In the spring of 1979, Hollywood’s toughest cowboy was fighting his final battle. John Wayne, the man who had defined American masculinity for generations, was dying. Cancer had stripped the weight from his 6’4” frame, leaving him gaunt and barely recognizable at just 140 pounds. The Duke, now 72, was no longer the swaggering giant who once filled the screen—he was a shadow of himself, and everyone around him knew it.

Yet, the cruelest blow wasn’t the disease. It was the pity. Friends, family, and fans spoke to Wayne in gentle, mournful tones, their eyes filled with sadness. They treated him as if he were already gone, and for Wayne, that quiet grief cut deeper than any diagnosis. He wanted dignity, not sympathy. He wanted to be Duke, not a patient.

Then Dean Martin came to visit.

A Friendship Forged in Hollywood’s Golden Era

The story of Dean Martin’s final visit to John Wayne is more than a tale of two legends—it’s a lesson in friendship, compassion, and what it truly means to honor someone’s spirit.

Wayne and Martin first met in 1959 on the set of “Rio Bravo.” Duke was already Hollywood royalty; Dean was making the leap from Rat Pack crooner and comedian to serious actor. Director Howard Hawks had cast Martin as Dude, a troubled deputy fighting for redemption—a role that demanded vulnerability and grit. Wayne was skeptical at first, but Martin’s performance won him over. More importantly, it sparked a genuine friendship, rare in an industry of fleeting alliances.

They worked together again in 1970 on “The Undefeated,” and their bond deepened. It wasn’t a friendship of daily calls or public displays. It was real—built on respect, humor, and an understanding that transcended Hollywood’s glitz.

The Final Act: Wayne’s Battle and Martin’s Visit

By 1979, both men had weathered personal storms. Wayne’s cancer had returned, this time to his stomach. Surgery left him frail, his legendary presence reduced to slow, careful movements. Still, the Duke refused to quit. He made public appearances, determined to show the world he was still fighting.

On April 9, 1979, Wayne appeared at the Academy Awards to present Best Picture. The audience gasped at his frail appearance; some wept openly. The standing ovation was not just for the award—it was for a dying man’s courage. Backstage, Wayne was swarmed by well-wishers offering praise and sympathy. He thanked them, but inside, he felt the weight of being mourned while still alive.

A few weeks later, Dean Martin called. Unlike others, Dean didn’t ask about Wayne’s health or offer condolences. He simply said, “Duke, I’m coming by tomorrow. Make sure you’re home and not dying or anything inconvenient like that.” Wayne laughed—a sound his daughter, Isa, hadn’t heard in weeks.

The next day, Martin arrived at Wayne’s Newport Beach home. Isa greeted him with caution, worried the visit would drain her father. But Martin brushed past her, found Wayne in his oversized robe, and delivered the line that would become legendary: “Jesus, Duke, you look like hell. What happened? You stop eating beef?”

Wayne stared at his friend. Then he laughed—a deep, genuine laugh that filled the room. For the next two hours, Martin did what no one else dared: he treated Wayne like Duke. No talk of cancer, no sorrow, no goodbyes. Just stories, jokes, and banter about Hollywood, old directors, and bad singers in Vegas. They argued, they teased, they laughed until Wayne coughed, and Martin finished his joke with the wrong punchline, prompting more laughter.

Isa watched from the doorway, later recalling, “I saw my father laugh more in those two hours with Dean than he had in the previous two months.” Martin didn’t coddle Wayne; he didn’t treat him like a patient. He was simply Dean—the same irreverent friend Wayne had known for decades.

A Moment That Transcended Farewells

As Martin stood to leave, there was a brief pause—a silent acknowledgment of everything unsaid. He could have offered a heartfelt goodbye, expressed gratitude, or shared his sorrow. But Martin understood that Wayne didn’t need closure; he needed dignity. So instead, he joked, “Try to eat something, would you? You’re making the rest of us look fat.” Wayne grinned, “Get out of here before I throw something at you.”

Martin left, never to see Wayne alive again. Two months later, on June 11, 1979, John Wayne died. At his funeral, Martin was one of the pallbearers, standing alongside Frank Sinatra, James Stewart, and other giants of Hollywood.

Asked later if he regretted not saying goodbye, Martin replied, “No. Duke knew how I felt. We didn’t need to say the words. What he needed from me was to be his friend, not his mourner.”

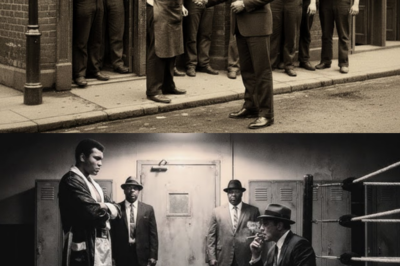

![Dean Martin and John Wayne [Two of my favorites.]](https://i.pinimg.com/736x/b7/7a/4e/b77a4e43a1d960f88d78620954db6c77.jpg)

The Legacy: Dignity, Not Pity

Years later, Wayne’s daughter Isa wrote about Martin’s visit in her memoir: “Dean gave my father something more valuable than any goodbye. He gave him his dignity. He gave him normalcy. He gave him two hours of feeling alive instead of feeling like he was already dead.”

Dean Martin’s philosophy, echoed by his own daughter Deanna after his death in 1995, was simple: “When someone is dying, the kindest thing you can do is not make them feel like they’re dying. Treat them like they’re still the person they’ve always been, because that’s who they want to be.”

This story is not just about the end of an era. It’s about the power of seeing past illness to the person underneath. It’s about friendship that honors, uplifts, and restores dignity when it matters most.

For two hours in 1979, John Wayne wasn’t a dying man. He was Duke—still tough, still ornery, still laughing. And the man who gave him that gift was Dean Martin.

What We Can Learn

In a world where pity often overshadows compassion, Martin’s visit reminds us that the greatest kindness is treating people as themselves, not as their illness. It’s a lesson in love, dignity, and humanity—one that outlasts even the toughest battles.

Share your thoughts below, and reflect on the friendships that have shaped your life. Sometimes, the greatest gift is simply being there—exactly as you always have, even when everything else has changed.

News

Muhammad Ali Walked Into a “WHITES ONLY” Diner in 1974—What He Did Next Changed Owner’s Life FOREVER

In the summer of 1974, just months after reclaiming his heavyweight title in the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle,” Muhammad…

Dean Martin found his oldest friend ruined — what he did next sh0cked Hollywood

Hollywood, CA — On a gray Tuesday morning in November 1975, the doorbell at Jerry Lewis’s mansion rang with the…

Dean Martin’s WWII secret he hid for 30 years – what he revealed SH0CKED everyone

Las Vegas, NV — On December 7, 1975, the Sands Hotel showroom was packed with 1,200 guests eager to see…

Princess Diana’s Surgeon Breaks His Silence After Decades – The Truth Is Sh0cking!

Princess Diana’s Final Hours: The Surgeon’s Story That Shatters Decades of Silence For more than twenty-five years, the story of…

30+ Women Found in a Secret Tunnel Under Hulk Hogan’s Mansion — And It Changes Everything!

Hulk Hogan’s Hidden Tunnel: The Shocking Story That Changed Celebrity Legacy Forever When federal agents arrived at the waterfront mansion…

German General Escaped Capture — 80 Years Later, His Safehouse Was Found Hidden Behind a False Wall

The Hidden Room: How Time Unmasked a Ghost of the Third Reich It was supposed to be a mundane job—a…

End of content

No more pages to load