” around the body. In a forgery, the background is usually empty or painted over. In the Shroud, the AI found that the background contains “data silence.” The imaging process was selective: whatever created the image only affected the cloth where the body was present, and did so with a level of collimation—meaning the energy rays were perfectly parallel, something we can only achieve today with lasers.

If you shine a flashlight on a wall, the light spreads out and gets fuzzy. The Shroud image is not fuzzy. It is razor sharp at a microscopic level. This implies that the light or energy that made the image didn’t spread out. It moved in a straight line, defying the inverse square law of physics. The AI flagged this as a physical anomaly.

So, we’re looking at a cloth that seems to have captured a moment where the laws of physics were, somehow, suspended.

Chapter 5: The Negative Miracle

Let’s rewind to 1898. A lawyer named Secondo Pia takes the first photograph of the Shroud. In his darkroom, he develops the glass plate and almost drops it. In the negative, the faint blurry image on the cloth suddenly becomes a crystal-clear positive portrait. The image on the cloth was, in effect, a photographic negative centuries before photography was invented.

How do you paint a negative when the concept doesn’t exist yet? A medieval artist paints what they see. They don’t paint the inverted light values of a face so that 500 years later, a camera can reveal the true image. That’s like writing a book in binary code in the year 1300.

Fast forward to the 1970s. A team from the Air Force Academy runs a photo of the Shroud through a VP8 image analyzer—a NASA device used to map the topography of the moon and Mars. It turns brightness into height. Put a normal photo in, and the result is a mess. But when they put the Shroud image in, it creates a perfect, undistorted 3D relief of a human form.

The scientists were stunned. The image contained accurate three-dimensional information. The darker parts were physically closer to the cloth, the lighter parts farther away. A medieval date, but with futuristic technology embedded in the cloth—a total contradiction.

Chapter 6: The Data Map

The AI didn’t just confirm the VP8 results—it refined them. The neural network stripped away the noise of the cloth weave and the burn marks from the fire of 1532. What was left was a topographic map of a human body that is anatomically flawless.

The crazy part? The data shows the body passes through the cloth. The image is consistent with a concept called volumetric projection. It’s as if the body became radiant for a split second, and that radiation passed through the linen, leaving a scorch mark that recorded the distance.

The scorch is uniform. It doesn’t penetrate the fibers—it sits on top. If an artist painted this, the paint would soak in. If a forger used a hot statue, the heat would burn through and spread sideways. But this image is precise, vertical, and incredibly high resolution. The AI analysis suggests that whatever formed this image acted in a straight line, completely ignoring gravity.

Chapter 7: The Coin and the Blood

Then the AI found something about the coins. Some researchers claimed there are faint impressions of Roman coins—specifically Pontius Pilate leptons—placed over the eyes. For years, this was debated. The AI enhanced the contrast of the orbital areas and found circular distortions matching the size and shape of these coins. If true, it dates the Shroud to around 29–36 AD. A medieval forger wouldn’t know to put rare first-century coins over the eyes, nor could they paint them so faintly they’re only visible with 21st-century computer enhancement.

The AI also analyzed the blood. It’s not paint—it’s real human blood, type AB. But here’s the weird part: the blood is still reddish. Normally, blood turns brown or black over time due to oxidation. The fact that it’s still red suggests high levels of bilirubin—a chemical produced under extreme physical stress and torture.

More importantly, the blood was on the cloth before the image was formed. The AI can see that under the blood stains, there is no image. The blood soaked in, then the flash happened. If it were a painting, the artist would have had to paint the blood first, then the negative image around the blood without overlapping. That’s technically impossible for a human hand.

Chapter 8: The Patch That Fooled the World

In 1988, science supposedly drove a stake through the heart of the mystery. Three labs—Oxford, Zurich, Arizona—used radiocarbon dating on a sample of the Shroud. The labs came back with a date: 1260–1390 AD. The headlines screamed fake. Game over.

But immediately, things got messy. The sample was cut from a single corner, the most contaminated part of the cloth—handled by thousands, exposed to smoke, candles, sweat, and patched after a fire in 1532. Nuns repaired the damaged area using invisible reweaving, a technique so skilled you can’t tell new thread from old with the naked eye.

Chemist Raymond Rogers, part of the original research team, looked at leftover threads from the 1988 sample. Under the microscope, he found the fibers from the sample corner were chemically different from the main body. The sample threads were coated with plant gum and interwoven with cotton; the main Shroud is pure linen. He also found traces of dye used to match the color. His conclusion: the labs didn’t date the Shroud—they dated a medieval repair patch.

Chapter 9: The New Science

Recently, new technology stepped in. Scientists used wide-angle X-ray scattering to inspect the structural degradation of the flax cellulose in the linen. Unlike carbon-14, this method isn’t affected by dirt or new threads. It looks at how the atoms inside the flax have broken down over time.

The results were shocking. The level of decay in the Shroud’s linen matches fabrics found in Masada, Israel, dating back to 55–74 AD. Another study used vibrational spectroscopy and came to the same conclusion—the cloth is roughly 2,000 years old.

So here’s where we stand. A disputed carbon-14 test from a contaminated corner says medieval. Multiple new advanced tests say first century. But the AI adds another layer.

Chapter 10: The Sudarium Connection

The AI cross-referenced the Shroud with another artifact—the Sudarium of Oviedo. This smaller cloth, kept in Spain, is believed to be the facecloth used to cover Jesus’s head immediately after death, before he was wrapped in the Shroud.

The Sudarium has a documented history going back to the 7th century, far before the supposed medieval forgery date of the Shroud. The AI compared the blood stains on the Sudarium with those on the Shroud. The match was perfect—the blood type is the same, the shape of the stains aligns geometrically if you place the Sudarium over the Shroud’s face.

This implies both cloths covered the same face at the same time. If the Sudarium is older than the Middle Ages, then the Shroud must be too.

Chapter 11: The Physics of a Miracle

Here’s the wild part. The AI bypassed the political mess of carbon dating and went straight to physics. And the physics are telling us this object does not behave like a painting or a rub-off. It behaves like a witness to an event.

Scientists are now looking at the Shroud not as a religious icon, but as a crime scene. The evidence left behind is pointing to a cause of the image that is theoretically impossible. If it wasn’t a painting, something turned that body into a blinding flash of light.

We’ve ruled out paint, acids, heat rubs. So what’s left? How do you create a superficial, 3D-encoded, negative image on linen without destroying the cloth?

The leading scientific explanation is vacuum ultraviolet radiation. Researchers at the ENEA agency in Italy spent years trying to replicate the Shroud’s image. They blasted linen fabrics with excimer lasers and found that a very specific type of short-wavelength ultraviolet light could color the linen in the exact same way as the Shroud. It only colors the very top layer—about 200 nanometers deep—without burning the rest.

But here’s the catch: to get that image on a human-sized cloth, you’d need a burst of radiation equivalent to 34 trillion watts of vacuum UV light. That’s more power than any searchlight on Earth. It’s comparable to a nuclear event, but without the heat—a pulse of energy shorter than 40 billionths of a second. If the pulse was any longer, the cloth would vaporize. If it was any weaker, the image wouldn’t form. It had to be perfect.

Chapter 12: The Collapse State Theory

Some physicists have proposed the collapsed state theory: the body underwent a process where its mass was converted directly into energy. Einstein’s famous equation E=mc² tells us that a small amount of mass contains a huge amount of energy. If the atoms in a human body were to suddenly decay or transform, it would release a flash of radiation.

The AI detected that the image is orthographic. The radiation moved in a perfectly straight line up and down, perpendicular to gravity. It didn’t radiate out in a sphere. This suggests a controlled event—like an event horizon, the point of no return around a black hole, but instead of gravity, this was an event horizon of biology. The body reached a critical state and phase-shifted.

Chapter 13: The Plasma Discharge Theory

Another theory gaining traction is the corona discharge theory. This involves a massive electrostatic discharge—imagine the body becoming charged with millions of volts of electricity, creating a plasma discharge that scorched the linen. The AI found patterns consistent with high-voltage fractal discharges known as Lichtenberg figures, often found after lightning strikes.

Chapter 14: The Fourth Dimension

But the most mind-bending theory is the fourth-dimensional hypothesis. Some theoretical physicists have looked at the AI’s 3D mapping and suggested that the image looks like a 3D object being pushed through a 2D plane. If a three-dimensional object passes through a two-dimensional world, it leaves a cross-section. But if a body were to move into a higher dimension, the energy release might leave a shadow on our three-dimensional world, which on a 2D cloth looks like the Shroud image.

It sounds like science fiction, but the Shroud is the only object on Earth that possesses these properties.

Chapter 15: The Vanishing

The AI found absolutely no signs of putrefaction. Usually, a body begins to decompose after 40 hours, releasing liquid and ammonia that would destroy the image and rot the cloth. The Shroud shows no signs of this. This means the body was there long enough to form the blood stains and rigor mortis, but vanished before decomposition could start.

The body didn’t get up and walk away. If it had, the blood stains would be smeared. The AI analysis shows the blood stains are pristine. The fibers of the cloth are not broken or dragged. This implies the body disappeared from inside the cloth without disturbing the fabric. It effectively passed through the linen—mechanically transparent matter.

Chapter 16: The Ultimate Question

So if this is a medieval fake, the forger had access to technology that exceeds 21st-century science. They needed a UV laser array, a particle accelerator, and a knowledge of quantum mechanics. And if it’s not a fake, well, then we are looking at the physical residue of a singularity.

The AI didn’t find a brush stroke. It found the signature of a flash—a flash that lasted a fraction of a second but left a mark that has survived for 2,000 years.

Epilogue: The Ghost in the Linen

The Shroud of Turin remains the world’s most enigmatic artifact. Is it proof of a supernatural event? Or is it the most elaborate, genius prank in human history that we still can’t figure out? What if we are just scratching the surface of physics we haven’t discovered yet?

The AI has shown us that the Shroud is not just a picture—it’s a document, a witness, a map to a moment when the laws of physics might have bent, if only for an instant. And whether you see a miracle, a mystery, or a message from the edge of science, one thing is certain: the Shroud is calling us to look deeper, to question harder, and to wonder at the ghost in the linen.

News

Muhammad Ali Walked Into a “WHITES ONLY” Diner in 1974—What He Did Next Changed Owner’s Life FOREVER

In the summer of 1974, just months after reclaiming his heavyweight title in the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle,” Muhammad…

Dean Martin found his oldest friend ruined — what he did next sh0cked Hollywood

Hollywood, CA — On a gray Tuesday morning in November 1975, the doorbell at Jerry Lewis’s mansion rang with the…

Dean Martin’s WWII secret he hid for 30 years – what he revealed SH0CKED everyone

Las Vegas, NV — On December 7, 1975, the Sands Hotel showroom was packed with 1,200 guests eager to see…

Princess Diana’s Surgeon Breaks His Silence After Decades – The Truth Is Sh0cking!

Princess Diana’s Final Hours: The Surgeon’s Story That Shatters Decades of Silence For more than twenty-five years, the story of…

30+ Women Found in a Secret Tunnel Under Hulk Hogan’s Mansion — And It Changes Everything!

Hulk Hogan’s Hidden Tunnel: The Shocking Story That Changed Celebrity Legacy Forever When federal agents arrived at the waterfront mansion…

German General Escaped Capture — 80 Years Later, His Safehouse Was Found Hidden Behind a False Wall

The Hidden Room: How Time Unmasked a Ghost of the Third Reich It was supposed to be a mundane job—a…

End of content

No more pages to load